In this December issue, as usual, we present a short list of products that made an unusually strong positive impression on staff and contributors in the course of the past year, usually because they embody clear superiority and innovation, as well as practical value.

For the year 2002, here, in no particular order or rank, is the gear that came charging through.

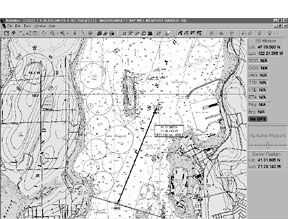

Nobeltec VNS

Evaluating navigation software is not a task for the timid. We used to throw out those with fuzzy charts, the ones that wouldn’t transfer waypoints to or from a GPS, and those that couldn’t interface with both the autopilot and the skipper’s bunk. Nowadays, they all have crisp charts; you can download your scrambled eggs and coordinate bottom contours with your best Banana Republic shorts.

What’s really tough is comparing the dizzying array of features and then-to compare one with the other-consider which ones are most important and which are OK, but a mite frivolous.

In our first navigation software report, which ran in the February 1 issue, we looked at the Max-Sea Navigator (whose strength is its distinctive simplicity); both CAPN First Mate (a very thrifty buy, but comparatively limited) and Voyager (a longtime leader, with an amazing range of features), and the Nobeltec Visual Navigation Series 6.5. In an update feature in the August 1 issue, we added software from Maptech, Raymarine, and Fugawi.

PS picked Nobeltec, not only for its flexibility and documentation, but because it takes a huge step forward by its excellent use of vector charts.

On Practical Sailors 31-point comparison, Nobeltec picked up 10 excellent ratings, compared with seven for the nearest competitor.

The report ran in the Feb. 1 issue.

3M Oil Absorbent Sheets

Compared with the clean-hands work of evaluating navigation software, the task of testing oil absorbing pads, socks (a.k.a. rolls), packets (a.k.a. pillows), mini-booms, and sheets gets messy.

Soaking up the mess is what this stuff is supposed to do. Some do it in minutes; some take a long time.

Even a little oil spill must be cleaned up. If it gets in the bilge and goes over the side, it’s criminal. If it sloshes around, it stains everything an unpleasant color, and it stinks for a long time.

PS tried six flavors-the MDR Oilzorb Engine Pad, the MDR Oilsorb Mini-Boom, 3M’s oil absorbent sheets, Enviro-Bond’s Captain’s Choice, Imbibitive Technologies’ Imbiber Beads, and Petrol Rem’s BioSok.

The testing was easy. A measured mix of water, oil and antifreeze was poured in big plastic tubs . Drop in the oil absorber. Agitate. Wait a couple of days. Agitate again. Wait a couple of weeks. Agitate-whenever you walk by and feel moved.

This goes on for months, because, for instance, the BioSok requires a year to completely biodegrade the oil it has taken in. The report finally was ready for the March issue.

Because it’s a good idea to whip that oil out of there the minute you can, we prefer the simple wicking type of absorber made with millions of polypropylene fibers that have millions of air pockets to hold the oil or gas that is picked up by capillary action. (These things of course require responsible disposal-not always easy, but absolutely necessary.)

The absorber that worked best, fastest, and for the least money -in a few minutes, in fact-was 3M’s Oil Absorbent Sheet, at $1.19 each.

Refer to the March double issue for more information.

Pelican Dry Box

Never mind keeping your powder dry-these days the delicates include papers and passports, cameras and handheld electronics, first-aid gear, batteries-the list is very long.

It’s not often much of a problem, but on wet boats in bad weather, the sogginess penetrates perniciously.

A good defense is the so-called “dry box,” which is supposed to be made of water-impermeable materials-plus easy-to-use lids that have moisture-defying seals.

Before we could even plan how to test dry boxes, we had to decide on sizes and prices. (There are a lot of examples out there.) In the end we collected six high-end boxes no bigger than small suitcases and a couple of inexpensive models about the size of ammo cases. They ranged in price from $12.99 to $277.

