Aboard a sailboat, pulling on, easing, and securing lines is what you do—a lot.

In Ye Olden Days, the belaying was done on square or round pinrails (a.k.a. fiferails) at the base of a mast or at a rail, in which were inserted a flock of belaying pins made of iron, bronze, or wood like teak or lignum vitae.

Lines, in very precise patterns, were affixed to the belaying pins, which had only to be withdrawn to free a line. It took some muscle if the line was heavily loaded, less if the pin was properly tallowed.

A belaying pin made a handy weapon; maybe that’s why Germans called it a Coffeinagel.

No one knows when bitts appeared. They probably first came in pairs, until somebody ran an athwartships pin through one.

Little is known either about horned cleats. Made initially of galvanized cast iron with the horns flared up a bit, they are seen on fairly old ships. A horn cleat with one horn is called an “arm cleat.” They were originally “two-holers,” as shown in the photo on page 12. Later, they were cast with holes for four fasteners, a distinct improvement because this spread the load and deterred them from chewing oblong holes in the deck. The “four-holers” usually are “open-base” cleats, which means you can (without much interfering with the basic function of the cleat), run a line through the opening and secure it with a figure-eight knot.

If there were a nautical book on how to belay a line, it might next deal with the jam cleat, which was an ingenious development that probably came about when somebody made a regular cleat that warped badly. A jam cleat can be dangerous because it can clasp the line so forcefully that it must be cut.

It was half a hundred years later that the Wizard of Bristol, Nathanael Herreshoff (the nautical world’s Leonardo da Vinci), invented the very graceful cleat that bears his name. It accommodates more line than a standard horned cleat. Unfortunately, in these days when apostasy is hot stuff, the Herreshoff cleat has become known as a “yacht cleat.”

In Europe, cleats often are made with two metal posts and a wood bar; they’re both handsome and utilitarian.

There are, of course, many “designer” cleats, usually intended for powerboats. They’re probably done by unemployable interior decorators. One truly loathsome version is shown in that photo on page 12.

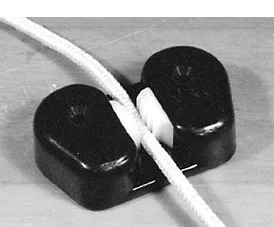

Our hypothetical book, The History of Belaying, might next deal with a series of improvements on devices to belay a line. These include clam cleats, sheet stoppers, lance cleats, and rope clutches, some examples of which are shown in the accompanying photos. And, before some alert reader nails us, there’s that sensational line-belaying device called the self-tailing winch.

The Persistent Cam Cleat

Most enduring of all these modern line-holding devices is the cam cleat, which is the subject of this Practical Sailor report.

The cam cleat has persisted because it’s a marvelously simple gift from the field of mechanical engineering. We know not who invented the cam, which facilitated eccentric circular movement, but it enjoys an almost perfect application in the cam cleat.

Cam cleats are useful in many applications—halyards, sheets, guys, lifts, travelers, vangs—almost any place where a control line must be frequently adjusted.

The cam cleat made its debut about halfway through the last century. Used primarily in those early days on one-design racing boats like Thistles, Lightnings, Flying Scots, Snipes, and all of the ever-changing Olympic-class boats, the early versions frequently slipped and the too-sharp cam teeth chewed voraciously on any line. Improvements followed steadily. Today, cruising boat owners, shorthanded or fully crewed, use them for all sorts of purposes, and of course they’re standard for a myriad of small control lines on racing boats.

The cam cleat is extraordinarily simple to use, but has limitations that must not be ignored. Most have impressive safe working loads, but there can be a problem in freeing a heavily loaded line. The Lewmar marine catalog puts it clearly; on every page showing a cam cleat is a warning that says the cleat is “…designed to hold only the load that can be applied manually.”

Sailors flout that warning, often on small boats with jib or main sheets that can be handled in light to medium air, but need in heavy air a quick, little luff to jerk loose the sheet. It’s not fast for the boat, and it is, in fact, dangerous, but it’s done.

In more perilous situations, you’d better have a knife close at hand.

There are many manufacturers of cam cleats. They’re simple to make. In fact, one version shown in the photos is made of just three pieces of molded plastic. As with horned cleats, they can be made of stainless steel, bronze, aluminum, nylon, or any of the new plastic composites.

The field is somewhat dominated by Harken, Ronstan and Schaefer, but also in the race now, meaning that they offer a wide range of cam cleats, are Barton, Holt Allen, and RWO. Lewmar makes a limited range. The Servo, a clever German cleat, is not often seen in the US; a Servo cleat called a “Spring” is used on some of the new Wichard sailing hardware.

The Various Tests

There’s no point in testing the breaking strength of these devices. Practical Sailor found that out in 1992 when we strength-tested 16 cleats and found the best easily withstood a 1,000-lb linear pull, without slipping. That’s far beyond what will happen on your boat—or what ought to happen, unless you’re harboring a fearless and house-broken gorilla. An important part of the testing were observations of the ease of operation—both securing and freeing the line.

The cam cleats that worked toward the top of the test procedures (those that held 1,000 lbs and were easiest to operate) were the Harken Cam-Matic 150, a big Holt-Allen, Ronstan’s RF 5010, and a big stainless steel Schaefer. Ronstan’s then-new C-Cleats earned Best Buy designations. Other makers represented were Nicro, Servo, Nashmarine, Barton, RWO, Saylor, and Tuphblox.

