Photos by Ralph Naranjo

It took some time for the Stuart Knockabout, an L. Francis Herreshoff design, to take root and finally flourish. The 28-foot day boat first appeared in 1932 as line drawing number 53 in the L. Francis annals, and only one boat was built. In 1933, Ben My Chree (a Galic term of endearment), was launched and wound up nestled away in Casco Bay, Maine, at the island home of owner Willoughby Stuart. With its own small marine railway and boat shed, Ben My Chree remained in the family for nearly 40 years. In the mid-1980s, it was discovered in a Massachusetts boat shed by Bill Harding, a sailor known for his deft hand on the tiller and the builder of the popular Herreshoff 12 replica-affectionately known as the Doughdish. Harding fell for the lines of daysailer he had discovered, and he researched the boats lineage. After getting a feel for what it had to offer under sail, he decided that this was another slice of sailing history that deserved being resurrected.

Harding built molds and used his already proven approach to turning a timber Herreshoff into a fiberglass favorite. To accomplish the goal, he once again went to boat builders Edey and Duff to do the hull and deck laminating and Ballentines Boat Shop to harness its carpentry skills and talents in finishing off these elegantly trimmed knockabouts. Today, Ballentines handles all the manufacturing and marketing, and even puts on the annual national championship. There are more than 80 boats sailing in the wake of Ben My Chree, and the reason for their success centers around how the boat was originally designed, where it is built today, and why it will continue to sail into the future.

While nearly every major New England boatbuilder is offering a contemporary classic daysailer today (see PS January 2009 online), the Knockabouts long production run and coast-to-coast following give it an investment appeal that you seldom see in the world of sailboats-of any size. For a retired cruiser looking to downsize to a daysailer, this reason alone should bump the Stuart Knockabout up into the final round of hulls under consideration.

What makes this boat such a pleasure to sail has as much to do with whats missing as whats included. This sloop has been stripped to its essence, not a parsimonious approach to boat building, but rather one in which a fine pedigree is created from the foot of the keel to the top of the mast. There is also a startling difference between most contemporary, 28-foot production sailboats and the Stuart Knockabout. The latest luxury daysailers are accessorized with a cabin, bunks, galley stove, a small diesel-plus tanks to fill with water and fuel. While daysailing, the engine coaxes the boat on and off the mooring, and all too often, is a substitute for light-air sails. But for many, the bunks go unused and the stove remains cold for months at a time. The tanks grow their own plankton. In the end, the owners are lugging around a lot of unnecessary structure that shrinks the cockpit, lowers the waterline, raises the center of gravity and kicks up the cost along with the annual maintenance invoices. In short, more boat isn’t necessarily more fun.

The design

The L. Francis Herreshoff design No. 53 defines a shoal draft, 28-foot centerboard/sloop. It has shallow draft (2 feet, 9 inches centerboard up and 5 feet, 6 inches centerboard down), sporting an impressive 50-percent ballast ratio that recoups the righting moment trade-off in the commitment to shallow draft and a lean (6-foot, 11-inch) beam hull. This results in good sail-carrying ability, and is why the Stuart Knockabout, like many of Herreshoffs designs, can make the most of long waterlines, a classic modified spoon bow, and fine sections aft. The net result is a 22-foot, 10-inch resting waterline that grows considerably with just a small amount of heel or squat, and an easily driven hull that can cope with breeze and chop, despite its low freeboard.

The Marconi mainsail and small clubfooted jib yield a combined 265 square feet of working sail area. This is fairly small by Herreshoffs (and todays) standards, but its clean hull lines provide adequate light-air efficiency, especially with the genoa substituted for the self-tacking working jib. An asymmetric spinnaker rounds out the light-air inventory, and even with the relatively low-aspect rig and moderate amount of sail area, the sloop starts moving with little more than a zephyr and is a delight to sail throughout a wide wind range. A J/80 crew will wave as they go by, but after a couple of hours, those lads leaning against the lifelines will envy the knockabout crew sitting in the cockpit snacking or sharing a tasty lunch.

