Sea anchors are as old as seafaring. Sailors through the ages have carried buckets, bags, cones—just about everything except the kitchen sink—and thrown them over when they wanted to limit drift. Where the water is too deep for anchoring to the ground sea anchors have long had their uses. Drogues, too, have a long history. Whether as “drags” used to tire harpooned whales or “brakes” to control hard-to-maneuver barges, drogues have been working the waterways for centuries.

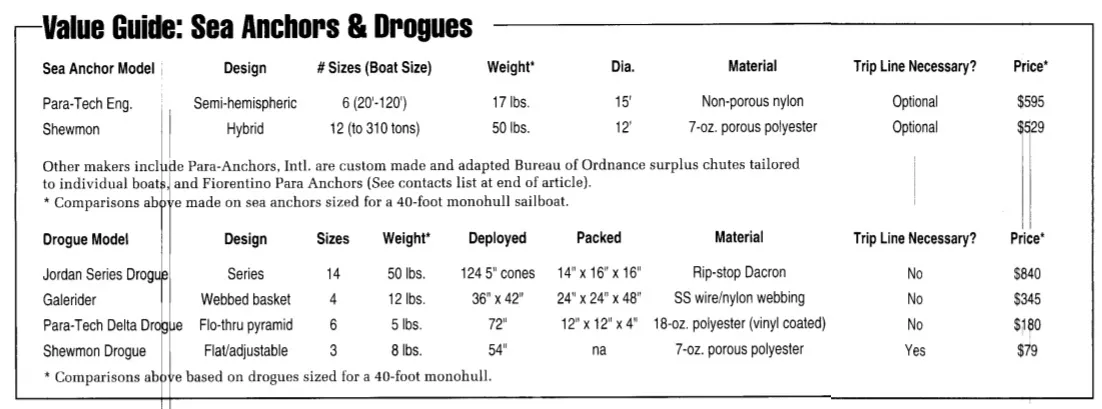

Our examination of commercially available devices is not a product comparison but an overview of some available options.

Definitions

There’s understandable confusion between sea anchors and drogues. A sea anchor is meant to fix a boat in place, much like a conventional (non-floating) anchor. A drogue, on the other hand, generally goes over the stern. You use it to control speed and stabilize your course as you run downwind away from the seas.

Both sea anchors and drogues work by creating drag. Both are ways of keeping your boat end-on to the wind and seas. However, their heavy weather missions are quite different.

Sea Anchors

The main reason sea anchors and drogues get confused is that, until relatively recently, they were basically the same thing. What John Claus Voss (author of the turn-of-the century classic Venturesome Voyages) and even Adlard Coles in his Heavy Weather Sailing called “sea anchors” were small conical devices much like present-day drogues. However, dating roughly from the end of Word War II, sailors and, most particularly, commercial fishermen, began experimenting with parachutes as devices for heaving to. Patrick Royce was the first sailor to tell of these adventures (early 60’s). John and Joan Casanova subsequently (70’s and 80’s) made well-documented use of a parachute anchor in their multihull cruising. Lin and Larry Pardey (aboard the monohull Seraffyn) used ordnance chutes to heave to and wrote about it.

Para-anchors have come into their own; large-diameter devices on the parachute model (or, as in the case of the modern Shewmon anchors, designed from scratch) have evolved in the past 20 years to offer infinitely more “holding” power than the time-honored cones. The sea anchors available in the US today (from Para-Tech Engineering, Para-Anchors International, Fiorentino Para Anchor, and Shewmon Inc., among others), plus those few available on the international market from Para-Anchors Australia and Coppins, Ltd. (New Zealand) all have the size and strength to do what the older devices couldn’t—”stop” the boat from drifting and hold its bow to weather.

Your sea anchor allows you to stop, to attend to a problem, make repairs, get a rest. If the wind and waves are moderate, “anchoring” your boat in open water is relatively simple and straightforward. If it’s too deep to drop the hook, the sea anchor lets you “park.”

