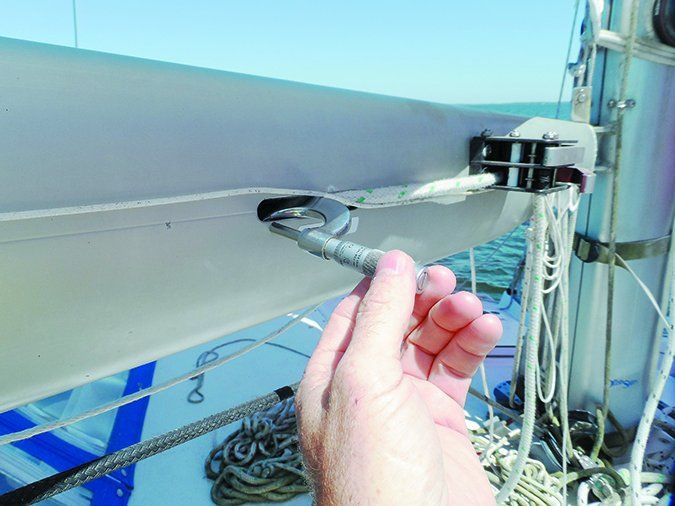

Every sailor eventually feels the pull to add hardware to their spars. Maybe a piece of hardware has broken off, or the fasteners look suspect. Or you perhaps you want to add mast steps, or a cheek block for external reefing.

We’ve covered deck hardware upgrades in various reports (search mounting deck hardware and backing plate in our online archives), adding mast hardware requires different skills. Most commonly, aluminum or mast attachments use a machine screw or blind rivet. Most are made of aluminum, and most attachments are by machine screw or blind rivet. Which is better, and what type?

It is easy to dismiss the blind rivet as a production shortcut, insisting that a proper threaded machine screw is stronger. But hundreds of thousands of beach cats have been built with riveted spar fittings, many left on beaches for decades, and the service history has been impressive. A blind rivet grips thin material tenaciously, pulling out only after the metal has distorted so far that a threaded fastener would have stripped and been long gone. The downside to rivets is their limited size range (only 3/16-inch is commonly used) and that they must be drilled out to remove hardware.

Machine screws let you remove hardware, but they also have weaknesses. Threading requires a certain amount of skill and practice. If removed repeatedly, aluminum threads will wear and strip. Over time, the threads may corrode, making removal impossible, or ultimately weakening the joint. Liberally coating the fastener and mating surface with an anti-seize coating will help prevent this (see Anti-Seize Coatings for Spars, PS July 2018), but not forever. Finally, if the spar wall is thin, only few threads can engage.

Sheet metal screws are seldom the best answer. These are designed for thin materials, generally less than .020 inch. Even if the hole is properly sized for thicker materials, sheet metal screws are prone to snapping during installation. The sharp points of sheet metal screws can cut, snag, or sever any ropes or wires inside the spar. The close cousins of sheet-metal screws-self-tapping and self-drilling screws-were not included in the test.

Drew Frye

What We Tested

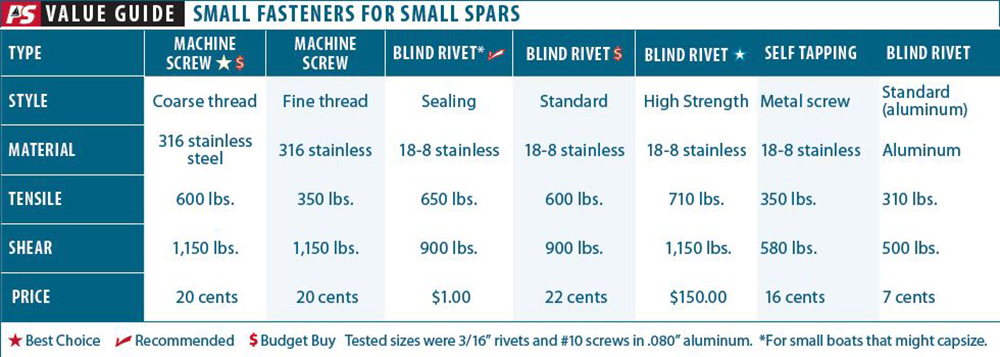

We tested three types of blind rivets: standard (for ordinary loads), sealing (with sealed stems to prevent any water penetration), and high strength (for higher load, with thicker material at the head and stem). Blind rivets are hollow-stem rivets designed for installation when only one side is accessible. We also tested machine screws (both coarse and fine threads), and sheet metal screws. We focused on 3/16-inch fasteners (#10), since this is the most common size for mast fittings on thin spars. Smaller sizes are reserved for very lightweight fittings, where strength is not an issue. Larger fasteners are generally through bolted or have backing plates.

