The usual advice for anyone seeking all-rope anchor rode is usually to just get some three-strand nylon anchor. The makes sense. Three-strand nylon is inexpensive, wears best, and is easy to splice. But one size, or even one type of rope, does not necessarily fit all situations.

Some cruising sailors, including our intrepid technical editor, Drew Frye, incorporate some less common cordage materials into their ground tackle-such as Dyneema (see PS August 2018 High-tech Anchor Rode, ) and webbing (see PS December 2006 Quickline reel Takes the Snags Out of Storage).

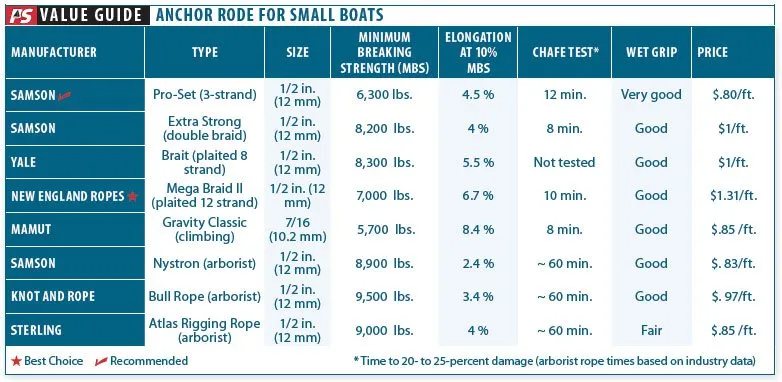

It could be that the material isn’t the issue, but the size, or the type. A common recommendation for anchor rode on small boats is 3/8-inch, which is the minimum size that a sailor can grip tightly. Although a larger diameter rode is easier to grip, its also more expensive. Can some of the other quantifiable benefits (like added chafe protection), justify spending more for a larger diameter rope?

And what about other weaves – like braided nylon, or eight-plate, or twelve-plait? In this report, well dig a little deeper into the options for anchoring boats in the 30-foot and under size range.

What We Tested

In the course of anchor testing and multiple boats, we used chain, nylon (twisted 3-strand, double-braid, 8- and 12-plait), climbing rope, polyester double braid, and 12-plait Dyneema. We noted user-friendliness, durability, and the effect on rode tension. They all have their place, but not on every boat.

We also tested rope diameters and weaves for relative grip. This was done by lifting anchors and pulling against load cells at equivalent effort, with gloves and without. Remember that 100-pound log we used in the chafe-testing pendulum? We got a lot of practice lifting it.

How We Tested

For testing, we used the same abrasion rig we used to test sewn eyes and rope (see adjacent article, How We Tested and PS September 2015, Slicing and Dicing Abrasion Data).

We tested each sample to failure, effectively condensing months or years of wear into just minutes. To compare elasticity we used the manufacturer-supplied data and results from our past tests , when available (see PS March 2016, What is the Ideal Snubber Size,). We’ve found most of the leading U.S. manufacturers-Yale, Samson, New England Ropes (Teufelburger), etc. – abide by industry standards and publish reliable load and performance data.

Observations

Grip. Since small boats typically lack a windlass, you’ll be hauling by hand. No one likes hauling on a slippery line that is too small. Material, texture, and diameter all play a role.

Weave. When pitting 3-strand vs. double braid vs. plaited (braided) rope, for rode, gross conformation can make a difference. The 3-strand and single braid ropes were more secure in the bare hand, with a slight edge going to 3-strand, though it depends on the brand.

Double braids (core-and-cover ropes) and climbing rope were less secure, although the difference was only about 10 percent and only noticeable when straining. Under light load they were more comfortable to handle, making it a wash. Line that was coated with Maxijacket or Ropedip was easier to grab, regardless of the weave.

Gloves. In addition to sailing gloves, we tried several types of coated gloves. While most sailing gloves reduce the risk of injury, they don’t improve your grip much. Rubber-coated gloves reduced the effort by about 50 percent. We keep a pair of Atlas Fit gloves in the locker for hauling messy rode, and in the winter we switch to coated freezer gloves. We also noticed that when wearing the gloves the differences between comfort and grip faded away (with the exception of Dyneema, which is always uncomfortable and hard to grip).

Stretch. Let’s start with the old saw about the necessity of maximum elasticity. If you were at the beach, trying to resist being tumbled to the beach by surf, would you prefer a rigid hand line, something with a little give, or a bungee cord that stretched so much you surfed with the wave before it caught? Something with a little give works best, absorbing the sting but generally holding you in position. Our testing of snubbers demonstrated great benefits of snubber lengths up to 30 feet, but the advantages diminished as length increased (see PS March 2016).

