The Catalina 250 is one of a group of relatively lightweight, shallow-draft trailerable cruising boats that appeared in the mid-1990s, utilizing water ballast to provide stability. These boats—notably the C-250, the Hunter 26, and the MacGregor 26—all are of very modern design, are relatively inexpensive, and feature workmanship and materials of generally serviceable but by no means superior quality. Their sailing qualities and accommodation plans make them suitable for daysailing and casual overnighting, rather than for serious cruising.

Such boats tend to attract mainly first-time buyers, the budget-conscious, and those who give a high priority to the mobility and self-storage that goes with trailerability. We believe that most experienced sailors—generally folks who like to go cruising for more than a few days at a time, occasionally find themselves offshore in unpredictable weather, and prefer a boat that looks like a boat in the traditional sense—will find that the new crop of water ballasted boats are not suited to their needs.

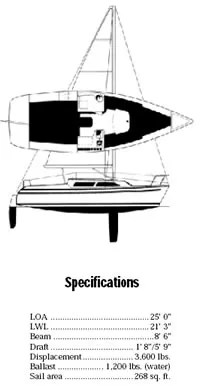

Design

At first glance, utilizing water ballast would seem to be ideal for trailering. Afloat, the weight of the water (in theory at least) provides stiffness under sail. And when it’s time to hitch up the trailer, the ballast water is drained, lightening the hull and thus making it easier to tow.

However, there are problems: (1) the depth of the ballast, which cannot be very low if the shallow draft so desirable for launching a boat from a ramp is to be maintained; (2) the need to spread it out into the ends of the hull in order to attain enough weight to be effective; and (3) its density, which by necessity is the same as the medium in which it is immersed— less than 1/11th the density of lead, the most popular ballast material. Without getting into a complicated discussion of metacentric heights and centers of buoyancy versus centers of gravity, suffice it to say that the deeper the ballast the stiffer the hull, the heavier the ballast the stiffer the hull, and the lighter the ends of its hull the faster the boat. These are the facts of life, and so far no one, including Catalina, has come up with a way to get around them.

The C-250’s ballast tank is basically a slab-like box inside the bottom of the hull. It measures an average of only about 6″ high, and is shaped in plan view something like a smaller version of the waterline of the boat, extending close to 14′ from the stem to just aft of the companionway ladder along the keel, and outward to the hull skin along the sides. This provides a compartment of a little less than 19 cubic feet, containing 1,200 pounds of water. That may sound like a lot, until you consider that the same volume of lead would weigh 13,284 pounds, and the ballast is concentrated less than 18″ below the waterline with the boat floating level. The result is that the boat is not as stiff under sail as its lead-ballasted keelcenterboard cousins, such as the Precision 23.

Looking beyond the technical aspects of design, we see a boat that does not match our traditional ideas as to how a sailboat should look. However, this is a subjective matter, so we leave it to the reader to decide what looks good and what doesn’t.

Performance and Handling

The C-250’s cockpit-mounted outboard, full-battened main, and relatively small (110%) jib all contribute to relatively easy handling. In fact, the owner of our test boat frequently singlehands. However, he discovered it’s a nuisance to tack by himself, since the jib sheet winches are nowhere near the tiller. To tack, he has to abandon the tiller, move to the forward end of the cockpit, uncleat the lazy sheet, pull it off the winch, then move back to the helm before the boat strays too far. When it has passed through the eye of the wind, he again leaves the helm, grabs the new sheet, gives it a couple of turns around the new sheet winch, then trims. This activity isn’t helped by the fact that (A) neither winch handle can be cranked through 360 degrees without crushing your knuckles against the nearby lifeline stanchion (which is less than 9″ away from the winch centerline), (B) the jib sheet lead runs from its winch to a Harken cam cleat, mounted very close to the winch drum, and (C) the lead from the cleat runs across the boat, rather than aft. We’d rather see the winches moved a foot or so forward on the cabintop, and the direction of hauling switched to straight aft, so a singlehander can trim from farther back in the cockpit. A longer tiller or a telescoping tiller extension could help alleviate the problem.

