In our ongoing study of ways to compare, and hopefully improve the way our anchors set, weve learned that it takes time and slow, delayed setting to make best advantage of very soft mud. However, firm sand and weeds can have the opposite character-making it hard for the anchor to penetrate.

Engineless boats and even those with auxiliary outboards may lack the power to drive the anchor home during setting. Just as Chesapeake lore has long held that soaking the anchor was the solution to soft mud, engineless boaters have long known that the momentum of the boat could provide good penetration when needed. Of course, like a surveyor with a phenolic hammer, tapping during a survey, you need to know how hard to strike.

When performing qualitative tests of dinghy anchors in the shallows, our tester Drew Frye occasionally found he needed more tension than a steady pull could deliver, so he wrapped the rope around his hips, reset his feet, and really leaned on it, bouncing hard. If the rode was chain, the anchor either came loose or simply slid horizontally without penetrating. If the bottom was mud, the anchor would pull loose. In both cases, the force was applied for too little time and the force was too great for the anchor. However, if the rode was nylon and the bottom was sand or firm mud, the dynamic load was spread over several seconds and the anchor dug deeper.

It appears that the stretch of the rope both buffered the force and extended the time, allowing the anchor to break suction and move a few inches. Frye confirmed that anchors set in this manner penetrate just as deep and performed the same as anchors set by slow and steady application of force using a winch. The latter replicates the typical method of setting an anchor, backing down with the engine at a low to moderate and then eventually a full RPM.

Using this steady application of thrust, most boats equipped with an inboard engine can test their anchors holding ability up to about 40 knots of wind load, assuming that the anchor employs a long snubber to absorb some of the load. Based on our testing, 1 horsepower inboard puts the equivalent of only about 22 pounds of force on the anchor in reverse, so a boat equipped with a 28 horsepower engine can put about 600 pounds of setting force on an anchor. This is about the same anchor loads that 35-foot sailboat can expect in about 42 knots of wind.

However, if the boat is equipped with an outboard, the anchor can only be power set and tested to about 20-25 knots, not enough to fully bury an anchor in a firm bottom. Frye hypothesized that in these cases you could use the momentum of the boat and the shock absorbing capability of the rode and snubber to achieve a deeper set.

The key, he discovered, is to use the stretch of the line to convert the boats momentum into a sustained force (not an abrupt shock load). It is similar to the method used to pull a stuck vehicle out of the mud or a snow bank with a nylon rescue strap. It is important to note that without this elastic component in place you will only break out the anchor (or possibly break something on the boat). Be warned also that even when using a properly-sized snubber, you will likely cause your anchor to drag in a soft mud bottom (See Anchoring in Squishy Bottoms, PS February 2015.). On the good side, this intentional dragging will give you a clearer indication of how poor the holding is in that location.

