There was a time when headsail handling meant snapping on bronze piston-hanks and hauling on a smooth-running halyard. Times have changed, and now it’s all about how the furling drum rotates and the headsail wraps around a foil-covered headstay or freewheeling torque rope. Some systems behave more willingly than others, but all benefit from low-friction leads guiding the furling line back to the cockpit. The following report takes a close look at how these fairleads stack up and how much efficiency they add to the furling process.

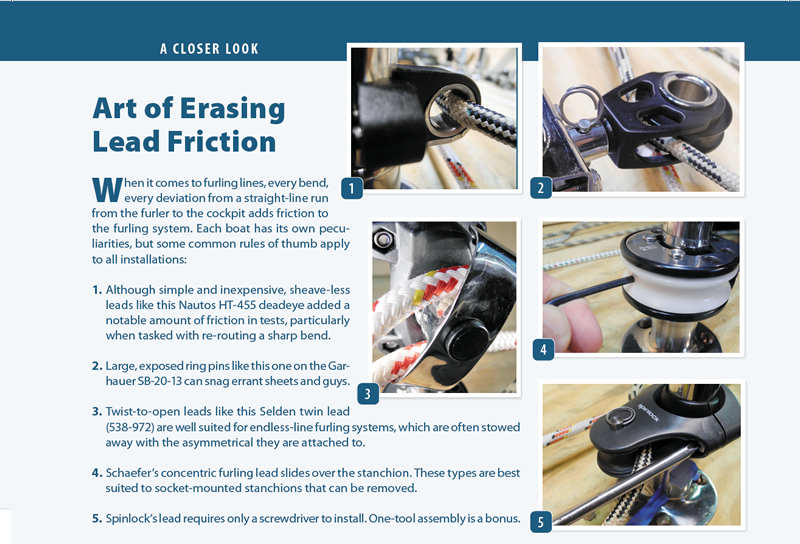

Every bend and change of direction in a line requires a fairlead or block, and some amount of friction is added at each deflection, increasing the total tension it takes to furl the sail. Interestingly, the ideal number of routing blocks is none; a straight run with no line deflection generates zero friction. But few deck designs and hardware layouts allow for a straight and direct line lead.

On most boats, the furling line is shunted outboard along the stanchions in order to keep the decks uncluttered. Because routing along the stanchions defies the rule of straight-line efficiency, it makes sense to minimize the friction through the use of low-drag blocks for furling-line fairleads. Fortunately, the industry has responded to our headsail furling needs by designing and manufacturing a wide array of stanchion-mounted blocks that pivot, twist, and align with changing angles of pull.

The range of products dedicated for this purpose is surprising. Ultimately, we winnowed the field to 20 different furling line fairleads from six manufacturers. Our assumption going into this test was fairly straightforward: Friction caused by line deflection is an enemy to furling efficiency. Our search focused on finding the blocks that generated the least amount of friction, as measured on our now-familiar test jig , but we also looked at other elements that are critical to this function.

During the course of testing, it became clear that there are different segments of a line lead, each with specific challenges. No single fairlead fit all the demands of running a furling line from stem to stern. For example, the initial lead from the furling drum to the first fairlead involves multiple constraints. This block not only guides the line; but it keeps it spooling evenly and prevents it from chafing on the drum cover.

Following the all-important lead block is a set of routing fairleads. These keep the furling line following the curve of the lifeline stanchions. Finally, there is the last block, one that must smoothly redirect the furling line to a belay point (jammer, cleat, cam cleat, rope clutch) in the cockpit.

WHAT WE TESTED

Although you could make your own furling fairleads by pairing a set of specialized blocks or deadeyes with homemade Dyneema loops and shackles (see PS April 2015 online), this test is limited to pre-fabricated hardware that easily clamps to lifeline stanchions, requiring little time or effort to install.

