Shortly before Ben Lexcens Australia II shook up the New York Yacht Club and the world by walking off with the Americas Cup, some other upstart Aussies were making themselves known Down Under.

Richard Ward and his mates were into multihulls. Like a fellow aficionado named Hobie, they thought everyone should have one. By 1982, Maricats-built in Wollongong (the Sydney suburb where Seawind is located today) and sailed off the beach-were going 3,000 strong around Sydney. Then came the Seawind 24. One of the success stories of the 1980s, this mini-cruiser sold more than 350 boats.

The Seawind 850 (1991) marked the maturity of Wards multihull company, but it was the 33-foot 1000 (1994) that made Seawind the biggest catamaran builder in Australia. That role has encompassed other designs (like the Seawind 1200) and projects (like the Formula 40 Simply the Best), and Seawind has not stopped growing. In 2000, Ward and crew acquired the Venturer line of luxury power catamarans, and more recently, the company teamed up with New Zealand engineering firm High Modulus to upgrade the Seawinds construction process.

Although the hull and deck of the boat we tested were made using conventional hand layup, the newer Seawinds-thanks to the recent partnership-are now made using a high-tech resin infusion process. Making use of closed molds, controlled-environment curing, and vacuum pressure, Seawinds new approach is in line with developments at production and custom shops around the world. By reducing resin content, increasing wet-out, and improving the bond between core and skin in a laminate, resin infusion is recognized as an upgrade in the quality of glass-fiber construction.

Well-regarded for Americas Cup efforts and projects like the experimental Playstation (Steve Fossetts extreme catamaran), High Modulus already has provided personnel (like composite engineer Richard Hallowes) to Seawind and is in the process of preparing core kits for the 1160 hull, deck, and liners.

Design

Forty centimeters is hardly more than a foot. You wouldnt think such a small change in length would herald a significantly different design, but Seawinds 1160, just slightly smaller than the 1200 that preceded it, is different indeed. Among the innovations that helped the 1160 win honors as the Australian Marine Industries Federation Boat of the Year for 2005 are a clever tri-fold door assembly, a self-tacking jib, a fold-away bowsprit, and stem-to-stern hull windows.

The 1200 was launched in the 1990s and aimed at charter companies working in the Whitsunday Islands. It offers four-cabin accommodations and two full-sized heads. The settee in the main saloon seats 10. Its builders say the 1200 is equipped to the standard of a luxury apartment. Seawind produces a half-dozen or so of these palaces per year, but thats hardly their whole story.

Launched in 1994, the Seawind 1000 has gone on to sell over 150 units. Key to the 1000s popularity, Ward says, is its open cockpit/saloon. We were seeking a boat that was a pleasure to sail for everyone aboard, he explains. The SW 1000s central cockpit flows straight out to the aft deck. Everyone on deck has the feeling of being together. With the aft deck accessible from the transom steps, this whole area becomes a focal point at anchor, too.

Introduced near the end of 2004, the 1160 is something of a marriage between the cruisability and solidity of the 1200 and the popular openness and zip of the 1000. The magic wand that makes bridgedeck space convertible on the new design is a set of three panel doors. When deployed, they enclose the saloon and offer the sort of lockable, secure, and cozy indoor area thats missing from the 1000. To open up the bridgedeck, fold the panels together and hoist the assembly up and out of the way. This yields the same indoor/outdoor space that has made the 1000 connect with owners.

Hinged on its forward end, the combination latches to the overhead arch (or targa). The doors are stout, and we worried about what would happen if they came adrift. However, a close look at the mechanism (doubly fail-safe with lanyard and latch) and periodic examinations underway convinced us the hazard was more hypothetical than genuine.

All of the Seawinds have mini-keels. Ward explains how this reflects his design philosophy: The boats offer great sailing and good performance, but they are not racing boats. The Seawind approach favors the practicality, simplicity, and grounding protection afforded by keels over the higher efficiency made possible by using daggerboards. The Seawinds keels are not shaped to afford upwind lift nor small enough to prevent downwind drag. They do allow the boat to dry out and protect its rudders and propellers from underwater hazards. The keels are thick glass, so any damage to them is easily repaired, Ward adds.

