We were somewhat appalled by the virtual elimination of boats under 40 feet from the U.S. Sailboat Show in Annapolis, MD last fall. We don’t have a problem with big boats; sailors live aboard, cruise far, and the charter market needs vessels. However, it is clear that this trend toward bigger boats can have a negative impact on small boat owners. The emphasis on larger boats means many of the problems facing small boat owners fade from view—most notably, the storage problem.

For the average sailor, it seems there is always something that just won’t fit in a locker—an inflatable kayak, gas cans we don’t want below, or sails that ought to be in a sail locker if the designer hadn’t reasoned that sail lockers are less important than a quarter berth now that the roller furling jib is standard.

The first rule for small boat sailors is that less is more. Every year about 3,000 hikers attempt the 2,100-mile Appalachian trail with only what they can carry on their backs and resupplies of food every 5-10 days. Unless you are bound around the world, you simply don’t need tons of gear and all the comforts of home. They won’t add comfort if they are in the way, and overloading a boat harms safety and performance. If you can’t live without all that stuff, get a bigger boat or learn to sail with less.

Even if you pare down your belongings, there are still many stowage conundrums to solve, but solve them we will. Every boat is different, so no solution is universal. However, the following approaches have worked for me over the years, and may suggest a solution to your unique storage challenge.

DINGHY ON THE BOW

Davits are a godsend if you can fit them. I’ve cruised with and without, and with is much better. You can tow the dinghy, but you’ll lose a fraction of a knot. In boisterous (good sailing) weather, you constantly look over your shoulder to confirm its still there. In rough weather it has to come aboard. Loading the dinghy in the bow is a pain, often reducing its use. The engine has to come off, and if it’s an inflatable dinghy, it needs an engine because it will row very poorly.

A dinghy mounted on foredeck will cause the boat to yaw more at anchor (see “Yawing and Anchor Holding,” PS February 2020). The dinghy may also block the bow hatch, reducing ventilation and cutting off a potential fire escape.

The solutions are mostly compromises. Smaller dinghies, ones that inflate, or dinghy-alternatives, like kayaks. Our suggestion is to look at the available storage space before you start thinking about what you need. Picking a the dinghy first is a recipe for disaster. Whether you do or don’t have davits, you will want to closely consider how big a dinghy you need, and where you will put it.

COCKPIT SPAGHETTI

The trend is for all controls to be led to the cockpit, although we’re not completely sold on this. This can mean the cockpit is now home to multiple halyards, multiple sheets, barberhaulers, outhaulers, reefing lines, furler lines, vang tails, and any other running rigging the boat may have. On our simple F-24 we would have 17 lines to be led to the cockpit. This would be more if the main outhaul, downhaul, and reefing lines were not rigged on the boom.

Because the F-24 is a trimaran, some of the tails can be left on the wing decks. Less frequently used lines are coiled and stored near the mast base. Some are thrown down the companionway, traditional on many race boats. A few are coiled in figure-8s and hung from cleats or hooks. But the best cruiser solution is often sheet bags, where they can be flaked, tangle- and twist-free (see “Stopping Mainsheet Twist – Pt. 2,” PS June 2022).

Traditional locations are on either side of the companionway and at either end of the cockpit seating benches. There can be a separate pocket for each line (best for frequently used lines), or they can share a larger space (more versatile for lines you don’t use every day). Excess Catamarans have a row of wells for the ropes to drop in, just inches away from the winches.

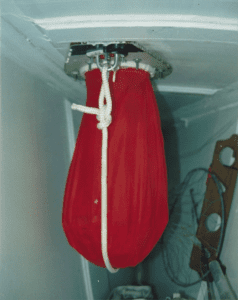

HATCH BAGS

Sometimes called cat-bags because they were common on beach cats, this is a fabric or mesh bag that hangs from a special lip inside 6-inch screw-in access ports. The length and diameter can vary. We’ve used them for mooring bridles and spare rodes. They nearly always leak a little, so locate them where a few drips won’t matter. We made the mistake of placing one over a bunk. On the other hand, the bags have the advantage of being well-ventilated, particularly if the bag is mesh.