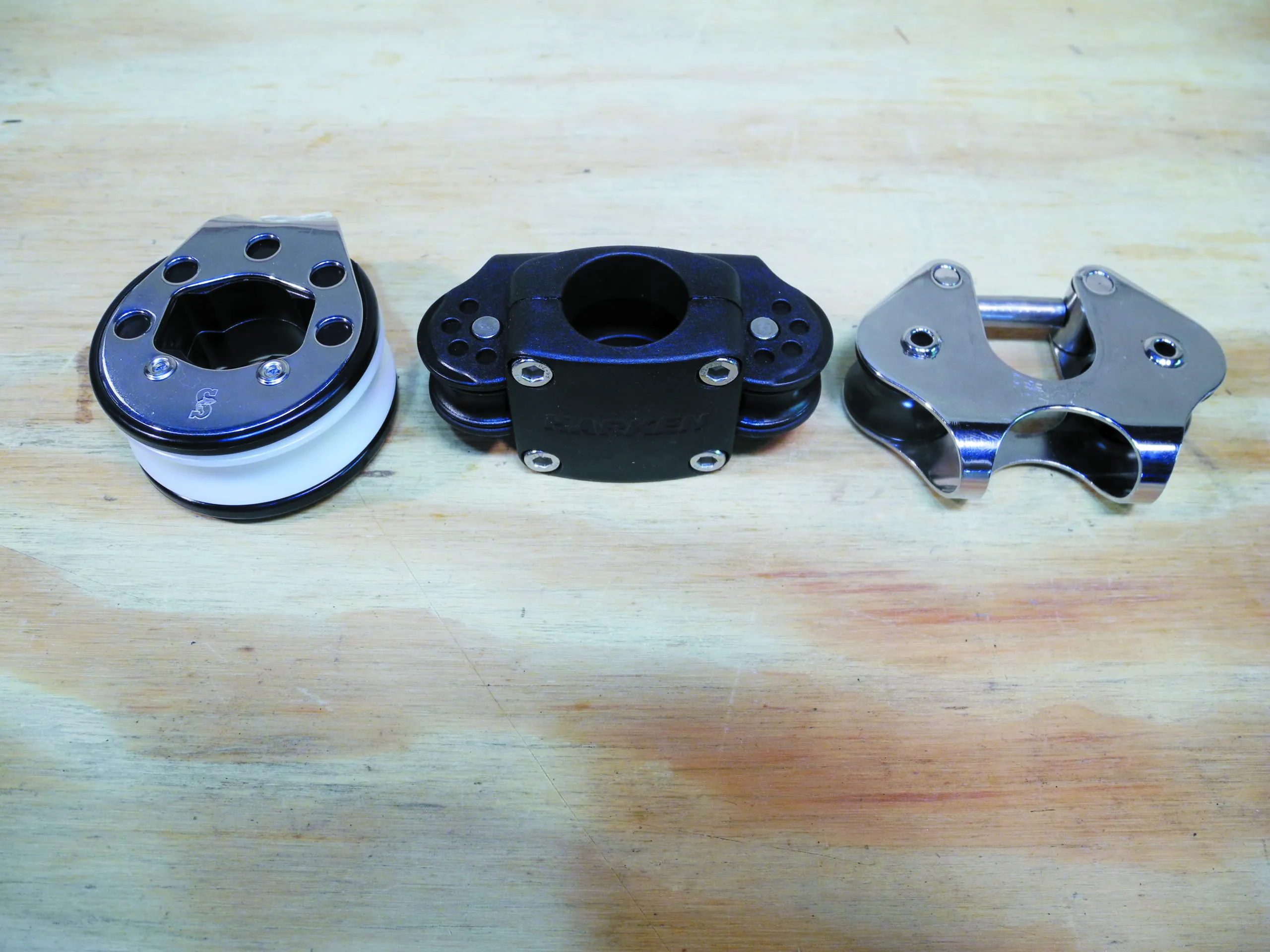

After some preliminary testing, it became clear that these fairleads fell into five specific categories, based on their purpose or design characteristics. Three sheaveless deadeye fairleads were put in one group; blocks that featured wide-angle, multi-axis articulation were put in another. Fixed, non-articulating blocks had their own category, as did single-axis blocks that articulated in only one plane. Three of the six manufacturers in the test sent a block that led the furling line outboard of the stanchions—these, too, had their own category.

Garhauer, a California-based company known for providing rugged, affordable sailing hardware, submitted four different products to test. Each one clearly reflected the company’s highly customizable, machine-shop approach to manufacturing. These mostly metal, clamp-on blocks feature highly polished stainless-steel and anodized aluminum shells and high molecular weight plastic bearings. Three of the Garhauer blocks were clamp-on designs, while one was a dual-sheave fairlead that slipped onto the stanchion, requiring that either the stanchion or the lifelines be removed.