The C-250 has a relatively easy motion, characteristic of a more heavily ballasted boat, no doubt due to the spread-out water ballast. As another boating writer pointed out, the C-250 “doesn’t bob and pitch like a lightweight.” One tends to think of this characteristic a big plus, until one remembers that the slower rhythm of the pitching is at least partly the result of the boat’s spread-out water ballast, making its heavy ends act like twin pendulums, thereby cutting its speed through waves. Where boat speed is concerned, it’s well to remember that “bobbing and pitching” isn’t all bad.

Under power, our test boat was easily controlled, and made close to 6 knots in flat water with the engine wide open. The owner’s Honda 8-hp. Outboard was about the right size, though a 6-hp. Unit might have done as well, assuming no more than three or four passengers and a normal payload. A long shaft engine is required, and an extra long shaft (XLS) is recommended by the manufacturer.

We sailed the test boat in a light breeze of 4 to 8 knots, with puffs to 10, and virtually no chop. With three aboard, all sitting to leeward to test stability, we got the boat to heel to 20° in about 7 knots of breeze, close hauled. With the same crew complement redeployed to weather, we figure the boat could stand up to winds of 12 knots or so without heeling more. Above that angle, even considering that the stock 110% jib is relatively small, it probably would be time to reef the main.

We didn’t attempt to reef the main, but we could see that it would be a bit difficult, given the way the controls are rigged. The single reefing line leads from a bail on the boom, up to the leech cringle, then down to the boom again and forward, then up to the luff reefing cringle, then down toward the deck. But rather than the conventional lead, descending all the way to the deck, reversing direction through a deck block, then rising to a cleat on the mast, on the C-250 the lead is directly from the reef cringle down to the cleat. Adding the extra block on deck would allow easier handling, thereby improving the reefing system significantly, at little additional expense.

Actually, reefing the main at sea would be virtually impossible, given the way the test boat was delivered, with no topping lift on the main boom. The owner added it later.

Sails that come with the boat are “Catalina” brand, constructed of soft-lay Dacron, and we judged them to be serviceable but not high-performance quality. Our test boat pointed within 45° of the wind, and on a reach, sailed at about 5 knots in the puffs. We figured the boat could probably add a half knot on at least some points of sail if it was given a suit of sails with a bit flatter shape and less curl at the leech. We’d also like to see sacrificial UV edge panels on the roller-furling jib, rather than UV-treated Dacron as supplied. Without them, a separate sock (not supplied by Catalina) is required to ward off accelerated deterioration of sailcloth due to the sun’s ultraviolet rays.

Downwind performance would also be improved if the acutely swept-back shrouds (chainplates 24″ abaft the mast) were repositioned, so the boom could swing farther forward.

Our test boat was equipped with a tiller rather than the optional Edson wheel. We recommend against a wheel for this size and type of boat, for many reasons: It’s easier with a tiller to feel when the boat is balanced under sail; it’s faster to turn with a tiller; and a tiller is over a thousand dollars less expensive.

Steering on the C-250 was relatively light and balanced, though directional stability was not great, probably a result of the fin-like centerboard and tall, narrow rudder. Thus, even with the sails trimmed perfectly, we found we couldn’t let go of the helm for more than a few seconds before it began to wander up into the wind in the puffs, or bear off in the lulls.

Nevertheless, we were surprised at its relatively good balance, considering the sailplan, underwater profile, and lead. The lead, of course, is the horizontal distance between the sails’ center of effort (CE) brought down to the waterline, and the center of the underwater profile (excluding the area of the rudder), or center of lateral plane (CLP), brought up to the waterline. The rule-of-thumb for the lead of a well-balanced sloop is usually about 14% to 19% of the designed waterline length, with the CE always forward of the CLP. For the C-250, the CE is only about 6″ aft of the mast; by the above rule-of-thumb, the CLP should be about 3′ to 4′ feet aft of the mast. The profile drawing on the brochure indicates that the center of area of the full-down centerboard (virtually at the same location as the CLP) is practically in line with the mast—way too far forward. Normally this would mean a very hard-mouthed helm, with the boat constantly trying to head up into the wind—yet that didn’t happen in the light wind in which we sailed. We were sorry the wind didn’t pipe up more during our test, which would show for sure whether or not the C-250’s design was a rare exception to the lead rule.