The boxes were tested five ways. They were dropped twice (from 5′ and from 10′) with heavy loads inside. They were sprayed with water. If they survived that, each was subjected to a very brief surface dunk (as though you’d dropped the case over the side, but snatched it out like it contained the family jewels). Finally, we dove them down to their rated depth, and if they passed that, took them to 23′.

The two cheapo models didn’t get far. The most expensive one, the only aluminum case, leaked-but had made no claims to the contrary, which to our way of thinking disqualifies it for use aboard a wet boat.

The boxes from Otter and Underwater Kinetics did quite well.

But, as reported in the April 15 issue, the Pelican 1500 was the overall winner.

Icom IC M1V Handheld VHF

In the world of technology, nothing seems to be have improved faster than handheld VHF radios. Only a couple of years ago, these things were twitchy little devils.

No longer. These radios have been waterproofed, reduced in size, and given much greater battery capacity. Although low-priced consumer items, they now rival the extremely expensive commercial versions.

With improvements coming along so fast and furiously, these radios demand Practical Sailor’s regular attention. This year, more than a dozen were called to the line for close examination and testing.

The manufacturers? Standard, Uniden, Simrad, Raymarine, Icom, and Shakespeare.

Each was bench-tested against a well-calibrated communications service monitor. Measured were transmit performance, receive performance, transmit audio, and receive audio. Next came a subjective session aimed at ergonomics and the quality of the display. Finally, each radio was immersed briefly in a bucket of water, tested immediately, and retested the next day. To their credit, seven of the 12 models survived the water test; only two were below average or unacceptable.

The results were published in the May 1 issue. With an almost perfect score, the ICOM IC-M1V, the company’s top handheld, was the winner by a hair. It’s expensive, but the $250 bang-buck is readily apparent.

Standard Horizon’s HX350S, at $200, won the Best Buy rosette.

A small horde came thundering home with good marks. First among them were Standards HX460S, Raymarine’s Ray 102, and ICOMs IC-M2A.

ITT Night Mariner 160

Night vision equipment is one of the many trickle-down technologies that benefit sailors. Practical Sailor got on these devices back in 1994; the June 2002 issue carried our third report.

Night vision glasses generally are divided into what has come to be called Generation 1, 2 or 3. Generation 1 glasses require some infrared light, usually supplied by the scope. Generation 2 devices work best with moonlight. Generation 3 glasses are quite happy with starlight.

Buyers have difficult choices to make, between binoculars, monoculars and goggles. And the price spread is enormous, from about $200 to 10 times that amount.

Practical Sailor scanned marine and mainstream sources and the Internet, and picked 11 models for the latest test. They were passed around to personnel in maritime search-and-rescue, police work, and fire-rescue units, and wrung out in various conditions by PS contributors and staff.

After all the testing and melding of opinion, it all came down to these conclusions:

1. The best all-around device for serious marine use was ITT’s Night Mariner 160, a nice-to-handle Generation 3 monocular with bright, crisp images. It’s waterproof. It floats. It has a goodly list of options. Naturally, it carries a goodly price tag, too, with a basic price of $1,640.

2. The bang-for-your-buck winner was Night Owl’s Explorer G2 (NOXG2), a Generation 2 monocular that for a little more than $900 offers some admirable features.

3. Those on restricted budgets might be happy with our economy choices, two Russian-built, Generation 1 monoculars that despite carrying different names, appear to be the same. They are Bushnell’s Model 26-2042W ($307) and Night Owl’s NONO3Y ($200).

Force 10 Barbecue Stove

Moving right along now, we had fun-sort of-with our latest test of stern-mount barbecues.

When we did them 11 years ago, they were mostly charcoal-burning; this time we focused on ones fueled by propane gas. That’s progress, isn’t it? The grilled fish might not be quite as tasty when done with gas, and you no longer get to annoy your neighbor anchored downwind with noxious starter fuel fumes, sparks and ashes. But you don’t have to double-bag that clumsy, greasy, dirty thing to store it in the lazarette. The gas-fueled grills stay cleaner.