Most sailors, however, look to sea anchors to help them handle heavy weather. And in robust blows and gale force winds para-anchors have earned high marks. They have proven that they can bring the boat end-on to the waves and limit drift (often to as little as half a knot). Testimonials are impressive. For example:

Windswept (Hinckley Bermuda 40 yawl) deployed a 12′ Para-Tech sea anchor during passage of a frontal trough (winds 35-40 knots) off the coast of Maine. The skipper recounted thusly:

“After deployment my yawl lay bow-to the wind and waves with very little yawing. With 400 feet of rode there was absolutely no shock loading. My boat rode like a duck, up and over each wave, always nose to the wind. Altogether a very pleasant, safe, and secure feeling.”

That happy, cozy result is what sailors are looking for. Shewmon advises, “Set the anchor at the first sign of heavy weather, BEFORE the deck gets wet and it’s hard to work. Then go inside and catch up on your rest.” The parachute sea anchor is often painted as the “last, best solution” for the weather-whipped sailor.

But it’s dangerous to regard the sea anchor as a “set-it-and-forget-it” solution to heavy weather. Once crests form on the waves, things change. Water now moves laterally, not up and down. It moves at wave speed (up to 25 knots) and can have an impact of one ton per square foot. That changes the game. Breaking waves slew boats off course, roll them over, rocket them out of control. Breaking waves usher in survival conditions.

It’s a comfort that not many storms produce breaking waves. Still, when they do, they introduce significant problems if you’re riding to a sea anchor. The first is yawing.

Other Aids For Staying Bow To

How your boat rides to a ground anchor is a good guide as to how she will ride to a sea anchor. Multihulls, for instance, ride relatively straight to both ground and sea anchors when they bridle the anchor from both bows. A monohull, on the other hand, streams a sea anchor from a single fixed point. That increases yaw.

One antidote is a riding sail. A sail set well aft (even a storm jib hanked to the backstay and sheeted flat) will help a boat stay head-to-wind. If you are able to, reduce windage forward (roller furlers are classic culprits) you can do a lot to keep yourself effectively bow-on.

Another remedy is the form of heaving to popularized by the Pardeys. They ride, with or without sail, to a sea anchor, but they attach a control line to the rode and bridle it to their quarter. By adjusting the control they can “winch the stern to weather” and bring their bow off the wind. The hull makes some leeway which in turn generates a “slick” that helps dampen wave action on their weather side. It’s a promising variation to riding bow-on.

Even if you eliminate yaw, you are left to deal with the effect of powerfully breaking wave crests. Thrown aft against an anchor “fixed” in the water, your boat can conceivably generate a pull approaching its own displacement. The tactic here is to position your anchor so that it is in phase with the boat, cresting when the boat does. You don’t want the anchor to be “fixed.” Maximum scope goes a long way toward achieving the “in-rhythm” balance that can keep loads on the boat and road within reason. Para-Tech recommends a minimum of 300′ of rode (or 12 times the boat’s length overall, whichever is greater). Both Shewmon and Para-Tech insist on nylon rodes because nylon’s elasticity limits shock loads.

“We used to think that we could set a sea anchor with the gear that was already aboard for ground tackle. I’ve learned that you need to have gear designed especially to do the job, in terms of strength, efficiency, and chafe prevention,” said Earl Hinz, author of Understanding Sea Anchors & Drogues. Wind loads alone can push the pull on a rode to more than a ton. Para-Tech specifies 1/2″ nylon for boats up to 35′, 5/8″ for boats from 35′-45′, and 3/4″ rode for boats up to 55′. A dedicated strong point, one that doesn’t rely on deck cleats or skimpily backed windlasses, seems almost mandatory for handling a sea anchor.

Chafe is also a problem. There are reports of systems that chafed through “within hours.” Hinz inserts lengths of chain at 100′ intervals in his rode and lets the chain handle abrasion. Repositioning chafing gear on a bar-taut rode from a wave-swept foredeck is difficult, at best. You can’t do much once you’ve set the anchor. That makes adjusting rode length virtually impossible beyond “freshening the nip” by easing it a couple of inches every hour or so. Shewmon’s answer: “Assume the worst case scenario and stream all of the rode permanently protected from chafe at the boat end from the start.”