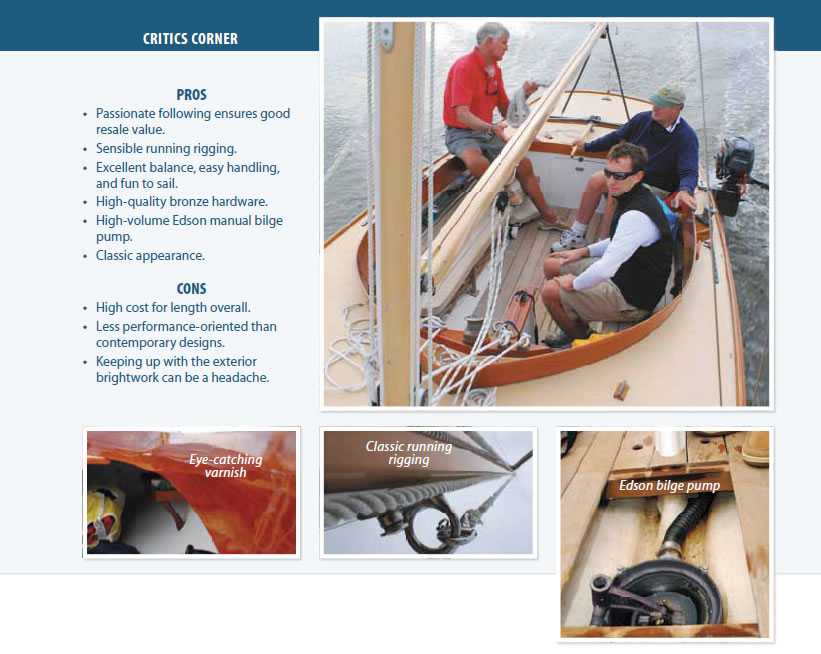

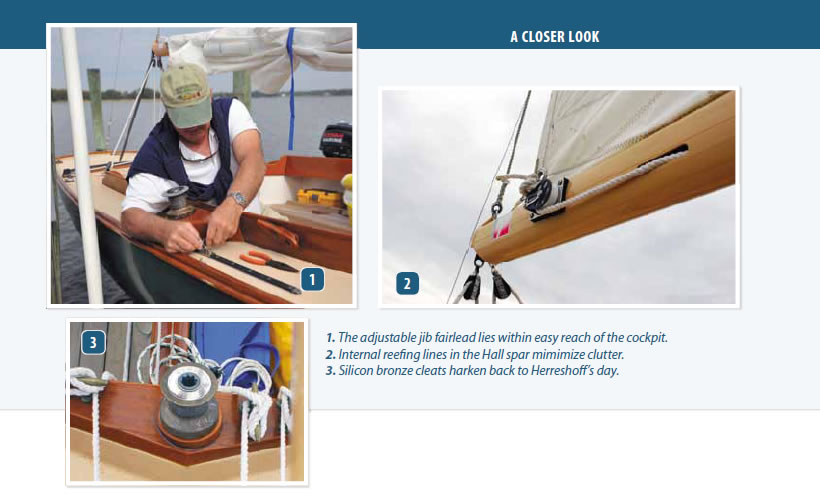

The boats a made-in-America tale of Yankee tradition. Today, Hall Spars does the rig, and its just the right combination of alloy spar, low-maintenance reliability, and a buff-color traditional finish that conveys aesthetics and good performance. Even the sensibility of traditional three-strand, easy to splice, running rigging fits the equation. Edson casts the traditional bronze hardware, and provides the pump thats set deep in the bilge.

With a rail-to-rail traveler on the aft deck and a mainsail vang, theres plenty of opportunity to optimize mainsail shape and trim. The ballast-derived righting moment and moderate sail area keep the crew from scrambling to the rail as the breeze builds. One of the many appealing design attributes found in this boat is the way sailing remains civilized-an in-the-cockpit experience rather than a hang-over-the-rail tribulation. Even when the breeze pipes up, the moderate sail area and high ballast ratio locks in a welcome stiffness, and it justifies lugging around 2,400 pounds of lead ballast in a 4,000-pound boat. The modern foam/fiberglass sandwich hulls and decks weigh less than the original hulls and the ballast has been upped a bit adding extra stiffness.

The proclivity to heel is the Achilles heel of boats built with non-self-bailing cockpits. In this case, the Stuarts high coamings combine with its stiff countenance to prevent the down-flooding linked to a deep knockdown, a very unlikely occurrence. The crew at Ballentines add buoyancy (foam aft and a water-tight bulkhead in the stem) to keep a swamped hull on the surface. According to well-kept Ballentine records, one boat was actually caught in the vortex of a tornado moving over a lake with winds well over 100 knots. The boat was knocked down and swamped, but the owners were surprised at how well the built-in flotation kept it on the surface and upright, despite the flooded hull.

