If you’re looking for a good buy in a weekender, it pays to buy the brand. There will always be compromises when it comes to older boats—soft decks, tired cordage, weak sail inventory—but affordability is what we’re after, especially if it comes with a respected name. There are plenty of Tartan lovers out there, and the Tartan fleet has held up well over the decades. We concentrated here on the Tartan 30, part of a whole class of plus-or-minus thirty footers that emerged during a remarkably active period of production boatbuilding. In this day and age of internet listings, there are millions of pixels devoted to this size range. We found a few beauties (see sidebar, below).

The early 1970s was the heyday of the 30′ racer/cruiser. The phenomenon was not a coincidence. The Midget Ocean Racing Class (MORC) with a maximum boat length of 30′ had become highly popular. The IOR Three-Quarter Ton Class (a “poor man’s One Ton Class”) had just been formed. And most persuasive of all, a 30′ boat could offer eager boat buyers what they thought they wanted: five or six berths, full headroom, fully enclosed head, complete galley, and big boat heft. Better still, the rapidly maturing fiberglass boatbuilding industry was ready to produce such boats.

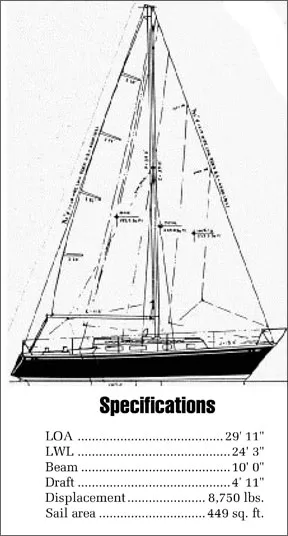

These elements combined to produce a whole generation of boats with moderate displacement, beam and draft; rudders well separated from shortened modified fin keels; and masthead rigs with a fairly high aspect ratio, none of which were particularly distorted by the dictates of a rating rule. Much about their design was traditional, yet there were significant departures: long waterlines relative to overall length, high topsides, and reverse transoms that gave them a contemporary look.

We came away with a profound realization. When you’re shopping for a 70s-vintage sailboat, it pays to find one that’s been repowered. We ran into the quintessential “barn find” when we started looking at these well-regarded boats. That gleaming red gem in the accompanying photograph is a brand-new Beta Marine diesel with 40 hours on it aboard a Tartan 30 listed for sale in Newport, RI. ($14,900…email Parker@newwaveyachts.com for more information…Parker, you owe me a beer). For comparison, we offer a photo of another used Tartan 30 listed for $12,000 showing the original Universal Atomic Four. You get the picture. When you’re boat shopping, buy the engine. If you find a previous owner who has replaced the boat’s principal machinery, it’s highly likely a sound hull and rig comes with it.

Shrouds, terminals and cordage will probably need attention, of course, and you’re probably going to find a soft spot in the deck near any penetrations. But a stout powerplant with attendant through-hulls, stuffing box, cutless bearing and prop scratches those big-ticket items off your list.

Plus, a re-power means you’ll be working with an owner who has likely taken care of business elsewhere. —Tim Cole

The result was such production boats as the Pearson 30, the Yankee 30, the Newport 30, the Cal 2-30, the Morgan 30/2, and the Scampi, to name but a few of the more familiar ones. In all, no less than two dozen boats of a similar size and type were introduced in just three years, many of them to become highly successful among sailors eager for the performance and amenities of big boats at a modest price.

Among the most noteworthy and enduring of the 30-footers from this era has been the Tartan 30. Designed by Sparkman & Stephens when that name was far and away the most prestigious in yacht design, the Tartan 30 exemplified the solidly built, comfortably appointed, fast production boat which typified not just the early 1970s, but, as it turned out, almost the whole decade (the Tartan 30 was discontinued in 1980). In her first year, 1971, the Tartan 30 was the most successful 30-footer on a wide variety of race courses; in 1976 it won the MORC of Long Island Sound, just as another had five years before.