How We Tested

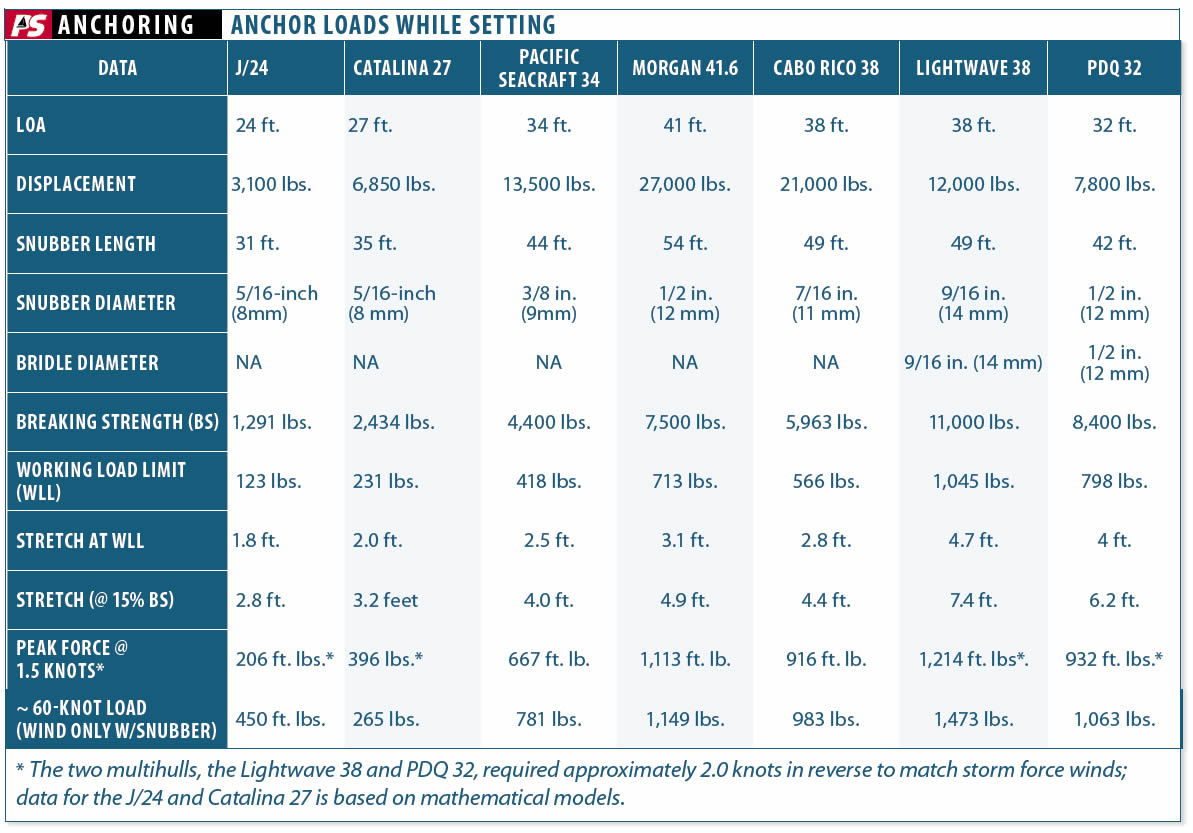

We took the same PDQ 32 catamaran used to test anchors and snubbers over the past few years, and anchored in the very consistent firm sand of a favorite test location. Scope was fixed at 7:1, the depth was 6 to 7 feet, the anchor was a 35-pound Manson Supreme, and rode was grade 43 chain with one of two different snubbers. We backed down on the anchor at speeds of 1-3 knots, recording force with a load cell, and diving on the anchor to observe setting behavior. We also plugged the essential data (boat mass, speed, and snubber length, strength, and elasticity) into a model we developed for snubber sizing, to see if the calculations matched reality.

Observations

By coincidence, the snubber designs presented in What is the Ideal Snubber Size? (Practical Sailor, March 2016) handle both surging in a storm and the stored momentum of backing down against the anchor at up to 1.5 knots (2.5 knots for multihulls) in equivalent fashion. The amount of kinetic energy gained by the yacht equals the energy absorption capacity of the snubber/rode combination, and the peak rode tension is about the working load limit of the snubber.

Even if setting force is limited by an anemic outboard to an equivalent of 25-30 knots of wind, you can set and test an anchor to about 60 knots in good sand by backing down firmly against it 2-3 times. The key is to maintain the peak force on the anchor for several seconds-long enough to get the anchor moving and keep it moving for several inches. Any greater speed needlessly increases the risk of over-straining ground tackle or loosening the anchor.

Our mathematical model fit the field data within statistical limits (about 10 percent margin for error), allowing us to estimate the bump setting forces for a range of boats, confirming that these speeds will be both safe and equivalent to real world forces, so long as the specified snubber design is used.

Physically, the anchor achieved a set exactly the same as we observe with the slow-and-steady engine setting. When the Manson was set under engine power alone (275 pounds), the roll bar was about half exposed and the shank buried along with a few feet of chain. By the time we increased to speed to 2.5 knots, the roll bar was fully buried, along with the shank and 6-8 feet of chain. The anchor had moved about 30 inches, suggested a normal digging angle.

The breakout to setting force ratio was normal for this anchor in this soil, further confirming normal setting behavior. This observation applies to fine, firm sand and mud only. It does not apply to soft mud or in light, coarse coral sand.

What about combination rodes, where most of the length is nylon? If only 30 to 50 feet of nylon is deployed after the chain leader, you can expect similar results to our all-chain-plus-snubber performance. If you use more than 100 feet of nylon, consider increasing the speed by 1/2-knot to attain the same force, although because the force will be applied over a longer time period, the force does not need to be as strong.

What about weeds? So far the results have been mixed. In some cases, a bump is just the thing to help the anchor cut through surface roots. In other cases, all we did was pull out a chunk of root mat. In our view, sailors should try hard to avoid weeds-both because of the environmental impact and poor anchoring.

Keep in mind, that this technique only applies to convex fluke scoop anchors and Danforth-style, hinged fluke anchors. Plow and claw anchors require slower setting action. When bumped, plow anchors tend to churn up the bottom which can impact setting. Claw anchors are more variable-if they have rolled into the setting position, bumping is effective, but if they are on their side, they will drag.

Conclusion

Although sailors have been using a similar technique since the age of sail, it is unfamiliar territory for many contemporary recreational sailors. Based on our repeated tests and observations we are confident using it with our own boats, but every boat is different.

Wed recommend trying both methods in a clear anchorage where you can observe the anchor set before adopting it wholesale. Sailboats with auxiliary inboards shouldnt ever have to resort to this technique. If you can’t get a good set using slow-and-steady application of engine force, then you should try to find better holding ground.

This approach is most effective with a nylon rode, although a long snubber with a chain road. is acceptable. It is not appropriate for chain rodes with short snubbers. The forces are considerable, over a ton in some cases, so rig carefully and do not exceed the recommended speeds; more is not better.

Based on field tests from our anchor snubber test and mathematical models derived during a range of other anchor tests, assuming a boat has properly sized ground tackle and snubber (only necessary when using a chain-only rode) to absorb shock loads, a reverse velocity of about 1.5 knots delivers peak forces that approximate those of a 60-knot gust. The model does not take into account the effects of the sea, which can be significant in exposed anchorages.

Dear Darrell

I would very much appreciate your thoughts on a hybrid solution that I have started using on my 40 foot sailing boat. Perhaps I could give an example of how we anchored this summer in a difficult situation.

I laid 35 m of chain when we were anchored in a depth of about 10 m and then attached the chain hook which was on 8 strand nylon. I then let out a further 5 m taking the chain hook three or 4 m below the surface, through the bow roller, and attached the nylon to a cleat, but not a cleat near the bow, but all the way back to a mooring cleat at the stern. Using this technique I was able to deploy about 18 m of nylon without increasing the swing of the boat. I’m aware that many people use nylon’s snubbers, but generally they seem to attach the snubbing line to a cleat on the bow. I can’t see any disadvantages of my system and it puzzles me that no one else seems to use such a set up. I would very much appreciate your comments on this idea.

Kind regards

Ashley Royston