Harken, a long-time leader in sailing hardware and a prominent player in the racing scene, provided several products, each offering an effective way to overcome furling-line friction. Its selection included a set of classic bullet blocks with stainless-steel shells reinforced with stainless-steel straps, a couple of 40-millimeter, lightweight Carbo blocks, and a larger 57-millimeter ratcheting lead block. Four of the five Harken fairleads were injection molded, a process in which nylon resin reinforced with glass fiber is thermo-molded to form the shell and clamp body. More and more products in the Harken lineup are constructed using this process.

Nautos, an international sailing hardware company with manufacturing facilities based in Brazil, also favors an injection-molded body. A clamshell-like clamping arrangement secures its blocks to the stanchions. The four products the company provided included three clamp-on block leads and one deadeye fairlead. As with Harken, Nautos’s largest swiveling lead block also had a ratchet function. The ratchet, which adds friction to the block when tension is applied in the direction of the drum, helps to reduce the load between pulls and adds some tension to the line as the sail unfurls.

Schaefer, an American company with a long history in the sailing hardware business, remains committed to stainless-steel blocks and clamps. Its blocks incorporate Delrin ball bearings and efficiently designed races to reduce friction. Ring pins and Nylock nuts ensure that fasteners don’t slip. Schaefers outside-the-stanchion clear-step fairlead block is designed to keep decks clear on smaller boats, or on cruising boats with narrow sidedecks that could quickly become cluttered if the lines were routed inboard. Its spring-supported lead block twists to align with challenging furling drum lead angles at the all-important first fairlead on the pulpit.

Selden, the Swedish spar maker has expanded into the hardware business and sent us four injection-molded, bushing-type, mini-sheave blocks that toggle in one plane. During installation, the owner carefully aligns the blocks according to the optimal furling line run. A set-screw then locks the angle in place. Selden also sent its quick-opening Double Fairlead designed for endless-line furlers. The lead is supposed to be paired with Seldens double cam-cleat, and presumably Selden’s endless-line furler, one of the higher-rated products in our endless furler line test. (See PS April 2011 and March 2008 online.) Selden also manufactures a deadeye lead and ratchet block that are worth looking at; we plan to test these for a followup report.

Spinlock, a British company best known for its line of high-performance cam cleats and rope clutches (see PS November 2014 online), manufactures two compact, lightweight stanchion-mount leads. The larger block incorporates a removable sheave to expedite use with endless-line furlers. It also can be tilted to adapt to minor offsets in lead angles. The smaller unit is an injection-molded, deadeye fairlead with a stainless-steel insert and a split clamp that attaches to the stanchion.

HOW WE TESTED

Our initial look focused on characteristics such as design, size, weight, and construction. The focus of our testing, however, was to accurately measure the friction each fairlead added to an evenly tensioned line.

The jig we used for testing was a variation of the jig we set up to measure friction in snatch blocks. (See PS August 2008 and August 2007 online.) Two large, smooth-running Garhauer snatch blocks were positioned opposite each other, and a continuous loop line was run between them. One block was fixed to a secure base, and the other was led to a Dillon dynamometer connected to an Ideal electric windlass. The windlass was used to tension the continuous loop running between the two blocks. After preliminary testing with line loads ranging from 50 to 500 pounds, testers settled on 200 pounds as the ideal tension for this test.

Testers then mounted a deck socket and lifeline stanchion to the test jig. The stanchion was set off to the side of the continuous loop, so that when the line was run through the fairlead being tested, the angle formed was 152 degrees (a close approximation of the angles formed in actual installations).

Before each test, testers tensioned the two, large ball-bearing snatch blocks to 200 pounds and used a spring scale to measure the force required to move the endless loop. This number, which varied between seven and eight pounds, became the baseline. For the test itself, the fairlead or block being evaluated was fixed on the stanchion and the loop was routed through it. Testers used the spring scale to measure the effort required to move the loop. We tested each block and deadeye fairlead five times. The highest and lowest scores were eliminated, and the middle three were used to determine an average.