In discussing this situation with Gerry Douglas, Catalina’s vice president and chief designer, we learned that the sail plan/profile in the latest sales brochure (dated January, 1995) is incorrectly drawn, in that the board’s full-down position is swept back about 15°, rather than being vertical as shown. But even then, the CLP is nowhere near 3′ to 4′ feet aft of the mast.

With the four-part vang (included as standard equipment), we didn’t miss the absence of a traveler, since we were able to employ vangsheeting. Garhauer supplies most of the deck gear for the C-250, including the vang, blocks and chainplates. Hardware quality seemed uniformly serviceable, though not fancy. Cabintop jib winches are little Lewmar #6s, okay for the 110% jib but not for a larger headsail.

We found it quite awkward to move back and forth between the cockpit and the forward deck, especially with the boat heeled and the main hatch open. The smoked Plexiglas main hatch, if closed, might have made it easier to move around, but the boat’s owner was concerned that it might get scratched. An extra set of stanchions midway between the existing ones would help.

The C-250 sales literature lists “halyards led aft to the cockpit” as a standard feature. This is not accomplished in the conventional manner—turning blocks at the mast base, and rope clutches at the aft end of the cabintop. Instead, the turning blocks are combined with cam cleats right at the mast, and the halyards are cleated at long distance. This simplifies rigging and derigging at a launching ramp, but caused a problem on our test boat: The projecting blocks and cleats can foul a flailing jib sheet during a tack. Also, with sails flying, there is no obvious out-of-the-way place to store the lengthy halyards. Consequently, we’d prefer the more conventional arrangement despite the slightly greater effort required to rig and unrig.

Construction

The deck is cored with plywood for stiffness, and the cabintop is cored with end-grain balsa to minimize weight high up. The hull is a solid laminate, using knitted fiberglass fabric and a vinylester skin. Catalina says the boat has a “blister-resistant gel coat” and the company offers a limited 5-year gelcoat warranty.

The C-250’s hull-deck joint is a modified shoe box type, with a vertical deck flange fitted over the turned-out rim of the hull, creating a joint with both vertical and horizontal mating surfaces—a strong configuration. Before fitting, all surfaces of the joint are swabbed with glue (in this case a bonding putty made with filled polyester resin), and are held together with pop rivets on roughly 3″ centers while the glue hardens. The rivets are left in place, but probably contribute little if any mechanical support to the joint. A C-shaped rubrail covers the line of pop rivets. The arrangement is neat and strong, but the effect from the exterior is not very salty.

The interior hull liner is very extensive, dressing up the cabin nicely, but at the same time almost totally thwarting any efforts to access the inside of the outer skin to make repairs or run electric wires. Still, there is a 1/4″ to 1/2″ space between the liner and hull, if you can find a way to get to it. It is joined to the hull along the sheer flange, and is tabbed at seatbacks and seat risers.

The early Catalina brochures announced that the C-250 had positive flotation, meaning the boat would float when holed. But before production started, the designers decided that flotation space would carve too much living space out of the cabin. So in the production version, there’s no special flotation.

The rudder is of composite construction, with a fiberglass skin covering a rigid foam core. Its crosssection appears to be an efficient foil shape with asquare trailing edge about 3/16″ wide (considered good design). Strangely, the standard rudder is fixed rather than a kick-up type. Because the rudder is by far the deepest part of the boat, and therefore vulnerable to damage, we’d purchase the optional kick-up rudder (we think it should be standard). Otherwise, as one owner noted: “The specified 1′ 8” draft with the board up is with the rudder off, [making] the boat unsteerable!”

The foil-shaped, fiberglass centerboard has a 3/ 16″ thick stainless steel reinforcing structure and some lead in the lower section. The board weighs about 90 pounds.

On Deck

The cockpit is designed for comfort, with fairly high coamings and seat dimensions to suit most people. However, the cockpit seats are 17″ wide, great for sitting but not for sleeping under the stars. Sleeping on the cockpit floor is a possibility, since it’s 26″ wide—but you’d better be short, as it’s length in the clear is only 68″. Visibility from the helm is good.

