Photo by Billy Black

305

In name alone, the new Presto 30, a shallow-draft cruiser designed by Rodger Martin has set the bar as high as it will go. The centerboard, round-bilge sharpie is named after Presto, the legendary 41-footer designed by Commodore Ralph Munroe and effusively praised by his friend Vince Gilpin in the 1937 book “The Good Little Ship.”

For the 21st-century fans of Munroe’s 19th-century design, Presto holds near mythical status. After sailing his Presto for six years from “Cape Cod to the Gulf Coast of Florida in all kinds of weather,” Munroe introduced the design to the public in the November 1926 edition of Yachting. It was 41 feet on deck, 10 feet, 6 inches in the beam, and had just 30 inches of draft. Ballast was some 4.5 tons of pig iron.

“Throwing out the old axioms that with light draft, one must have more beam, I did the opposite, reducing the beam at the deck, and still more at the waterline, but adding a little deadrise, and increasing the depth of hull and bilges to give ample displacement and righting moment,” Munroe wrote. “She was one of the most wholesome and satisfactory boats I ever owned.”

Martin’s Presto 30 is clearly a descendant of Munroe’s round-bilge sharpies, but the resemblance fades once you remove the rig. Using velocity prediction programs (VPP) to evaluate sailing efficiency, Martin re-thought the design and engineering of the traditional hull.

The sharpie profile—at least up to the sheerline—is easily discernible. The Presto 30 has a greater beam-to-length ratio than the original. The bow is finer, and the almost perpendicular, broad flat transom is a clear departure from Presto’s counter stern.

To some degree, how faithfully the boat holds to Munroe’s model is moot. Nearly every current designer who has dabbled in a shoal-draft cruiser has hailed Munroe’s Presto as inspiration, despite sometimes dubious connections. At the end of the day, the Presto 30 is a character boat, and Munroe is the name behind the character.

Although there is no shortage of sharpie-lovers, the market for “good little ships” is small—too small for most builders to bother. Fortunately, for Munroe fans, Martin makes his living designing ocean racers and fast cruisers; from its inception, the Presto 30 was a diversion, an indulgence in Martin’s passion for sharpies.

“This boat goes back to 1980, when we were sailing in the Exumas,” Martin recalled. “A strong northerly blew through, and we watched as this 32-foot sharpie sailed right up to the beach. I was impressed.”

With no buyers or builders clamoring for the ideal Exuma cruiser, Martin set his sharpie dream aside for a couple decades. Opportunity finally knocked in 2005, when the outdoor leadership school Outward Bound began looking for a boat to replace its aging fleet of Cy Hamlin-designed double-enders. Outward Bound’s design brief called for a boat that would be equally suited for its bases in Maine and in Florida, and Martin immediately thought of Munroe’s sharpie. Martin’s boat, based on Munroe’s round-bilge sharpie concept, was unanimously chosen from several bids and became Outward Bound’s new Hurricane Island 30. When interest in the Hurricane Island 30 led to requests for a cruising version, Martin went back to the drawing board and came up with the Presto 30.

The boat’s builder—Ryder Boats in Bucksport, Maine, best known for its tooling for high-end builders such as Hinckley—soon found itself with an unexpected blessing in a down economy: It was busy building Presto 30s. One year after the boat’s introduction in March of 2009, eight hulls have been built.

Design

The origins of the hull and rig date back to a classic American oyster-tonging boat, the New Haven sharpie, which first appeared in Long Island Sound sometime before 1850, according to American maritime historian Howard Chapelle. Various iterations appeared, but at the height of its popularity in 1880, the typical two-man New Haven sharpie was a 35-footer rigged with twin leg-of-mutton sails on sprit booms.

To create his round-bottom sharpie, Munroe effectively rounded and smoothed the “sharp” chines that gave the boat its name. Although the traditional-minded yachting journalists of the era derided anything but heavy-displacement, deep-keel boats as “skimming dishes,” these easily driven hulls offered a glimpse of the future, eventually leading to the planing dinghies and scows still racing today.