In separate testing for a future report, we observed that 40- to 100-feet in length appeared to be a sweet spot for nylon rode. Beyond that, more stretch meant more fore-aft surging at anchor, more momentum gained, more recoil, and a greater slack period that encourages sailing at anchor. This was particularly noticeable when we were using climbing rope, which is the same nylon woven for greater stretch.

Elasticity In Context

How much stretch is enough? First, let’s start by assuming you are at relatively long scope, at least 7:1 in non-breaking conditions. The depth is at least 4 times the wave height; if you are in the breakers, sorry, but you are in a tough spot.

The result of these two assumptions is that the wave height is always less than 4 percent of the length of the rode. We can’t see a good reason for the stretch to be more than that, unless you want to start surfing.

How does this compare to snubber testing? The most elastic rope we tested was a 35-foot climbing rope. In storm conditions, this snubber cycled between the working load limit (12 percent of breaking strength) and wind-only loads (4 percent of breaking strength), stretching to a maximum of about 3 feet. This snubber was attached to a high strength chain that also would extend about 1-2 feet under this load, as the last bit of catenary pulled straight.

Assuming 100 feet of rode are deployed, that results in 4 to 5-percent total stretch between the base wind load and combined wind and gust impacts.

Now, how does this compare with actual materials? Using the 4 percent of breaking strength benchmark, it looks like climbing rope is too elastic for the full rode. It also looks like 3-strand and plait have too much elasticity for this duty. However, if we use oversize ropes for manual handling on a smaller boat, stretch is reduced, and the bungee effect that a larger boat feels on conventionally-sized rope goes away.

We can also adjust the stretch to any setup by replacing a portion of the rope with something non-stretch, like chain, a covered Dyneema chafe leader, or a non-stretch bridle. We explored this last year (see PS August 2018 A High-Tech Anchor Rode).

Elasticity is of particular note in purpose-designed arborist cordage such as Sterling Atlas. The arborist industry always uses a polyester cover to withstand the horrendous wear and tear of ropes over bark and through the dirt, but for lines used to control the drop of limbs out of the canopy, a nylon core provides energy absorption. We’ve used these ropes both logging and in an industrial setting (good for fall protection), but we lack long experience with them on a boat. The stretch characteristics may be perfect for anchor line, neither too elastic nor to stiff, and with naturally superior abrasion resistance. However, they are stiff and don’t flake well, causing storage problems.

Chafe

Three-strand rope provides the best chafe resistance, with plaited ropes and double-braid coming in a close second. Climbing rope has a very tightly woven but relatively thin braid covering a parallel constructed core that is optimized for energy absorption.

Although the cover is very snag resistant, it typically makes up only 30-35 percent of the rope and is thus less durable than marine double braid, where the cover and core are roughly balanced. Arborist ropes have more wear resistance than any marine anchor rope, but we have not tested them in the field.

Secondary Rodes

A second anchor is often used exclusively for kedging (pulling the boat off a soft grounding or moving the boat with the engine) or to fore-aft anchoring. In both of these cases, less stretch is better. Although Dyneema will work and is very compact to store, most sailors prefer polyester for ease of handling and cleating, and because it has some stretch. Arborist rope is a great candidate for secondary rode, with stretch appropriate to both these roles and to use as a conventional rode in a V-tandem anchor system (see PS August 2016, Tandem Anchoring).

Nylon

The traditional anchoring workhorse, three-strand rode is economical, stubborn to knot or untie, and comfortable to grip with gloves on. Hard-lay ropes are strong, snag- and wear-resistant, more difficult to splice and hard to store. Soft lay is easy to splice, but is prone to snarling if flaked carelessly. We don’t recommend it for snubbers.

Never use a swivel with 3-strand rope-it will unlay under load and hockle unless both ends are secured against rotation. Coiling can be problematic. We tested Samson Pro-Set, which sells -inch diameter rode for $0.80/foot. We also have long experience with premium three-strand ropes from New England, Yale, and others.

Bottom line: Brand name, high-quality, three-strand line is our Best Choice for anchor rode.

Nylon Double Braid

Popular for its ease of handling, double-braid is more expensive and not as durable. Splicing requires special tools and skills, it wont splice directly to chain, and it does not work well in a windlass. It knots well, is less prone to tangling, and does not rotate under load.

