Questions arise at cruising seminars and it’s always encouraging when attendees provide the answers. In one such case, a young couple asked how much a good cruising boat would cost? A more seasoned old salt, hiding in the back row responded, “all you have to spend.” His wit sparked a lengthy discussion focused on why bigger budgets almost always lead to bigger boats—it’s a topic worth exploring.

This bigger-is-better trend has accelerated in recent years. When my wife and I sailed around the world, the stereotypical cruising sailboat was a 35–40-foot sloop, cutter or ketch sailed by a two-person crew. In those days, boats tended to be older and crews were younger. Today, boats are bigger, newer, and it’s the sailors who have grown a bit older. Demographic trends show that fewer young sailors are sidelining careers and setting sail. But there’s a boom in retirees going cruising that has led to a rethink in cruising boat design along with how voyages are undertaken.

The trend is toward bigger boats, with more just-like-home accommodations. These new cruisers are equipped with power winches, bow thrusters and automated sail handling gear. Autopilots and networked navigation systems are linked to global communications equipment. And there’s often a weather router in daily contact, plus a sat phone speed dial link to the mechanic back home. Passage makers head off together and voyages are as well-scripted as a Manhattan Gala.

Builders, advertisers, and brokers have embraced the new trend and launched a ‘bigger is better’ cruising campaign. For those with the bucks to buy and maintain these boats and the skills to handle super-sized sail plans, there’s some validity to the claim. But embedded in this avalanche of enthusiasm is some very misleading spin. Of considerable concern are the ads that dub 60-65 footers with 10-foot draft, 18-foot beam and mainsails larger than 1,000 sq. ft., as “user-friendly” sailboats, easily handled by a shorthanded crew. Larger cruising boats, brimming with automation, certainly can make life aboard more convenient and comfortable. But the bottom line for those at sea remains the same: it revolves around the necessity to match sail area with the ever-changing mood of the wind and the sea. When control is lost, bad things can happen, and the following account spells out a very tragic encounter.

TRAGEDY AT SEA

Karl Volker and his wife, Annamarie Frank were ‘sailing bloggers’ who started living their dream the day they moved aboard their 67-foot CNB sloop called Escape. The boat was advertised as a luxurious home afloat—an easy-to-handle, high-performance cruiser. Three years later, the long term liveaboards had sailed Escape from Germany to the Caribbean. But on a squall-ridden night in June of 2022, while on passage from Bermuda to Nova Scotia, Karl and Annamarie encountered the unexpected. They were sailing with two additional crew, chosen from an online crew service website. Both had joined Escape in Bermuda the day before departure. It had been a typical early June weather pattern, following the weather router’s forecasts, right up until the third night out when the Gulf Stream lived up to its ill-tempered reputation.

Caught over canvased, the “all hands on deck” call came a little too late and the attempt to furl the genoa and tuck a second reef to the mainsail failed. Power winches and in-boom furling, meant to expedite the process, didn’t guarantee a favorable outcome. As the reefing effort began, the person on the helm turned the big sloop into the wind. The skipper was still reefing the jib and the person handling the mainsheet failed to trim the slack. This resulted in a viciously flogging mainsail propelling a heavy boom back and forth across the cockpit.

Annamarie stepped into the arc of the careening boom and was struck by the mainsheet and knocked to the deck unconscious. Karl rushed to her aid, and he was also hit by the flailing mainsheet with enough force to cause a compound leg fracture. The crew fought to get the vessel under control, render first aid and make contact with the US Coast Guard. The latter resulted in a daring helicopter rescue, that involved mid-route, shipboard refueling aboard a US Coast Guard Cutter. Tragically, the physical damage caused by the blunt force trauma had taken its toll. Upon reaching the cutter, Annemarie was pronounced dead, and Karl succumbed to his injuries on route to the hospital.

In the months that followed, a variety of experienced sailors weighed in on the cause of the tragedy. One of the most reoccurring themes revolved around why the crew of Escape used head-to-wind reefing. Most who commented, pointed out that turning into the wind is the last thing you want to do. It results in a flogging mainsail that can cause the boom to lash back and forth with lethal consequences, especially if there’s slack in the mainsheet. Combine this with the way a head-to-wind vessel pitches like a bucking bronco and one can see why it’s anything but the optimum angle for reefing. In the article on page 16, we take a close look at reefing alternatives and what options make most sense.

