The right roller-furling headsail is as beneficial to a sailor as a good zoom lens is to a photographer. But just as the zoom lens has limits, even the best furling headsail is challenged at the extreme ends of its range. In the October 2015 issue, we explored the basic sail needs of a daysailor. For this report, the second and final in our series on headsails, we asked five professional sailmakers from around the country to weigh in on the ideal sail inventory for coastal cruising.

We narrowed the scope by defining a hypothetical client who owns a venerable Catalina 36 MkI and is looking for a new headsail(s). We added the following biographical details and requested that each sailmaker provide both stats and the reason for the sails selected.

The clients Catalina 36 MkI-standard rig, deep draft (5 feet, 10 inches)-is a masthead sloop, equipped with a Schaefer roller-furling system. The hypothetical couple who owns the boat predominantly daysails. The only racing they do is their yacht clubs annual rally-more amble than scramble. They appreciate the versatility in their one-headsail sailplan, but recognize that no single headsail can do it all. In the near future, they hope to venture a little farther from home, and they want to optimize their headsail makeover.

Please address the following in your comments: recommend a versatile furling headsail (size, material, design); define the wind range (true) that this reefable jib/genoa covers; note whether an upgrade in sail material would increase the usable wind range; suggest whether the owner should consider adding a removable Solent stay on which to hank a working jib, storm jib, or a light-air drifter/reacher; comment on a cruising asymmetric spinnaker.

Experts Weigh In

Our panel of experts represented a cross-section of the sailmaking industry. The firms they represent ranged from international brands like North Sails and Quantum that control a huge share of the world market, to relatively small specialty lofts like Port Townsend Sails in Port Townsend, Wash.

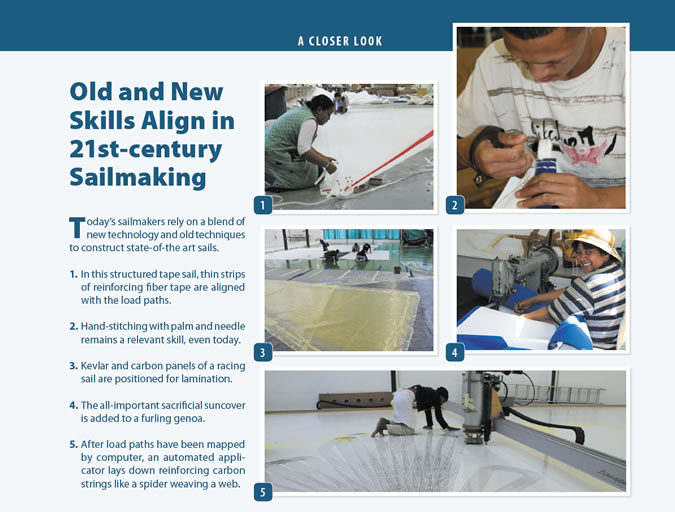

We were most interested in the experts views on construction and cut. There are three basic options for construction type: a cross-cut sail, the traditional construction-usually Dacron-that aligns the stronger warp (longitudinal fibers) with the leech loads; a radial-cut sail, a more complex construction that aligns the warp fibers with the load paths to other corners of the sail, helping it maintain its shape even as the wind increases; and string-cut or string-structured sail, an even more complicated and costly build in which high-strength fibers are aligned as needed (based on computer-assisted design) and laminated into the fabric, providing even greater stability to sail shape.