Under sail

The Stuart Knockabout is a sailboat that looks as good underway as it feels at the helm. A long, carefully sculpted, varnished locust tiller delivers a fingertip feel. Observers note that even with the slightest bit of heel, the well-proportioned sloop stretches its waterline just enough to settle into the seaway and shoulder the waves without excess pitching. The long tiller affords enough leverage to eliminate any barn-door effect from the low-aspect-ratio attached rudder. The long run of keel and forefoot cutaway are in harmony with the sail plan. This results in on-the-wind sailing that could be described as balanced, and off-the-wind sailing that is a nicely controlled endeavor.

The large-main/small-jib sail plan is in complete harmony with the underbody. As the breeze increases, the Knockabout heels gradually and remains reluctant to go much beyond 15 to 20 degrees. Naturally, big increases in wind velocity, such as during a thunderstorm, can result in being overpowered. Like any sailboat, its not immune to fire drills.

Under power

The Stuart Knockabout is a prime candidate for an electric Torqueedo outboard or a small 3- or 4-horsepower, long-shaft four-stroke outboard. A port mounting bracket is fitted near the tiller, and the low freeboard gives the outboard plenty of prop submersion. When the engine is not in use, its easy to haul it back aboard, remove the bracket and stow the motor and bracket under the foredeck.

Comparison

Pocket cruisers are indeed one of the most worthy ways to voyage under sail. But if your stints on the water are measured in hours not days, weeks, or months, why lug along a cabin and all that goes into such an interior? Look around your marina or out at the moored fleets, and tally up how often you see folks perched uncomfortably atop the cabin houses because the cockpit is nearly nonexistent. Add up how many of the capable cruisers return home to their slips in the late afternoon rather than swing-on-the-hook in a quiet cove. Designers and builders have been noting this trend, and the result has been a resurgence in capable sailing, large cockpit, daysailers. But rather than shell out $80,000 (or much more) for one of these new iterations, an option is to track down an old Stuart Knockabout. The Knockabout has both the enduring appeal of a classic and the design advantages of a true daysailer. It is a sailboat that has indeed had multi-generational appeal.

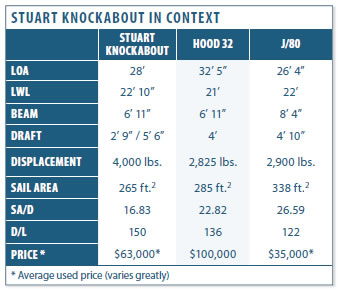

In the just under and just over 30-foot size boat, youll find cruisers, racers, and everything in between. Its this tween range that got us going this month and led to our close scrutiny of the Stuart Knockabout. The boat is neither a cruiser, nor a racer for the adrenalin-dripping sailor hoping to keep up with the kiteboarders. The Stuart works for those looking to savor a couple of hours of an afternoon sea breeze or a bit of local club racing. How she compares with a couple of other boats we call daysailers is worth mentioning. (See In Context table on right.)

The new CW Hood 32 is an elegant, and technically tricked-out, long-ended daysailer. With a carbon rig and vacuum-bagged molded hull, it has a few feet on the Stuart and still comes in lighter in displacement. Its Performance Handicap Racing Fleet (PHRF) rating of 147 will appeal to the race-oriented, as will the carbon spar and rod rigging.

The out-of-production J/80 is more of a one-design racer than leisure daysailer, and its proven ability under sail has a lasting legacy. Over 1,300 boats have been launched, and the used price for a sound boat is about $35,000. The new J/Boats that bracket the J/80 are the smaller, 22-foot J/70 speedster ($50,000) and the 29-foot, auxilliary-diesel powered J/88 ($150,000). Both are fine boats, but they offer less than an apples to apples correlation with the Stuart Knockabout.

Conclusion

The bottom line, at least from our perspective, is that although sailboat design and technological advances have moved ahead, and made for performance enhancements that count on the race course, the delight of simply being underway in a tried and proven traditional design still has merit.

Theres a lot to appreciate about a boat thats easy to handle, leaves just a few ripples in her wake, and is as pleasant to look at as she is to sail.

The Stuart Knockabouts performance ratios mark it as more conservative than contemporary daysailors.