During the 1950s, Robert Clark, an amateur woodworker with a degree in education and a teaching certificate, labored in Toledo, Ohio as a pattern maker in the auto industry. He had a creative mind, and made prototypes that eventually became standard equipment on automobiles – dashboards, for instance. He passed spare hours building Lightnings and Thistles in a garage, and was among the first to construct boats using fiberglass.

Tiring of the corporate grind, Clark moved his family to Renton, Washington, to pursue his dream of operating a sailboat manufacturing company. In 1960, he established the Clark Boat Company. As the company endured the financial struggles associated with the fledgling business, Clark’s wife, Cora, made the money to put bread on the table, and sons Don, Dennis, and David chipped in free labor in the plant after school hours and on weekends.

Dennis describes the factory as a “ramshackle old building” opened in concert with Axel Olsen for the purpose of building OK dinghies and Optimists. Olsen was a bricklayer and sailor from Denmark who had apprenticed with Paul Elvström.

The company eventually established itself as a place for do-it-yourselfers to complete construction of home-built daysailers. “We could have 15 boats in varying stages of construction at any one time,” said Dennis.

Despite being a nondescript builder whose budgets did not allow it to advertise in national magazines, the company prospered. When the OK Dinghy business burgeoned, the shop was moved to larger quarters, and Clark, with a new partner, Bud Easter, began building other boats like the I-14, Thistle, 505, and Lightning. They also built Stars for Olympic gold medal winner Bill Buchan, who became Dennis’ mentor.

After graduating from the University of Washington with a degree in engineering, Don became the company designer. Among his first designs was a modified I-14 that became the Sea Lark. By the late 1960s, the Clarks decided to enter the trailerable sailboat market, and introduced the San Juan 21, of which more than 3,000 were built.

After the company outgrew its 32,000-square-foot facility in Washington and was enjoying tremendous success in the East, Robert and Cora moved to North Carolina in 1969 to set up a second production facility. “We’ve since decided they were ready for a new adventure,” Dennis said.

During its heyday, Clark Boats employed 150 workers in Washington, and a similar-sized staff in North Carolina. Don doubled as designer and manager of production. He eventually designed the San Juan 21, 23, 7.7, 28, and a 26-footer that had a short lifespan. The SJ24 was a Bruce Kirby design with 4′ draft – a pocket rocket for racing under the IOR rule. On the technical side, the company was among the first to use vacuum bagging techniques.

Dennis oversaw the sailmaking and tooling operations. At one point, the company had the largest sail loft in the northwest, and was selling a third of its production to owners of non-Clark-built boats.

David was in charge of marketing.

During its ownership by the Clarks, the company produced approximately 6,000 San Juan models, and 2,000 dinghies. However, in response to the precipitous decline in the industry in the early ’80s, the North Carolina plant was closed. In 1986 the company was sold to an engineer who had no experience in the boatbuilding industry. The Clarks lent assistance for a year, during which the construction of San Juan boats was continued while the new owner attempted to convert the plant to a facility for the production of Valiants. However, Clark Boats eventually went the way of many endangered species.

Molds for various models are now owned by Gene Adams, who operates Port Gardner Sailboats, a company specializing in servicing and finding parts for SJ owners. He also is a member of a very active SJ21 one-design fleet.

Design

More than 300 San Juan 28s were built after its introduction in 1978. It became one of the most popular boats in the Clark line.

The SJ28 has a sporty look, with a downward sloping sheerline leading aft from a fine entry to a narrow, slightly reversed pinched stern (a la ’70s IOR shapes). The cabintop is also nicely raked and beveled, and is raised quite high aft, allowing good light and headroom down below. The high-aspect rig with small main and big foretriangle is also typical of the day.

Don Clark says the 28-footer was designed specifically to compete with the likes of boats manufactured by Ranger, Pearson, and Cal. Looking for the right combination of speed and comfort, he blended a quasi-conventional shape with a performance underbody, and produced a space below that provides 6′ 4″ of headroom.

“Her design was a takeoff from half-tonners, with a spade rudder, fin keel, and IOR-influenced underbody, but with the stern chopped off,” he said.

“She has a tall, powerful rig, 50% ballast ratio, and a beam that is offset by a deep fin keel and powerful, balanced spade rudder.

“She has a conservative rig, but is on the fast side of cruising. She was designed to sail extremely well in light air.

“She has good windward performance, and is well-behaved. She carries no weather helm. But she can be just short of a handful downwind for the inexperienced sailor.”

A year after her introduction, the SJ28 finished second at Yachting’s One-of-a-Kind-Regatta in Annapolis, finishing only behind a San Juan 24.