SIZE MATTERS

In the wake of this tragedy, we feel it’s time to take a close look at sailboat buying and the quest for the biggest boat you can afford. A key operating principal in the boat-buying process revolves around the assumption that vessel size needs to dovetail with crew competency. In the old days, the gentlemen of yachting had the good sense to hire a crew to handle or at least augment the boat handling aboard their classic yachts.

As the Corinthian era evolved, a sail-it-yourself ethos took shape. It was an ethos that led to smaller rather than larger vessels, that could be sailed by shorthanded crews. An interesting subset of sailors evolved. Those captains of industry who still favored larger yachts leveraged their management skills, inviting other capable yachtsmen and their athletic offspring to spend summers racing and cruising. This ensured that the big boats had enough talent to cope with the big challenges always found at sea. Names like Kialoa, Ondine, Boomerang, Running Tide and many others replaced the older professionally-crewed schooners.

DEFINING SIZE

Small, mid-size, and large cruising sailboat designations are harder to designate than hat sizes. This stems from the fact that multiple measurements play a competing role, especially when it comes to defining what fits into the mid-sized sailboat category. It takes a tape measure, weight scale and means of measuring volume to accurately answer the “small, medium, large” question. For example, a lighter, narrower beam, lower volume 35-footer can be a good candidate for the small cruiser category. While a beamy, heavier displacement, higher-volume 32-foot sailboat, such as the venerable Westsail 32, may qualify as a midsize cruiser. What both small and mid-size cruisers have in common is they are both great platforms for double handed sailing. This trait, until today, tended to separate them from larger cruising sailboats.

Another telltale factor resides in how boats of each of these groups are fitted out. For example, one has to look far and wide to find a bow thruster on a boat in the small cruiser category. But roller furling headsails have become quite ubiquitous. Diesel heat and air conditioning, once a landmark of bigger sailboats/yachts, are now a growing fancy among upper end mid-sized cruisers. Reliable hermetically sealed, low current draw compressors have made refrigeration a reality even aboard the smallest cruisers. This wide use of technology, especially networked electronics, furling systems, autopilots, and more has simplified sailing, but also carries a significant price tag. However, there’s still some interest in keeping things simple and some astounding voyages have been made in smaller, less complicated sailboats.

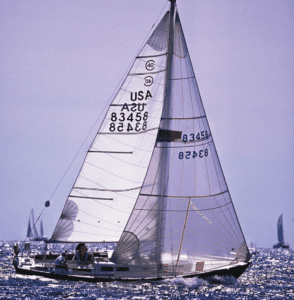

Historically, the midrange mainstream of reliable cruising boats included a good sampling of cruiser/racers and racer/cruisers that efficiently wended their way around the world. The Ericson 41 we sail is a classic example of a midsize production FRP sloop that was up to the task. One of the first dedicated cruisers was the Valiant 40 a Robert Perry design that collectively accrued more sea miles than most other production cruisers. Part of the reason for the boat’s popularity was its combination of ability under sail and usable liveaboard interior. Eventually, pressure for a commodious aft cabin and more amenities bumped out the beam and increased the displacement of many midsize cruisers. Today’s midsize passage makers have more sail area, more auxiliary horsepower and cost five times as much as a Cal 40 that won more than its fair share of ocean races and has cruised far and wide.

THE 60-PLUS CLUB

There’s been a growing interest in shorthanded cruising aboard larger and larger sailboats—a trend that’s both encouraging and worrisome. Part of the problem stems from the accomplishments of singlehanders aboard 60 foot plus sailboats surfing the two story high Southern Ocean swells. These pro athletes have skills, fitness levels and seamanship awareness that go far beyond that of the average sailor. But when seen from a distance, their agility and sail handling skills make fast passages look all too easy.

There’s also a financial hurdle that’s limited entry into the big league of super-sized cruising. Larger sailboats have long been the domain of one-off designers and custom builders. It’s been a niche industry that has created a legacy of fine yachts. However, the abiding principal has been large sailboats require larger crews and pros should be hired when necessary.

