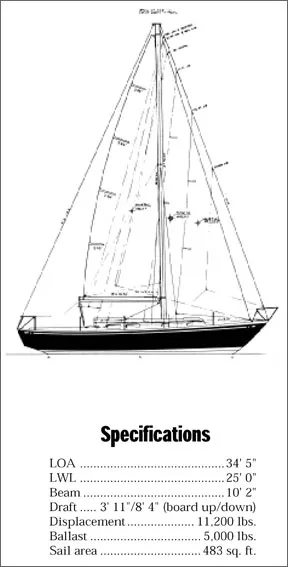

It may be hard to believe, but it’s been about 25 years since Olin Stephens designed the breakthrough 12 meter sloop Intrepid. Just a year later, he designed the Tartan 34, a keel/centerboard, CCA racer/cruiser, for Douglass & McLeod Plastics, the company that became Tartan Marine.

The CCA was a true racer/cruiser rule. Heavy displacement was encouraged, and keel/centerboarders were treated more than fairly, as the success of designs such as S&S’s Finisterre shows. Even top racing boats had real interiors—enclosed heads, permanent berths, usable galleys. You could buy a boat like the Tartan 34, and given good sails and sailing skills, you could actually be reasonably competitive on the race course. And then a couple could take their racing boat cruising, without a crew.

This was no “golden age” of yacht design, however. Interiors were unimaginative and fairly cramped. Galleys were small, and few boats had such amenities as hot water, gas cooking, refrigeration, and showers—things that are taken for granted today. Navigation stations were rudimentary. Sail-handling gear, by modern standards, was almost a joke. There were no self-tailing winches, few hydraulic rig controls, and roller-reefing headsail systems were primitive. Mylar and Kevlar were off in the future, loran was expensive and hard to use.

Yet some boats from this period, for all their “shortcomings” by modern standards, are classics in the truest sense: the Bermuda 40, the Luders 33, the Bristol 40, the Cal 40. And the Tartan 34.

More than 500 Tartan 34s were built between 1968 and 1978. By 1978 the CCA rule was long gone, PHRF racing was beginning to surge, and the MHS (now IMS) was in its infancy. The Tartan 34 had passed from a racer/cruiser to a cruiser, not because the boat had changed, but because sailboat racing had changed. The Tartan 34 was succeeded by the larger, more modern Tartan 37, a boat of exactly the same concept.

The boats are widely distributed in this country, but there are large concentrations along the North Atlantic coast, the Chesapeake, and in the Great Lakes. You’ll find them wherever the water is shallow.

Read this and weep: in 1970, a Tartan 34, complete with sails, cost about $22,000. By 1975, the price had gone all the way up to $29,000. Today, equipped with more modern equipment, the boat would cost $100,000 to build.

Sailing Performance

The Tartan 34’s PHRF rating of about 168 to 174 is comparable to more modern fast cruisers of similar displacement, such as the Nonsuch 30 and Pearson 31. The boat is significantly slower, however, than newer cruiser/racers of similar length but lighter displacement, like the C&C 33.

Like most centerboarders, the Tartan 34 is quite a bit faster downwind than upwind, and the boat can be run downwind more effectively than a fin-keeler. For example, in only 16 knots of true wind, optimum jibe angle is 173—about 5 ƒnlower than the typical modern fin-keel boat.

Because of her shoal draft, the boat’s center of gravity is fairly high. Righting moment at 1 ƒnis about 630 ft/lbs—some 20% less than a modern fin-keel cruiser/racer of the same displacement. This means that the Tartan 34 is initially more tender than a more modern deep-keel boat.

As first built, specifications called for 4,600 pounds of ballast. That was increased to 5,000 pounds on later models, although the boat’s displacement is not listed by the builder as having increased with the addition of the ballast. We’re not sure where the 400 pounds of displacement went.

The boat originally had a mainsail aspect ratio of about 2 1/2:1, with a mainsail foot measurement of 13′. The mainsheet on this model leads awkwardly to a cockpit-spanning traveler just above the tiller, well aft of the helmsman. An end-of-boom lead was essential because of the old-fashioned roller-reefing boom. This traveler location really breaks up the cockpit.