BOAT HOOKS

Most people think of boat hooks as tools, not cargo, but you’ve got to stow them somewhere. And it helps if they are handy. I like non-collapsing boat hooks stored on deck; they are not ruined when slightly bent and you can reliably push, something you can never fully rely upon with a telescoping hook. Pick a place where they won’t snag lines. I prefer ties over clips, which loosen over time. I assume this tendency for clips to expand is the reason be why I find so many boat hooks on the beach.

RUNT STEPS

The step from the deck down into the cockpit is often too far for bad knees. A short helmsman may want a stool or an extra step. This extra step or stool can make a great place to stow things needed on deck— sunscreen, work gloves for raising anchor, or winch covers. Anything small that is frequently used and can get wet.

BUILT-IN DRAWERS

I’ve long been fascinated by some of the built-in tackle box ideas that offshore fisherman come up with, but have never found the right application and some are frightfully expensive. Some built-in tackle boxes retail for more than $800 (www.boatoutfitters.com/storage). We believe a talented DIY could certainly figure out a simple way to slide an inexpensive Plano tackle box into a molded hatch. We’ll leave this to the carpenters.

CABIN-TOP BAGS

We’ve seen these on a few cruisers and used them on auto trips. There are many choices for $100-200 that could swallow up ropes and sails. Although we’ve tested water-tight bags, we’ve not tested this iteration.

The drawback is that you’ll need a hard point—possibly one you install yourself— to lash it down. For many, the idea of drilling a hole and compromising the deck is intimidating. As we demonstrated in the June 2022 issue, it need not be (see “A Solid Connection, PS June 2022).

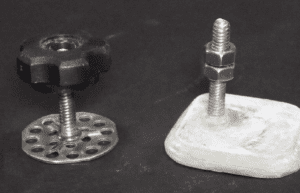

If you still don’t want to mess with drilling and filling, use glue-on mounts. Not the light-duty self-adhesive sort they sell in the grocery store for holding a towel or a picture, but the heavy duty sort that are permanently affixed with epoxy or Plexus. We’ve used these to mount air conditioners, solar panels, electrical panels, and even to secure anchors.

These glue-on mounts are as strong as a small padeye and there is zero chance of leaks. The fitting can be a stud, a loop of Dyneema, or a stainless padeye if that is what you want (see “Glue-On Fasteners,” PS July 2017).

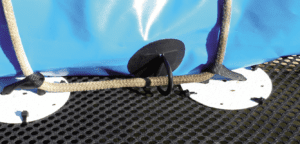

Hard points can be sewn to tramps, as is commonly done for hiking straps. Or you can make a temporary attachment point that is quite secure by lacing a fiberglass disk to the tramp fabric with 550 cord or cable ties. It’s as strong as the fabric and will spread the force over an area as large as the disk you chose. For securing our sail dry bag (see, “Dry Bags Provide a Secure Spot for Sails”), and coastal sailing, you can use 5/64-inch fiberglass shower surround.

JERRY CANS

The built-in fuel tank should suit most of your purposes, but occasionally you’ll need more capacity. Storing flammables on deck—though not an imperative—reduces the risk of hazardous cabin spills. As for water, if you are getting it from spigots on shore, your jugs might as well be kept on deck, where they are convenient.

We’re not big fans of lashing jerry jugs to stanchions at sea. We seldom did, because they can damage stanchions and encourage stanchion base leaks. Realistically, offshore sailors should have a plan to bring the cans below in foul weather and secure them.

The US Coast Guard does not expressly prohibit the storage of gasoline below decks. The cans must meet UL requirements, be completely free of leaks, and be well secured. Not in a machinery compartment, of course. We see a lot of cans in cockpit lockers, which gives us the heebie geebies, because these lockers typically drain to the bilge and junk is often piled deep.

The simple solution is to seal the locker off from the rest of the boat and vent it to a safe place, either overboard or into the cockpit, if the cockpit is open transom. Like a propane locker, it should contain nothing but the containers and perhaps a few related items. Our F-24 has an under-seat locker for a portable gas tank.

