In the words of an old automobile commercial, the Soverel 33 “is not your father’s Oldsmobile.” If anything, it’s a stretch to include any variation of the word “cruise” when describing this boat, since it’s best known for its racing pedigree. Nonetheless, she doubles as a cruiser, as the owners of Pegasus, our Seattle test boat, will attest. Her accommodations don’t include television cabinetry or a microwave, and amen to that.

Company History

The Soverel 33 was produced between 1983 and 1988, chiefly by Soverel Marine in North Palm Beach, Florida, but also by three other builders (more on that later). There’s a debate about how many hulls were produced, but the best guess is 90.

Soverel Marine was owned by Bill Soverel, who had a 23-year career as a Navy pilot, but was also a successful sailboat racer with an accumulation of trophies that included MORC championships. He entered the boatbuilding arena in 1961 with the introduction of a 28-footer designed by Daniel McCarthy that enjoyed a modicum of success. Other models ranging in size up to 48 feet were produced before operations ceased in 1988.

In the early 1980s, son Mark, a world-class racer, designed the Soverel 33, a successor to a winning 26- footer. To that point, Mark had drafted winning designs for IOR, MORC, and Admiral’s Cup competitors.

His intent in producing the 33- footer was to develop a fast, light sloop that would excel in a one-design fleet on the race course while providing couples, or a family with young children, with “camper style” amenities.He succeeded.

Appearance

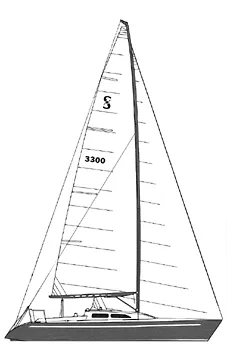

Two decades after her introduction, despite evolutionary changes in yacht design, she’s still a looker, with lean, low topsides and a moderate bow overhang coupled with a very subtle, nearly flat sheer leading aft to a reverse transom. A low cabin coupled with a 50-foot tall, 15/16 rig, creates a sleek profile. In the design style of her day she has a wide ‘midships beam at 11 feet, with moderate hull flare.

Rig and Deck

Her rig is a bendy, double-spreader section outfitted with straight spreaders supported by Navtec rod rigging. The backstay is split several feet above deck level and attached at the transom to pairs of blocks that allow the rig to be tensioned easily by the mainsail trimmer, who sits forward of the helmsman. Checkstay controls are led from the aft quarter to the mainsail trimmer’s station as well. Checkstays were reportedly installed rather than running backstays for two purposes: they prevent bending and pumping of the rig; and, they did not suffer a penalty under MORC handicapping rules of the day.

Halyards and sail controls, including vang and reefing lines, are led aft to the cockpit, centralizing sail management.

Seats in the cockpit are 8′ 4″ long, providing adequate space for trimmers to work fast without fear of injuring other crewmen with their elbows. Similarly, there’s room for four adults to lounge when dockside. Since the boom ends forward of the tiller, and is more than 5′ 10″ off the cockpit sole, the risk of head banging is reduced.

The traveler is located 38″ aft of the companionway, allowing the mainsail trimmer to perform his tasks without interfering with helmsman or trimmers. Despite the location of the track, it doesn’t seem to reduce comfort much at the dock.

Jib cars housed on sailtrack located at the base of the cabin run from the mast to the cockpit, affording excellent sail-shaping ability. When new from the factory, sheets were led to Lewmar 43 primary winches; those atop the cabintop were Lewmar 40s. In most configurations, spinnaker sheets are led to blocks aft of the primaries, then forward to the coachroof. That arrangement allows a grinder to exert maximum strength in a blow while the trimmer can stand at the shrouds. Side decks are wide enough to allow the foredeck crew to maneuver safely, and also provide a comfortable space to sit when not riding the rail.

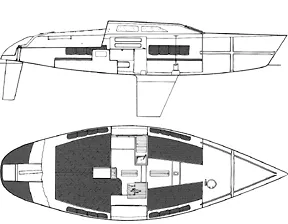

Belowdecks

The space down below is best described as a wide open area into which cabinetry for a sink to port, navigation station/food prep area to starboard, and two settees have been located. Quarter berths occupy the aft corners, and a minimalist head is located forward of the main bulkhead.

The boat was designed primarily for performance, not creature comforts. The area is 4′ 10″ wide at shoulder level, and 9′ 8″ wide at the settee backs. Nonetheless, the co-owners of Pegasus cruise the boat for two weeks every summer with their families—usually a couple and a teenager or two at any given time. The accommodations are minimal, but not Spartan. Dinner, however, is typically prepared on a hibachi or eaten shoreside.