The same priorities are evident in hull shape. Length-to-beam ratio is more important as an arbiter of multihull speed than raw waterline length. The skinnier the hull or the higher its length-to-beam number, the higher a cats potential speed. While not all designers provide the waterline beam information to make accurate comparisons, approximated figures can be instructive.

We took a sample of five cruising cats and found only the relatively bulbous Prout 38 to have a length-to-beam number as low as the Seawind 1160s ratio of 7.7. Beamier hulls make for a greater payload and a higher prismatic (which is good). However, they limit top-end speed while adding parasitic drag that harms light-air performance.

Wards formula for fun under sail includes a powerful, big-roach, fully battened mainsail. Trimmed via a traveler atop the targa, the sail is both powerful and simple to control. The high-aspect ratio jib is an efficient adjunct with maximum lift developed by its long leading edge and efficiency born of good trimming angles. The latter emanate from the 1160s simple-but-elegant self-tacking arrangement (an arc of track on the foredeck with blocks and fairleads positioned to provide even tension through a good range of orientations). The octane in the tank can come from an optional screecher. Flown from the boats fold-down sprit, it can supercharge apparent wind and energize the speedo.

Catamarans have an aesthetic unto themselves. The 1160 has sharp, near-plumb stems that slice attractively through the water. Its transom curves are sinuous and long. In between, we find elements that fail to mesh. Its black glass hull windows seem automotive, but help reduce glare. Its hard-topped saloon with oversized windows smacks of a powerboat. Granted, these observations are from the eye of the beholder, but we have beheld better-looking boats.

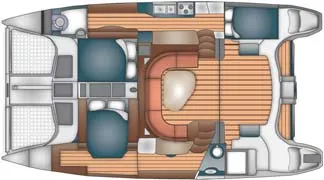

Accommodations

Due to its oversized hull windows, the 1160 is exceptionally bright belowdeck. The hulls are open well forward from the stairways descending both port and starboard. The molded glass interior is relieved in places with accents of wood, but in our opinion, the impression was more stark than traditional and shippy.

To port is an inward-facing nav table, a generous double berth, and a spacious head. The heads stand-up shower compartment (behind plexiglass doors) has much more elbow room and convenience than sailors are generally used to.

One optional layout features an athwartships island double (on the port hull only), which allows access from both sides of the bunk. Air-conditioning ducts are in place, and you can open overhead hatches, but the fixed side windows don’t allow for any cross ventilation. Another choice is a four-cabin layout with doubles at the ends of each hull and a second head instead of a nav station. The after cabins in this set-up appear tight with berths that are not much over six feet, but inward-facing opening ports and standard fans make for better ventilation.

Grey Polystone counters (inboard and outboard) provide an exceptional amount of work space in the galley. The three-burner propane stove and double stainless steel sinks are top quality and appropriately sized. There is a front-opening refrigerator as well as a deep freezer (2 cubic feet).

Despite the boats outdoorsy feel and the serious stainless gas barby located on the aft deck, the 1160 galley-ample stowage, teak and holly sole, varnished cabinetry, and deep cutlery drawers-seems well set up for preparing real meals. The downside, of course, is shuffling dishes up and down to the main saloon, typical on cats this size.

Belowdecks accommodations suit the 1160 for cruising and even passage making, but the heart of the boat is the cockpit/saloon area. While the table lowers to become a double bed, thats hardly the extent of the boats versatility. With the remote for the autopilot, you can steer in protected splendor. On the other hand, if you want to entertain 22 or so of your most-intimate friends dockside, youve got the space to party (without even disturbing those in their bunks below).

