Photos by Dan Dickison

While we all benefit from some amount of trickle-down technology from the Americas Cup races, some of the most relevant developments for cruisers come from the realm of singlehanded distance racing.

In the recent Velux 5 Oceans Race, four solo sailors piloted their 60-foot steeds some 30,000 miles around the globe in five separate stages, putting a number of innovative products to the test. Unique to this fleet is the Eco 60 concept, which is intended to diminish both expenses and environmental impact. The race required each boat to be equipped with at least three means of power generation, and two of those had to utilize alternative forms of energy.

Generating electrical power is particularly crucial on board a singlehanded boat. In this race, the competitors can be at sea for up to 30 days at a time, and each relies on power-dependent equipment, including autopilots, nav instruments, communication devices, and radar units. In addition, each of the Open 60s in this fleet has a can’ting keel, which demands significant power to operate.

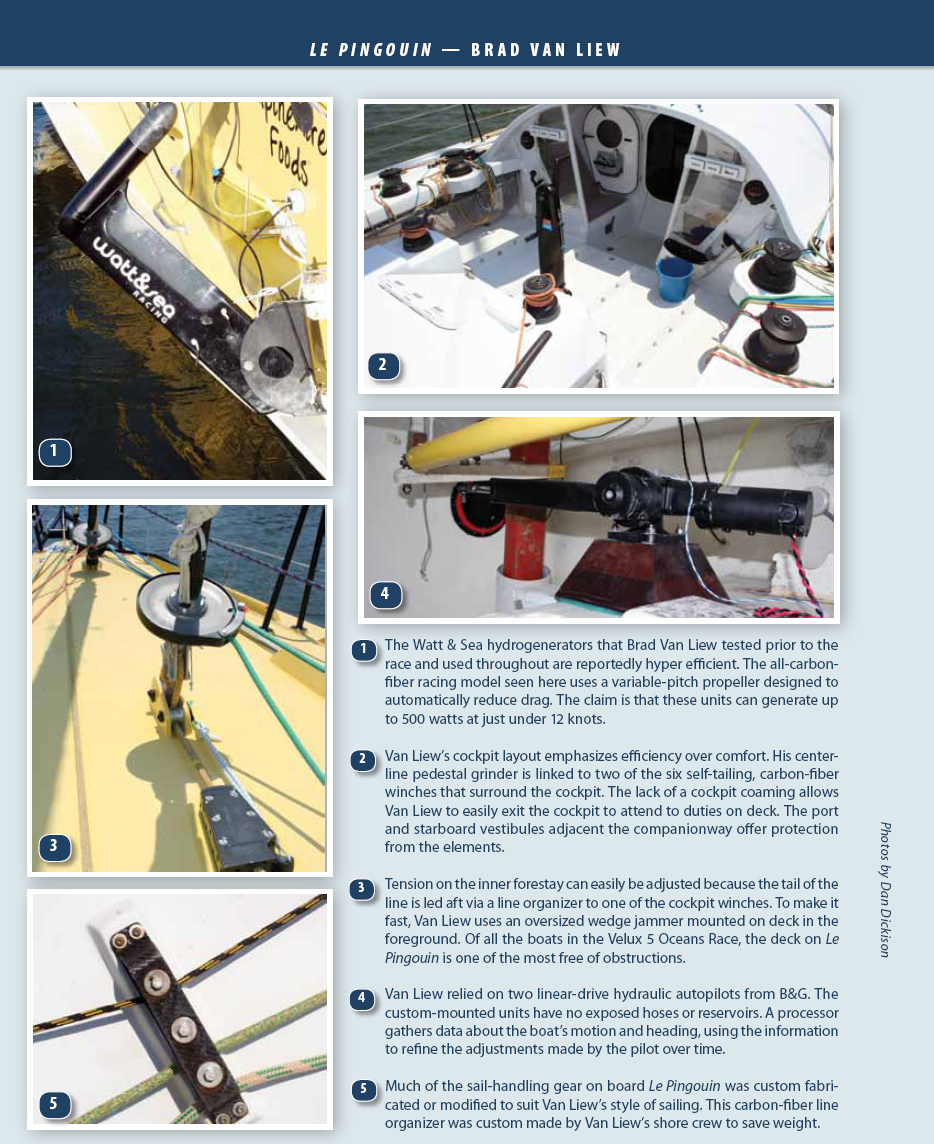

Among the four Velux 5 Oceans competitors who completed the race, two approaches to power generation and consumption prevailed. For two sailors, frugal consumption was the order of the day, and for the other two, maximum power generation was the key. Both Brad Van Liew, aboard Le Pingouin, and Zbigniew Gutkowski, on Operon Racing, fall into the latter category. Along with their auxiliary engines, solar panels, and wind generators, each had two Watt & Sea hydrogenerators on board. Because of the reported efficiency of these transom-hung devices, both Van Liew and Gutkowski enjoyed the rare phenomenon of surplus power.

Power Gluttons

Van Liew said his energy surplus gave him a significant edge over fellow racers. Ive got an advantage when it comes to generating power because of the hydrogenerators that Im testing, he said. With just one of them deployed, that gives the boat more power than I need, if Im sailing at over 8 knots.