On modern race courses the Tartan 30 gives away a lot to newer racer-cruisers with more efficient sailplans, keel configurations and use of live ballast. And, of course, they give away even more to the present breed of lighter, faster boats which are less compromised by full accommodations, interior room, and heavy rigs.

Yet these are boats whose heritage is the Tartan 30, many of which may no longer be around, let alone competitive, when the Tartan will still be winning some races.

A Close Look at the Boat

The dilemma for a designer in 1970 was to put livable accommodations in a boat with a waterline length that, a decade or so earlier, would have been a daysailer—and still have the boat perform like a racer and not a houseboat. Many of the 30-footers, indeed even larger boats, were only moderately successful with their interior layouts. The Tartan 30 is one of them. In fact, two layouts were available in the 30, one with the galley aft and the other with the galley amidships, stretched out along the starboard side. The midship galley permitted a pair of quarterberths in addition to the “convertible” cabin table/double berth available in both models. The aft galley eliminated a quarterberth but left room for a settee berth to starboard. Owners are clearly divided in their opinions of the two plans. Cooking is avowedly enhanced with the midship galley (although there is no room for a stove with oven); sleeping accommodations benefit from the settee berth arrangement.

The accommodation plan is further complicated by the placement of the engine in the forward end of the main saloon. The engine box is in the way of living space; yet, for accessibility to the engine, the location and openness are unparallelled even in boats twice the size of this one.

As with many boats of the era, the head of the 30 is cramped; so too are the V-berths in the forward cabin, the quarterberth(s), and the aft galley—all the result of the 1970 mandate by boatbuilders’ marketing honchos that as many berths a possible be crammed into all available spaces—not so the boats could sleep that many, but so the advertising could say they could.

The Tartan 30 sails well. In a breeze to windward—perhaps the best test of any boat—she is at her best: comfortable, stable, reasonably handy, and modestly dry. Off the wind she is more steerable than a host of successors with free-standing spade rudders and dagger-thin keels. Only on a broad reach with biggish following seas can her weather helm be tough to handle. Under such conditions, good sail control hardware—vang, traveler, reefing, adjustable backstay, etc—is important.

Under PHRF the Tartan 30 typically has a base rating of 170 to 180, rating faster in areas with heavier winds. In fact, in some quarters the Tartan 30 is regarded as the archetypal PHRF competitor. Her narrow inboard shroud base helps keep her competitive upwind against newer boats, and her directional stability off the wind is better. She does well against such basically similar boats with comparable ratings as the Catalina 30, the C&C 29 and 30, and, except perhaps in the lightest of air, the Pearson 30. She can stay with the likes of a J/30 (PHRF 135 or so) unless the J has a mob on her rail.

For performance in heavier winds, she needs merely a good hand on the helm and some constructive crew work. In lighter winds the Tartan 30 wants all the help she can get: a folding prop, a large, well shaped mainsail, and a genoa of at least 150%. In sailing regions with lots of really light air, her tall rig (optional at one time) is a plus.

The original engine in the 30 was the Atomic 4; by 1975 the Farymann two-cylinder diesel was an option. Located amidships, the engine turns a shaft that exits the after edge of the keel, putting the prop in perhaps its most nearly ideal location: well forward where it is protected and, offset a few degrees, efficient. In reverse, though, it is even less efficient than boats with fully exposed props on shafts.

The cockpit is of average size for boats of the Tartan 30’s vintage. Her low wood coamings are uncomfortable to either sit on or against, but the tiller is far enough aft so that there is good seating forward. The mainsheet and engine controls are awkward to handle, though. And the 30 should have a higher sill in the companionway; the original is too low to keep a flooded cockpit from emptying belowdecks.

Storage aboard the 30 is less than on many comparable boats. With either the two quarterberths or the aft galley and its cockpit-opening icebox there is little cockpit locker space. Sails are thus commonly in the way and a number of owners who sail as a couple have turned the forward berths into a sail locker. Others use the quarterberth. The area under the cockpit sole is also available but less accessible. A word of warning. The Tartan 30 is a wetter boat belowdecks than most. Not only are the quarterberths highly vulnerable to spray and rain through the companionway, but the sink is prone to filling and letting water slosh onto the sole.

