In the marine trade, manual bilge pumps are big business. Thats because virtually every boat in the world has at least one. Two or even more are usual.

In the days of hard-driven clipper ships, sailors on old leakers sometimes served part of every watch on the pumps. Lifting bilge water in a pump well that long was hard work that called for two men on each end of the double-acting beam lever.

Aboard yachts, where such work is anathema, removing bilge water is done with electric pumps. However, many boat owners use a manual pump to deal with minor amounts of bilge water.

And, of course, when youre in terrible trouble with no electric power, you hope the manual bilge pump is big enough and good enough to ensure a postponement of your demise.

The question always arises about whether any of these pumps will save your boat if it is holed. Nigel Calders excellent book, The Boatowners Mechanical and Electrical Manual, contains a table displaying flooding rates of various sized openings at various depths, expressed in gallons per minute.

For instance, a 1″ diameter hole a foot below the waterline will admit 20 gallons of water a minute. The same hole 5′ below the waterline will admit 44 gallons. A 6″ diameter hole a foot down will admit 707 gallons per minute; 5′ down, it will admit 1,581 gallons-or more than 90,000 gallons an hour.

However grim these numbers are, a good pump may clear the bilge, staunch or slow the flow while a search is made for the hole and repairs are made.

Its been 10 years since Practical Sailor tested manual pumps. For this round 19 pumps were assembled. Most of them are from three major manufacturers, Edson and Bosworth (Guzzlers) of the United States and Whale of England (which also makes Henderson pumps). Others are from Jabsco, Rule, Beckson, Plastimo and a Dutch company called Raske & van der Meyde BV.

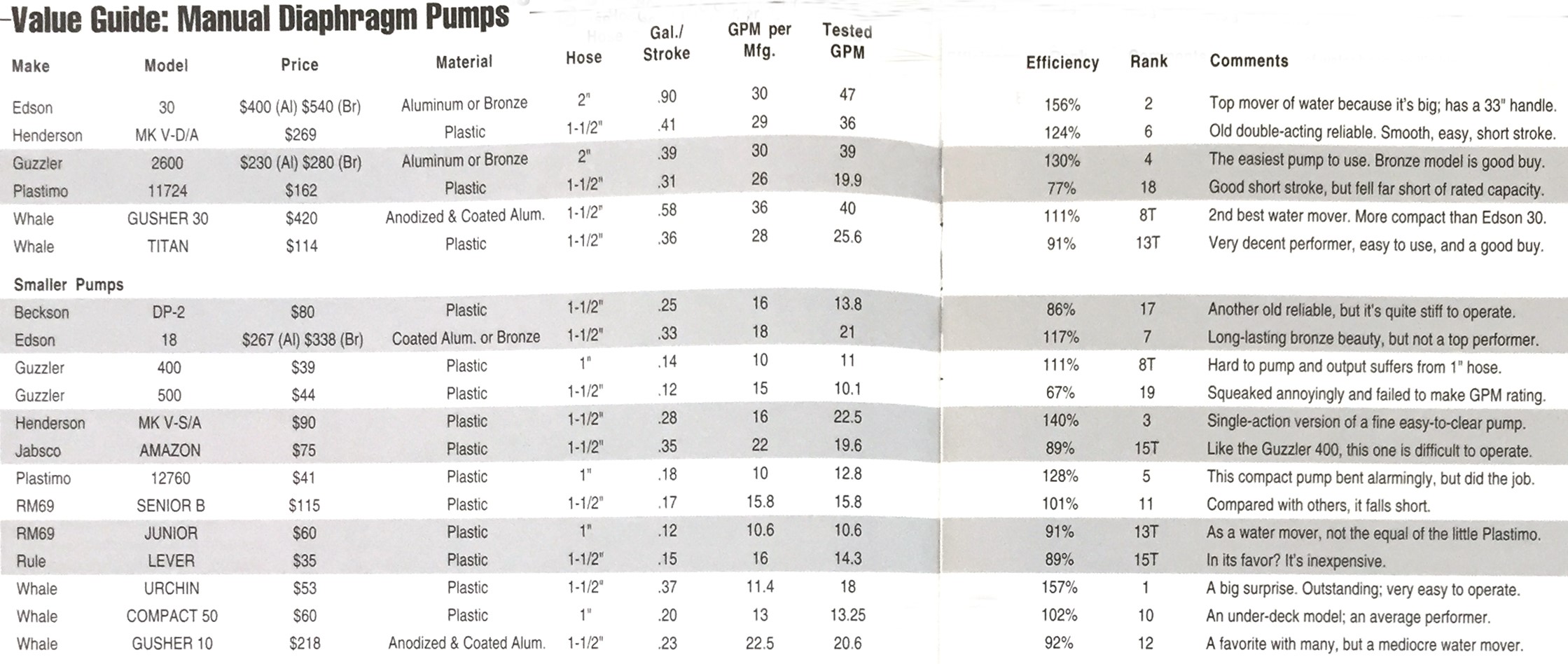

The pumps are shown in alphabetical order on the chart on page 6. The six big pumps, those that are supposed to permit you to move about 30 gallons per minute (GPM) are grouped on the top portion of the chart. The smaller pumps are on the lower part of the chart.

