As a family on a sailboat traveling on the Great Loop, our crew of four aboard Fika was a bit out of the ordinary. While not a common sight, many sailboats do take on the Great Loop adventure. The first question we’re asked when folks learn about our vessel is, “Don’t you have to take the mast down?”

America’s Great Loop is a waterway adventure that will lead you on a circumnavigation of the eastern portion of the United States. When the first “Looper,” Kenneth Ransom, and his crew of teens made the trip in a sailing yawl in 1898, he didn’t have a modern convenience that stood in his way: fixed-height bridges.

Two areas along the Great Loop are restricted by your vessel’s air draft: New York along the Erie Canal (a modern marvel in its early days that allowed for more accessible settlements in the Midwest) and just south of Chicago in the Illinois River.

As you approach the Erie Canal, three routes have varying height restrictions. A 21-ft. air draft lets you take the Erie Canal and the Oswego Canal to Lake Ontario. A 17-ft. clearance enables you to take the “triangle loop” into Lake Champlain and the St. Lawrence Seaway to Lake Ontario. A 15-ft. height gives you the option of the entire Erie Canal to Lake Erie. No matter the route, the mast must come down when traveling by sailboat.

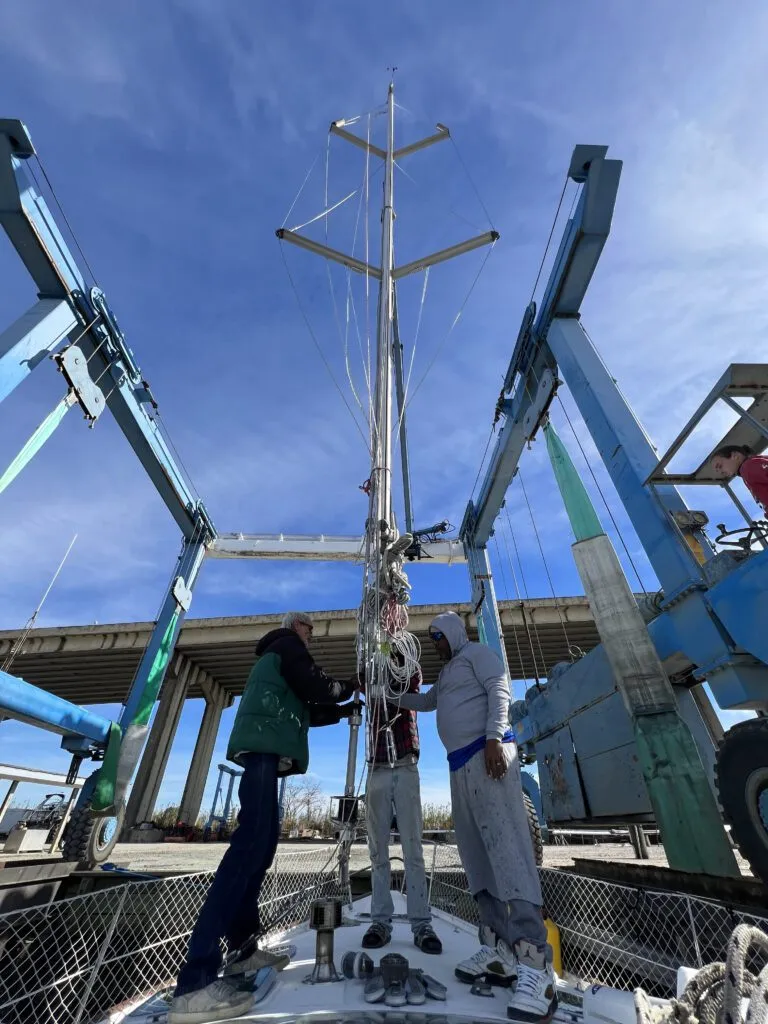

As our family sailed and motored up the Hudson River in early July 2023, we aimed for Hop O’Nose Marina in the Great Northern Catskills. The marina wasn’t a polished resort; it had a few amenities, but its primary feature was the marina crew’s skill. However, the old rusty crane for our mast lowering raised our eyebrows slightly.

“This crane was used in the original construction of the Erie Canal!” we were told. Did they mean all the way back in the early 1800s? From the looks of the crane, this fact was very plausible.

The marina crew was skilled in the task; it was evident that this was a common stop for sailboats coming from and going to the canal for mast raising and lowering. We planned to travel with our mast on our deck for this stretch of the Loop. The Hop O’Nose team quickly constructed mast supports for us from 2×4’s and provided us with straps to secure the mast. One support was near our bow, the other in our cockpit directly in front of the helm. The process of demasting, the cradle supplies, and the labor to help build the cradle and set the mast in place brought us to about $800.