What To Look For

As with so many boats as old as the 30, the potential problems fall conspicuously into two categories: cosmetic and structural. Most owners report notable degradation of the gelcoat: crazing, voids, and chalking. Blistering and deck delamination seem about average in frequency.

Belowdecks, the teak cabin sole gets the most complaints; the rather solid (if aesthetically pedestrian) plywood joinerwork gets the fewest. Like such other plain but solid boats as the Pearson 35 and C&C 35, the Tartan 30 lends itself to dressing up of the interior decor. The chainplates are prone to leaks; the ports and hull-to-deck joint seem not to be.

Any prospective owner can do his own quick check of the likeliest structural problems. Since the mast is keel-stepped, the under-deck support is not a problem. However, the mast step and mast butt should be checked, since corrosion from water leaking around the partner is common. The tabbing around the main bulkhead should also be checked

carefully. Likewise the tierod between the deck and step in the way of the mast.

The most important check is in the bilge fore and aft of the external keel. Groundings and improper hauling or storage can result in loosened floor timbers and keel bolts and flexibility or even tearing of the hull. A misaligned engine and/or a gap between deadwood and ballast are clues to such problems. Some owners, either for prevention or during repair, have reinforced the bilge area and parts of the hull where poppets bear weight during dry storage. Note: the Tartan 30 seems to be one of those boats that is

more comfortable being stored in a good cradle rather than on jackstands.

The rig, like most of those specified by Sparkman & Stephens, was designed to be practically indestructible. Given its inherent strength, look primarily for the effects of corrosion at the spreaders and the butt. Many 30s have been fitted with babystays in lieu of forward lower shrouds. For typical cruising we think the babystay is a pain and probably unnecessary, so we’d make it detachable.

Given its accessibility that should have encouraged better than average TLC, the old Atomic 4 should still be in reasonable shape. But have it mechanically checked. There have been reports of engines needing rebuilding after water backed through the exhaust. The fuel tank also tends to rust. The alternative to the Atomic 4, the Farymann diesel, is not necessarily a better bet as an engine since parts are difficult to obtain and expensive.

Conclusions

Having raced alternately on and against a well-sailed Tartan 30, we think there are few boats that have a better blend of performance, strength, and enduring styling from its era. Sure, the 30, like almost all of her contemporaries, sails, feeds, socializes, and nurtures a lot fewer crew members than she can comfortably sleep. Yet, she is a boat well suited for weekend and vacation cruising for a couple, perhaps with a child or two or an occasional guest. With a crew of four or five and a modest outlay for equipment and sails, she can be raced hard in semi-serious PHRF competition. The Tartan 30 does a lot of things of which a good 30-footer, even an old one, should be capable, while remaining a good investment.

Serendipitously, she offers rare dividends: a choice of two quite different accommodation plans, plus both an interior and an exterior that offer a superb opportunity for dressing up and customizing. The 30 is thus remarkably versatile, something that in used boats is a true—and rare—virtue.

At the risk of offending opponents of editorializing, we’d opt for the aft galley arrangement largely because we’re not big fans of quarterberths, gourmet shipboard meals, or boats that have no leeward settee berth on one tack. We would then if necessary upgrade our 30 with a good dodger, added ventilation, additional exterior wood trim, big self-tending winches (inadequate winches seem a chronic deficiency). Then, finally, for racing we’d outfit her with whatever it took to stuff it to those newer designs that think the 30 is an outdated relic.

I was the owner of that Tartan 30R that won all 6 season trophies in MORC Station #1 on Long Island Sound in 1976. Thanks for the mention. Without a doubt my Tartan 30, “Chickcharnie,” was the best of the 6 sailboats that I owned over the years. Her whole story is in my article in the June 1977 issue of Yacht Racing magazine.