Look at the data, he explained. I averaged 12 knots on Leg 1 and 13 knots on Leg 2. I havent really had to use the power from my solar panels. Because of these devices, Im running my radar almost all the time. In the last two round-the-world races, I never did that. Im the only guy in the fleet who can do it.

Gutek, as Gutkowski is referred to by everyone in this game, claimed to have carried only a minimal amount of diesel on board for each leg, approximately 10 gallons. I can do that because of the hydrogenerator, he explained during the races stopover in Charleston, S.C., earlier this year. It really keeps the batteries charged. My model is different from Brads because I have the cruising version. The propeller blades are fixed. The ones he has feather automatically, so Ive got more drag. Also, mine is all aluminum as opposed to the carbon housing that Brad has. But its much less expensive, and when my boat goes over 10 knots, that thing runs all of the electrical equipment on board.

Watt & Seas hydrogenerators were developed by Frenchman Yannick Besthaven, himself a solo sailor. Besthaven appears to have resolved the problems experienced previously with towed hydrogenerators. But there were teething problems with his prototypes as well. On his delivery from Charleston to the start in La Rochelle, France, Van Liew cooked one of his gel-cell batteries because, he said, the voltage [the hydrogenerators] were set to charge to was too high, and I didnt have the experience to know when to take them up out of the water. Ive learned a lot since then.

A further complexity regarding these hydrogenerators is the issue of deep-cycle charging. Veteran singlehander Bruce Schwab, whos the U.S. distributor for the new hydrogenerators, explained that the converter-regulator is one-stage, voltage-regulated charging, which is fine since the units are typically used for bulk charging and then raised out of the water afterwards.

Van Liew concurs: We worked with Yannick to refine our charging protocol. I actually hired a charging expert in Cape Town [South Africa], and we decided to switch from gel-cell to lead-acid batteries. It probably took me about 10,000 miles to figure out how to use the hydros to their greatest advantage.

Power Misers

No sailor should dismiss the other, more traditional school of thought regarding power: frugality. That outlook-embraced and epitomized by Canadian Velux 5 Oceans racer Derek Hatfield and British competitor Chris Stanmore-Major-compelled both of these singlehanders to devise individual strategies for coping with the lack of capacity for generating power on board their boats. Both initially considered using hydrogenerators, but each said he lacked the budget for that, and instead favored other solutions.

According to Hatfield, having a reliable wind generator was key for him. If Im very conscientious of power consumption, the 14 amps that I get from the Superwind 350 will provide all that I need for running the boat. My philosophy is that Im very frugal. Daytime or night time, I rarely run the radar. Usually, I come up on deck every 20 minutes, if its clear, and just take a look. Radar is a huge consumer of power. To me, its a big luxury to run it. If the conditions are really bad, such as fog or limited visibility, or there are lots of ships around, then I might run the radar.

Hatfield employed a similar approach to lighting on board Active House. This boat is outfitted with all LED light fixtures: running lights, cabin lights, everything. I use those very little. Theyre turned off most of the time. I have a masthead light that I run, and that illuminates the windex, which is all I need unless Im in the shipping channels or near land.

He said that his normal practice was to use his boats engine once every five or six days to bring his boats batteries up to full charge. Yet, he didnt need to use it at all for that purpose during both of the legs through the Southern Ocean, he said. And during Leg 1 (La Rochelle to Cape Town), I used the engine for less than 20 percent of my power. The wind generator is really the main source of power. It produces 12 to 14 amps. On average, I only [require a charging rate of] 7 amps, so the wind generator provides everything I need. Solar panels produce another 3 or 4 amps on top of that. So, providing there is wind and sun, I don’t need to run the engine at all.

Hatfield referred to his Superwind 350, as a new generation of wind generator. The amp output is really good, and its quiet. You can’t hear it at all. Whats unique is that it has feathering blades, so that at high speeds, it can depower itself.

The Superwind 350 comes with a safety switch; an advanced, adjustable, two-battery bank charge controller; dump load resister bank; in-line safety fuse; and a wind turbine thats rated and approved for extreme weather conditions in both 12-volt and 24-volt for $2,299. It was rated as the Best Choice in our July 2007 test of wind gens.