Pre-planning helps, but practicing is the best preparation for setting your sea anchor in a storm.

Boats riding to a sea anchor will make some sternway. The more severe the motion astern the more grave the threat to the steering system. A rudder hinged on the keel or transom might even be forced against its pintles and sheared off. To counter the backdowns induced by wind and wave, lock the rudder amidships. Lash the wheel rather than relying on the friction brake. Better yet, mount your emergency tiller and lash it.

Riding to a sea anchor more or less rules out adopting any other heavy weather tactic. That’s mostly because getting going again involves either cutting the gear loose or trying to wrestle it back aboard.

Trip lines are standard items with both Para-Tech and Shewmon sea anchors. The Pardeys and many others don’t use them, though. They fear they might snag and sabotage the system. Hinz favors a partial trip line (about one-third the rode’s length) with its own buoy. Even when you succeed in imploding the chute via a retrieval line, you still have retrieval to contend with. In moderating conditions you may power up gradually along the rode and get away with as little as 15 or 20 minutes of intense line handling. If the waves remain and things are anything but perfect, however “retrieval is harder than you can imagine” (according to author and cruising instructor John Neal. As another sailor put it, “It’s like trying to reel in a giant squid from 20,000 fathoms down.”

Sizing a Sea Anchor

Choosing a sea anchor begins with the size of your boat. Shewmon explains that his anchors function at their rated diameter “while the Para-Tech anchors are flat. That means that they curve when they fill with water so their working diameter is 30% less than their rated diameter.”

For example, a 6′ Para-Tech sea anchor equals the holding power of a Shewmon sea anchor only 4′ diameter, he said. Shewmon’s sizing guide suggests a 10.5′-diameter meter chute for a 35′ boat and a 13.5′ device for a 45-footer. Recommendations for Para-Tech equivalents are 16′ (for a 35-footer) and 20′ (for a 45-footer), respectively.

US Sailing’s Recommendations for Offshore Sailing puts forth a general guideline—sea anchor diameter should be approximately equal to one-third of a boat’s length overall. Says Victor Shane, a maker of para anchors as well as the author of the Drag Device Data Base, “Err on the larger side for safety, much as you would with ground tackle.” Fears of tethering to “immovable objects” have occasionally led sailors to fit their boats with under-sized chutes. Says Walter Greene of the 4′ Shewmon streamed from his 50′ catamaran Sebago, “I thought anything bigger would be too unyielding.” The boat survived 48 hours of 50-knot winds in mid-Atlantic, but her bows sheared off at 45°-60° throughout the storm.

The bigger the sea anchor the bigger the challenge involved in deploying and retrieving it. Getting it over the side is essentially a matter of preparation and technique. Set the chute to weather (to minimize chances of its sliding beneath the hull), “sneak” it directly into the water to keep it from blowing about, have the rode properly led, flaked and snubbed, and pay off under control (sail or power). Tension on the rode should open the chute. Given the elasticity in the system and the required (considerable, to say the least) scope, the shock of fetching up against it should be minor and not break anything.

Drogues

Tests conducted by the American Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers have proven that a boat running before waves is likely to broach when waves approach a height equivalent to 35% of its waterline length. Steadied by a drogue, however, a boat will withstand waves as high as 55% of waterline length. And there are other virtues to towing a drogue.

Most often boats lose control running off before heavy weather because they are going too fast. Leaping off the top of one wave into the back of the one in front will, sooner or later, present problems. Calming your pace so that you stop short of pitchpoling, get a grip on broaching, and put a stop to pounding can be a simple matter of towing a drogue. Most of those available have shown that they can cut top speeds in half.

Drogues do more than that to help steering control. By holding the stern into the waves they limit yaw. By adjusting the drogue so that it pulls on your weather quarter you create an “anti-broaching” force. You can rig a bridle from the stern and use it to “pull the stern around” or lead the bridle to strong points forward of your rudder so that you can “tow the drogue around” with positive control.

