Perhaps the biggest surprise during our 30,000-mile circumnavigation was just how critical the engine is to a cruising sailboat. We motored or motorsailed almost 25 percent of the miles that passed under our keel. The engine also provided battery charging for everything from lighting to making fresh water. It drove the refrigeration system, and made hot water.

This percentage of time under power is not unusual. There are parts of the world where motoring is the norm, if you want to get anywhere in a rational amount of time. The South China Sea and Java Sea, for example, have notoriously light and fickle winds, as do other parts of Southeast Asia. Headed north in the upper half of the Red Sea, your two options are usually to beat into 35-knot headwinds, or wait for calm periods and motor. The same goes for parts of the Mediterranean.

Yes, we do know people who, not necessarily by choice, do without a propulsion engine for extended periods of time. Except for the extraordinary few for whom cruising without an engine is a conscious choice, a reliable engine, plenty of spares, and a schedule of preventative maintenance that is religiously adhered to is critical to the success of any cruise.

When we began unloading Calypso after returning to the U.S., the sheer volume of parts and service items for the engine and its associated systems was pretty indicative of how much we count on it.

Engine spares are among the heaviest, space-consuming, and expensive items you will carry on your boat. It’s true that you can get basic engine consumables in all but the most remote parts of the world. It’s also true that relying on local sources of supply in out-of-the-way places can add an enormous amount of stress to your cruising.

Even in areas of the world where engine spares are readily available—Singapore or Australia, for example—it may be a logistical nightmare to try to get to the local source of supply, or they may not have what you need in stock at that particular moment. In countries with language and cultural barriers to easy communication, finding parts may be frustrating or impossible. If it’s not in stock, you can’t count on getting it in a rational timeframe. The bottom line is simple: carry it with you.

Fuel Filters

By engine spares, we mean consumables as well as engine parts. Yes, we found Racor fuel filter elements all over the world, but sometimes we found one when we wanted three, or found 30-micron elements when we wanted two-micron filters. In Thailand, we spent an entire day scouring dingy hardware stores looking for Racor filter elements, finally ending up with two after investing six hours of street-pounding time in stifling heat. We still aren’t sure how to say “Racor fuel filter elements” in Thai (or Arabic, or Turkish for that matter), and it’s not much fun to traipse around with a stinking old filter in your backpack.

Remember that you probably have two fuel filters: a remote filter between the tank and the engine, and a factory-installed filter on the engine itself. You may be able to find Racor elements, but the engine-mounted filter may be more difficult to locate. For protracted cruising, you won’t go wrong by carrying a dozen of each filter. If, for example, you get a load of contaminated fuel somewhere—and this happens regularly, everywhere in the world—you may go through filters at an astonishing rate until you can clear up the problem. Half a dozen spares can turn into no spares at all in only a few hours of engine operation.

Engine Oil

If you’re picky about engine oil—and you should be—you may find it difficult to locate the kind of oil you’re used to. Be aware that in many parts of the world, the oil you are familiar with may have a different local name, even if the brand is the same. It may also smell different, and even look different, from the oil back home.

Generally speaking, you’ll be able to find usable diesel engine oil almost everywhere you can buy fuel. The operative words here are “almost” and “usable.” We try to carry a minimum of enough oil for six changes, or about 600 hours of engine operation. Remember to buy not just the amount of oil needed for the change, but for any topping-up that may be required between changes.

My obsession with engine oil and changing oil at the proper intervals has become a bit of a joke aboard Calypso. In Malaysia, I made several round trips—on foot, in the steaming heat of tropical Southeast Asia—of three miles to a Shell station, when I discovered they carried the Rimula X oil that I like to use. Carrying 20 liters of oil at a time in your backpack may be good exercise, but it’s bloody hard work.

Oil filters are another issue. There are so many varieties of oil filters in the world that you can’t possibly count on finding the right one for your engine. You may find an unfamiliar brand that looks exactly like your filter, but is it really the same thing? Are you willing to risk your engine on this?

When you find the right filters, buy them. They’re a lot harder to find than engine oil. We buy filters by the dozen, and stow them in watertight plastic boxes.

Unfortunately, as mentioned before in this column, we got an entire case of defective Fram filters in New Zealand, so it’s a good idea to install one filter from a new batch right away, just to make sure everything’s alright.

Belts and Braces

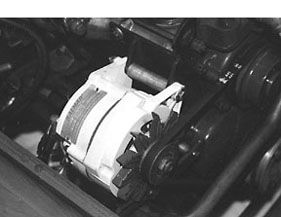

V-belts are another problem, particularly if you have high-output alternators. It is almost impossible to judge the quality of a V-belt just by looking at it. Once you leave the US, it’s very difficult to find the type of industrial-rated V-belts that you can buy off the shelf at any large auto parts store in the US. Most belts you find overseas are fractional-horsepower belts designed for automotive use. Try running a 100-amp alternator with one of these belts, and see just how long it lasts.