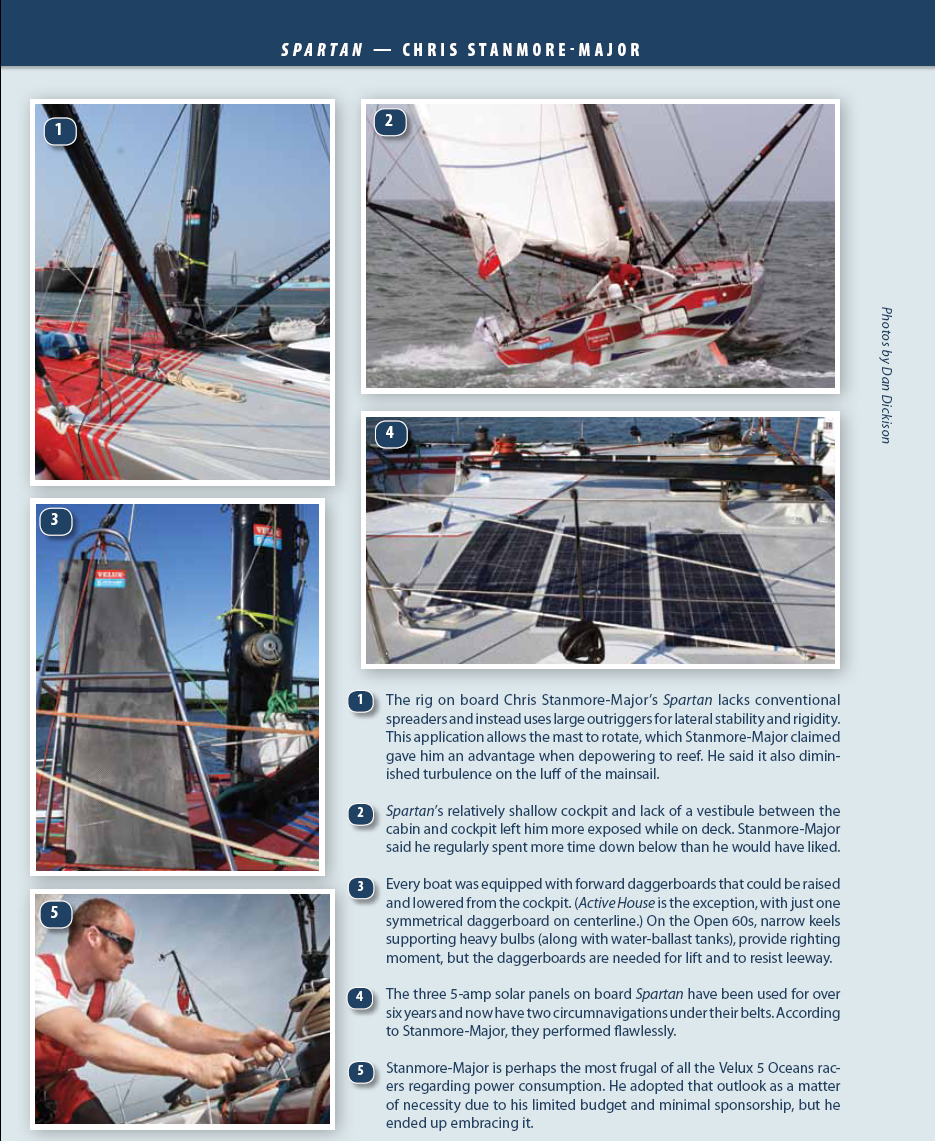

On board his aptly named Spartan, Stanmore-Major shared Hatfields outlook, if not his reliance on a wind generator. We didnt have the money to replace the solar panels, so these are the same ones that went around the world five years ago with Robin Knox Johnston in the last race. Theyre six 55-watt panels, and the maximum output in really sunny conditions is about 5 amps each. Thats quite a small output, not much more than a normal trickle charger, but its enough when youre doing everything possible to use very little power.

For Stanmore-Major, that meant rarely using the fix-mounted lights on board. Even though those are all LEDs, he instead used strap-on headlamps at night, and the batteries in those he charged whenever he ran his engine. He said he used the nav computer to do his navigation and then turned it off. Whenever he was in the cockpit, he would disconnect the instrument displays down below, and when he moved on deck, vice versa. Of course, the chartplotter (Raymarine E-120 touchscreen) has to remain on, but I always turn the background light all the way down so the unit operates more economically.

Stanmore-Major estimated that he needed only to carry 10 gallons of diesel on each leg of the race. He said he didnt rely much on his boats wind generator (like Guteks, it was also a D-400) because he said he couldnt afford the superstructure required to permanently mount it, so he used a temporary mounting pole when he operated it.

Photo courtesy of Ainhoa Sanchez/w-w-i.com

Conclusion

All four entrants in the most recent Velux 5 Oceans race were enthusiastic about the example they might be setting for other sailors regarding the potential for using alternative sources of energy. Among them, Van Liew was the chief cheerleader for new technologies that enable the use of renewable energy sources. Still, he said, he concurs with his fellow competitors regarding the charging issues they each experienced.

The hardest thing about using sustainable energy sources is the trickle charging. Sooner or later, youve got to get the batteries up to full charge, and trickle charging wont do that. I think the problem seems to be that were using car and truck battery technology, and some of these systems-like those in the a hydros and in Dereks wind generator-are using aerospace technology.

Van Liew also pointed out that many contemporary Open 60s were using high-capacity lithium-ion batteries, which are capable of handling the higher charging rates. (PS reported on lithium-ion batteries in May 2011.)

Despite those challenges, Van Liew regards these new devices as ideal for the short-distance cruiser. The problem is, trickle charging doesn’t work for the long haul, but if youre in a cruising environment where youre not at sea for more than seven days, and then you get to a dock and plug in, there shouldnt be an issue.

I made it all the way across the Atlantic without using a drop of fuel after the alternator on our engine failed. We simply relied on the hydros. After the experience I had in this race, I don’t think I would ever own a boat without some means of alternative power generation.