No effort will be made to deal with bilge pump locations, strum boxes, check valves, hoses, siphons breaks, bilge alarms, etc. A thorough discussion by PS Editor at Large Nick Nicholson on the subject of manual and electric bilge pump installation was in the October 1, 1997 issue.

The test does, however, concern one important facet discussed by Nicholson. It is the matter of lift. Lift is the distance from the end of the suction hose (low in the bilge) to the highest point (usually the discharge point or a loop) in the exhaust line.

Most pumps are rated by the makers in what is called open-bucket or open-flow conditions. That means the intake is at the same level as the discharge, both level with the pump. Its unrealistic, but does provide some guidance for a buyer.

On most boats, the lift is measured in feet and, the greater the lift, the more pressure is necessary to move water up and out of the boat. Obviously, with increased lift, the pumper puts out more energy to remove 30 gallons of water a minute with a pump rated at 30 GPM…or, conversely, if he uses the same energy, he will move less water.

Although it doesn’t matter much whether the lift is on the suction side or the discharge side, the pumps efficiency (whatever its real or stated capacity) matters a lot.

How much does output vary?

The Efficiency Factor

Thats one of the things that this test attempted to pin down. Which pump comes closest to meeting its manufacturers rating for GPM? This might be called an efficiency factor.

All pumps were tested with a 3′ lift; the chart displays those figures. How much difference the vertical intake/discharge distance makes was checked by testing some pumps at a 6′ lift, and comparing the figures with those obtained in the 3′ category.

For the larger pumps, the reduction in gallons pumped was as much as 30%. For the smaller pumps, the reduction was less significant-as little as 10%.

All pumping was done at a maximum pace, hard but not frantic, with the emphasis on putting forth the same energy in each minutes worth of pumping. Obviously, if one were stronger or could work faster, the output would increase. If a pumper slowed to an easier pace or grew tired, the output would drop.

The laws of physics dictate that the amount of water moved is linked directly to the amount of energy expended.

The only way this could be different would be if longer handles were fitted. A longer lever would permit either an increase in the rate of flow or a greater volume of water that could be produced before exhaustion. Several pump manufacturers offer handles in different lengths; if there is swing room, the longer ones are a good idea, especially for the high-capacity pumps.

(Calder, in the above-mentioned book, explains how to calculate the effect of bends and of smooth vs. corrugated tubing. Its enough to strongly suggest that when installing a pump, use smooth-walled hose and keep the runs as straight as possible. The PS test set-up did not experiment with elbows, bends and various kinds of hose.)

To keep the playing field absolutely level, all pumps were fitted with the same type of hose-1″ and 1-1/2″ Shields Series 148 vinyl that is extra heavy (to avoid collapsing under negative pressure) and smooth walled (to avoid hampered flow); the 2″ hose needed for two pumps (the Edson 30 and Guzzler 2600) was Shields Series 210 Versaflex. The hoses were secured with AWAB 316 stainless clamps, and tested for air leaks that could affect pumping rates. An air leak, however tiny, in the suction side drastically reduces the pumps efficiency; on the discharge side, it will be a leak.

On the test bed, the intake and discharge hoses came straight out of the pump and made one 90 gentle bend to the water tanks. The pump handles were at a convenient height. In fact, other than the lift factor, the set-up was designed to make it easy for each pump to produce its maximum…as delivered by an average man pumping hard for one minute.

Aboard a boat with a group of strong-armed pump operators working in shifts, it might be said that with a 30 GPM pump delivering full capacity the team could move 1,800 gallons of water an hour, maybe more. However, note that this isn’t even as much as would pour in through a 1″ hole 5′ below the waterline and is insignificant compared with the water that would flow in from a 6″ hole a foot below the waterline.

It is very difficult to even guess how much an average human, using any kind of manual pump, can expect to move in a protracted emergency. Sooner or later an old dictum about a frightened man with a bucket would kick in.

Material & Workmanship

The test plan originally included the disassembly of each pump, not only for an examination of its diaphragm, diaphragm pressure plate, valves, rocker arm, hinge and pressure plates but also to assess how easily it might be serviced.

This phase of the test probably would have favored the metal-bodied pumps, those made of cast bronze, left raw, or aluminum, anodized or epoxy coated.