“Drogues,” said Shewmon, “are for fair weather. Once waves start to break you want to deploy a sea anchor.”

It’s true that none of the drogues on the market today can “save the day” on its own the way a sea anchor might. Tethering to a sea anchor is primarily passive. You don’t trim sail, dodge waves, or do much more than monitor the situation. Running off is a more active approach. Boat type, sea room, crew reserves, storm avoidance, damage control…the factors that go into choosing which tactic to take are legion and complex. Drogues offer no absolute guarantees against pitchpoling, broaching, or capsize—but they do help the boat stayl end-on to the waves (running off). Keeping that choice open makes them valuable in heavy weather.

The drogues inherited from whalers and cod fishermen suited sailors well for a while. But boats got faster, loads got bigger, and a few flaws began to surface. Time-honored cones and the variations thereon tended to porpoise, swerve, oscillate and pulse as water flow increased. For good speed and steering control you need a steady pull. A new generation of drogues developed almost entirely since the Fastnet storm of 1979 now provides it.

Galerider. Developed by sailmaker Ed Raymond along with yachtsman Frank Snyder, this open-weave basket of webbing gets its pull from a small disc of heavy vinyl in the basket’s bottom. Shewmon’s tug tests (and testimonials from a number of sailors) indicate that it pulls straight with no tendency to yaw. Galeriders come in six sizes (from 18″ diameter to 48″) and have been described by sailors who have towed them as strong, durable, consistent, and simple to deploy and retrieve. John Neal favors it.

Seabrake GP-24. Evolved by Australian commercial fisherman John Abernethy, Seabrakes are based on variable flow. On the original solid Seabrake a baffle prevented most water from passing through it, making it provide tension enough for moderate steering and speed control. Increased water flow from increased speed opened the baffle to create turbulent water flow. That increased drag by as much as 70%. The successor drogue (GP-24) has a “staged system” of variable resistance to produce similar performance in a lighter device made from cloth. Seabrakes have been in use for 15 years and found favor with Down Under racers (like Sir Peter Blake) and cruisers in both multihulls and monohulls. They have limited availability in the US.

Attenborough Sea Drogue. Developed in the UK and used there by lifeboats and fishermen as well as sailors, this 25-lb. solid stainless steel weldment contains a series of angled vanes. As speed increases, flow over the vanes accelerates. That causes the device to dive deeper and “pull harder.” By adjusting the vanes to a shallower dive angle you can use the Sea Drogue for steering control alone. Stowage and retrieval of the solid unit present problems. It has yet to be marketed worldwide.

Shewmon Seamless Drogue. Sold in three sizes (27″, 54″, and 106″ widths) these drogues are made from single pieces of cloth. Shewmon has tug-tested the largest up to 9,000 lbs. of pull. Pull varies with the square of speed (tripling speed produces nine times the pull). Additional speed control can be achieved by adjusting the trip line and “shrinking” the drogue. However, as Shewmon warns, “Readers are advised to abandon all thoughts of partial tripping unless they are willing to spend considerable time and patience experimenting.”

Para-Tech Delta Drogue. Due to tri-corner exhaust vents, increased flow through this drogue produces increased drag, thus suiting the load to the conditions. Guide surface design promotes stability and the water flow helps assure that the drogue will retain its shape. Available for boats from 25′ to 80′ in length, the device comes in six sizes. Made from heavy, vinyl-coated fabric, the Delta stows easily and is relatively easy to retrieve.

Jordan Series Drogue. Towed from the stern like a conventional drogue, this device attempts to do the job of a sea anchor by aggressively holding the boat end-on into the seas. Donald Jordan, its inventor, is a veteran of the aircraft industry and former MIT professor. Jordan’s answer is a series drogue, a rode arrayed with a series of small cones and stretched downward and aft by a weight. Depending on the size of the boat, 90 or more 5″ cones are spliced in line to a 300′ tow line at 20″ intervals. Jordan said that an average (25,000-pound) boat will need about 130 cones.

Sailors who have used Jordan’s drogue say that it works well.