We bought two belts in Turkey that the mechanic swore up and down were industrial belts, the best you could buy—but they weren’t good enough. After five hours, one of the belts gave up the ghost in spectacular fashion, showering the inside of our engine box with shards of black rubber.

Needless to say, we didn’t give the second belt a chance to prove it was better.

Belts don’t last forever, and should be replaced the instant they start showing sidewall wear or cracking. As a rule, belts driving high-output alternators, which have small pulleys in order to increase output, should be replaced every 500 hours of engine operation. Belts driving large pulleys, such as those on refrigeration compressors, will have much longer life.

We finally re-configured our engine belt arrangement slightly so that we use the same length belts for both the alternator and refrigeration compressor. This has reduced the spares we have to carry, and has given us a comfortable redundancy.

Proper belts are one item that you should simply not count on finding once you leave the US. Leave home with as many as you think you will need for your entire cruise, then add a couple of spares.

Count on between 500 and 1000 hours of engine operation for every year of your cruise. If you’re going to be gone for five years, you may need as many as 10 belts for the alternator alone.

Belts that are removed based on hours of operation, rather than obvious wear, can be saved as emergency backups if you run out of new belts. Be sure to mark them as “used,” however.

Alternators

Alternators themselves are another potential weak point in the system. Most cruisers replace factory-supplied alternators with high-output models, saving the original factory alternator as a spare. This may sound good in theory, but swapping between different types of alternator may require changes in alignment, belt length, or even voltage regulation systems. Most stock alternators are internally regulated, while virtually all high-output alternators are externally regulated.

Instead, we recommend that you carry at least two identical high-output alternators: one installed, the other as a spare. In addition, carry a rebuild kit for each alternator—bearings and diodes, primarily—so that anyone rebuilding your alternators outside the US will not have to hunt for parts. There are automotive electrical shops virtually everywhere in the world that can rebuild your alternators in a matter of hours, if you have the parts. Without the parts, you could be in deep trouble.

You should also carry a spare multi-step regulator, and a spare alternator wiring harness, as vibration may eventually damage the wiring or connections.

We carried three identical Balmar alternators, and used every single one of them. While some alternators may go years without problems, there’s no guarantee of this. Particularly susceptible to heat damage are small-case, high-output alternators, which do not cool nearly as well as large-case models. In the typical tiny, crowded engine box of the cruising sailboat, there simply may not be enough airflow to properly cool a big alternator.

It does no good to carry spare alternators if you don’t know how to change them. Even if you have nominally identical alternators, pre-fit each one to make sure that there are no installation glitches, and that you understand the process of changing them completely.

On Calypso, for example, changing alternator belts requires removing the refrigeration compressor belt first. This means loosening the compressor, which is mounted below the alternator. Since I have been through the process several times, I know what size wrenches I need for each step of the job, which speeds things up dramatically. If you’ve never done a dry run, you may not know what complications you face in an emergency.

Because I have had—unfortunately—a lot of practice, I can change alternator belts in five minutes from the time I open the engine box, and can swap out alternators in 10 minutes. Needless to say, you need to have the spares close at hand, not buried somewhere that requires tearing the boat apart.

Gearbox

Probably the most neglected part of the drive train is the gearbox. Gearbox fluid does not last forever, but how often should you change it? My Perkins owner’s manual suggests checking the gearbox oil level every 400 hours, but doesn’t even give replacement intervals!

The consensus of the mechanics we asked was that the oil in a two-shaft gearbox, such as the Hurth, should be changed at least at every other engine oil change, or 200 hours of operation. Since having to rebuild our gearbox in Thailand, we have been faithful to this schedule.

Make sure you know what type of fluid your gearbox uses—it may be engine oil, automatic transmission fluid, or something else. Like every other consumable, carry enough for at least a year of service.

Water Pumps

What other engine hardware spares should you carry? You should carry enough raw water pump impellers for your entire cruise, say at least one per year. We would also suggest switching out the raw water pump cover for a Speedseal quick-change cover, so that you can check and change impellers quickly.

You should carry a complete spare raw water pump, with the appropriate hose adapters already installed. You can leave the factory impeller cover on the spare pump, and swap out to the Speedseal cover at your leisure.

Incidentally, we strongly suggest removing the impeller from any new pump and heavily greasing the drive shaft before reinstalling the impeller. You should also lightly grease the pump bore and the inside of the impeller cover. Plumbers grease, available at any hardware store, is a good all-purpose product for this application.

Although it may seem like a lot of work to actually do a dry-run pump change, you should at least check to make sure you know what is involved, what size wrenches will be needed, and what other bits and pieces may have to be removed in order to change pumps.