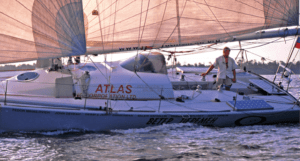

Voyagers like Steve and Linda Dashew have changed the paradigm. They are strong advocates of shorthanded big boat cruising and make it clear what talents are needed. They advocate weather awareness and the importance of keeping all systems in good working order. The Dashew’s pioneered a line of big cruising boats to be sailed by shorthanded crews. The Sundeer and Deerfoot lineup featured utilitarian exteriors, functional sail handling systems and sumptuous interiors. Their goal was to deliver a sixty-foot plus long-term liveaboard that was ready cross oceans efficiently.

THE SMALL-BOAT CROWD

Tim and Pauline Carr took the other tack. They were strong advocates of keeping the boat small and the systems simple. They sailed their 28-foot Falmouth Quay Punt, Curlew, built in 1898, all over the world, including a junket down to Antarctica. They did so with neither engine nor electronics, but this doesn’t mean that a small, old wooden sloop is best the bet for every cruiser.

Dave and Jaja Martin, also small boat adventurers, opted for a fiberglass boat four-feet shorter than Curlew. Dave became a gifted shipwright through a learn-by-doing apprenticeship. When he was in his early twenties, he took over the Cal 25 that and his dad had double-handed from Seattle to the Caribbean.

Lenore and I met Dave while cruising in the Bahamas and were captivated by his tenacity and plans for adventure. He took me up on an offer to sail up to Long Island Sound to work in a boatyard I was running. It was a job that would also give him a chance to refit his tired Cal 25 and outfit for further adventure.

It’s not easy to turn a fantasy into reality, especially when it involves a tight budget and a tired little boat. But Dave defied the odds. His 40/40 plan was to work for the boatyard 40 hours a week and work on his own boat 40 hours a week. He lived in the loft above the carpentry shop and held to his plan. During his two years in residence, he de-rigged and dismantled the boat, reinforced the hull and deck, laminated floor frames and stringers, rebuilt the rudder and rerigged the mast—renaming her Direction.

The second spring arrived, and we were launching clients 30, 40 and 50 footers, gleaming with fresh varnish and all shades of LPU paint. Most were tethered to moorings just as their predecessors had been for more than a century. Finally, a highly modified Cal 25 took to the water, dwarfed by the size and prestige of the surrounding fleet. As opening day revelry brought the season to life, one of the smallest boats in the bay, almost invisible to onlookers, set sail on a voyage that would circle the globe.

Dave Martin had gotten only one thing terribly wrong—single handing was not his preferred routine. In the Caribbean, he had met a kindred spirit with a familiar sense of adventure, and the shipmates were soon to be a married couple. In New Zealand they had their first child, a second in Australia, and with four aboard, Jaja and Dave sailed Direction westward. The Martins eventually rounded the Cape of Good Hope, welcoming the trade wind reach across the Atlantic and a return to the US to rebuild a 32- foot-steel sloop and set off on a family cruise of the Atlantic’s high latitudes and the Arctic.

Today, the Martins live ashore in Maine where Dave and Jaja built a house and a Wharram catamaran for local cruising. Their daughter, Holly Martin has singlehanded her 27-foot sloop Gecko from Maine to French Polynesia, carrying on a family tradition.

Small cruising boats can still deliver big rewards, their upside includes easy handling, less time consumed with maintenance and lower costs. Yes, there are do-without factors but as one backpacker/mountaineering friend said, “that 20-something footer seems the lap of luxury to me!”

Mid-sized cruising boats, remain a mainstay of the sailboat market. Over the last several decades, these vessels have significantly increased their interior volume. The average length has remained in the 35-45 foot range, but hull shapes have changed to enhance aft cabin accommodations. In many cases this beamier hull shape has been merged with a shoal draft keel. However when such a design heels, the wide beam causes the keel’s lateral plane’s lift to greatly diminish and hinder windward performance.

Those intent on sailing long passages should consider performance under sail as well as accommodations below and recognize the tradeoffs. Deeper draft improves windward performance, and a displacement/ballast ratio of 120 degrees or greater will insure a rapid recovery from a knockdown.

CONCLUSION

In the midst of writing this article, my attention was drawn to a front-page sailing story in the mainstream press. It was another disaster at sea account, but fortunately, this time it had a happy ending. A two-person crew, along with a miniature poodle, had set sail from Oregon Inlet, NC aboard a Catalina 30. It was Dec 3, 2022 and the crew’s planned passage to Florida kicked off with the rounding of Cape Hatteras, prime time for bad weather during winter. The vessel was dismasted, ran out of fuel and lay a hull for ten days as two severe cold fronts and deep low pressure systems tormented the little sloop. Finally, a tanker spotted them 214 miles off the Delaware coastline and rescued the crew and their poodle.