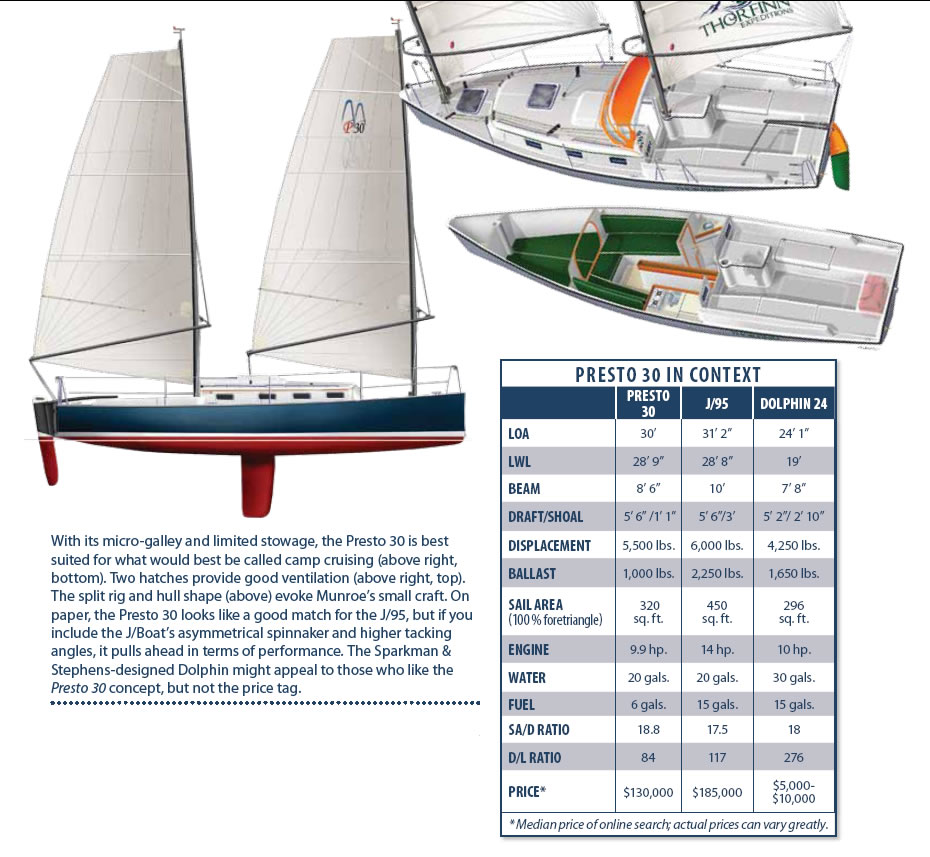

Trailerability and shallow draft were two of the most restrictive design details Martin had to work within when developing the Presto 30. Rules vary, but in most states, an 8-foot, 6-inch beam is legal width for trailering without any special permits.

Martin’s hull is 30 feet on deck with a waterline length of just less than 29 feet. Beam is right at the trailerable 8-foot, 6-inch maximum, about 2 feet narrower than an average 30-footer today. With the centerboard up, it draws just 13 inches, and with it fully extended, the draft is 5 feet, 6 inches. You can motor in about 2½ feet, and sail to windward in 3 feet. Internal ballast is 1,000 pounds. The total tow weight, loaded with gear and including the trailer, is about 6,600 pounds, requiring a full-size SUV with a towing package.

Like the original 1850 New Haven rig, the 320 square feet of sail area is divided between two full-batten sails on sprit-booms (wishbones). A performance package boosts sail area to 400 square feet. Although the identical masts suggests a schooner rig (which is what Martin calls it), the forward mast sits a little deeper in the boat, so Ryder calls the boat a cat-ketch. The result is the same. Not only does the low-aspect split rig aid stability by keeping the center of effort low, the sealed carbon-fiber masts add some buoyancy that further help it resist a full capsize. Martin’s stability curves give the Presto 30 self-righting capability up to 145 degrees. Although based on the accepted International Measurement System (IMS) for rating stability, this is an optimistic scenario that assumes that there is no down-flooding and includes the buoyancy of the sealed spars.