In cases when a particular block design required slightly different mounting location on the stanchion (outside versus inside the stanchion, for example), testers could alter the position of the tension-inducing snatch block to ensure that the 152-degree offset angle remained consistent throughout the test.

We also took a close look at chafe points, the ruggedness of the clamp, and ease of inspection-particularly the ability to see how well the fasteners were attached.

The bench testing was supplemented with onboard real-world comparisons. This phase of the testing brought to light several key issues that were not readily apparent during our bench test.

Although our inspection of materials and construction offered insight into the durability of these fairleads, we did not fully explore longevity. A followup report will compare the long-term effects of weathering and exposure to ultra-violet rays, paying particular attention to corrosion resistance.

OBSERVATIONS

During onboard testing, we noted several different fairlead challenges. The first was at the bow, where the furling line leads from the roller drum to the first lead block. This location presented myriad alignment problems, and establishing the optimum lead angle and block twist at the pulpit was often frustrating.

The challenge of fitting the critical first fairlead, of course, will vary from boat to boat. In general, you want to position the lead block as close to the deck as possible; this reduces side loads on the furler and headstay. However, the height of the first block is usually determined by the position of the furling drum. The furling line should lead at a nearly perpendicular angle to the headstay (and thus the drum). In most cases, the first block is positioned on the pulpit rather than on the deck. In some instances, the first lead may have to be placed further aft on the deck.

Key attributes we look for in this first lead block are low friction, an ability to pivot in all planes, and an ability to swivel. A ratchet block can also be helpful here to grip the line between tugs and provide some resistance as the wind catches the sail and unfurls it. (See PS May 2009 online for our last test of ratchet blocks.)

The block used for the primary lead is often the right choice for the last turning point, where the furling line is redirected inboard toward a rope clutch, jammer, or cleat where it can be belayed in the cockpit. Swiveling, pivoting, and minimal friction are essential here, and if you are going to fit just one ratchet block, this is the most logical spot for that block.

Between the first and last blocks are several blocks that serve to maintain a fair lead and keep the decks clear. These tend to be fairly well aligned on a horizontal plane, but the vertical plane bows outward to follow the outline of the deck. Modern boats with narrow decks benefit from fixed leads that hold the furling line close to the stanchion, and many owners even consider investing in a set of outside-the-lifeline leads to keep narrow decks as clear as possible.

One of the key questions we had going into the test was how well the deadeyes, with their low-cost, easy-to-maintain design and no moving parts, compared to conventional blocks. The answer quickly became obvious: In terms of friction, blocks trump deadeyes every time—something sailors have recognized for centuries. In a no-load context, smooth surface, non-sheaved fairleads work just fine, but as soon as load increases, friction takes over and a deadeye delivers more grip than slip. When we finally tallied our test data, fairlead friction was three times greater when a line passed through a deadeye than when it passed over a sheave.

LEAD/END BLOCKS

When it comes to lead blocks best suited to handling the rope-to-drum challenge, we liked Garhauer’s robust stainless-steel, spring-supported, freely articulating SB-25 and Schaefer’s 300-35, an elegant, smaller, and lighter rendition of a stainless-steel furling fairlead.

While stainless steel is a sensible material for a furling block, we are not averse to composite construction. Harken’s composite 7401 proved to be a light and compact favorite. Its limited range of articulation may not be enough to suit all pulpit-to-drum geometry, but when it fits, its a star performer. Harken’s dual-sheave model, the 7405 was a double-barrel rendition of this Harken lead.

Nautos (92088) and Harken (7402) both sent us blocks that featured a useful ratchet option. Both are effective as either the lead or end-point block, and the ratcheting feature helps prevent the furling line from slipping between tugs.

Both designs are slightly hampered by the use of some square-wheel geometry. The circular sheave of a regular block is replaced by an octagonal-shaped sheave that improves the ratchets holding power, but getting the line over the miniature high spots takes just a little extra tugging-as our tension readings revealed.

Bottom line: When the tug of war was over, the Garhauer SB-25 earned our Best Choice for lead furling block. For the cockpit-end lead, we gave the Best Choice to Harken’s ratcheting 7402, which featured a secure four-fastener stanchion clamp and ball-joint articulation. It is more expensive, but in our view, it’s worth the extra cost. Our Budget Buy was the Nautos 92088, which added only minor friction but was significantly less expensive.