Yes, there’s a host of safety questions pertaining to time of year, equipage, and lack of communications gear, but one thing is quite evident. The crew of the Catalina 30 were in violent wintertime conditions, lost their rig, but the little sloop remained afloat and the crew survived. It was a different story in June aboard the 67-foot sloop Escape, a much larger and theoretically safer vessel. In that instance the owners perished attempting to regain control of the mainsail. In both cases, missteps and weather volatility turned their passage into a survival encounter.

Navigation and Marine Weather Instructor at the Annapolis School of Seamanship and PS contributing editor Ralph Naranjo is the author of The Art of Seamanship: Evolving Skills, Exploring Oceans, and Handling Wind, Waves and Weather.

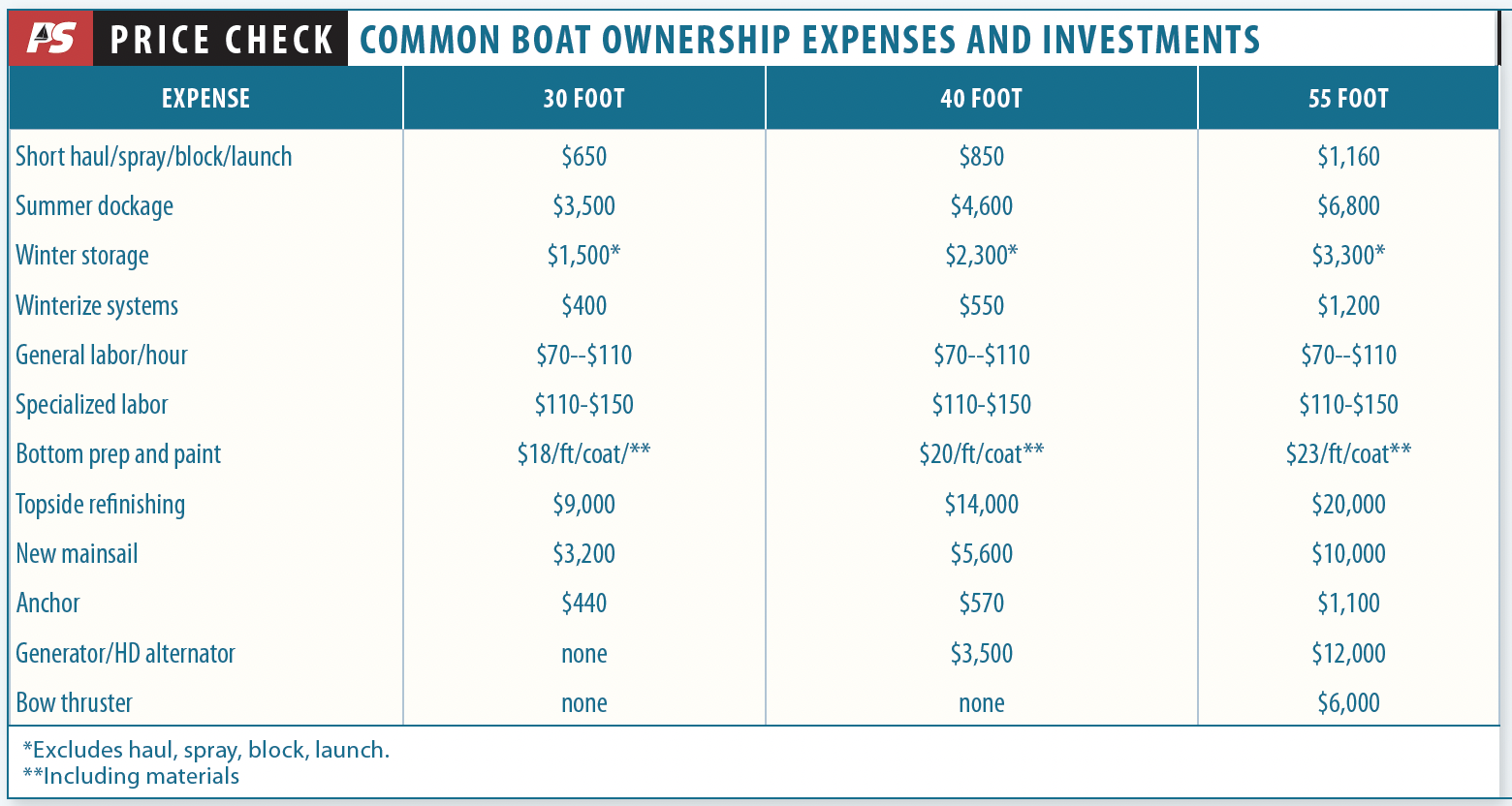

The old salt’s advice that “a good cruising boat will cost you all you have to spend,” is actually a bit misleading, because there will be plenty of ongoing expenses that need to be covered. Some of these reoccur like clockwork, others are far less predictable. In both cases, contingency funds are an important part of any boat budget.

As one might expect, smaller, less complicated sailboats are less costly to maintain than larger boats with more complicated systems. In some cases, expenses are linear. Good examples are slip fees, haul-store-launch charges, and bottom painting invoices. But when it comes to more complex projects, terms like “time and materials” and “it looks like a labor intensive job” take on special meaning to every boat owner. Experienced skippers seek quotes on major work and experienced boatyard managers understand that the full extent of certain repairs can’t be fully discerned until considerable disassembly is carried out. This means that a lot rides on boatyard–boat owner communication and trust.

The do-it-yourself shortcut is a feasible alternative for those with the skill, time, and inclination to tackle boat projects themselves. Those seeking a painless shortcut in lieu of paying hefty boatyard bills should beware of what projects they undertake. Spending inordinate amounts of time making something more broken is never a good tack. And it often ends up being more costly in the long run. That said, those skilled with hand tools, in possession of the right manuals and having previously tackled similar jobs are usually capable to doing much of their own boat’s maintenance, especially aboard a smaller sailboat with less complex systems.

The attached table profiles a sampling of some of the more common sailboat expenses. It reveals how bigger boats create larger holes in the water in which one’s finances can rapidly disappear. One thing that is missing, however, is the net effect of rapidly rising labor rates. Take for example the way the great surge in technology is encouraging sailors to climate control cabins and make their boats more complex and energy consuming than ever. A case in point involves the new owners of a nine-year-old 47 foot multihull who’s equipment adding appetite overwhelmed the factory installed electrical system.

