We originally reviewed the Tanzer 22 in the December 1, 1981 issue, but a friend of ours did such a good job restoring the 25-year-old T-22 he inherited from his father that we decided to take a second look. The T-22’s accommodations haven’t gotten any more workable than they were when we first sailed her; her aesthetics are, at best, “unique,” and we doubt she’d have much luck in a drag race with lighter 22’s like those that have come on the market since she was introduced in 1970. Still, she’s simple and fun to sail. She’s also capable enough as a cruiser and challenging enough as a racer to make her one of the most popular boats of her type ever built. There were 2,270 sold.

The Tanzer 22’s shortcomings may illustrate some of the ways that sailboats have gotten better over the years, but her strengths are still genuine. A pint-sized weekender/racer that wears well, the T-22 has earned remarkable loyalty from her owners.

Johann “Hans” Tanzer, designer/builder of the T-22, grew up in Austria where he apprenticed as a boatbuilder. Then he went to Switzerland where he built and raced dinghies and small boats. Finally he emigrated to Canada. He worked at first on one-offs, dinghies, and raceboats before starting his own shop. Tanzercraft built Lightnings, International 14s, and Y-Flyers. “Right from when I started in Austria the main thing was always racing…to make a boat go fast,” Tanzer said from his home near Dorion, Quebec. “Then I thought, ‘What about a boat for the family, for the average guy?’”

His answer was a 16-foot daysailer he called the Constellation, his first design. When his company expanded and became Tanzer Industries, Inc. in 1968, the Constellation became the Tanzer 16, and then Hans Tanzer drew up an overnighter version, the next step in appealing to the average guy.

Next up was the Tanzer 22.

“I was inspired a bit by Uffa Fox, some by George Hinterhoeller and what was happening at C&C; I knew how to make boats go fast. But for the 22 I wanted a boat that was first of all safe, that would be forgiving, that you would not need to be expert to sail, that would let families sail together.”

Design

The T-22’s cockpit is large. It is well over 7′ long and (in the absence of side decks) utilizes the whole of the boat’s beam. It provides room to seat six and lets four sail comfortably. The well is deep, the seat backs are high, the seats slope outboard; it is secure and comfortable.

“We’ve sailed the boat for more than 20 years,” said an owner from Maine. “We like the roomy cockpit and solid feel. It’s a great boat for children as the cockpit is so deep and spacious.” Most owners say the same; its over-sized cockpit is a key to the appeal of the boat.

It is also, however, too big to drain quickly. And there is no bridgedeck. We asked Tanzer about the potential danger of filling the cockpit offshore and/or in heavy weather.

“The corner of the house deflects water and protects the cockpit from taking solid waves,” he answered. “My son and I took out the first boat we built and tried to break it. We had the spreaders in the water and the waves still didn’t come aboard. The water just streamed aft along the deck. The hull has plenty of freeboard and the cockpit sides are high. I think I should have made the cockpit more self-bailing, though.”

John Charters, once service manager at Tanzer Industries and now editor of the class newsletter, said, “Many owners have, like I did, added drains in the forward corner outboard end of the cockpit benches to drain what water comes aboard to the scuppers. I’ve seen T-22s with their keels out of the water, but I’ve never seen them swamp or heard of one that sank. When it starts to blow hard, though, I always sail with the bottom drop board in place in the companionway to make sure no water gets below.”

The T-22 displaces 2,900 pounds (3,100 for the keel/centerboard version). That’s heavy, even by 1970’s standards. The Catalina 22, a contemporary of the T-22, weighs 2,150 pounds. The more modern J/22 is just 1,790 pounds (and she’s hardly the lightest racer/cruiser available in this size range.) It’s natural to think of displacement as “dead weight,” especially in a small boat where size puts an effective limit on sail area. However, it can also translate (as we feel it does with the T-22) into robust scan’tlings and healthy ballast/displacement ratios. “Everything on the Tanzer is built extremely heavy-duty,” said one owner.

Tanzer put much of the T-22’s buoyancy in the after sections. As a result, she accommodates the weight of a cockpit full of sailors without squatting or deforming her sailing lines. Finally, the T-22 provides little of the “corky” feel that some small boats do. It would undoubtedly be possible to build the boat lighter today. That might improve it some, but the T-22’s solid feel and generous payload have endeared her to “the average guy,” and much of that is due to her heavy displacement.

The mainsail is small (112 sq. ft.) with almost no roach. Her spar is a “tree” in section and virtually unbendable. A 200 sq. ft. (170%) genoa provides the real muscle of the sail plan. We prefer a big controllable mainsail married to a small, non-overlapping jib for versatile, efficient sailpower. In a bigger boat an out-sized genny can become a man-killer. However, the Tanzer’s sails are small enough to handle. Putting most of the horsepower in the foretriangle is one way to limit weather helm and boost square footage for light air performance. A 375 sq. ft. spinnaker is allowed by the class. The T-22 sailplan, though dated, is proven and straightforward.