“It slowed our speed to between 0 and 1/4 knot. Yaw was only 5° either side of heading,” reported Gary Danielson of using the device aboard his 25′ monohull in 25-30 knots. The problem that arises, however, is that the boat’s stern quarters tend to be held where they are vulnerable to assault from waves.

Jordan counters, “The approaching water mass is essentially wedge-shaped. In most cases a breaking wave slides under the stern and lifts it rather than smashing down on it.”

“I disagree,” said Steve Dashew, circumnavigator and author of the new book, Surviving The Storm (order at www.setsail.com), who supplied photos for this article. “You can’t discount the impact of a breaking wave. Some boats are well-protected aft, perhaps with center cockpits, but many others, with exposed cockpits, lockers, and companionways are vulnerable. The wisdom of riding stern-to the storm thus depends almost entirely on the type of boat that you have.”

Recommendation—Sea Anchors

You might get an inexpensive conical device or prospect the offerings of such far-flung para-anchor purveyors as Coppins, Ltd. (New Zealand) or Para-Anchors Australia. However, after reading hundreds of case histories and talking to sailors and manufacturers we have found little or nothing to justify taking your sea anchor search that far afield. Design and construction of the basic parachute varies somewhat, but the track records, accessibility, and commitment of the two proven and accessible American manufacturers—Para-Tech Engineering and Shewmon, Inc.—make them ones you may wish to consider.

Dan Whilldin, Para-Tech president, is a veteran of more than 30 years of working with parachutes, both for aircraft and for boats. Feedback from the sailors who have used his sea anchors was a big factor in developing the deployable stowage bag that lets you set your Para-Tech by simply dropping the bag (with rode attached) overboard. To us this appears a significant advantage and one that sets Para-Tech apart from Shewmon, whose larger canopies need to be rolled and stopped with twine to ready them for use. Coupled with a significant weight difference (Para-Tech = 17 lbs., Shewmon = 50 lbs.) for comparable sea anchors, Para-Tech is the easier of the two to set.

Shewmon sea anchors are heavily built. A mining engineer and inventor, Dan Shewmon made his own sea anchors for his cruising motorsailer, then went on, in 1978, to found Shewmon, Inc., which now makes and sells a variety of anchors and drogues also of his own design. An anchor for the average (35′-40′) monohull is made from 7-oz. knitted, slightly porous Dacron cloth. “Water is non-compressible and 853 times heavier than air,” he argues. “Common sense dictates that sea anchor cloth should be considerably heavier than parachute cloth.”

Para-Tech employs zero-porosity, high tensile (approximately 2-oz.) nylon in its canopies. Shewmon’s Dacron is undoubtedly stronger. But Para-Tech’s nylon has proven (in Dan Shewmon’s own tug tests) that it can survive loads greater than those seen in recommended use. Further, more than 30 reports in Victor Shane’s Drag Device Data Base tell of setting Para-Tech anchors in winds up to 85 knots, seas over 25 feet, and for as long as 53 hours. Only one account mentions cloth failure: two “well-frayed holes between vent and skirt were found upon retrieval, but there’s no doubt the anchor saved the boat,” said skipper Stephen Edwards of Adelaide, Australia.

Shewmon argues that the porosity of his cloth stabilizes the canopy. Para-Tech points to the resiliency nylon cloth gives to its anchors, better enabling them to absorb loads. There are also significant design differences. Shewmon has created a hybrid of conical and flat shapes with a deeply scalloped (rather than dimpled à la a parachute) circumference. Para-Tech chutes, modeled closely on the standard BU ORD drop chute, depend on a swivel in the system. Shewmon contends that swivels aren’t reliable and that he has “designed out” oscillation.

Pulling power?

Says one chute deployer, “Despite my para-anchor being clearly undersized by manufacturer recommendations, it held us like a brick wall (in winds of 35 knots and 20-foot seas).”

Yawing and oscillation?

Neither are reported as problems in Shane’s Drag Device Data Base.