We liked the convenient location of the outboard motor controls, with the motor head accessible without having to reach over the stern. We also liked the fact that a manual bilge pump, located in the port footwell wall, comes standard; and that the cabin table can be set up in the cockpit for al fresco dining.

The cockpit seemed reasonably safe to us, despite the open transom. Any water that washed in over the sole (not protected from big following seas by even as much as a toerail) would be stopped from entering the cabin by a full bridge deck forward, and would drain out quickly via the same opening. Warning: Be careful not to drop anything that rolls onto the cockpit sole, and if the wash from a passing powerboat comes at you from astern, lift your feet quickly off the sole!

Stowage in the cockpit, in small (10″ x 12″ x 30″) under-seat lockers, is sparse. So is the so-called “fuel locker” (the molded fiberglass box just forward of the rudder) which, according to the owner’s manual, is supposed to hold a 6-gallon fuel tank. We don’t see how; in the test boat, at least, the opening in the top of the 13″ deep box is only 12-1/4″ x 18-5/8″ with two of the four corners cut off by trim. A 6-gallon Tempo plastic tank measures 22″ x 14″; even a standard portable metal Yamaha tank has a footprint measuring 12-1/2″ x 18-1/2″, and won’t fit. We tried. The owner of our test boat uses a plastic 3-gallon tank from Honda, which does fit.

The anchor locker at the bow, a triangular compartment with a fiberglass hinged lid, is a little too small. The owner’s manual states it is big enough for a 13-pound anchor. However, when we tried to insert a 13-pound U.S. Anchor (a Danforth type), it wasn’t wide enough for the 21″ stock; the premolded notch in the locker is only 18″ wide.

Some anchors rated at 13 pounds will fit. For example, the test boat’s owner happened to have a small (FX-7) Fortress aluminum anchor which fit perfectly. And there is 7″ of space below the anchor, enough for at least a hundred feet of neatly coiled 3/ 8″ line. Be sure to check the dimensions before buying an anchor.

Interior

The layout below is similar to many other modern sailboats under 30′: A single bright and airy cabin; Vberth forward, extending aft to twin settees forming a U-shaped dining area around a table supported by the mast compression post; an enclosed head compartment complete with a solid teak plywood door; small galley; and a big aft berth behind the companionway ladder, under the cockpit.

In our opinion, Catalina does a workmanlike job of decorating interiors on a tight budget, and the C- 250 is no exception. We liked the minimal use of teak—just enough to keep the cabin from looking like the proverbial bathtub. We also liked the hull lining from berth-top to sheer clamp, a molded white plastic “ceiling” meant to look like painted wood strips, but much easier to maintain. A teak trim strip, meant to look like a sheer clamp, helps to break up the allwhite plastic upper half of the cabin.

Unfortunately, cabin headroom is only 4′ 6″, both at the galley and in the head. That’s considerably less than the C-250’s arch competitor, the water-ballasted Hunter 26.

Catalina claims the main hatch on the C-250 is a “pop-top,” but in our opinion, this hatch is not a “pop-top” in the usual sense. We think that, by definition, a true pop-top hatch can be moved upward by rods at all four corners, resulting in a raised roof which is horizontal, or nearly so. Such a pop-top does not materially affect visibility from the helm if canvas side-curtains are not erected, nor does it usually interfere with operation of the mainsail or boom, and therefore in most situations may be used underway. In contrast, the Catalina hatch is hinged at its forward end, and when the aft end is raised, slightly improving headroom aft, forward visibility is reduced too much to safely attempt navigation.

Ventilation is adequate except for the hottest days. The forward hatch is solid fiberglass (no translucent top), and measures 18-1/2″ x 20″. When closed, it is sealed by a polyurethane foam weather strip— probably effective, but not elegant. The sliding main hatch, a slab of 3/8″ smoked acrylic, is big—38″ x 33″. It slides into the hinged, so-called pop-top.