The hull and foil shapes also are products of their time. Not nearly so sharp of entry nor flat of exit as a modern racer/cruiser, hers is a “through-the-water” hull.

Like many racers from the early 70s, especially those produced by neighboring C&C, the T-22 has a swept-back keel. Designers have since plumbed the underwater mysteries with deltas, trapezoids, ellipses, bulbs, and wings. You don’t see swept-back fins much anymore, but they provide a generous and wide “groove” (which suits the boat well for the average sailor) and minimize wave-making resistance (which helps the boat accelerate and adds to her lively feel). Other shapes have come into fashion, but the T-22’s fin works well.

The same is not entirely true of the T-22 rudder. Tanzer’s original design was a shallow, aft-raking, semi-scimitar. He wanted, he said, a lift/drag profile to match the keel’s and a “fail-safe” element to keep sailors from “driving the boat into trouble.” What he got was a foil that tended to lift clear of the water and ventilate when the boat heeled in a puff.

“We should have replaced it right away,” said Charters, “but it took a long time before we developed a new one. It was deeper, semi-balanced, and straight on the leading edge. It worked! What used to involve fighting ‘on-the-edge’ weather helm is now a two-finger operation. We let the new rudder (it was developed by one of our owners and costs only about $200) and old rudder race together in our regattas.”

There aren’t many boats that look like the T-22. Her straight housetop/deck extends from stem to cockpit. The bow is spoon-curved but a bit bulbous. Very modern-looking in profile, the sheer is traditionally sprung, traced by a cove-stripe/rubbing strake that runs along the deckless “deckline,” which creates the illusion of low to medium freeboard while the actual hull/house sides are quite high. Except for the visual trickery involved with this cove stripe, Tanzer didn’t invest much in trying to make his boat look like something it wasn’t. Her big cockpit, raised side decks, and “good-for-the-average-guy” hull were the main thing, and that is what you get. From some angles she looks saucy, from some others silly.

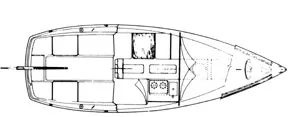

Accommodations

Dinettes were very popular in the ‘70s. “Convertible space” was the magic key to making little boats accommodate big people. Obviously, you have to bend some to cruise a boat this small.

The T-22’s headroom (4′ maximum) makes that point emphatic. So do the sharply tapered V-berth and the narrow quarter berth. The physical and visual “elbow room” created by taking the house side out to the rail, however, helps make the cabin less cramped. Still, the need to convert is a haunting reality. Change the table into the double berth, lift the forward berth to access the head beneath, convert the front-opening ice box into something you can live with underway, the hatch cover into a pop top, etc. and, after a while, “two-way space” becomes a mixed blessing.

Ventilation is another sore spot, but stowage (except for the “silly waste of space given over to the sink and ice box” noted by an owner from Lake George, New York) rates as “good” to “very good” with most owners. Hardly the heart of the design, the T-22’s interior has still let thousands enjoy the sort of limited cruising she was meant for.

Construction

Eric Spencer, Tanzer Industries president from 1968 until 1985, now runs Yachting Services, Ltd. (Box 1045, Pointe Claire, Quebec H9S 4H9, Canada; 514/697-6952) that, among other activities, sells parts for the more than 8,000 Tanzers out there.

“Hans was always on the shop floor,” Eric said, “rarely in the office. He was prone to over-engineering things. You can see it in the T-22 keelbolts. They’re the same size we later used on the T-31. And we used the same mast section in the 26 with no problems. And the rigging—everyone else was using 1/8″ wire; Hans had to have 5/32″”

The hull/deck joint is an outboard flange joined by semi-rigid adhesive and 3/16″ machine screws on 6″ centers. Charters, the ex-service manager, said, “Though many owners report no leaks, the joint can leak—sometimes. One of the simpler systems and certainly one of the easiest to fix, it has some minor faults. Impact to the hull, even squeezing between lifting slings, can break the adhesive bond. Both the machine screws and the Monel pop rivets used on some boats may loosen where fasteners pulverize the fiberglass. Remember that the T-22 sails with her rubrail in the water. That pressure can turn even a tiny gap into a leak.”

Charters recommends removing the rubrail, (“but leave it attached at stem and stern or you’ll never get it back on,”) replacing (with oversized machine screws or through bolts) loose fasteners, and redoing the seal using BoatLIFE Life-Caulk or 3M 5200. This “two- to three-hour process,” he said, will renew most boats’ hull/deck joint to tightness.