Commendable as Shewmon’s durability appears and as persuasive as his arguments may be against swivels, we don’t see how the Shewmon differences translate into improved sea anchor performance. Both systems are equally cranky and awkward to retrieve. Making a choice then shifts to the last variable—ease of deployment—for which the Para-Tech seems to have the edge.

Recommendation—Drogues

The Jordan Series Drogue is in a class by itself. Much more of a sea anchor than a true drogue, it fixes a boat end-on to the wind and waves with a resilient efficiency that wins praise from all quarters. Your boat has to be designed and built to survive seas stern-on, however, before the JSD becomes a good option.

The Galerider and Delta are simple to use. They deploy without fuss, create high drag at relatively low loads, and pull with a firm steadiness that makes them ideal for steering control. Both rely on swivels. The recommended use of a length of chain to hold the Delta below the surface adds, we feel, unwanted complexity. Galerider’s open-flow design seems less-likely to become unbalanced than the tri-corner system seen in Delta. Galerider costs, however, nearly twice what Delta does.

The Shewmon Seamless Drogue offers the fascinating potential of controllable drag and incorporates the ingenuity of an egg-weighted lower side and a hole-vented upper lip to promote stability and “grip.” These elements make it more complex, however. Given the consistent and effective performance of its simpler competitors, it seems to us that the Shewmon drogue (made from a single piece of cloth and therefore seamless) may take more adjustment and getting used to than the others. But, at $79 (54″ model) it is only half the price of its nearest competitor. That might make it a worthwhile experiment.

Experience at sea has shown the GP-24 (and the solid state Seabrake from which it evolved) to be effective, but these Australian-made devices are hard to get in the US. The solid Attenborough Sea Drogue from the UK is cumbersome to stow. Also, sea trials indicate that deployment is not a simple matter.

Because drogues are more versatile, adjustable, and easier to use than sea anchors, any of the ones we examined might be useful. Because it combines value, function, and proven performance, our selection is the Delta drogue.

Contacts- Attenborough Sea Drogues, (Dr. Neil Attenborough), Fallowfield House, Puttenham, Guildford, Surrey GU3 1AH UK; (44) 1483-300366, fax (44) 1483-34496. Fiorentino Para Anchor, 1048 Irvine Ave. #489, Newport Beach, CA 92660; 800/777-0732; www.paraanchor.com. Galerider, Hathaway, Reiser & Raymond, 184 Sellect St., Stamford, CT 06902; 203/424-9581; www.hathaway.com. Jordan Series Drogue, Ace Sailmaker, Hellier’s Yacht Sales, 128 Howard St., New London, CT 06320; 860/443-5556; www.acesails.com. Para-Anchor International, (Victor Shane), PO Box 19, Summerland, CA 93067; 805/966-9782; fax 805/966-7510. Para-Tech Engineering, 2117 Horseshoe Trail, Silt, CO 81652; 970/876-0558; www.seaanchor.com. Seabrake International, (John Abernethy), RFD (Australia), 3/7 Kent Rd., Mascot, Sydney, NSW 2020, Australia; (61) 29-667-0480, fax (61) 29-693-1242. Shewmon, 1000 Harbor Lake Dr., Safety Harbor, FL 34695; 727/447-0091.

The link to the Sea Anchors and Drogues Value Guide is broken. I would like to look at that guide. Can the link be fixed or the guide emailed to me? Thanks!

Thanks for the article. Very informing. I have a Fraser 36 . It has a high , possibly ” Clipper ” bow with a lot of reserve buoyancy. We have a rear cockpit and a traditional three board with a sliding main hatch . We tend to yawn quite a bit at anchor . The bow lifts very readily , maybe too readily, in steep choppy waves . I am wondering how these attributes would affect the choice between a drogue and a sea anchor . I would have gone with a drogue, if not for thought of sea breaking on our rear hatch .

The three washboard companionway problem can be solved by installing thick hinged Barn Doors on the outside of your washboards. Lockable from inside and out.

The Barn Doors provide increased impact resistance plus give you other (less fiddly) options when closing your companionway.

Barn Doors backed by your Washboards will keep you dry.