Munroe’s most famous sharpie in this size range, Egret, covered many offshore miles delivering mail along the Florida coast at the turn of the century.

Although the Presto 30 is light enough to be sculled, the hull’s primary mission is performance under sail, particularly when reaching. To dial the thrill meter up a notch, Martin stretched the waterline and gave the Presto a much flatter run aft than the Hurricane Island 30. Since he and Phil Garland (a principal in the carbon-fiber-spar specialists Hall Spars) were to be co-owners of hull

No. 1, performance priorities rose to the forefront.

Martin and his wife have been on two long cruises with the boat, once around the tip of Florida and this year, two months in the Bahamas.

“It’s turned out to be a very fast, handy cruising boat,” Martin said. “More than I imagined it to be, which is strange to say, since I designed it.”

Munroe expressed a similar surprise with Presto.

Deck Details

The long 10-foot, 6-inch cockpit offers plenty of room to stretch out or sleep under the stars. The boat is tiller steered, with a 2-inch-high, contoured foot brace running up the center of the cockpit. The foot brace helps crew keep to their seats when the boat is sharply heeling, but it also will keep them on their toes at anchor—at least until they learn to avoid it when moving about the large cockpit.

Owners have a couple of options for propulsion: a 12 horsepower inboard diesel with a folding prop, a stern-bracket mounted outboard, or a well-mounted outboard. The boat we sailed had the well-mounted outboard option. On our test boat, a fiberglass cutout that fit the well opening was fixed to the bottom of the outboard skeg. When the outboard was lifted for sailing, the well opening was essentially sealed, presenting a smooth, flush bottom for sailing.

A narrow, flat-bottom boat offers scan’t real estate belowdecks, so cockpit stowage becomes essential. The Presto 30 cockpit has three, well-gasketed latching lockers under each of the settees and a fourth mini-garage underneath the cockpit sole. The port locker is sized for a valise-packed life raft, while the starboard locker has room for buckets, rope, and fenders. The lazarette locker has about half as much storage as the port and starboard lockers. The sole locker is an ideal spot for big stuff like dive gear, folding bikes, or a roll-up dinghy. For those who don’t like transom ladders, a transom door is an option.

The helmsman accustomed to sailing sloops may complain about the way the mizzen mast splits his field of vision, but when the boat is running, the high wishbone booms allow much better forward visibility than you would find on conventional sloops.

When running dead downwind or nearly so, the rotating masts allow the wishbone booms to be winged forward of the beam, so you can effectively sail with the mizzen sail set to windward, and the mainsail to leeward. In smooth water, the boat balances extremely well with the sails set like this, out wing-and-wing. This is but one of the split rig’s many “sharpie tricks,” as Munroe called them.

All sail-trim controls are close at hand for the helmsman. Both sheets are double ended, putting them within easy reach on either tack. The mizzen sheet ends lead to twin cam cleats on the port and starboard cockpit coamings, while the mainsail sheet leads to cam cleats adjacent to the companionway.

Our chief complaint with the deck layout was the narrowness of the side-decks, a common trait among boats with narrow beams. This makes for a snug squeeze between the cabintop and the stanchions, and the big step down from the cabintop to the sidedeck should be avoided at sea. In our view, narrowing the coachroof to allow an extra inch or two on the sidedecks would be an improvement. On the plus side, the Presto 30’s coachroof is lined with stainless-steel handrails giving you plenty to grab on to as you move forward.

The boat features a generously sized divided locker for ground tackle, with two strong bits for securing the anchor. The stern cleats are amply sized, but they are mounted too low, so that the dock line chafes against the toerail.

