Most of us use one of two ways to keep a boat fixed in one place. We tie it to a dock, or we attach it to the bottom. In the first case, there’s often electricity and freshwater available, and maybe handy things like showers and a laundry; there’s usually easy access to the dock by car and an easy walk to the boat; and there’s good protection from standard wind and wave action. The main downsides are availability (in many locales, there are long waiting lists for slips) and high cost (supply and demand at work). Marinas are also sometimes not the best places to be in the event of a major storm.

In the second case, that of the permanent mooring, there are two main advantages the relatively low cost of equipment, and the ability of the boat to swing bow-on to the prevailing forces usually wind, but often tide. This greatly reduces a number of stresses on the boat, as well as the dangers of dings and gouges from pilings and poor boathandling on the part of one’s dockmates.

The main disadvantages are, first, the hassle of getting people and gear out to the boat, by dinghy or launch; second, the fact there are fewer and fewer places to plant a mooring; and third, the corrosive working of the elements upon that single slender tendril between bow and bottom.

There are many possibilities for the failure of permanent ground tackle systems, but the one PS is examining is chain failure. (Would we make a crack about weakest links here? Certainly not. Too obvious.)

Mooring Chain Background

Almost all chain used for permanent moorings is made of welded steel alloy, galvanized to forestall corrosion not, in the long run, to prevent it. The common hot-dip process involves, first “pickling” the raw welded chain in acid baths to clean it, then immersing it in molten zinc, which bonds metallurgically to the steel surface and forms a protective barrier. The zinc also acts as a sacrificial element against galvanic corrosion, an all-too-familiar process, especially in saltwater.

However, all is for nought. Entropy wins, as it always does, and mooring chain degrades, sometimes with amazing speed. There are several causes: galvanic corrosion from dissimilar metals, corrosion from stray electrical currents in the water, chemical corrosion, and simple abrasion from the chain links rubbing against one another.

According to Mike Muessel, owner of Oldport Marine in Rhode Island who has over 30 years of experience installing and maintaining moorings friction is the worst culprit in Newport Harbor, R.I. “It’s the wave action and the constant movement and rattling that creates the wear on the chain.”

John Doyle, national sales manager of Acco Chain and Lifting, says that chemical and galvanic corrosion are most worrisome from a chain-maker’s point of view.

Unlike bow-anchor chain rode that’s stored onboard, mooring chain is never regalvanized. It’s not worth it in most places it would need to be done yearly. Instead, it’s watched, and when nervousness overcomes frugality, it’s simply replaced.

Types of Mooring Chain

Most people use one of two types of chain for their moorings. Proof coil is the cheapest, if not necessarily the most economical. It’s made of a standard Grade 30 steel, and is hot-dip galvanized. It’s really a general-purpose chain many people use it for moorings because it does pretty well and they know it’ll have to be replaced regularly anyway. High-test is made of a higher-grade steel alloy (Grade 40), and special care is taken in the galvanization process. West Marine says the Acco high-test chain it sells is “shot-peened before galvanizing to create the longest-lasting protection against corrosion.”

High-test chain is said to be more abrasion-resistant than proof coil, and has a better strength-to-weight ratio. West Marine gives a two-year warranty for its Acco-made high-test chain against rusting.

Acco is the pre-eminent supplier of mooring chain to the recreational marine industry, partly by virtue of supplying most of West Marine’s galvanized chain, but also because the company is well-respected for its manufacture of mooring chain in particular (as distinct from the myriad other uses for chain in many industries). Their galvanization process is careful and costly, but effective at covering all cracks and crevices, according to Doyle. This initial resistance to corrosion is what makes the difference in terms of longevity in the marine environment. Acco also supplies Kellogg Marine (a major wholesaler) as well as other outlets that sell to professional mooring specialists.

Other domestic chain manufacturers include Campbell (Cooper Hand Tools), Columbus McKinnon Corp., and Chicago Hardware & Fixture. “We get our chain either from Kellogg or Lewis Marine and use Acco, Campbell, or Chicago,” says Muessel. “We’ve never found much difference in the American-made chain, but I’ve seen some bad foreign stuff.”