Although a tiller was standard, you will find wheel steering on many boats. Owners report no particular problems with either tiller or wheel. In both cases, the helmsman sits at the forward end of the cockpit.

With the introduction of the IOR, mainsail area was penalized relative to headsail area, and the main boom of the Tartan 34 was shortened by about 2 1/2′. This allowed placement of the traveler at the aft end of the bridgedeck, a far better location for trimming the main, which was still equipped with a roller-reefing boom.

Neither the base of the foretriangle nor the height of the rig was increased to offset the loss of mainsail area. According to some owners, the loss of about 35 square feet of sail area can be felt in light-air conditions. At the same time, shortening the foot of the mainsail did a lot to reduce the weather helm the boat carries when reaching in heavy air. Some boats with the shorter boom have made up the missing sail area by increasing jib overlap from 150% to 170%, but this lowers the aspect ratio of the sail, costing some efficiency.

We would recommend a compromise on boats with the roller-reefing boom. When the time comes to buy a new mainsail, get a new boom equipped with internal slab reefing, internal outhaul, and stoppers at the inboard end of the boom. If it’s not already there, install a modern traveler on the bridgedeck. Instead of going with either the short or long mainsail foot, compromise on one of about 12′. A modern, deep-section boom would not require that the mainsheet load be spread out over the boom. You could sheet to a single point over the traveler, about 2′ inboard of the end of the boom.

A major advantage of a centerboard is that the lead (the difference in fore-and-aft location between the center of lateral resistance of the hull and the center of effort of the sailplan) can be shifted as the balance of the boat changes. Tartan 34 owners report using the board to ease the helm when reaching in heavy conditions.

Like almost all S&S designs, the Tartan 34 is a good all-around sailing boat without significant bad habits. Owners who race the boat say that she should be sailed on her feet: at an angle of heel of over 20, the boat starts to slow down and make leeway. USYRU’s velocity prediction program disagrees, saying that the boat should be sailed at higher angles of heel upwind and reaching in wind velocities of 14 knots or more.

Since the boat is relatively narrow, the position of the chainplates at the deck edge is not a serious handicap for upwind performance. With single spreaders and double lower shrouds, the rig is about as simple and sturdy as you get. A yawl rig was optional, but most boats are sloops.

Engine

Like other auxiliaries of its era, most Tartan 34s are powered by the Atomic 4 gasoline engine. Beginning in 1975, the Farymann R-30-M diesel was an option. Either engine is adequate power for the boat, but it is not overpowered by any stretch of the imagination.

The Atomic 4 is a smoother and quieter engine.

Those Atomic 4s are starting to get old. On a boat you plan to keep for more than a few years, the expense of switching over to a diesel can be justified. The Universal Model 25 is a drop-in replacement for the Atomic 4 in many cases, but check carefully to make sure there is enough room, since the Atomic 4 is one of the world’s smallest four-cylinder engines.

The engine location under the port main cabin settee is a big plus, with one exception: since it’s in the bilge, it is vulnerable in the case of hull flooding. Almost everything else about the installation is good. The engine weight is just aft of the longitudinal center of bouyancy, where its effect on trim and pitching moment is negligible. By disassembling the settee, you have complete access to the engine for servicing and repairs, and you’ll be sitting in the middle of the main cabin, rather than crunched up under the cockpit. The shaft is short, minimizing vibration. There is no external prop strut to cause alignment problems, create drag, and possibly come loose from the hull.

At the same time, clearance between the prop and the hull is minimal, so you can’t go to a much bigger engine and prop. Because the prop is located far forward, the boat is difficult to back down in a straight line, and prop efficiency is reduced because the prop is partially hidden behind the trailing edge of the keel to reduce drag.

Some boats that race have replaced the original solid prop with a folding one, but if you mark the shaft so that you know when the prop is lined up with the back of the keel, the drag of the solid prop should be virtually indistinguishable from that of a folding prop. For best performance under both sail and power, we would choose a feathering prop if we had money to burn.