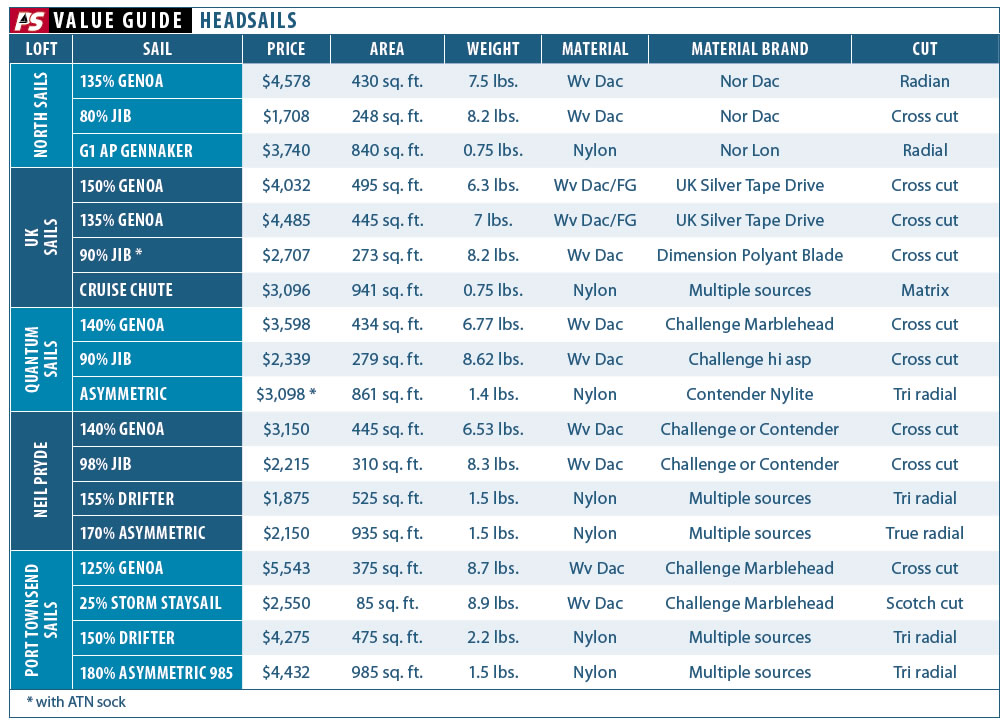

North Sails

Jonathan Bartlett has worked as a sales consultant at the North Sails loft in Annapolis, Md., since 1984. He has been racing sailboats for more than 40 years and is a three-time winner at Key West Race Week.

Bartlett suggested a 7.5-ounce, 135-percent Radian genoa. This polyester sailcloth is warp-oriented so that the tighter longitudinal fibers take most of the load. He pointed out that this sail will keep its shape longer simply due to the better layout/orientation of the yarns, which are more closely aligned with the loads throughout the body of the sail. This contrasts with a cross-cut sail, which relies more on the finish resin to stabilize bias (the amount of stretch).

Bartletts recommended sail puts the clew height just above lifelines. It has minimal skirt for easy tacking, and it comes with a rope-luff flattener and reef patches at the head and tack. Theres Sunbrella UV protection on the leech and foot.

Bartlett was not convinced that our hypothetical boat needed a dedicated heavy-air sail. However, he pointed out that if the boat was going to be sailing offshore, he would recommend a second headsail, and, for longer passages, he suggested a storm jib.

The 135-percent genoa he recommended would reef down to an equivalent area of a No. 4 jib. The luff is shorter, and the LP is a bit longer than that of a dedicated No. 4. (The LP is the length of an imaginary line drawn from the clew to the luff, where it intersects the luff at a right angle.) If desired, Bartlett said, he could broaden the reef-down patches a bit to allow for even more reduction for extended periods of sailing in heavy air.

For a light-air sail, Bartlett recommended Norths G1 AP Gennaker for short-handed sailing. He advised a snuffer sock for hoisting and dousing. The usable apparent wind-angle range with the G1 is from 50 degrees in light air (five knots or less) to 130 degrees in 17 knots true. This combination of furling genoa and gennaker will allow the Catalina to keep moving in a wide spectrum of wind conditions.

Quantum sails

David Flynn is a sailmaker with experience in all aspects of design. Prior to joining Quantum, he worked with North, Horizon, Doyle, and Sobstad during his 30-year career. His racing background covers everything from dinghies to custom big boats, but for the last 10 years, Flynns focus has been on offshore one-design racing.