This is a common refrain among the pros: American-made chain is good, or at least predictable, while imported chain can be a hit-or-miss proposition. There’s a lot of imported chain on the market, but most is used for dry-land purposes like truck tie-downs and industrial applications. While all of the recreational marine outlets and wholesalers we researched stock American-made chain exclusively, there’s nothing to stop a consumer from walking into a hardware store or rigging supply shop and buying something off the shelf. Thus …

The Beginning of a Test

One of our editors lives in a particularly chain-hungry area of Long Island Sound, Conn. The bottom is thick mud, and any chain that rests in it is usually well-protected for four to five years, sometimes more. Upper chains, however those suspended in open water below mooring buoys have a short working life, usually two to three years. Muessel reports the same chain lifespan in Newport Harbor: “Three years, max.” We would suppose that freshwater mooring chains last a good deal longer, but would like to be set straight by freshwater readers.

We were curious to see how different types and brands of chain fared relative to each other. So we set up a simple test of seven different chains.

What We Are Testing

The chain being evaluated is shown in the chart above. All sections are 5 feet by 5/16 inches, give or take a couple of links. There are three made by Acco proof coil, high-test, and BBB, all from West Marine. Triple-B chain has shorter links than proof coil or high test, sized to work with windlasses, and is normally used as bow-anchor chain, not mooring chain. But we thought we’d have a look-see anyway.

After a certain amount of searching for an import, we obtained from a local wire and rigging shop a length of generic grade-30 proof-coil galvanized chain, convincingly marked “CHINA” every two feet. Interestingly, at a glance it looks exactly like Campbell galvanized proof coil. Compared to the Acco chains, these two have an elongated link hole, known as “pitch.”

Next, a length of gorgeous 316-grade all-stainless steel chain from Suncor, via West Marine. We included it because, despite its tremendous cost, 316 stainless chain is extremely corrosion-resistant, and does present a plausible solution for the upper section of a mooring, at least if you keep your boat in relatively shallow water. If you can deal with the initial outlay, and the chain lasts for a decade or so, you’re doing all right.

Finally, two chains from Campbell galvanized Grade-30 proof coil, and shiny zinc-plated proof coil. The latter is described as general-purpose chain, for logging and tie-down purposes, with no advice for or against mooring boats with it.

We weren’t sure we should include it, but when we were setting up the test rig, a neighbor who isn’t boat-afflicted came by and asked what we were up to. When we told her, she pointed at the shiny zinc-plated chain and said, “That’s obviously the best.” Instructive, no?

How We’re Testing

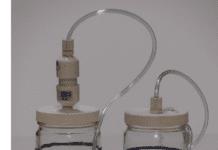

We put the five galvanized chains between doubled, painted two-by-fours. The top wooden piece has stainless eyebolts to hold the ends of the Campbell zinc-plated chain. The bottom wooden piece has a center eyebolt, to which is shackled a swivel, leading to the Suncor stainless steel chain, which is shackled (with a stainless shackle) to a 50-pound mushroom anchor. The galvanized chains (those most often used in moorings) were fixed in place with lashings and stopper knots rather than shackles, so as to minimize any influence from dissimilar metals. The top end of the rig was buoyed, and the bottom end anchored.

In early November, the whole thing was put into the waters of Long Island Sound, and there it now sits, awaiting a first look in late spring. Accounting for a 6-foot tidal range and plenty of current, the depth of the water should allow the central part of the rig to ride above the bottom, although the stainless chain will probably come in and out of the mud. We may leave the whole rig on the bottom for a couple of months when the ice comes in. We may move the whole thing in and out of the water periodically.

And a side test: Our local West Marine manager told us that a couple of his customers spray their mooring chains with Boeshield T-9, the waterproof rust and corrosion inhibitor developed by Boeing, with good effect. So we put two heavy coats of Boeshield on 1-foot segments in the middle of two of the chains. It will be interesting to see whether it makes a difference.

Stand by for the initial results this summer, after the chains have spent six or seven months in the water. Pending those results, if you need mooring chain, buy American!

Also With This Article

“Value Guide: Chains”

“Inspecting Your Mooring Chain”

Contacts

• Acco Chain & Lifting, 800/967-7222, http://www.accochain.com/

• Boeshield, 800/962-1732, http://www.boeshield.com/

• Campbell Chain, 919/781-7200, http://www.cooperhandtools.com/

• Suncor, 508/732-9191, http://www.suncorstainless.com/