A month or two later, PS conceded that it had missed a cleat. Although a Nashmarine Synchro-Grip was included, a Nash Trigger Cleat was not. Both were invented by Douglas B. Nash. The Nash Trigger has a clever pull-down release mechanism. When tested, it took 1,000 lbs, didn’t slip, and could be released by hand up to 220 lbs. It was rated with the above-mentioned “best.”

With the explosion of line-holding devices—cams, clams, lance cleats, stoppers, V-cleats, rope clutches, etc.—Practical Sailor, using its famed Doomsday Chafing Machine, undertook in 1997 to test them all for line abrasion. Obtained for that test were new samples of 11 cam cleats from the 1992 tests. The line used was New England Rope’s popular Sta-Set.

The 1,000-cyle test indicated that the British-made Clamcleats and Ronstan’s then-new V-Cleat created less line wear than cam cleats. The best cam cleats were Harken’s then-new Carbo-Cam and Ronstan’s C-Cleat.

So What’s New?

Cam cleats now are offered not only in metal versions, but also made from powerful plastics. They’re far more evident in the chandlery chains then they were even a few years ago. Part of that may be due to their snazzy packaging; part is certainly due to pricing of the plastic models, and part is that they’ve been proven successful and relatively safe on the water. They’re also faster and easier to use than standard horned cleats, especially for greenhorns. (Note well that PS isn’t advocating the wholesale replacement of critical horned cleats on board—cams are great, but only in spots carefully analyzed for loads, both constant and shock, and for the potentially dangerous release by errant foot or elbow.)

What’s new is that the “Big Three”—Harken, Ronstan and Schaefer—are being pursued by other manufacturers, each of whom offers a full line of cam cleats.

The relatively new horses in the race, all British, are the venerable old hardware maker, Barton; Holt-Allen, another old-line firm started by a small-boat racer named Jack Holt, who was a contemporary of Tom Mix; and RWO, another small- boat hardware specialist that is pushing into big-boat gear and commercial applications. (Many makers of marine hardware and rope have, in recent years, ventured forth into the big, lucrative industrial and architectural fields.)

Also in hot pursuit of the line-holding business is yet another English company, Spinlock, makers of the powerhouse ZS Jammer, a rope clutch that will hold eight tons. Spinlock, which has a very active design team headed by Chris Hill, replaced last February its smaller and very successful XA clutch with a model called the XAS, which will handle any line from 4 mm to 12 mm.

Pertinent to this story is the fact that Spinlock in 1999 gave up cam cleats and introduced its PX Powercleat. The PX can be released under heavy tension by lifting up on the line (mind your fingers!). The Nash Trigger Cleat mentioned above releases with a downward pull. The Spinlock PX (reviewed in Practical Sailor’s March 2000 issue) and the Nash Trigger Cleat, now made and marketed by Harken, have similar but not exactly the same mechanisms.

Conclusions

As pointed out earlier, strength testing has been abandoned because, while testing a dozen new cam cleats and the new Spinlock PX (using 1,000 cycles of cleating and uncleating) there were no failures at pull tensions far greater than stated safe working loads—loads that also are beyond what can be exerted by any human other than those lumpy-looking gents in TV’s Stongest Man shows.

Line abrasion is another matter. Most of the cams that make these cleats work have been improved, usually by having their grip “softened.” Taking a lesson from earlier empirical efforts expended by those who went before, cam cleat makers in the last several years have introduced models with blunter, more line-lenient teeth.

Although the differences are not in a magnitude that should deter a buyer from selecting any cleat that suits purpose, space, and wallet, the latest round of 1,000-cycle tests give the highest marks, for the least abrasion, to Harken’s Carbo-Cam, Ronstan’s C-Cleat, Spinlock’s PX Powercleat, and RWO’s new Carbocleat, with its shallow cams and “progressive” teeth.

So far, there’s nothing quite so handy as a cam cleat for tweaking a moderately loaded line with minimum nisus.

But remember—just as the oldtime sailor’s feet were at risk when he pulled the belaying pin, one’s fingers can be in danger when snapping a taut line out of a cam cleat, especially one that has an integral fairlead. Match the cleat to the anticipated load, and make sure you have a mechanical means to relieve that load when it goes over your muscular threshold.

Contacts— Barton, Imtra, 30 Samuel Barnet Blvd., New Bedford, MA 02745, 508/995-7000, www.bartonmarine.com/. Harken, 1251 E. Wisconsin, Pewaukee, WI 53072, 262/691-3320, www.harken.com/. Holt-Allen, 177 Lynden Rd., Lynden ON L0R 1TO, 888/390-3242, www.holtallen.co.uk/. Lewmar, 351 New Whitfield, Guilford, CT 06437, 203/458-6200. Ronstan, 7600 Bryan Dairy Rd., Largo, FL 33777, 727/545-1911, www.ronstan.com/. RWO USA, 1025 Parkway Industrial Park, Buford, GA., 770/945-0564, www.rwo-usa.com/. Schaefer, 158 Duchaine, New Bedford, MA 02745-1293, 508/995-4882, www.schaefermarine.com/. Servo (handled by RWO), Alexander-Roberts, 1851 Langley, Irvine, CA 92614, 949/250-1253. Spinlock, Spinlock USA/Maritime Supply, 12 Plains Rd., Essex, CT 06426, 860/767-0468.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Veteran Cams and New Cams Behind the Blocks.”