The six models from five manufacturers were closely examined-especially to identify such sterling features as a “radiant screen,” a “circular continuous rim of fire,” a “dome system,” etc. Barbecues seem to lend themselves to a couple of extra tablespoons of ballyhoo.

Our testers fired them up and cooked ground meat (a.k.a. burgers) and a square of pizza dough (to test the evenness of the heat).

It might be logical to say that the more compact kettle-based barbecues are best for small boats and the cylindrical models are for big boats, which can tolerate the weight and have the room needed for stowage. Bigger boats also might be said to have more mouths aboard.

When sunset came and the fires died down, our testers turned in their report cards. Of the kettle types, it was a draw between the Magma ($129) and Si-Port II’s Sport Extreme ($150).

Of the larger cylindrical grills, the use to which you intend to put them and the space you have to store them might dictate your choice. They’re all well-made.

If we had to choose but one from the five, it would be the moderately priced Force 10 ($185).

To make the July 1 report as exhaustive as possible, PS noted that if you really can’t envision sailing without a broken bag of charcoal in that cockpit locker, most companies still offer charcoal models, which are the same without the gas burner and regulator.

MPS Perfect Pole

There’s usually a way (a practical way, as befits us) to avoid the horrendous expense and baffling data-spew involved in subjecting simple gear to full-blown, professional lab testing.

For instance, our most recent test of boat poles, as explained in the August 15 issue, involved mounting a bathroom scale on a tree and pushing against it with each boat pole. The pulling test, using the same bathroom scale, required a lot more thought and some cobbled-up apparatus. After the pushing and pulling came bending, flotation, deployment, and actual deck scrubbing.

There were seven telescoping boat poles in this test. Included were twist-locks, which have an internal cam that grabs or releases when the pole parts are twisted, and pin locks, which have spring-loaded pins on the inner tube to engage holes in the outer tube. Either type must be engineered and manufactured carefully to work smoothly and reliably.

All were multi-purpose, meaning that they stood in as traditional boathooks but also were mounting platforms for mops, squeegees and even nets.

After exhaustive yanking, snapping, jerking, changing heads, pushing and shoving, we found no perfect telescoping boatpole in the lot. However, MPS’s aptly-named Perfect Pole ($29.95) came clos. A pin-lock pole, it’s a good, sturdy design with a channel to keep the pin and holes aligned. It can be operated quickly, by feel.

Hevea and Musto Seaboots

For the evaluation of seaboots, Practical Sailor set a top price of $100 (you can pay scads more if you want to) and gathered up a bunch of candidates, including three pairs of commercial fisherman’s boots. These proved heavy and, with bold tread patterns, couldn’t match the traction of yachtsman’s boots.

The “just right” boots were those from Hevea Pacific ($64) the Musto M1s ($85). And, lo and behold, they’re just about identical in weight, height, reinforcements, color, soles, and insoles-everything except the gaiters and liners. So take your pick-name or price.

We also took a look at dinghy boots (a.k.a. racing boots). These are short-in-the-calf boots, light and flexible. To make them fit better, they usually have zippers, laces or hook-and-loop closures.

Of the five dinghy boots, Ronstan’s Zip Dinghy boots ($54-$67) and Musto’s M3 One Design model ($59) appeared to us to be the best.

Casio SPF-40 Marine Watch

A trusted watchmaker friend once explained that the smaller the watch, the less accurate it was, and also the less fragile. He said that there was no such thing as a waterproof watch, unless it had a bellows to accommodate the drastic air volume change when a sailor jumped from 95 air into 65 water.

These one-time truisms were especially true for yacht timers. Countdown racing watches used to be pocket-watch sized, quite accurate, and not too waterproof. (We note in the catalogs that pocket watches seem to be having a little comeback these days, but it’s unlikely to last.)