We tested Samson Super Strong. We also have good experience with premium double-braids from New England and Yale.

Bottom line: Double braid is easy to handle, but wear is a problem-even more problematic when you factor in the higher price.

Nylon 12-plait Rope

Nylon stores in less space, is relatively tangle free, and absorbs a ton of energy in stretch. Interestingly, rock climbers use 3-strand, double braid, and kernmantle (braid over twisted yarn core), but never plaited rope. Neither do arborists or work-at-height professionals. Why? Because the loose weave can catch on rocks and sharp spots, causing function problems and damaging the rope. The weave gets pulled out of shape and we’ve broken a few strands when it snagged on a submerged tree. Chafe resistance was better than double braid, but not as good as 3-strand. On the other hand, it flakes better than anything else, and so long as your rope never comes across anything sharp, you’ll love this stuff. We prefer plaited ropes made from braided sub-ropes, such as New England Ropes MegaBraid II, over ropes made from twisted sub-ropes, such as Yale Brait.

Bottom line: Recommended, if the bottom is never rocky or foul.

Climbing Ropes

Lighter ropes (9-10 mm) intended for fast ascents and sport climbing, have thinner covers so that more rope can be saved for the energy absorbing core. You don’t want these. Fatter gym and expedition ropes (10-11 mm) put extra material in the core and have durability similar to conventional double braids. Tech editor Drew Frye uses retired 11 mm ropes and has been pleased with the wear. Climbing ropes offer superior knot holding and untying ability, a comfortable hand, and snag and tangle-free performance. They are more expensive (about 85 cents a foot), cannot be spliced, and are incompatible with windlasses.

Bottom line: An excellent choice if a lightly used retired rope is a available, but we wouldn’t run out and buy one.

Polyester

Forget it except for bridles. There isn’t enough stretch and it performed horribly in prior PS rode testing.

Arborist Ropes

The working load limit is equal to polyester, but without the concerns regarding fatigue and overheating. The product reminds us of the polyester/rubber increasingly popular composite mooring down lines (see PS May 2018, Elastic Mooring Systems). In both constructions, the chafe resistance of polyester is combined through smart weaving and the use of a more elastic core material. Like other double braids, these are not compatible with windlasses. They do not flake well, and are best coiled or stored on a reel.

Atlas Rigging Line

We experimented with a heavily used scrap rope made by Sterling. Although it had already seen heavy use by a tree service company, we were very impressed. Cover wear was less than marine polyester double braid, which was many times better than any nylon rope, particularly when wet. Stretch is about 4 percent at 10 percent breaking strength. Sterling costs about 96 cents per foot for -inch line.

Bottom line: Not rated, but it meets the stretch and durability requirements.

Samson Ropes Nystrom

This climbing rope stretches about 2.4 percent at 10 percent of its BS. It performs similar to Atlas but stretches less and the cover has a tighter weave. We found -inch diameter rope at a price of 83 cents per foot.

Bottom Line: Too little stretch for anchoring.

Bull Rope

Somewhere in between Nystrom and Atlas, this rope from Knot & Rope Supply has half the stretch of 3-strand nylon, but more than triple the stretch of polyester doublebraid.

Bottom line: Not rated, but another strong candidate.

Conclusions

We like conservatively sized ropes. They are easier to handle, longer wearing, and we think some the recommendations out there are frankly, deficient (see adjacent tables). Choosing a favorite rope was very difficult, because much depended on locker geometry, personal preference for hand, and whether splices or knots were desired. Pricing is generally close for equal quality. We like 3-strand best for durability, but plaited rope may serve better in a small anchor well. Early adopters may like arborist ropes, but we haven’t tested it enough to recommend it.

We used the same protocol that we used in previous abrasion tests. A modified wood lathe sawed line samples back and forth (a 3/4inch stroke) at seven cycles per second across the edge of a cinder block until failure.

To compare elasticity we used the manufacturer-supplied data and results from our past tests , when available (see PS March 2016, What is the Ideal Snubber Size,). Weve found most of the leading U.S. manufacturersYale, Samson, New England Ropes (Teufelburger), etc. abide by industry standards and publish reliable performance data.

- The polyester cover on this double braid rope was cut through and the core showed signs of damage.

- Amsteel is very resistant to abrasion when pulled lengthwise across an abrasive surface, but not when sawed perpendicular across the ropes braids.

- Our pendulum test rig sawed the samples laterally, perpendicular to the weave.