Following the sale of the company, Don spent three years cruising before landing in San Diego, where he operated a chain of bike shops. He’s now a custom cabinetmaker.

Deck Layout

Step aboard the SJ28 and the first impression is that the cockpit is small and well-organized. A tiller occupies the center of the space, and this motivated many owners to change to wheels. The traveler is located at the companionway and the mainsheet tackle is fastened directly to the end of the boom. Since the boom is only 5’8″ above the sole, crew will learn quickly to protect their noggins on a tack or jibe.

The arrangement allows the helmsman to trim the main – a sensible arrangement on just about any boat. However, the traveler location, also common, can be highly inconvenient with people traveling through the companionway. Many a finger has been pinched in travelers here, and many a lock of hair lost in the mainsheet tackle.

From the outset, halyards, reefing lines, and vang controls were led from the base of the mast to winches atop the cabin. While that’s now a standard arrangement on production boats, it was a layout employed primarily by singlehanders in the 1970s.

The cockpit will seat four adults comfortably. From a cruiser’s standpoint, a smaller cockpit reduces the risk of swamping, though the boat is not considered a candidate for bluewater cruising.

Cockpit seats are 16″ wide, 14″ high, and 6 feet long, and the footwell allows good legroom. Cockpit storage is compromised by a starboard quarterberth that reduces the size of the starboard lazarette to a long shallow tray that is susceptible to the accumulation of water in drippy weather. A port locker provides a larger storage area and room for two batteries.

The owner of our test boat replaced the original alcohol stove with a propane unit, and built a properly vented tank locker aft of the port locker. This was a good installation; however, newer alcohol stoves are much safer and more efficient than the old pressurized models, so double-check before applying a saw to the fiberglass.

Jib sheets are led to winches aft of the helmsman where trimmers and grinders will have reasonable elbow room. Close sheeting for headsails is on tracks located alongside the cabin. Snatch blocks for downwind sails can be attached to holes in the aluminum toerail.

The single-spreader rig with in-line spreaders is typical of boats of this era. Swept-back spreaders might have allowed slightly better sheeting angles, but Clark decided on simplicity and stability. Owners report no wire failures, though some have replaced the standing rigging after 20+ years.

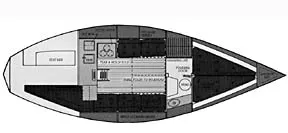

Belowdecks

Spaces belowdecks reflect the types of interiors that were produced during the early stages of an industry transitioning from all-wood, handcut joinery to combinations of wood and fiberglass. The interior is defined by a white liner accented by a teak-andholly sole, wood bulkhead and cabinets, and white laminates on countertops. Cupboard doors were constructed of woven cane enclosed in teak frames.

The 10-foot beam and 6′ 4″ headroom gives generous space in the saloon for a boat with a 22′ 4″ waterline, especially when the bulkhead- mounted table is stored out of the way.

In its standard configuration, the L-shaped galley is located to port at the foot of the companionway, aft of a short settee. There’s a full-length settee (7′ 4″) to starboard, forward of the quarterberth. The settee slides out to make an undersized double berth that two adults will find a tad narrow.

The head is located between the saloon and V-berth.

Both settees have 10″ shelves outboard of the cushions. This kind of stowage was once common, but is now usually eliminated in newer boats in favor of wider accommodations. Think of it – there’s no space dedicated to an entertainment center…

The galley has countertops 52″ and 25″ long, including space over a dry locker. The two-burner stove swings athwartships to ease cooking chores when on the wind. A modicum of storage is located under the single stainless steel sink and outboard of the stove.

The head compartment is small, with toilet, fiberglass sink, and 10″ vanity sandwiched into the space.

The length of the V-berth on the centerline is 66″, and it’s 66″ wide, so will sleep two adults. Storage is below the cushions, on two shelves lining the hull, and in a hanging locker. A six-gallon holding tank is located under the berth.

Standard gear included a diesel heater, since this is a northwest boat designed for year-round use. Original equipment also included a panel with five switches, so new owners adding navigational instruments should plan on adding new circuits.

Fuel is located in an aluminum tank under the quarter berth, water in a 20-gallon plastic water tank under the galley sink. Engine access is 270 degrees from the starboard quarter and under the companionway steps. Access to the aft end will be a challenge for anyone larger than a Lilliputian, since it’s via a tiny space in the lazarette.

On balance, potential buyers will find the spaces where most time is spent belowdecks to be adequate. The dining area is large enough for 4-6 people; berths are adequate for three adults to sleep comfortably. The quarter berth is 80″ long and only 28″ wide. This actually makes for a comfortable, secure sea berth, although in harbor more elbow room would be nice. On our test boat it served as the equivalent of a hall closet. The port settee is long enough for a child.