ARTICULATING BLOCKS

All of the blocks in this group adapt to some tilt or angle change, but their flexibility is limited. Spinlocks SPWL-2 utilizes an innovative axial ball-joint that centers on the stanchion, allowing the sheave to cant into alignment. There is no swivel function, so care must be taken to be sure that the range of tilt allows for a fair lead. This lightweight, small-sheave, bushing-type block (no roller or ball bearings) scored surprisingly well in friction testing—nearly as well as many of the ball-bearing-equipped blocks.

Two Nautos products that we tested, the HT-450A and the 92388, use the same two-bolt clamp. Each offers a single-plane tilting feature combined with a swivel function. These are well suited for stanchion-to-stanchion line guides. Both are bargain-priced, and the small-sheave bushing version (HT-450A) comes with a pull-pin to release the sheave. This feature, which lets you release the line from the block without threading back through it, could come in handy when trying to free a line that is hockled, knotted, or snagged. It will also benefit those who berth at a dock and like to stow the lines forward when alongside to reduce the trip hazard when boarding. The Nautos 92388 features a smooth-spinning, ball bearing race and is reinforced with stainless-steel straps.

The Selden 538-972 is an injection-molded composite lead that easily disassembles into its component parts. Its fiber-reinforced resin composite cage holds a plastic sheave that spins on a bronze shaft. It has a wide toggle range and an effective swivel action.

Bottom line: The Nautos HT-450A generated slightly more friction than the bearing-type blocks, but its attractive pricing and additional features, like swiveling ability and removable sheave, made it our Best Choice in this category.

LIMITED ARTICULATION

This category features four blocks that spin smoothly but offer even less articulation than the above group. They are best suited to the middle section of a furling line that lacks any sharp angles of deflection. Two standouts were the Harken 168NP and the Garhauer SB 20-13. Each of these blocks features efficient ball bearings, a stainless-steel stanchion clamp, a full swiveling body, and a fixed mount. The chief difference between them is in the mounting. The Harken uses a rubber bushing and ball socket to allow a bit of flex, and this gives it a slight advantage over the smooth-running Garhauer.

Our favorite in this group was the Schaefer 300-34, a no frills, fixed-mount fairlead (no tilt and no swivel) that is carefully engineered to reduce the intrusion of the furling lines on your side-deck. The compact, ball-bearing block mounts on the inboard side of the stanchion, but it achieves almost the same results as an outboard-mounted lead by keeping the furling line close to the stanchion.

Garhauer also sent us a double-sheave furling block, model D, which is designed to accommodate twin leads from an endless furling line. The fairlead offers two bushing surfaces and a central ball-bearing sheave. This design allows you to open the fairlead and quickly insert the endless furling line rather than feed it through each block, one at a time.

Ideally, this block should be located on the stanchion so that the sheave that handles the inhauling line, which imposes the most load on the block and stanchion, is below the outhauling line. Poor alignment of this block can cause the line to rub on the stainless-steel side plates or bushing surfaces, causing a significant increase in friction.

Bottom line: The Schaefer 300-34 was our Best Choice in this category; its especially well-suited for those looking to maximize sidedeck space.

DEADEYE FAIRLEADS

The term deadeye is ancient mariner speak for a fairlead that has no rolling sheave or other mechanical means of reducing fiction. Shape, smoothness, lubrication, and material choice are the key variables. The fact that there are no moving parts to break hardly makes up for the increase in friction such engineering delivers.

Spinlocks SPWL1 and the Nautos HT-455 both feature injection-molded parts with a stainless-steel sleeve. Split clamps are used for mounting. Both are nicely crafted, but the lighter, slightly more compact Spinlock keeps the furling line a little closer to the stanchion. More importantly, the curved inside surface of the Spinlocks line-lead ferrule imparted far less friction that the flatter inside surface of the Nautos. The more rugged clamp body and visible hex nut on the Nautos will appeal to cruisers, but the slipperier Spinlock was still the testers’ favorite in this group.

Selden’s easy-opening, twin-line guide is designed to accommodate lines led inboard of the stanchion. The Double Fairlead is not intended to be a lead or end block, only for the intermediate points. Interestingly, in our testing, it produced less friction and imparted less stress on the pivot spindle when mounted outboard.