We keep gasoline additives, oil, small propane cyclinders beside it, and nothing else. Any fumes or leaks flow out the transom. Our prior boat, a PDQ cruising catamaran, had an installed gasoline tank in the bridge deck. We used this space for dinghy gas, small propane cylinders, additives, and oil, funnels and siphons, and nothing else. It was sealed from the boat and vented down through the bridge deck, to the open air below. Building a safe flammables locker would not be a wasted effort for a long-term cruiser (see “Safe Options for Stowing LPG on Deck“, PS July 2022).

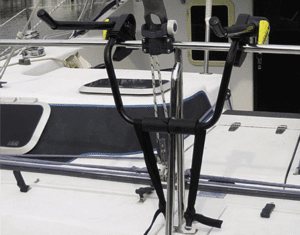

BIKES ON RACK

Bike racks for cars serve well for many coastal cruisers. No need for a custom rack. You can convert an auto rack to fit many typical scenarios. For details on this DIY project see “Stowing Bicycles on Boats,” PS May 2019.

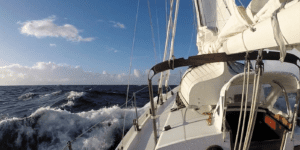

We’d rather keep everything below. There’s nothing like a clear deck when the weather turns sour. But sometimes space is tight and it is possible to live safely with deck cargo. Put some thought into keeping it out of the way, well secured, and safe against green water impact. When you’re done with the cruise, strip her back down and you’re ready to race or go daysailing.

On most cruising boats, the largest item requiring stowage is the ship’s tender. The obvious answer is an inflatable dinghy, but many cruising sailors, prefer the faster, more rugged rigid inflatables. And there are still plenty of hard dinghy fans (see “Making the Dinghy Decision,” PS March 2022)

1. With planning, a hard dinghy can fit under the boom on boats like John Stone’s completely rebuilt Cape Dory 36 Far Reach (www.farreachvoyage.com).

2. Some simple modifications can turn the boom into a lifting cradle for a heavy rigid inflatable boat. Usually all that is needed is a lifting bridle and a block and tackle with luggage tag loop of webbing or rope to secure the tackle to the boom.

3. Not recommended for offshore work, a cradle on the sugar scoop transom offers a convenient place to keep an inflatable-floor dinghy during short daylight passages in protected waters.

4. Inflatable-floor dinghies can be stowed in deck inflated. However, their main selling point is the ability to be deflated and stowed in a bag on deck or in the lazarette.

Along with widespread acceptance of furlers came the disappearance of sail lockers. Builders would rather sell more cabin space than useful storage. My Stiletto 27 (hank-on sails) and PDQ (furling jib but a free flying cruising chute) both had voluminous sail lockers. My current boat, the F-24, has none at all, in spite of having large head sails (chute and reacher) that cannot stay rigged.

A traditional solution was rail bags. Racing boats still use them for sails that may be needed on deck in the next day or two, as sailing conditions change. Cruising boats that use hank-on sails often have a squat bag at the forestay to contain a sail that has been lowered, but with the hank left attached, good for evenings and motoring.

There are plenty of horror stories as well. The sails get soaked and heavy, and the bags fill with water, and just a little pressure from green water can wash them overboard, sometimes bending stanchions and damaging bases. Maybe there is a better way.