Accommodations

Envisioned as a versatile, trailerable weekender that is capable of longer camp-style cruises, the Presto 30 has berths for four. Its tight quarters below and limited carrying capacity, however, suggest that couples or singlehanders would be a better fit for any longer cruises.

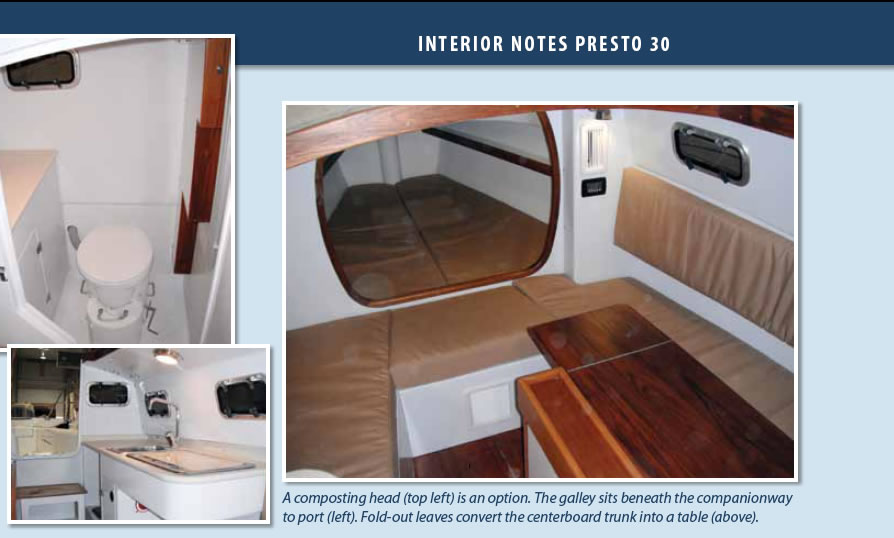

A curtain divides the 6-foot, 6-inch V-berth and the two 6-foot, 4-inch settees in the main saloon. The centerboard trunk splits the aft section of the narrow main saloon down the middle, and Ryder has cleverly converted this into a fold-out dining table. The centerboard trunk also offers a convenient place to brace yourself when moving about belowdecks.

The initial hull had a pop-top built in it, raising the 5-foot, 2-inch headroom to more than 6 feet while at anchor, but Ryder no longer makes that version. Sailors who want more headroom can opt for the new pilothouse model, which the company will be launching this summer.

The head, equipped with a toilet, a small sink, and a handheld shower is located aft to starboard. This makes a handy wet-locker for foul-weather gear. Owners can choose between a composting head or conventional marine toilet with a 12-gallon holding tank.

The boat we sailed had a fixed galley to port with a small sink, a double-burner alcohol stove, and slot for a cooler.

The boat we sailed was Thorfinn, an expedition model specifically designed for Thorfinn Expeditions. The company, which is owned and operated by Thor Emory, the former program manager for the Outward Bound Sea Program, runs adventure charters for small groups who want to explore Florida, Maine, and the Canadian Maritimes.

When we tested the boat on Pine Island Sound, near Naples, Fla., it had just finished a charter in the Florida Keys and was still loaded with all the equipment required for a guest charter, except for food provisions.

Thorfinn had already proven itself a fast boat, winning fourth place overall and second in its class on corrected time in the 2011 Fort Lauderdale to Key West race. Thorfinn, which had the shortest waterline of any monohull in the race, covered the 160-mile course in 22 hours.

After struggling in the light winds at the start of the race, Thorfinn (which carried a PHRF rating of 164) showed what a boat with minimal wetted surface can do downwind. In the 20- to 25-knot northerly, Thorfinn hunted down all but one boat in its class, beating a Hunter Legend 37, a C&C 33, and a Hunter 35.5 on uncorrected time. Emory’s blog account of the sail posted on the Thorfinn Expeditions website describes surfing down waves at speeds up to 14 knots.