Bottom line: We’re not big fans of deadeyes, even for this application. If you do prefer the simplicity of going bearing-less, the Spinlock SPWL1 earned our Best Choice for conventional furling line while Selden’s Double Fairlead earned a Recommended rating.

OUTSIDE-THE-STANCHION FAIRLEADS

Routing furling lines outboard of the stanchions can add more space to narrow, line-cluttered decks. Several hardware makers have blocks designed to surround a stanchion and lead lines outside just above well-secured bases.

Schaefers clear-step (506-44) is slipped over (or under) the stanchion and secured in place with a single set screw. The block’s large-radius hub and ball-bearing system delivers a superior, friction-free spin. Harken’s 7403 tandem sheave rendition clamps onto a stanchion without having to pull the stanchion from its socket or remove lifelines to install. Garhauer’s tandem, stainless-steel outside-the-stanchion lead can also be slotted right onto a stanchion and locked in place with just one cap screw.

Bottom line: It was tough to pick a winner in this group. All are in the $40 range and all scored well in our pull test. If you can pull your stanchions from their bases, or easily remove your lifelines, we like the Schaefer blocks. However, if the Schaefers are too much hassle for you to fit, either the Harken or Garhauer are a good choice for anyone looking to route their furling lines outboard. In the end, we picked the Harken 7403 as our Best Choice because of its slightly better friction rating.

CONCLUSION

We kicked off this round of testing with some preconceived notions—some held and some didn’t. The most obvious assumption that stuck was that blocks trump deadeye fairleads, especially as loads escalate. What fell apart was the idea that one specific fairlead should be used at all deflection points along the furling line run. In order to get the most efficiency and reliability out of your furling fairleads, you’ll want to select the specific type block for the specific job. Thus, we have our various categories, arranged by design and function.

Among the most important lessons we learned was to make sure stanchions are well secured—especially when fairleads and tension loads are well above deck level. Keep fairleads as low as possible in order to lessen the leverage associated with side loading. And finally, give extra thought to the line lead angles at the rope drum and where the reefing line is finally tensioned by hand or by using a winch.

The bottom line is that friction adds up, and stringing together a series of inefficient line-deflection hardware makes little sense. Keep in mind that a clear, straight run always delivers less drag than a deflected line running through the best of blocks. So when engineering a route for your furling lines, try to minimize the turning points. This is easier said than done, so the next best thing is to choose blocks that score well in tension testing, not simply sound like a roulette wheel when you spin them with your finger.

Our final task was to pick a block from each category to suit the needs of a crew aboard a 35- to 40-foot cruising sailboat. In some cases, there were several options in a near dead heat, but after considerable debate, here’s how the chips fell: The Garhauer SB-25 was our top articulating lead block; the ratcheting Harken 7402 was a favorite for the cockpit-end; the Nautos HT-450A was our favored limited articulating block (middle section); the Schaefer 300-34 was our favorite low-profile, inside-the-stanchion block; the Spinlock SPWL1 was our top deadeye-style block; and the Harken 7403 was our best product for use outside of the stanchion.

This article was first published September 17, 2015 and has been updated.

Nice article, but you only show solutions for 1″ post. That is useful for most; however, I have larger diameter and difficulty finding anything for 1.25″ posts other than the larger Schaefer blocks which unfortunately tend to deform when tightened sufficiently (there is only one set screw) creating resistance.

Well, I was hoping Myles would get a response. There are more vessels (including mine)now have 1.25”. As has been stated, there are not many options. Any response or assistance would be helpful

Regards, Cristian

“There was a time when headsail handling meant snapping on bronze piston-hanks and hauling on a smooth-running halyard” Well for me that is still how its done (adding a downhaul as well) and will stay that way for as long as my legs will allow me to go forward and change sails. Much prefer hank on sails and using the right headsail for the conditions then expecting one sail to do it all. If you think going forward to reef or change headsails is hard then try fixing a jammed rolling headsail or worse have all your sail unfurl on you in a blow and be unable to get it down because the halyard is now rapped around the forstay and it wont drop. Ill stick to hank on sails and a inventory or sails depending on conditions stowed below.

Yes I agree with Miles and Crisy stanchions around the Pulpit on My Tartan 4000 are 11/4 inch. I have yet to find a furling aid that is above one inch.