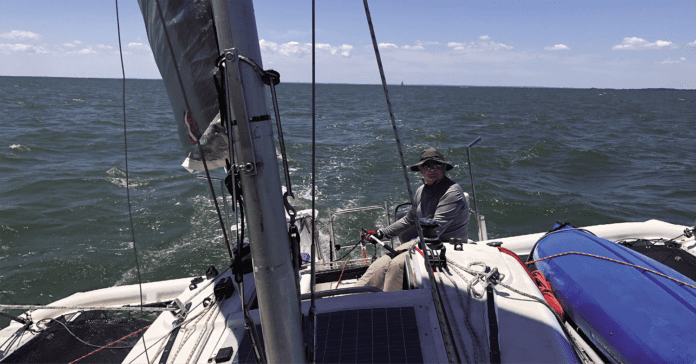

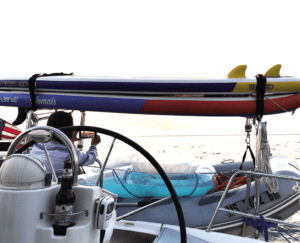

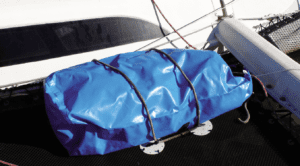

Most recently, we started using a dry bag lashed to the wing net of our F-24 as a reacher sail bag. The sail is on a furler, and in principle can be left aloft, but it is made of vulnerable Mylar and Kevlar, has no UV protection strip, and creates more windage than desirable for sailing up wind or while at anchor.

The reacher is easily lowered, but it takes too much space in the compact cabin when cruising, and derigging the furler line, halyard, sheets is a pain. Instead, we furl the sail, coil the lines, and put the whole deal in a dry bag.

The process takes only a few minutes, and the aggravation of re-rigging sheets and the furler line is eliminated. The sail is stored in a breathable bag when we are away from the boat. We thought $79 for a 200L bag was a pretty good deal for keeping a big sail out of the cabin (see Photo 1).

It’s a cheap dry bag, and after just a few day’s sailing the lashing lines left a few visible chafe marks. We’ll either glue on patches or lay a protective sheet over it before lashing it down. The bag could have been smaller, if we were willing to pack the sail more carefully, but we’d rather have the larger bag and compress it down with straps and by squeezing the air out before sealing.

Tie-down ropes pass through a D-rings built into the dry bag to keep it from slipping athwartship. The tie down padeyes were 4-inch diameter disks cut out from a fiberglass shower liner. Nylon webbing straps attached to the disks formed the tie down eyes.

The 200-liter size is about the largest that is widely available, and perhaps that is a good thing in terms of the forces involved.

Our obsession with accessories for our bikes, cars, and boats have inspired dozens small companies meeting our mounting needs. Often the best bargains can be found outside the marine market, but choose carefully. Some materials won’t last long in the harsh saltwater environment, and others like anodized aluminum will endure, but only with regular rinsing and liberal use of anti-seize coating on any fasteners.

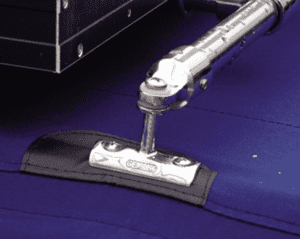

1. Gemini post bolts can mount on canvas without leaking (www.geminicanvas.com)

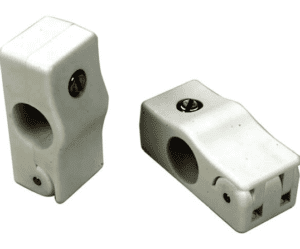

2. West Marine nylon clamps can be used with a variety of rail-mounted holders and brackets.

3. Nilight anodized aluminum rail clamps for autos are a bargain at $11 a pair (www.nilight.com). Prevent fastener corrosion by using an anti-seize coating (see Tef-gel vs. Lanocote, PS March 2017).

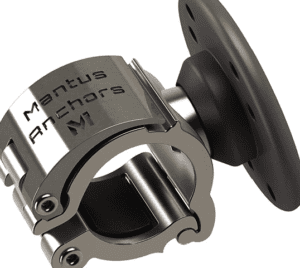

4. The Mantus stainless steel bracket with mounting pad (www.mantus.com).

5. Although not designated for marine use, load-certified 316 stainless steel bolt hangers for climbing serve fine for tie-downs. Monitor for corrosion (www.metoliusclimbing.com).

6. The Sealect stud (www.sealectdesign.com) and our own do-it yourself bond-in mounting bolt provide excellent support for solar panels (see “Securing Your Solar Panels,” PS March 2018).