Construction

Our test boat is used by an owner who spends weekends on the racecourse or cruising with a family; it’s not a dockside entertainment center. During three hours aboard we saw little evidence of cracks in the gelcoat, or crazing where hardware had been installed. The gelcoat topsides were still in good shape.

Dennis Clark described the layup of Clark Boats as consisting of “high-quality gelcoat with a skin coat of cloth, or mat, plus roving.” Hulls were solid fiberglass, hand-laid. Hull thickness at the bottom is 7/16″; topsides are 3/16″.

“Sheets of mat were used, along with small amounts of chopped mat laid by hand between the roving,” said Clark. “Few of our boats had blister problems.” A PS survey of owners found few who experienced blister problems. The majority that occurred were small, and repaired by owners at a cost of $300 or less.

Decks were cored with balsa, and, in areas where hardware is fastened, with marine plywood.

The hull-deck joint is an inwardturning flange on which the deck sits; the two sections were bedded in polysulfide. The solid glass toerail was secured through deck and hull with screws on 6″ centers.

One shortcoming of the manufacturing process was the installation of a partial bulkhead to port, to which the chainplate is attached.

“That chainplate may leak, and that section is susceptible to rot,” Dennis says. As they became aware of the problem after the first batch of boats were produced, the Clarks provided owners with a repair kit. Close inspection of the area by owners and potential buyers should be high on a survey and maintenance checklist.

Common complaints among current owners are an ongoing need for inspection and rebedding of leaky hull-deck joints and chainplates; a few owners commented about leaky ports.

Performance

We sailed the SJ28 in winds ranging from 5 to 15 knots, and once again noted the inaccuracy of the idea that moderate-displacement boats won’t sail in light air. Some do. This one does.

With owner Willie Gravley at the helm and Gene Adams trimming sails, we sailed near the Strait of Georgia with a Dacron main and 150% genoa on a roller furler.

In addition to feeling buoyant, though not nimble, she sailed as close to the breeze as Gravley’s previous boat, a 1977 Catalina 27. It was a switch that produced an increase in speed without loss of creature comforts or the need to incur a large debt.

Though Gravley is performance-oriented, the boat needs only stores and bedding to be ready to head for a cruise to Canada’s Gulf Islands.

At windspeeds of about 5 knots, boatspeed hovered between 2.9 and 3. 5 knots as we sailed into a small chop with the headsail six inches off the spreader. However, a key to maintaining steerage in light air is to sail her loose, following the adage, “When in doubt, let it out.” To demonstrate her balance, Adams set main and jib, Gravley stepped away from the tiller, and she sailed herself.

With wind at 6 knots, boatspeed increased to over 4 knots on the beat. She tacked through 90-100 degrees. Sailing on a reach with 5 knots of wind speed, she sailed at 4.5-5 knots.

Finally seeing puffs of 11 knots of breeze, boatspeed increased to 5 knots beating to weather. We footed off, hoisted the spinnaker, and headed downwind.

A shortcoming of the SJ28 is that when off the breeze, the pinched stern that is so typical of IOR designs of the time can be a handful for the inexperienced helmsman. She could be squirrelly in a big sea.

With Gravley trimming the main, Adams on the spinnaker sheets, and windspeed holding at 8 knots, speed held at 6 knots.

The bottom line: this yacht will sail circles around many similarly sized sloops designed for the weekend cruiser that were built during the same generation. She’s surprisingly responsive in light air.

Conclusion

The SJ28 was designed and built by a company whose owners were performance-oriented and used to sailing boats to their limits. She displays good performance, even with an average sail inventory of conventional sails. The cockpit is large enough for four to six passengers, or a race crew, to sail with elbow room. It’s small for dockside entertaining.

More than 20 years after their construction, the living quarters in our test boat showed little sign of wear, despite the boat’s hard use as a racer and cruiser. There’s good headroom and cabin space, augmented by the ability of the saloon table to stow up against the main bulkhead.

Accommodations are best suited to a couple. Four or more can live aboard in a pinch. The galley is just large enough, the head small.

The SJ28 will respond to the needs of a veteran sailor, or small-boat sailor moving to a larger vessel. And she’s affordable: a patient buyer might be able to find a well-maintained boat for $12,000-15,000; or a fixer-upper for less.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Owner Comments.”

Click here to view “Used Boat Price History – San Juan 28 – 1982 Model.”

Contact – Gene Adams, Port Gardner Sailboats, 360/445-2814, www.Sanjuan28.org.

Hi, I have the SJ28. Can I remove wall between the toilet and the v-bert