Flynn believes that when it comes to easy sail-handling and versatility, it is best to keep the genoa as small as possible. He suggests building only enough size to be able to drive the boat reasonably well in light to moderate winds. The more light-air efficient your boat happens to be-and the larger the mainsail is relative to the headsail-the smaller the genoas LP can be. This is even more valid if you are the type of sailor who turns the engine on when the wind gets light.

With regard to materials, Flynn presented three choices for the cruising sailor: classic woven polyester (Dacron made in a cross-cut panel layout), composite construction using pre-made materials usually in atri-radial panel layout, and composite construction using advanced one-piecemembrane construction. In the end, he recommended a 140-percent genoa of woven Dacron, a 90-percent jib, and an asymmetric for our hypothetical Catalina 36, but he also pointed out that composite constructions might be an option some sailors would consider.

In Flynns view, the cruising sailor who is carrying around his house with him is not necessarily interested paying more for an extra 10th of a knot, but he should be interested in other aspects of performance. For the cruising sailor, the definition of performance is different, Flynn said. Its not about boat speed-though that is not a bad thing-but it is about control over heel and weather helm.

He also pointed out that the sailing hardware you rely on is just as critical as the sail itself. The furling system for your headsail, for example, needs to be up to the demands. Getting the best performance from the self-steering system and minimizing wear-and-tear on self-steering gear are also important for cruisers.

Flynn pointed out that the cruising sailors demand-the fewest number of sails to cover the widest range of conditions-presents an extraordinary challenge. In his view, this makes designing a good cruising sail more difficult than building a racing sail, where the wind range is much narrower. And even though a cruiser may claim he doesn’t care much about speed, few are truly immune to the sail-on-the-horizon effect, in which any boat within sight immediately becomes a challenger. Dont kid yourself, he said. You don’t want to get there slower than your buddies.

Port Townsend Sails

Carol Hasse, founder of Hasse & Co. Port Townsend Sails, has been a sailmaker for nearly four decades. Her offshore cruising sails are widely praised by some of the most respected long-term cruisers. Hasse is especially well-known for building durable, easily-serviced sails that live up to cruisers expectations for longevity.

Hasse believes that a well-constructed, roller-furling genoa of moderate size, proper cloth weight, and a well-engineered padded luff can be reefed to an efficient working-jib. Ive found that the fore-triangle geometry of a classic masthead sloop is generally served best by a 125-percent genoa, Hasse said. She pointed out that a padded luff will allow the sail to be furled to 70-percent of its original size and will still sail well to weather. This 30-percent furl yields a jib that is 87.5 percent the area of the fore-triangle. It can be furled to any appropriate size for off-wind work.

Hasse said that the Catalinas 125-percent, roller-furling genoa (375 square feet) will offer steerage in flat water in about 5 knots of wind and perform optimally between 8 and 18 knots. It should be partially furled/reefed to its working jib size (260 square feet) for winds from 20 to 30 knots. The genoas tack should clear the bow pulpit, and its clew should be about six feet above the deck. This clew height can perform well on all points of sail while allowing visibility forward, eliminating chafe and shape distortion at the bow pulpit, and a maintaining a clew height that works well with a pole and can still be reached from the deck for tightening the leach line or changing sheets.

Hasse was firm about additional headsails for light air and heavy weather. She recommended a storm jib and two light-air sails, a drifter and an asymmetric spinnaker. An inner stay is optimal for setting a proper hanked-on storm jib, she said, and she suggested a retractable Solent stay for this-ideally set about one foot abaft and parallel to the headstay, terminating aloft a foot or two below the masthead. A Solent stay does not require running backstays, and when rigged, it buys back the original foretriangle, allowing all manner of hanked-on headsails to be set, from storm jibs to drifters.