When all was said and done, the failed original DC electrical system was replaced with all-new components and a rewired, charging and electrical distribution system. Current was stored in an extra heavy-duty bank of Lithium batteries required to run an array of amenities.

The price for the refit and upgrade approached $70,000. Cruise plans had to be delayed and the question that lingers is how much shoreside lifestyle does a sailboat really need? There are many answers to that query, but for those who seek a less complex solution, consider the slogan of small-boat sailing icons Lynn and Larry Pardey, authors of “The Self-sufficent Cruiser,” who urge sailors to “Go small, go now.”

The consensus among experienced offshore sailors is that the preferred point of sail for reefing a boom-furling mainsail is a reach. This entails bearing away onto a close or beam reach, easing the traveler, and adjusting the mainsheet to depower the mainsail so it’s spilling breeze but not flogging. How close or deep a reach depends on the sweep-back angle of the spreaders, sea state, and the furling system itself. It’s essential to hold a steady course and keep just enough tension on the main sheet to maintain a mostly depowered mainsail. Next, ease the halyard and rotate the in-boom furling mandrel in unison, insuring an even and compact furl.

Prior to reefing, make sure that the boom-to-mast angle meets manufacturer’s recommendations, usually around 87 degrees. Also, overtrim the headsail so it will deliver less drive and more roll dampening effect. During the reef, continue ensure that the halyard release rate keeps pace with the rate of the mandrel rotation. Note how the sail luff is layering, and if necessary, slightly change the boom angle to keep the luff from crowding the gooseneck or moving too far aft. This approach to reefing lessens the apparent wind and dampens the vessel’s pitch and roll. It also moves the boom and main sheet tackle away from the center of the cockpit.

As mentioned above, it’s time to abandon the idea that reefing the mainsail requires a turn into the wind. Doing so eliminates the stability derived from a trimmed headsail and a depowered but non-flogging mainsail.

Turning head-to-wind causes the vessel to increase its pitch and roll, while at the same time making mainsail control much more difficult. This isn’t just the idle opinion of a few old salts, it’s the dogma spelled out in the manuals written by the experts at Forespar’s Liesurefurl, GMT, Schaefer and other boom furling manufacturers.