The one time that we have had to change a raw water pump underway, we were in the middle of a fleet of dozens of unlit fishing boats between Malaysia and Thailand, motorsailing in very light air. These types of failures do not occur when you are sitting comfortably at anchor or in a marina.

Incidentally, we carry rebuild kits for our raw water pumps, but have had poor results rebuilding these pumps. The shafts tend to wear so much that new seals don’t do the job.

We learned this the hard way. We thought we were pretty clever, having two spare rebuilt water pumps after our engine rebuild in New Zealand. To our chagrin, both of these rebuilt pumps leaked. They would have been usable in an emergency, but that’s about it. One had been rebuilt in the U.S., the other in New Zealand.Freshwater circulating pumps tend to give less trouble than raw water pumps, but a spare for this isn’t a bad idea.

Other Spares

You should carry a spare engine starter. Our Lucas isolated-ground starter is rare, heavy, and expensive. We bought a “good” used spare before leaving the U.S., and didn’t think much about it until New Zealand, some 10,000 miles later. We took it to the electrical shop in New Zealand to have it checked out, only to discover that it was inoperable. Several hundred dollars later, it was in proper working order.

The moral of this story is simple. Just because someone says a used or rebuilt piece of equipment is in good shape doesn’t make it so. In fact, we’ve had poor luck with rebuilt pumps, alternators, and starters, even though these should be straightforward jobs.

Most of these rebuilds have taken place in what you would call the “first world”—the US and New Zealand. We have actually had better luck with rebuilds in places you might not normally associate with quality mechanical work, such as Thailand. We see no pattern here, and make the comment merely as an observation.

Other basic engine spares we would carry would be a fuel lift pump and a set of injectors. Both of these could be damaged by contaminated fuel, and can be replaced without too much difficulty by a cruiser with an adequate amount of common sense, a reasonable level of mechanical skill, and the tools every long-range sailor should have on board.

The really cautious will carry a spare fuel injection pump, although this is usually the most costly single component on a diesel engine, and its replacement definitely takes you into a higher skill level.

Generally speaking, it is easier to find a decent mechanic anywhere in the world than it is to find engine spares. If you have the required parts in hand, you’re way ahead of the game, even if the work itself is beyond your capabilities.

Ironically, we suffered our only major engine problem after returning to the U.S., following our circumnavigation. Somewhere along the way, we shipped contaminated fuel that destroyed our fuel injection pump seals. It may just have been the cumulative result of using questionable fuel from a variety of sources over time. You don’t get much choice in sources of fuel in much of the world.

The repairs involved rebuilding the injection pump, rebuilding the injectors, cleaning all the fuel lines, and pumping out 80 gallons of possibly contaminated fuel still in the tank. It was an expensive exercise, but one that ran remarkably smoothly.

We discovered the problem when the oil level in the engine suddenly rose, indicating fuel in the sump. We found it because we check the engine oil virtually every time the engine is started.

Fortunately, we were in Ft. Lauderdale at the time, with competent, if expensive, mechanics at hand. Almost $2,000 later, we knew a lot more about fuel and fuel injection systems than we set out to learn.

We were lucky that our regimen of engine checks found the problem before the engine itself was damaged. The implications of this type of problem in the middle of the Red Sea, or halfway across the Atlantic, are a little sobering.

This isn’t intended to be an exhaustive list of spares or a definitive maintenance regime. It’s meant to make you think seriously about the bolt-on, screw-on, twist-on, pour-in needs of that valuable chunk of iron sitting in the bilge. If you depend on your engine—as most cruisers do—you had better take really, really good care of it.

Maryann thinks I’m a little weird because I talk soothingly to the engine every time I check it or service it. But that faithful Perkins helped us get around the world, and I owe it every minute of attention it gets. I suggest you treat your engine the same way—just ignore the snickers of your neighbors when you whisper sweet nothings to your Perky the Perkins or Yanni the Yanmar.

This article was first published on April 15, 2002 and has been updated.

Great article, directly to the point. Extremely helpful to us novices sailors.

Converting from the standard type V belt to a serpentine belt configuration will not only greatly extend the time periods between belt replacement, it will make emergency belt replacement less likely.

I have a different setup. I have a standard alternator (not a high capacity one) that uses a V-belt that is also used for a range of tractors (which I did find out the hard way in Venezuela). I did/do carry a spare alternator but have not needed it. My starter is also run of the mill and easy to find. I did have a spare that I wound up using after the orginal one got wet and started to rust, but I could easily find a replacement.

I couldn’t agree more of primary fuel filters, I had 6 to start but went through 4 of them on one not great tank of diesel. Between the filters, I’m am not too concerned about the lift pump and injectors, both survived the dirty diesel fine (even the 2 micron filter, which I replaced anyway after that tankful). I didn’t have a spare raw water pump and missed not having it. I wound up rebuilding mine but did get it replaced before too long.

I wish I had a way to polish the fuel in the tank, but sadly I don’t.