The fixed portlight in the head has a 4″ x 10″ opening-port insert, which adds only minimal ventilation. An overhead hatch, cowl or Dorade vent would be better.

Light, like ventilation, is adequate for most conditions. During the day, there is plenty of natural light even without a translucent forward hatch. At night, a battery, recharged by the alternator presumed to come with whatever outboard engine the owner decides to buy, supplies the lighting system. Besides a complete set of running lights, steaming light, and anchor light, the battery powers four 5″ dome lights and two small spots over the dining table. It’s enough light for eating, but if you like to read in bed, you’ll need to add lighting.

We liked the cloth upholstery on the settees and forward V-berth—a blue suede-like material. Oddly, the aft berth cushion on our test boat was different, a light colored contemporary cotton print. The 3″ cushions were comfortable, but a heavy person might disagree.

The V-berth measures 75″ long, 68″ across the wide end, and 10″ across the narrow (bow) end—enough space for a very friendly medium-sized couple. The big berth aft has more horizontal space for two, being 76″ front-to-back, 72″ across the forward end and 56″ across the end nearest the transom. For most of its width, however, the overhead is only 17″ above the cushion top.

In early models, the dining table could be lowered to form an extension to the forward sleeping area, transforming it into a “giant berth.” Though it seem to us like a sound idea, this arrangement has been discontinued.

The removable cabin table is 37″ x 34″, with rounded corners to prevent hip and thigh bruises. It is 3/4″ thick, with a durable melamine surface, and is well braced by the 2-1/4″ anodized aluminum compression post, as well as by a pair of folding legs.

When the forward “giant berth” extension was discontinued, a permanently fixed small cocktail table, 14″ x 25″ with a teak veneer surface, was added under the removable table. It’s occasionally handy when the big table is not in place, but is too small and low for most purposes.

The galley is small, meant for weekending. Consequently, equipment is minimal: The stove is a single burner Princess gas model, fed through a hose from a butane canister (ABYC allows just one 8-oz. canister below deck at a time).

There are a few cabinet doors and drawers, but nothing like most sailors would want on a long cruise. Aft of the sink and stove is a space under the galley counter for a large (48-quart) portable Coleman ice chest, suitable for no more than short cruises. And the water tank under the sink contains a minuscule 5 gallons.

Neither the galley sink nor the head sink uses a through-hull on the drain. Yes, we realize the throughhull fittings (white plastic stubs) are located approximately 7″ above the waterline when the boat is floating level. And yes, we know how expensive seacocks are. We still think they should be fitted to avoid seawater backing up when the boat is heeled. Plus, plastic tends to degrade in UV.

The 5-gallon plastic water jug under the galley sink is very difficult to remove for filling or cleaning, due to the maze of hoses and other paraphernalia. Consequently, it’s best filled in situ with a garden hose, which we judge to be somewhat of a nuisance.

The 12-volt battery, according to the owner’s manual, is a 90-amp-hour, marine-grade, deep-cycle model. We found it next to impossible to check due to its awkward position in line with the keel and far aft, behind a hatch in the bulkhead at the aft end of the under-cockpit berth. It sits inside a plastic case in a molded fiberglass tray, strapped in place with only a few inches of space between it and the deck. There is not enough space to add a second battery without destroying the built-in tray and relocating it.

The head compartment contains a portable toilet (a nuisance compared to a permanent head, in our opinion), a tiny sink with cabinet under, and a small hanging locker, handy for stowing wet foul weather gear.

Trailer

The owner of our test boat, who likes shallow-water cruising, was attracted not by the mobility of a trailerable boat, but instead by its very shoal (20″) draft. He purchased his C-250 without a trailer, so we didn’t get to check out either the trailer or the ease of rigging, launching, retrieving, and unrigging.

For the record, a properly equipped trailer costs about $2,500 to $2,700, including galvanizing, surge brakes, winch, trailer ladder, and car-sized wheels. Brand name and features depend to some extent on which dealer you use.