Hasse pointed out that a drifter hanked onto the Solent stay is both more weatherly and more manageable than a free-flying drifter. It can be set wing-and-wing with the genoa poled out to one side of the boat, leading the drifter sheet through a block on the mainsail boom once the boom is eased and prevented on the other side. A single-line furling system allows the drifter to be partially furled when deep reaching or running. She pointed out that this is useful when sailing wing-and-wing with the roller-furling genoa-both the genoa and drifter can be made smaller as winds increase.

Finally, Hasse suggested an asymmetric spinnaker for very light winds. An asymmetric spinnaker is a fabulous sail for winds from 3 to 12 knots, from a 50- to 150-degree apparent wind angle. I do not recommend a spinnaker furler.

Neil Pryde Sails

Bob Pattison started his sailmaking career in 1975, learning the art of sailmaking from a variety of sailmakers around southern California. This included working for Westsail, making around-the-world cruising sails for the familiar heavy-displacement cruising boats and later heading up a production loft for Prindle catamarans. Today, he heads Design and Special Projects for Neil Pryde Sails. His work for Neil Pryde includes the day-to-day design of sails and all technical matters pertaining to sails, as well as marketing duties.

Pattison pointed out that the Catalina 36, like most of the production boats of its era, was designed with a fairly high-aspect (narrow/tall) mainsail and a large, overlapping genoa (usually 150 to 155 percent of the J measurement). But in the intervening 25 years or so, the paradigm has changed a bit-so that even though the boat remains the same, sail technology and sail-handling systems have evolved.

Pattison wanted to know more about the owners and their home waters. Is it Long Island Sound, traditionally light air in mid-summer, or is it nearby Buzzards Bay, where you should expect breezes more in the 15- to 18-knot range? he asked. Do they sail as a couple (shorthanded) or normally have a few more hands on deck? How able and inclined are they to winch in the last two feet of the 155-percent genoa? These questions help us get the right genoa built for the boat and the crew.

He said a good rule of thumb for cruising is to have the fewest number of sails that cover the broadest range of conditions. His suggestion for our hypothetical Catalina 36 was a 140-percent genoa that must perform over the broadest range possible. The challenge, he explained, is to build a sail that is designed for 2.5 inches of headstay sag in 10 knots of wind but will still keep its original design shape when it has 50-percent more sag as the wind builds into the teens.

According to Pattison, contemporary fabrics, construction techniques, and sail engineering-along with a foam luff system-now make such a sail possible. With a good foam luff system, he said, the sail can be made smaller and flatter as it is furled, which will reduce heeling and maintain lift.

Pattison is a big fan of removable stays such as the Solent stay. It gives the sailmaker the luxury of building a few purpose-built sails-for example, a heavy-air jib or even a storm jib that can be fit to an inner forestay. In his view, however, our hypothetical couple did not need to splurge on this upgrade yet. Their single, all-purpose genoa is going to fit their needs for some time to come, he said. We can re-evaluate this down the road, should they decide to head offshore.

UK Sailmakers

Charles Butch Ulmer, son of the UK Sailmakers founder and an avid sailor who helped build the company into an international brand, wanted to clarify the rig dimensions, a critical step for any sailmaker. Ulmer gave the dimensions he used: I = 44.75, J = 14.33; P = 39.0, and E = 12.0. He pointed out that rig dimensions can vary among boats of the same model, especially boats like the Catalina with long production runs. This is another good reason to work with a local sailmaker who can come out and measure your boat.

Ulmer said the genoa size depends a lot on the geographic home of the boat. For the light air of Long Island Sound, Chesapeake Bay, or Southern California, it would likely be 150 percent. Outside the Sound or the bay (Newport, Buzzards Bay, Great South Bay, the Jersey Shore for instance), he said, hed reduce the size to a 135-percent genoa. He said the owners could push the size of the sail up, if they opted for a laminate material that uses high-modulus yarns such as Kevlar or carbon. Shape retention can be almost as important as size when it comes to how your sail performs in a breeze.