How We Tested

Samples were assembled and tested for both shear and tensile (pull-out) strength. We tested using a broken spar from a Prindle 16 beach catamaran (0.081-inch thick aluminum). The cruising sailboat spars we measured for comparison ranged from 0.080 to 0.125 inches thick for boats approximately 27 feet long, and from 0.125 to 0.165 inches thick for a 34 foot boat. Rivets were common on the thinner spars, becoming less common as metal thickness increased, but were still used for small fittings.

Drew Frye

Observations

Backing plates are always a good idea where tension loads are high. However, in shear strength tests, all failures were by shearing of the fastener. Thus, straps, hounds, and strap-type vang fittings do not require backing, whereas cam cleats and pulleys that put the fastener under tension (outward force) will benefit from a backing plate or washer for a rivet and a backing plate and nut for a machine screw.

Washers in combination with blind rivets may be impossible when the back of the rivet is inaccessible (as is often the case), but it is sometimes possible to wiggle a backing plate into position.

Drew Frye

Machine Screw vs. Rivet

In our testing, machine screws and rivets were neck and neck in terms of strength. Rivets excelled in thin materials, and were simpler to install.

Screws were less forgiving for the novice. To test this, we intentionally used an over-sized tap to drill for the screws, or started the tap crooked, and in both cases, the strength was reduced by half. Thus, rivets are the winner in spars less than 0.08-inches thick and will likely be as effective as machine screws in materials up to 1/8-inch thick.

Metal fatigue. A loose fastener can gradually weaken the spar wall as it moves around in the hole under load. Our testers found that the large mushroom head of the rivet is less susceptible to gradual loosening by vibration and impact.

Drew Frye

Corrosion. Left untreated both screws and rivets are susceptible to corrosion. Our tests showed little difference between the two. The risk can be reduced by using a metal-free anti-seize such as Tef-Gel or Loctite (see Anti-Seize Coatings for Spars, PS July 2018).

Aluminum vs. stainless rivets. Aluminum rivets proved to be the weakest fasteners in our test, even weaker than fine thread machine screws. It is sometimes suggested that aluminum rivets eliminate galvanic corrosion. In fact, we observe the opposite to be true. The mast and rivet are different aluminum alloys, and it appears that the aluminum rivets are more active than stainless or monel in a marine environment.

Sealed vs. Open Rivets

Drew Frye

Filled with the hubris of youth, one of our testers once sailed a first beach cat out into the remnants of a hurricane, capsized in the surf, and snapped the mast. When he transferred the old fittings to the new tube, he dutifully sealed all of the joints, but he used open rivets, not realizing that the hollow stems can allow an appreciable amount of water to enter.

Some months later, he capsized again, and during that time the mast began to fill with water. Although the boat did not turn turtle, righting the boat was an epic struggle, and water shot out of the halyard exit at the bottom for some time, demonstrating that top four feet of the mast had flooded.

Bottom line: use sealing rivets on dinghy masts and anywhere water leakage must be prevented.

Fine vs. Coarse Threads

Just to complicate matters, machine screws come in both coarse and fine threads. Makers wouldn’t offer both if they didn’t each have unique benefits. So, which is better?

A fine thread bolt is about 14 percent stronger because the cross section area is slightly greater. The finer thread permits closer adjustment where gasket compression is critical. On the other hand, coarse threads resist stripping better, a critical advantage in thin materials. The larger threads are more fatigue resistant, and cross-threading is less likely, both important in soft materials like aluminum. Finally, coarse threads better allow for galvanized coatings and anti-seize compounds.

Bottom line: Coarse threads are the first for choice for aluminum spars and most nearly all stainless bolt applications. Fine threads remain the territory of high strength bolts on cylinder heads and the like.

Conclusions

We like threaded fasteners wherever the spar material is 1/8-inch or greater. They are removable, draw-up range is good and strength is predictable. However, when the material gets thin and soft, threads become weak.

Thus, a rivet is often preferred when the metal is less than 1/8-inch thick. This includes masts and booms on most boats up to 30 feet. Rivets are very well-proven in these applications.

The most important consideration is hardware design. If possible, the load should be entirely in shear and the load should be shared by enough fasteners to insure the working load is not exceeded. When an outward pull is unavoidable, it must be considered that the whole load may be carried by a lone fastener.

I’m guessing that $150 for a high strength stainless steel blind-rivet is some kind of typo?