The day we sailed the Presto 30 brought more typical winds. One of the obvious advantages of the unstayed sharpie rig is the ease of maneuvering under sail. No preventers, vangs, or runners to deal with. No jibsheets to mess with when tacking or jibing. And the booms are well above noggin height, alleviating concerns about concussive blows during an accidental jibe.

The boat’s nimbleness came in handy when the foam windscreen for a video-camera microphone blew into the water during the test sail. We recovered the piece, which is about the size of a dime, in one pass under sail. The entire recovery maneuver (a modified deep-reach-and-return) took less than a minute.

Tacking angles were better than expected from the rig, about 45 degrees. The Presto 30 will not point as high as a sloop, but when you crack off about 5 to 10 degrees, the boat foots along nicely.

We spent most of the afternoon reaching in calm waters at about 5 to 5.7 knots until the sea breeze picked up to about 12 knots after lunch. Reaching with the staysail flying from the main mast kept the boat moving at 6.7 to 7.2 knots for the run back to Pine Island Marina.

The most rewarding sailing was on a beam reach with the true wind between 80 and 115 degrees. When we set the staysail off the wind. it added more than a knot to overall boat speed. The boat was well balanced under sail, although Emory says he eases the main some in higher winds to decrease weather helm. The wishbone rig allows basic control of sail shape via the snotter-line, the line at the front of the wishbone that allows you to instantly adjust the draft in the sail. Racing sailors will gripe about the relatively limited control of sail shape and twist, but that is one of several tradeoffs that come with the rig. The boat was particularly well balanced off the wind, sailing by the lee with the sails wing-and-wing.

The one notable problem we had on the water was with the rudder design. When the rudder was kicked up for shallow-water sailing or motoring, the force of the water against the long rudder blade (unbalanced when raised) made it quite difficult to steer. The original New Haven sharpies had long, balanced rudders that were oriented horizontally, instead of vertically, requiring little effort to steer. The stock could be raised and lowered according to the depth of the water.

The new version of the Presto 30 will have a foil rudder in a cassette that will allow it to be raised and lowered without dramatically upsetting the rudder balance. The blade will still kick up in shallow water.

courtesy of Ryder Boats

327

Conclusion

Despite the optimistic numbers for stability, the fact remains that a narrow, shoal-draft sailboat is initially tender. The 1,000 pounds of lead shot encapsulated in the bottom of the boat and a low-aspect rig help offset the Presto 30’s handicap in this area, but like any light displacement boat, it will require an attentive hand at the helm in a blow.

One of the reasons to buy a shoal-draft boat is so you can avoid the nasty stuff, sail inland waters and nose into the sand or reeds when the weather turns foul. And should the weather catch you off guard in Albemarle Sound, the bob-and-weave abilities of a light displacement boat can be an asset in the right hands. Add the crash bulkheads, sound engineering and good construction and you have further reassurance off soundings.

For sailors in the Gulf of Mexico, the Carolinas, or the Chesapeake, where a shallow draft opens up a whole new world of cruising opportunities, the Presto 30 makes a versatile coastal cruiser. It also makes sense for the shallow-water adventurer looking for an expedition platform that can be trailered from the Gulf of Mexico to the Canadian Maritimes. And for experienced sailors like Martin, it makes a great Bahamas getaway, with a shoal draft that lets you tuck into places few sailors ever see. If performance is what you are after, you may want to look at the J/95, which is a less portable, but quicker shoal-water sailer.

Fully rigged and with a trailer, the Presto 30 sells for $142,500, and this is quite a lot to pay for 6,000 pounds of boat. No doubt a big part of the boat’s appeal is the romance of its storied heritage. While a modernized Presto-type sharpie may be an impractical choice for the average sailor, the Presto 30 fits a growing niche. It is encouraging to see builders and designers of this caliber exploring the exciting possibilities for a shoal-water cruising boat.