The primary negatives of carrying our mast on deck were that our visibility was more limited, our deck and cockpit were crowded, and we lost some maneuverability for managing our lines while locking through the canal. We were also top-heavy in a way that the boat wasn’t intended for, making it precarious if we were waked hard by faster vessels. Additionally, we were now a longer vessel for any dockage that might be charged by the foot (our mast length exceeded our hull length).

Despite these inconveniences, we enjoyed transiting the Erie Canal with no significant issues. We opted to travel the entire length of the Erie Canal, as it served not only an interesting history curriculum as we learned about its origin and impact in the many canal-side towns we visited, but the western half of the canal, often missed by many Loopers, was peaceful and beautiful. Our lowest fixed bridge to pass under was 15-ft. 6-in. shortly after Oneida Lake, but we easily cleared it with our mastless air draft of 13-ft.

After cruising the canal for 19 days, we reached its terminus in Tonawanda, NY, just north of Buffalo, where we’d enter Lake Erie. We found our way to Wardell Boat Yard, where we refueled and had their assistance raising the mast for about $600.

After we looked like a sailboat again, we wanted to ensure our rigging was in good shape, as we planned to sail quite a bit in the Great Lakes. We replaced our outhaul and tuned the rig for about $1,000 at RCR Yachts Buffalo Marina.

After sailing across Lake Erie, up Lake Huron, under the Mackinac Bridge, and into our home cruising grounds in Lake Michigan, we approached Chicago to continue our journey south through the river system. Just south of Chicago is a fixed bridge, and all vessels must pass under it to access the lower rivers; there is no other way. This bridge has a clearance of 19-ft. 6-in. along the Illinois River.

In mid-October, we took Fika to Crowley’s Yacht Yard Lakeside on the Calumet River to take down our mast. The crew’s cost to safely remove and pack our mast for shipment to Mobile, AL, was about $1,225. The river system would take us longer to transit than the Erie Canal, so we opted to have our deck clear for this portion of the route rather than working around our massive mast on the deck.

From there, Crowley’s helped us work with Cross Country Boat Transport to ship our mast to Turner Marine in Mobile, AL. The cost of transport was about $1,400. Our vessel’s equipment would be loaded onto a truck bed with other masts, shipped to Mobile, and await our arrival there.

The lack of mast weight onboard changed our vessel’s dynamics (our boat weighed less and sat higher in the water) as we traveled as a funny-looking motorboat along the rivers. Still, the freedom on our decks and unobstructed visibility were worth it. Not only could we see directly in front of us without cradles in the way, but we also had an open deck without any rigging, making it more straightforward to tend our lines in the massive locks along the river.

In mid-December, 56 days after removing our mast, we could put it back up at Turner Marine, located at the mouth of Dog River and Mobile Bay. One drawback of shipping the stick is that you can no longer control or protect the mast while it travels south without you. We found minor damage on our mast once we raised it. However, it’s not worth pointing fingers, as it could have happened during any stage, from removing the mast, shipping, and putting it back up. For $638, Turner Marine accepted our mast from the shipping company, held it for us, and stepped it back onto Fika once we arrived.

To ensure our safety and efficiency, we had Stanley’s Services Sailboat Rigging Specialists come out while we were at Turner Marine. These folks are professional, thoughtful, and wonderful to work with, and their prices were very reasonable. The rig inspection, rig tuning, and rigger aloft cost us $350. They also performed additional services, replacements, and fixes. At the same time, they worked with us based on their recommendations and our needs, taking time to confirm we understood their notes and guidance for future maintenance.

As a sailboat, we are often given a hard time (usually in jest) for the added cost of removing and shipping the mast multiple times during our Great Loop journey. The prices I outlined above add up to just over $6,000. However, compared to fuel costs of reasonably fuel-efficient and cost-conscious trawlers of about $10,000 on fuel alone (though more often they are spending $20,000 or more), our own low fuel consumption and given our love of sailing whenever we can (even in the Intracoastal Waterway!), we wouldn’t hesitate to encourage sailors to take on America’s Great Loop in their sailboat if that’s the way they love to cruise.

For the benefit of those who would like to save a few dollars on mast stepping/lowering, the Castleton Boat Club on the Hudson River at Castleton on Hudson, about 16 miles south of Waterford, is much less expensive. Current rates for the do it yourself service using the mast crane are $100 for the first mast and $50 for a second. There is dockage available as well as moorings.

The usual routine here is that you assist the guy in front of you, and the guy behind you helps you – then everyone retires to the clubhouse for an inexpensive beer. The last time I went through, the club commodore assisted me in stepping my mast – and bought me a beer when we were done.

On the other end, I would strongly recommend RCR over Wardells for your mast, or if you’re continuing on into Ontario, use Sugarloaf Marina in Port Colborne at a cost of $6.40 (Canadian) per mast foot. Just be sure to pick a calm day for the crossing as you don’t want your mast to topple over into the drink.

In Oswego, I used Oswego Marina. Very professional, and I had a good experience.