The saloon has 5′ 10″ headroom at the tallest point. The stepped-through mast section is prominent in the saloon, as are the tie-rods for the shroud bases. The shroud bases are set well in from the rails to allow narrow sheeting angles, but this means that the tie-rods angle inboard across the settees and terminate on chainplates on the inboard settee sides. This no-compromise arrangement for supporting the rig is no comfort factor.

The mast is secured by bolts at its butt that allow adjustments that may improve sail shape and performance, depending upon winds and sea state.

The settees have a unique design that offsets the lack of built-in cabinetry. Since they are 33″ deep, they provide a comfortable sitting area. However, backboards may be mounted in wooden brackets that convert them to 24″ wide berths. A by-product of that arrangement is the creation of 10″ wide, 24″ tall storage bins behind the settees, in which crew gear may be stored. These spaces are excellent and easy to access. It’s too bad fancier boats rarely have them.

Space below the starboard berth is occupied by an 8-gallon fuel tank; the water tank is under the port settee.

The galley is defined by a shelf running fore and aft, onto which a 25- gallon cooler can be secured in place. The two-burner alcohol stove that was standard equipment is housed in a recess in the counter measuring 20″ x 12″ x 6″. The owners of Pegasus still use the original unit. A single sink is equipped with a cold-water pressure pump. Shelves located on both sides of the hull run from the companionway to forward bulkhead, providing 10″ deep storage behind sliding acrylic doors.

Opposite the galley is a 49″ long nav station countertop on which cook’s helpers or the navigator may work.

Outboard is shallow shelving on which charts and instruments may be loosely organized. Absent boxes into which instruments can be mounted on the cockpit bulkhead, they intrude into the cabin, and wires are exposed to potential disconnects by crewmembers.

The head, such as it is, consists of a toilet oriented athwartships with 32″ of headroom between the seat and the deck. Opposite is a cabinet in which a sink is mounted on a small counter. Since there’s no provision for a shower, a solar bag will be a handy addition to the gear list.Privacy is afforded by a curtain.

Forward is an 6′ 8″ long space designated for sail storage, with boards attached to the hull on which spare sheets and guys can be attached when not in use, or drying. Conceivably, cabinetry fitted to the contour of the hull could provide a more organized storage area or, in a pinch, a V-berth for a munchkin.

At the other end of the boat, bunks are huge—9′ 6″ long and 4′ 0″ wide. There are shallow stowage areas underneath.

The engine box is constructed of lightweight fiberglass that provides little sound deadening. It slides forward to provide reasonable access to fuel and oil filters and the back of the engine. However, the space behind the engine is wide open, providing storage amidships for large items.

Construction

With the exception of five flush-decked boats, there’s little difference between the first and last Soverel 33s produced, though they originated with four different builders. Of a total of approximately 90 boats constructed, beginning in 1983, the first 69 were produced at Bill Soverel’s plant in Florida. Hull numbers are not consecutive, however, so a gap between numbers 44 and 66 resulted in the last production hull being number 119. Of the remainder, the five with flush decks were produced at Republic Boats in California in 1984; 19 at George Olson’s Santa Cruz plant in 1985, and the last small batch at Tartan Yachts’ plant in North Carolina, according to Tim Jackett, Tartan’s chief designer.

Those constructed in Florida and on the West Coast were typically headed to the race course. Those constructed at Tartan’s plant have better-finished interiors and more amenities. In Jackett’s words, “Mark was very innovative in both the design and construction of the boat. He constructed boats with an eye towards avoiding the addition of unnecessary weight, and built them just strong enough so they wouldn’t break. We took a different approach with the boats we built.” The original boats weighed approximately 5,200 pounds; Tartan’s closer to 5,900. Most weigh approximately 5,800 pounds with mast, sails, and gear aboard.

Tartan discontinued production only because the company needed additional space in its factory for construction of its primary line. That was followed shortly by a downturn in the industry that also caused cessation of construction of the West Coast boats.

Hulls and decks produced in Florida were cored with 1/2″ Klegecell encapsulated in 3/4-oz. mat and 18-oz. biaxial roving. Decks were cored with 5/8″ Klegecell following a similar lamination schedule. The keel is ballasted with 2,800 pounds of lead, and secured to the hull with 5/8″ bolts reinforced by an aluminum backing plate.

Republic boats were cored with Divinycell; Olson’s with balsa; Tartan’s with Klegecell hulls and balsa decks. They were constructed of four modules— the hull, a liner that created the interior while stiffening the hull amidships and aft of the companionway, and two modules joined at the cockpit-cabin area to produce deck and cockpit.