The big debate revolves around how deep a reach provides the best angle of attack for in-boom furler reefing, or for that matter all reefing. Those who favor a broad reach like the way it eliminates pounding into a seaway. However, it also requires more mainsheet easing and a wider boom angle. And as the halyard is eased and the leech falls off, there’s more chance that the sail will press against the spreaders, especially if they are swept back, as in a backstayless B&R rig common on Hunter models.

An attentive person on the helm plays a vital role during the deep-reach reefing process. As the boat accelerates down wave faces, the apparent wind comes forward if the helmsperson bares away they must be ready for the apparent wind to go even further aft as boat speed decreases. To deep a reach raises the specter of a jibe during reefing which will add an addition layer of woe. Those who reef on a close or beam reach seem to have the right compromise.

Good steering compensates for these shifts and is part the reefing process, as is the dexterity a helmsperson displays in avoiding a wave induced jibe.

RELIEVING BACKWINDED MAIN

A preventer can eliminate the hazard linked to the boom crossing the deck during an accidental jibe. But it can also leave a crew, engaged in the middle of a mainsail reefing effort, caught in a tricky back-winded fire drill. In essence, a jibe with a preventer set puts a sailboat into a pinned down position with the backwinded jib and mainsail held to windward by the preventer. This is when the crew realizes that the preventer now handles as much load as the mainsheet did a few minutes ago, and it’s doing so at a 1-to-1 ratio rather than the usual 4-to-1 reduction that a mainsheet creates. It’s also when the crew fully appreciates having secured the preventer to as large a winch as possible (see “The Best Prevention is a Preventer,” see PS July 2017.

A preventer can keep an unintentional jibe from becoming a lethal threat to the crew, but only if it includes an effective means of handling a backwinded mainsail and a boat pinned over on its rail. In such circumstances, the best preventer option is one that has been led from the boom end to a block at the bow and returned to a big winch in the cockpit. This single part line now holds the same force once handled by a multipart mainsheet. By securing the preventer tail to a large cockpit winch, the preventer can be safely eased and the vessel brought back under control.

Other options, such as attaching a mid-boom, cam cleat equipped, block and tackle to the rail may work to keep the boom from careening across the deck. But the real challenge is easing the back winded mainsail and getting the boat back on its feet.

There’s a love-hate relationship apparent when talk turns to topping lifts. Advocates love the aid they offer when reefing a mainsail. Slab reefing is expedited by over tensioning the “topper”, tipping up the boom end and making it much easier to set the new leech cringle. Boom furling systems gain a welcome means of boom angle tweaking when a topping lift is part of the running rigging.

Opponents hate the flailing line as it endlessly assails the leech of the mainsail. On long voyages the line can chafe seam stitching and damage the sailcloth. The greater the mainsail’s roach, the more problematic this issue becomes. Some rig a snap shackle to the topping lift that allows it to be quickly removed and clipped to a pennant attached to the stern rail, ready to attach when needed. In such cases, a mechanical or hydraulic vang/boom support is also used to keep the outboard boom end from dropping into the cockpit if the halyard breaks or is inadvertently released. Traditionally a boom gallows added this rollbar-like protection.

Another valuable reefing tactic of value to shorthanded crews is utilizing a heave-to position to tuck in a reef. The opposing back winded headsail and rudder turned in opposition leaves the vessel sedately crabbing sideways with a slow forereaching motion. The mainsail sheet is eased to the point of spilling breeze but not flogging and reefing is easy to accomplish. Once all is tucked and tightened, release the backwinded headsail and you’re back underway.

in the example in the article where the smaller boat was de-masted in bad weather, and the sailors and their dog survived until they were spotted and rescued, is there an implication that if a larger boat were de-masted and in the same unfortunate predicament, that the size of the larger boat would be problematic vs the smaller hull? As a newbe and potential passage maker any thoughts would be appreciated.

I have a “wrinkle” in the top end of my roller-furling mainstay. I believe it was caused by not having the furler tight to the top of its run. It snagged up on me while trying to furl for the approaching Nicole last fall. I eventually had to cut away my old genoa which was flogging around like a wild stallion. After taking down the mast for winter boat storage, I noticed the damage to the stay. I will have to replace it this spring. Any advice? P.S. My boat is an extensively renovated Hunter 27 and the roller furler is a Pro-furl.