Original drawings show a 21-gallon gas tank located under the cockpit. Later boats have a 26-gallon fuel tank under the port settee in the main cabin, where the weight of fuel will have minimal effect on trim and pitching.

Construction

Tartan is a good builder, and the basic construction of the Tartan 34 is sound. There are, however, some age-related problems that show up repeatedly on our owners’ surveys. The most common of these is gelcoat cracking and crazing of the deck molding, particularly in the area of the foredeck and forward end of the cabin trunk.

A related problem that some owners mention is delamination of the balsa-cored deck. Modern endgrain balsa coring is pre-sealed with resin by the manufacturer to prevent resin starvation when the core is actually glassed to the deck. A cored deck depends on its solid sandwich construction for rigidity. If there are spots where the core and deck are not completely bonded, the deck will yield in this area. This is what is referred to as a “soft” deck. As the deck flexes, the relatively brittle bond between the core and its fiberglass skin can fail, so that the “soft” areas grow. This is very common in older glass boats.

A very careful survey of the deck should be conducted when purchasing a Tartan 34. This will include tapping every square inch of the deck with a plastic mallet to locate voids or areas of delamination. Minor areas of delamination can be repaired by injecting epoxy resin through holes in the upper deck skin. Large areas of delamination may be cause for rejection of the boat, or a major price reduction.

Another frequently-mentioned problem with the Tartan 34 is the centerboard and its operating mechanism. Unlike many centerboards, this one secures positively in whatever position you set it—it won’t freely pivot upward if you hit a rock. Centerboard groundings are extremely common, as it’s very easy to forget that the board is down.

One construction detail on a boat of the general quality of the Tartan 34 is disturbing. On early boats, through hull fittings consist of brass pipe nipples glassed into the hull, with gate valves on the inside. This is acceptable on a boat used only in fresh water, since there won’t be any galvanic corrosion. In salt water, however, this is an unacceptable installation. Brass pipe contains a lot of zinc, and it will disappear from the pipe nipples and gate valves just like your shaft zincs corrode away. Due to the age of the boats, these fittings should be immediately replaced with proper through hull fittings and seacocks, either of bronze or reinforced plastic.

Many deck fittings are chrome-plated bronze, and particularly on boats used in salt water, the chrome is likely to be pitted and peeling. Fortunately, this is a cosmetic problem, and you can get the stuff re-plated if you really want it to look good.

According to owner reports, the Tartan 34 has had an average number of cases of bottom blistering. That’s pretty good for boats of this vintage.

There’s a lot of exterior teak on the boat, including teak cockpit coamings, forward hatch frame, handrails, and a high teak toerail. On some boats we have looked at the toerail is kept varnished, but it isn’t easy to keep varnish on a piece of teak that periodically gets dipped underwater.

The electrical system is pretty primitive, with a 30-amp alternator, fuses instead of circuit breakers, minimal lighting.

Over the years, most of these boats have added gear such as navigation electronics, more lights, pumps, and probably a second battery. We would carefully examine the electrical system, since pigtailing additional equipment onto a basic system can result in horrible installations.

Interior

If you want three-cabin interiors and condo-like space, you’re not going to like the interior of the Tartan 34. This is not a floating motor home. It is a sailboat, and it has an interior layout that is as traditional as they get.

There is no pleasure-dome owner’s cabin, shower stall, or gourmet galley. Even the nav station is rudimentary—a drop-leaf table at the head of the quarterberth.

There are fixed berths for five in the original arrangement and the port settee extends to form a double. In later boats, lockers outboard of the port settee were replaced with a pilot berth. This may be a better arrangement for racing, but you don’t need that many berths for cruising.

We wouldn’t want to spend more than a weekend on the boat with more than four adults, and we wouldn’t cruise for a week or more with more than two adults and two well-behaved children. But then we wouldn’t do that on many boats less than 40′.

On the plus side, all the berths are long, including a 7′ quarterberth. Even the forward V-berths are wide enough at the foot for big people.

Good headroom is carried all the way forward: 6′ 2″ in the forward cabin, a little more aft.

The cabin sole is pretty much level throughout the boat, except in front of the galley dresser and quarterberth.