Performance

Theres nothing particularly scientific about it, but when you see the competition disappearing astern, its bound to give you a good feeling about your boats performance. Never mind that the cat in question was under cruising sail while we were sporting a screecher; adrenalin made us happy to be aboard the 1160 during our test sail following the Strictly Sail Show in Miami in February.

The rush of that encounter was about the only excitement, however. The breeze topped out at about 4 knots true. Other than admiring the way Seawind Sales Manager Brent Vaughan popped the full length battens in the main after a tack to remove the reverse camber in the sail, there was not that much to note. We did try the outboard helm positions and were pleased to note that we could see the tell-tales (drooping) clearly from the weather side. We did hoist the main and feel that, even with the 2:1 purchase on the halyard, it was a very big sail. We steered for a while and noted that, despite the lack of pressure on the helm, it was much harder to turn the wheel than we liked. (Vaughan agreed and took the problem to the shop: Weve actually re-designed that tiller system with pull-pull cables to minimize friction. It steers much better now, he reported.)

Finally some puffs rippled in, and we got the hulls burbling with enough momentum to try some tacking. We noted how easily the boat turned through the wind and how well it maintained its way despite changing boards.

Given the lack of distraction, we were able to scrutinize the sail controls. The self-tacking jib is simple and, even without much wind in the sail, did not appear to be overcome by excess friction. The mainsheet traveler system atop the targa is elegant and efficient. All cruising boats purport to be rigged for single-handed sailing. The Seawind 1160 makes that promise a reality.

With so little actual performance to go on, we tried to learn more about the boat. Many of those who have sailed the 1160 say that it tacks easily. This involves some rocker in the hulls, good-sized rudders, a shallow forefoot, and a well-modulated balance between the center of lateral resistance (below the water) and the center of pressure (in the sail). From what we saw, the 1160 fits these criteria fairly well. We think, therefore, that it will be that rare multihull that sails through a tack as positively as the average monohull.

Starting with the SW 1000, Ward has given his cats asymmetrical hulls. He builds in flare on the inside of the bows and carries it well aft (above the waterline). He gains interior volume this way, but he also asserts that the shape cushions the boats ride and prevents both wave-slapping on the bridgedeck and pitch-poling in waves.

Delivery skippers we have consulted are positive about the boats performance. She doesn’t dive or sail around the leeward bow the way most multihulls do, one veteran said. On the other hand, a naval architect noted for multihulls says that any strake or flare has to counteract something like 50,000 foot pounds of force. I doubt that a bulge in the hull can do that. We must admit that this is a question weve yet to answer.

The 1160 is powered by twin Yanmar diesel (30 hp) saildrives. The noise and vibration levels were remarkably low throughout the boat, even at high rpms. Twin-screw maneuverability is a solid advantage that boats like these present. It was slightly difficult to access the engines: For example, accessing the dipstick via a panel in the head seemed convoluted.

Conclusions

We especially liked the open feel of the sailing/living area on the 1160. The big, integrated cockpit/saloon is a wonderfully accommodating space that does what Ward says it does-bring people together. The tri-fold doors used to button her up are ridiculously simple. Were not saying that makes them foolproof, but they should work well.

Looks left us cold, as we have said. Style-as in carpeted patches below, lackluster woodwork, less-than-imaginative decor-we found to be a weakness. But that, too, can be a matter of taste. The boat costs over $400,000, but in many areas, it doesn’t look like it.

There are some good things about a catamaran built for comfort, not for speed. We doubt that the Seawind will suffer materially from overloading; it is not that close to the cutting edge of performance to begin with. Having heard reports of an 1160 weathering a three-day storm in the Tasman Sea, we are further convinced that it is put together well. We have faith that High Modulus will guide the process so that it becomes even better built.

Ward has been, for more than 30 years, a pioneer. Hes opened eyes, raised questions, and changed minds. While the 1160 shows a creative approach to meeting market demands, its hard to see it as Wards supreme achievement.

Contact – Seawind Yachts, 61 2/9810-1844, www.seawindcats.com.