The portlights originally relied on a sponge rubber inner gasket and a hard rubber outer seal. These, too, most likely will need to be renewed on older boats. Replacing the inner seal with butyl tape is one suggestion. Cutting new, over-sized ports from an acrylic or polycarbonate material (the original plastic clouds with age) and fastening them to the house side with sealant and mechanical fasteners is another good fix, owners report. “The sponge and spline seals I purchased (about $100) for the hull ports from Eric Spencer made re-doing the cabin ports easy. It took four hours and the leaks are completely gone!” said the owner of a 1981 model in Ontario.

An interior hull liner incorporates the berths, cabinets, sole, etc. It’s easy to assemble, and strong if done meticulously (as it seems to have been on the Tanzer floor). But when this construction system includes molded headliners it is hard to move or add deck hardware.

Resin-rich fiberglass from the era when the boat was first built is prone to becoming granular and powdery around screw holes. The early gelcoats craze easily. Still, most owners seem happy.

“Finish has held up very well over the years,” and “Boat looks like new,” were comments frequently heard about the T-22.

Our friend’s 25-year-old heirloom, however, had passed that stage. To bring the hull back he washed it down with Interlux 202, patched dings and scratches with epoxy and microballoons, then brushed on two coats of marine gloss enamel. The result rivals a professionally sprayed job while the cost (time, labor, and materials) is in keeping with the value of a quarter-century-old 22-footer.

The T-22’s iron keel is a sore point. Iron is 40% less dense than lead so you need more of it (at a cost in added wetted surface) to give the boat sufficient ballast. And it rusts. One owner said he discovered no primer beneath the bottom paint applied at the factory. Many sailors know the agonies of fairing a keel that scales and peels. For race-ready perfection you can fill the major craters with epoxy and then build and sand with a system like Interlux’s Interprotect (2000 E coating and V135 Watertite fairing). Not many owners are that far into their fleet racing, but most wish that the keel originally had been made of lead.

Performance

Hans Tanzer’s solid background in performance boats, dinghies, and daysailers helped him design the sort of “safe and forgiving” yet lively sailboat he was looking for to appeal to the average guy. He struck a number of balances well. The big cockpit (little cabin), good stability (stiff but not rock-like), controllable rig, and powerful yet easily driven hull combine to give her good manners.

We sailed our friend’s newly painted boat through a drifty morning and a sea-breeze afternoon. In the river she was quick, but tacking the genoa made us wish for a smaller jib and bigger mainsail. On the ocean she was solid and dry. She tacked in 75° in smooth water, and short-tacked up a channel, quickly getting her foils working after a tack.

With a 15-knot breeze she surged rather than surfed. Her deep, rounded afterquarters make her easy to steer but reluctant to get up on plane where a J/22 might.

The strongest T-22 fleets are in Montreal and Ottowa, but American fleets are active, too. Said Charters, “We were the first cruiser/racer invited to CORK (Canadian Olympic-training Regatta at Kingston). We’ve moved now to the offshore course and start 5 minutes behind the J/24s. Usually, the first T-22s, light air or heavy, catch the straggling 24s. We’ve never beaten the winners though.”

PHRF ratings for the T-22 range between 92 and 98, while the J/24 rates between 88 and 98.

The standard mainsheet is attached to a strongpoint on the cockpit sole. A number of traveler options have been tried. Tracks mounted on the sole rather than on a cross-cockpit bridge cut up the cockpit less but offer less control.

You might point higher if you could sheet the genoa tighter, but the shrouds don’t let you. Also, those shrouds, not in perfect alignment with the tabernacle hinge at the base of the mast, must be loosened before you lower the mast. Depending on how (and how much) the wind is blowing, that can be a problem.

The keel/centerboard version (about 10% of the boats sold have this configuration) is less close-winded and, according to racers, not that much faster off the wind than the full keel. Either needs at least 5′ of depth to float off a trailer, so being ramp-launchable involves sending the trailer into the water on a tether.

Conclusions

One of the biggest pluses for the boat is the 700-member owner’s association. It maintains Tanzer Talk (a newsletter) and egroups.com/tanzer (a website) that make fellowship as big a part of ownership as you’d like it to be. The owner of a 1979 model from Long Island Sound reports “an outstanding T-22 website (http//www.tanzer22.com) and network of owners who are always willing to help with ideas and experience.”

Built efficiently but using high quality materials throughout the boat (even the pop rivets are Monel), the T-22 commanded a higher price than many of her competitors.

A prospective buyer can still find cheaper ways into the pocket cruising experience, but not many offer the combination of big boat feel and reliability, plus raceboat life, that have suited the T-22 so well to Tanzer’s “average guy.”

Thank You! Good article. Just purchased a Tanzer 22. Needing to get proficient at raising and lowering the mast.

I received a few Tanzer.22 Newsletters with the boat. In Volume 2 Numbers 21 to 42 page 82 has a good article about ” Mast raising or lowering”.

Its quite descriptive but a little confusion. It was written by Brian Rees from CA, I would love to talk with him and have him explain the details.

If you know the article, review it and feel free to comment.

hank you

Excellent article and review, thank you!