Perhaps the clearest indication that this would be unwise are the Henderson pumps. Henderson was purchased a few years ago by Munster-Simms Engineering Limited, the maker of Whale pumps. However, because of the popularity of the Henderson pumps, the Irish company continues to make and market the Hendersons-in competition with itself!

Further, after dismantling several of the pumps, little could be learned by examining their interior parts, and it appeared that servicing any of them would be, at the worst, a fussy job that would grow difficult only if neglected for a long time. Several service kits were checked, to make sure.

An indication of the potential problems, especially with pumps containing parts made of dissimilar metals, can be seen in the photo on page 5 of a Whale Gusher 10 sent by a reader, Gary Irving, of Newton, Massachusetts, to Practical Sailors Gear Graveyard.

The pump was aboard Irvings Niagara 35. The pump was original equipment, circa 1979 (it came with the boat), and performed well for about two decades, being used weekly to clear the bilge. Irving bought a re-build kit, but when the old pump was stripped, it revealed a seized nut on the pump diaphragm pressure plate. The stainless bolt and nut in an aluminum housing suffered from immersion in saltwater. The flap valves also were stiff. Other than that, the pump was in working order.

The lesson? Even a good quality pump, if its expected to last a long time, should every couple of years be dismantled, inspected and cleaned up-which should include removing accumulated salt encrustation and the application of a bit of Vaseline as well as anti-seize treatment (maybe Loctite #242, Tef-Gel, Permatex or any equivalent) for all threads. This is especially true for aluminum-bodied pumps with stainless parts and fasteners. Depending on their location, they can be subject to severe corrosion. (See Gear Graveyard, October 1, 1998.)

The Bottom Line

These 19 pumps were used vigorously, even roughly. They were clamped tightly to the workbench, usually with but two of their customary four mounting feet.

During the pumping, several of the small plastic pumps bent alarmingly. But nothing broke. No cracks. No handles bent.

The conclusion has to be that the pumps are well made and can stand up to fast, strong treatment.

The test wound up being a pumping evaluation.

On the chart, one column displays gallons per stroke. Naturally, the larger pumps dominate this category.

The next column to the right is the manufacturers GPM rating. Next to that is a column showing how much was pumped in one minute bursts (at a 3′ lift) by Practical Sailor. The column headed Efficiency shows what percentage of the manufacturers rated GPM was pumped with each model. For many pumps, the figures were surprising, considering that all pumping was done at a 3′ lift. However, remember that the pumping was done vigorously, but just for one minute.

The next column ranks them all according to efficiency.

Edsons big 30 GPM classic, whose design hasn’t changed in years, ranks first among the large pumps. If you have room for it, this juggernaut, preferably the bronze model, moves water like no other-if you have the arm for it. With the long handle supplied, however, its not particularly hard work, certainly less than equivalent pumps with shorter handles. Ranking next are the Guzzler 2600, the Whale Gusher 30 and the venerable Henderson Mk V D/A (double action).

If space was limited but you wanted a metal pump that would, with proper servicing, last virtually forever, the best big pump buy, in our view, would be the bronze Guzzler 2600. Besides pumping 130% of its rating, it won praise as the easiest of all to operate. Also a good buy is the very decent-performing Whale Titan.

For a smaller pump, one stood out. The compact, plastic Whale Urchin, despite being fitted with 1″ hose, moved a lot of water, is among the easiest to pump and has a modest price-both for the standard version and the through-deck model. It had the highest effiiency rating of all, albeit just a percentage point above the big Edson.

Any of these pumps can be mounted on horizontal or vertical surfaces. Through-deck plates are available for many.

For difficult mounting situations, some have cases with a choice of two mounting faces or have variable handle positions. They are the single-action Henderson, the Whale Gusher 10, the Guzzlers, the Jabsco Amazon, the Beckson, the Rule and both the large and small Plastimos.

Contacts- Beckson, 165 Holland Ave., Bridgeport, CT 06605; 203/333-1412. Edson, 146 Duchaine, New Bedford, MA 02745-1292; 508/995-9711. Guzzler, Bosworth Co., 930 Waterman Ave., East Providence, RI 02914; 888/438-1110. Henderson, Imtra, 30 Samuel Barnet Blvd., New Bedford, MA 02745; 508/998-0001. Jabsco, ITT Industries), 1485 Dale Way, Costa Mesa, CA 92626; 714/545-8251. Plastimo, Simpson-Lawrence Inc., 6208 28th St., E. Bradenton, FL 34203-4123; 941/753-7533. RM69 (Raske & van der Meyde BV), Titan USA, 90 Hatch St., New Bedford, MA 02745; 508/999-0050. Rule, Cape Ann Industrial Park, Gloucester, MA 01930; 978/281-0573. Whale, Imtra, 30 Samuel Barnet Blvd., New Bedford, MA 02745; 508/998-0001.