As with most things electronic, watches now do everything but get your mother-in-law off to the bus station. Sailing watches are keeping pace-performing more functions in less volume, while keeping their accuracy and staying quite waterproof.

Practical Sailor gathered up 10 watches from seven manufacturers, and assessed them in 24 different charted categories ranging from case material to water resistance to moon data to weight to readability to just plain comfort. The price limit was arbitrarily set at $350, which eliminated a lot of watches, including the archetype of all marine watches, the Rolex Submariner, choice of James Bond and plenty of other swift dudes. The Submariner, as cool and accurate as it may be, is not exactly a modern watch. It has gears, a spring, escapement, bearings-and it ticks.

The price range for watches PS examined ranged from $50 for a Del Mar Tide Watch, to $70 for the very famous Casio G-Shock DW6100 (one of the most successful watches ever made), to $325 for the Suunto Yachtsman, a carbon-fiber/aluminum wonder from Finland; and $349 for Casio’s Pathfinder GPS, which is a wonderful gadget, but not an urgent buy for those who already have GPS aboard.

After all the fun, we had to concede that the choice of a watch is a very personal undertaking, further involving many functional factors.

But when the business of choosing just had to be done, we had to put aside the elegant Citizens models-the EcoDrive Diver ($166) and the EcoDrive Sailhawk ($217); the Seiko Kinetic SMY042 ($339), and the Luminox Navy Seal II ($200). When the sun went down, the overall choice was the Casio Sea Pathfinder ($220), a fine all-round sailor’s watch that, although a bit clunky, has tide, compass, barometer and timer functions that are easy to set and use.

By the way, as we mentioned in the article (October 15) there’s a big churn in the watch industry. After the article came out, we got messages from two readers who said they’d heard that the SPF-40 was discontinued. We checked with Casio. It’s still in production, and is still available from plenty of sources (go to www.google.com and enter keywords “Casio SPF-40.”) But next week it may be gone. Sic transit…

West Marine WM-F8C Funnel

It took a long time, but Practical Sailor was determined to find out if those diesel fuel funnels really filter the oil as it goes into your tank.

After all, they’re a nuisance. They slow down your refueling and furnish the dock boy with an excuse to make snide comments. And they’re messy to clean and stow.

After dozens of phone calls, talking almost endlessly to experts, PS learned a lot about diesel fuel.

For the testing, we combed the market and came up with 10 filter funnels. They ranged wildly in price-from $2.80 (for a red plastic RC Fill-Fast with a simple brass screen) to $130 (for the renowed Baja, a big cylindrical device which has three filter elements).

The testing really was a challenge round to see if any simple funnel could do as well as the Baja.

It was quite interesting. None of the funnels remove every bit of water and dirt. But a new funnel developed by West Marine, priced at $29, easily outdid the expensive Baja by means of a simple design stratagem: The funnel has a sump that traps water below the Teflon-coated stainless steel filter element.

As for the question: Should you filter the fuel at deck level, we think the answer is yes, or at least “Why not?” Considering the massive headache you can avoid down the line, so what if it takes a few extra minutes to tank up, especially because you can do it efficiently with the small, cheap, West Marine Model WM-F8C.

Contact – Casio, 973/252-7570, www.casio.com. Force 10, 604/522-0233, www.force10.com. Hevea, Euro Marine Trading, 800/222-7712, www.euromarinetrading.com. ICOM, 425/454-8155, www.icomamerica.com. ITT, 800/448-8678, www.ittnightvision.com. MPS Swobbit Perfect Pole, 800/362-9873, www.swobbit.com. Musto, 800/553-0497, www.mustoclothing.com. Nobeltec 800/946-2877, www.nobeltec.com. Pelican, 800/473-5422, www.pelican.com. Ronstan, 727/545-1911, www.ronstan.com. West Marine, 800/262-8464, www.westmarine.com.