The cabin sole is cork, an unusual feature. Cork is a good natural insulator, and provides great traction underfoot. It does, however, absorb dirt and grease, and it’s difficult to keep clean.

Interior finish is typical of boats of this period: pretty drab, pretty basic. There are no fancy curved moldings and rounded laminated door frames. The original finish in early boats is painted plywood bulkheads with oiled teak trim. You can dress this up a lot by varnishing the wood trim. On later boats, the main bulkheads are teak-faced plywood, while the rest of the flat surfaces are white laminate.

There is a drop-leaf main cabin table, covered with wood-grained plastic laminate. Whoever invented wood-grained plastic laminate should be consigned to an eternity of varnishing splintery fir plywood with a foam brush on a foggy day. We’d rather see an acre of white Formica than a square foot of wood-grained plastic laminate, no matter how “real” it looks.

Because the fuel tank, water tanks, and engine are located under the main cabin settees, there’s no storage space in these areas. Storage space in the rest of the boat is good, although hanging space for clothes is limited.

Water capacity is 36 gallons. This is inadequate for a boat that will cruise for more than a week with two people.

Like most boats from this period, the galley is small, consisting of a two-burner alcohol stove, an icebox with mediocre insulation, and a single sink. Original specifications called for a stove with no oven. Many boats by now have been upgraded to more modern cooking facilities—a must if you plan any real cruising.

The icebox is large, tucked under the starboard cockpit seat, and accessible from both the galley and the cockpit. It is difficult to reach into the box from the galley, since you have to stretch over the sink, and it has a vertical door rather than a horizontal hatch.

Conclusions

Given the shortcomings of boats such as the Tartan 34, why would you want one? There are lots of reasons. The boat is well-designed and well-built. With modern sailhandling equipment, two people can easily manage the sailing, and the boat will be reasonably fast.

The boat is seaworthy, the type of boat we’d choose for cruising someplace like the Bahamas. With minor upgrading, she is suited to reasonable offshore cruising.

Oh, yes, don’t forget. This is a good-looking boat, a real classic. With freshly-painted topsides and varnished teak, she’ll still turn heads anywhere. And that means a lot to a real sailor.

I have sailed my 1974 Tartan 34 C solo from New Port , RI to Culebra, PR. I am going to haul out my boat at Isleta Marina in Fajardo PR, to repaint my bottom and above water line. I broke off the bottom 2 feet of the swing keel a couple of years ago, so hoping to find a used swing keel to replace it. A new one from Tartan mfg cost $2,800. I look forward to taking the boat down through the leeward & windward islands winter season 2022. I enjoyed your review of the Tartan 34 C.

Hello Leslie: I own a Tartan34C also…………I bought it new in 1974 hull#269, although it has a 1973 date on hull. I still have it and I think I am going to use as a coffin……..yes….. I am an old bastard. It has been a terrific boat. I wish it did not have all of the teak trim…..to much time to maintain it……but that’s what makes it look good. Has the atomic 4 and I have rebuilt it two times. Good motor…….simple!!!!!!! Sounds like you are having a good time……HAVE FUN!!!!!!!!!! Jeff White PS……raced it many years ago…….1st Annapolis to Bermuda mid 80’s ……3rd Annapolis to Newport the first year race open to PHRF. Lots of Chesapeake Bay racing.

I crewed a 34 several times in the early 70’s. Previously the I-LYA Sears quarter final winning skipper in 1968, in a new club owned Thistle my Dad and I picked up that July at the original Douglas & McLeod works in Grand River OH. Our family then owned a D&M Highlander built of molded mahogany ply in the autoclave process. Only in this past year or two was the D&M business sign taken off the building, 90 minutes from our house and across the street from our periodic visits to Brennan’s Fish House. My crewing on the 34 included stints at the helm in moderately rough weather and I’d love to finish my sailing years on one if all the stars aligned for us to buy and maintain one today. Incidentally, in 1970 that new purchase price was about 2 1/4 times US median family income. By this article’s 2021 date, the article’s quoted new purchase price was down to only 1.48 times US median income.