Mark Soverel delivered some new boats with instructions for adding hull stiffeners to reduce oilcanning forward of the main bulkhead. Though oilcanning in a hull over a long period of time may reduce structural integrity, Soverel’s main concern was the effect that flexing of the hull has on performance. After hull #16 left the factory, its successors were constructed with two vertical stiffeners in the bow. In the meantime, he produced a technical bulletin outlining steps necessary to facilitate the alteration.

The design of the chainplates also deserves attention. On most boats, shrouds that have bases inboard of the rail are connected to tie-rods that are attached on the inner side of settees to a steel strap. Of Soverel’s more radical (but standard) arrangement in the 33, Tim Jackett says, “In that layout, the steep inward angle of the rod loaded the deck in the horizontal plane, as well as the vertical caused by the rigging loads. This is only unusual in the high horizontal inboard load that resulted at the deck. Decks cored in this area with balsa or foam did not have the sheer strength, and when heavily loaded the chainplate would creep inward.”

As a consequence, lamination in that area was increased on boats constructed at the Tartan factory. Jackett says that making the repair is a simple matter of “removing the chainplate, cutting out the coring, and relaminating with solid glass. Not too tough for a decent glass man.” We noted that Pegasus, which was built in Florida 17 years ago, shows little wear.

The Soverel 33 was originally powered by the 8-hp Yanmar 1GM (now 1GM10), but we note that several are being run now with transom-mounted outboards up to 9.9 hp.

Performance

You have two alternatives in your sailing style aboard this boat: Race fast or cruise fast. In the first instance, put a bunch of people on the rail to keep her flat. Depending on the region, she rates 83-98 under PHRF handicapping; Pegasus was rated 98 on Puget Sound. In cruising mode you can hoist smaller sails, let her heel a bit, and still leave “performance cruisers” on the horizon aft. Should the wind pipe up, be prepared to shorten sail.

During our test sail we sailed with a full main and 150-percent genoa, and a crew of eight. Winds were initially 6-8 knots as we sailed close-hauled at 5.7-5.9 knots, the skipper steering with one finger. (In lighter breezes she’s trimmed to induce a bit of weather helm.) When windspeed increased to 7-9 knots, we placed five bodies on the rail, sailed flat, and boat speed immediately increased by a half-knot.

As if to show off the light-air performance for which she is noted, when the wind dropped to 3 knots, we put her on a beam reach and saw her maintain speed at better than 4 knots, making her own wind in the manner of lightweight multihulls and iceboats. With a .75-ounce spinnaker hoisted in 4-6 knots of wind, boatspeed increased immediately and held at better than 6 knots. These readings were taken from the boat’s instruments, which might have been optimistic, but if so, not by much.

Owners say they begin reducing headsails in more than 13-15 knots of air, and reef the main in 18-20 knots.

Conclusion

The Soverel 33 should not be confused with mainstream “performance cruisers.” This is a racing boat, and her obvious strong point is her performance, especially in light air. However, that’s not to say that the boat can’t be cruised, given the right mentality on the part of the crew. The boat is well-equipped and can be handled by a couple. The cockpit is large enough to provide crew with a comfortable sitting area. She’ll sleep four comfortably. (On race weekends she’ll perform well with a crew of six.)

On the opposite side of the ledger, cruising will be “camp-style.” Meals will be a laptop affair, whether in the cockpit or below. A cook will be frustrated if attempting to produce anything more exotic than sandwiches or canned-fare-in-a-cookpot. The head lacks size and privacy.

The Soverel 33 was originally priced at $46,000. A survey of the class website and the BUC Used Boat Price Guide online (BUCNet) showed several boats on the market today for between $17,000 and $24,000, and one for $34,500.

Mark Soverel died in January of this year, far too young. But it’s good to know that he left a boat like this behind as part of his professional legacy—a boat for the young at heart.

The Soverel 33 Class Association website at www.soverel33.com is active, and a model community for owners’ groups involved with purpose-built boats from similar-sized production runs. It should be your first point of reference if you’re interested in joining the Soverel ranks.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Owner’s Comments.”

Hi Darrell,

We have owned a 1974/75 30 foot Soverel since 2005. Currently, we have it in the Riverside Marine boatyard in Ft. Pierce, Fl. and are doing extensive work on it. We live in Sebastian, Fl. and have had a lot of great adventures on our boat the “Adios” between the Bahamas & the Indian River, somewhere along the way we lost our centerboard and would love to replace it or make a new one based on the original specifications. Do you happen to know where we could find the original specifications for the centerboard; dimensions, weight and material used when the boat was manufactured?

Alternatively, are there any good sites online that you know of where we might be able to find a used Soverel centerboard for our make & model?

Thank you so much!

Tom & Lisa Wright

P.S.- She is starting to look terrific, decks and hull repainted and now Tom is working on rewiring and interior, he replaced the original diesel engine with a Yanmar in 2006.