A working jib is a vital part of a cruising boat inventory, Ulmer said. He explained how the force generated by a sail varies linearly with area but exponentially with wind strength (apparent wind velocity squared). As a result, most boats get overpowered when the wind climbs into the high teens. This is when a properly cut working jib will make sailing much more enjoyable, he said. The boat sails faster, is more comfortable (less heel), and the sail is much easier to tack and trim. Last but not least, the ease of handling makes the boat much safer.

Ulmer recommend UKs tape-drive sail, a laminated sail that fine tunes load-sharing with reinforcing fibers aligned with the load paths. (The silver version-a fiberglass-yarn reinforced laminate-is regarded as the most cost-effective.) He also reminds sailors with string-reinforced sails to furl them in the direction that keeps the reinforcing strings on the outer-facing side of the sail so the tapes remain in tension.

Ulmer prefers a spinnaker over a drifter. He described how a cruising asymmetrical chute often makes it possible for you to sail instead of turning on the engine. To me, the complete cruising inventory consists of a main with reefs, a light- to moderate-air genoa, a heavy-air jib, and a downwind sail (cruising chute). Four sails, and youre covered for just about everything, he said.

Conclusion

The pros we caucused felt that a roller-furling genoa (maximum size somewhere between 125- to 150- percent of LP) was the mainstay, if not the sole headsail, for our hypothetical Catalina 36 owners. Some opined that it was the only headsail needed for an inshore/daysailed Catalina 36. All of those surveyed, however, stressed that local weather conditions dictate the genoas size. Most agreed that when going to windward, you are at the upper limit of the reefed genoas usefulness in about 30 knots. Although it may not be essential, a working jib would be a sensible investment for anyone planning any offshore work or sailing in an area where higher winds are more common.

In light air-the time to reach for a nylon sail or the ignition key-our experts had a little more enthusiasm for a cruising asymmetric chute rather than a hank-on or free-flying drifter; however, PS editors tend to agree with Hasse, who endorses having both. As for adding a removable Solent stay or forestay, most agreed that this was something that could be put off until solid plans are made to voyage farther afield.

Opinions diverged some when it came to sail design and material choice. Some recommended a cross-cut sail made of premium woven Dacron; others suggested a laminate material and a radial cut. Going with a laminate-and still using polyester yarn-raises the cost about 25 percent. Opting for the more esoteric fibers-aramid, polyethylene, or carbon-that are favored by racers can double the price. The radial cut and polyester laminate option seems to be a sweet spot for contemporary designs, creating a sail thats much less prone to shape-destroying stretch. This is accomplished by better aligning reinforcing fibers with multiple load paths.

Most sailmakers point out that performance also means ease of handling, less heel, and more lift, not just speed through the water.

Of the five sailmakers included in this survey, Hasses Port Townsend Sails was the only one that constructed all of its sails in its own local loft. Hasses favored material is Challenge Marblehead, a premium woven Dacron. Her approach to sailmaking includes lots of reinforcement detail and a firm belief in the importance of ongoing interaction with customers.

Most of the industry has moved production offshore where labor rates are lower. Pattison, of offshore production-pioneer Neil Pryde Sails, stressed how local sail design and customer liaison can work seamlessly with manufacturing on the other side of the ocean.

He summed up his take on cruising sails, We think you gain about 80 percent of the net improvement found in laminate technology just by making the decision to go with a sail that is radial or string cut-even if it is just polyester.

The goal of all the pros we interviewed was to gain market share by satisfying customers. They all agreed that the key starting point is discovering how a client sails, whos on board, and what kind of plans they have for future voyages.

For a more comprehensive guide to sail-buying, including several articles on choosing a mainsail, see the online version of this article, which includes links to recent articles. Also, those reports, along with others on specific topics like storm sails, have been compiled into an excellent three-volume ebook that is available in our online bookstore.