In any case, the relatively easy trailerability of the C-250 cannot be denied. The boat, empty and dry, with the spars tied down on deck, weighs 2,400 pounds. Add to that the weight of a trailer (about 1,300 pounds), outboard motor and fuel, water ballast not drained, personal gear and supplies, etc., and you have, probably, another 2,000 pounds, bringing the total to about 4,400 pounds at the towbar. That weight puts the C-250 in the capacity range of a large cars, sports-utility vehicles, and vans, including, for example, the Buick Roadmaster wagon, Chevy Caprice,

Ford Crown Victoria, Olds Custom Cruiser, Ford Aerostar, and Mazda MPV, when properly equipped with a trailer-towing package.

However, one of the biggest strains on a tow vehicle is when it’s pulling a boat and trailer up a steep ramp during haul-out. Unfortunately, with a gravity-drain of the water ballast, such as on the C- 250, not all of the 144 gallons will have been drained on the ramp, since it takes 7 minutes to empty the tank with the boat level and on dry land—more time when the boat starts out at an angle and the tank outlet is still submerged. On crowded launching ramps with strict time limits or too many impatient boaters waiting in line, owners may have to pull the boat out with virtually all 1,200 pounds of ballast water still aboard. In that case, the tow vehicle would be pulling—up hill, possibly on wet, slick pavement— a load of not 4,400, but 5,600 pounds. Few of the vehicles mentioned above are rated to do that. So, before buying, give careful consideration to your intended tow vehicle. These considerations are not just peculiar to the Catalina 250.

Summary

The C-250 is a purpose-built boat, adequate for daysailing or overnighting. It comes with a passel of standard features, not the least of which is a 5-year hull structure and gelcoat blister warranty. (Early hulls did have some serious hull problems, including a leak that influenced Catalina’s decision to completely redesign the water ballast tank mold. But Catalina tells us the early hulls have all been retrofitted or are in the process of being corrected.)

Also included as standard are sails, mast carrier, pivoting mast step, boom vang, jiffy reefing gear (except for one key block), a three-step swim ladder hinged on the transom, pulpit, lifelines and stanchions, trailer bow eye, and other extras.

Catalina doesn’t publish an official list base price, and we couldn’t get an exact quote from the dealers we talked to, but by doing a few calculations, we estimated that the base price FOB factory (Woodland Hills, California) when we tested the boat in 1996 was about $15,800. If you’re on the East Coast, freight could add close to $2,000. Then there’s commissioning,which may be a nominal $100 to $200, or may escalate for bottom painting, electronics installation, and so on.

Fully equipped with trailer, engine, optional canvas, full electronics, and other goodies, we could expect to pay close to $25,000. This seems fair to us, even when compared to $12,000 for the MacGregor complete with trailer. The Catalina is just more boat. However, the sailaway prices we saw from two different dealers on the East Coast included an extra $2,500 for freight from California, and a whopping $1,500 for “commissioning, including bottom paint.” At that rate, we’d be tempted to buy a trailer and do the commissioning and painting ourselves—if not to pick up the boat at the factory and save the freight as well.

It would be nice to see an update next time around on the C250 Wing Keel version. Based on what I read in the article, it seems like a completely different boat. My 2004 came from the factory with a Yanmar 1GM and a SD 20 sail drive, 53 Liter diesel tank, large water tank storage under the V berth (where the batteries are mounted as well) etc. A comparison between the sailing characteristics of the water ballast versus the wing keel would be interesting. Thanks – enjoying the magazine BTW.

Same here.. Geez… the possible improvements in the 2004 model

would be unavailable to a reader. They are left with an unfavourable impression based on the earlier waterbalast configuration..

Perhaps there is much validity attached to this review..Sail cut, anchor locker size, placement , and capacity of winches, size of berth, running rigging controls are critical but ..perhaps some improvements in the later models, Full keel as well, may salvage some of the reputation Catalina has worked so hard to achieve as the Model evolved..I enjoy our trailerable wing keel model 2004 up here on the Great Lakes and appears to have many improvements over the earlier waterbalast 250..

Appreciate your magazine..

Alan Carlisle

I read through your report on the 1996 Catalina 250 and was very disappointed to hear how poor you rated the boat. I have owned a 1994 MacGregor 26S and seemed somewhat satisfied but was told by many sources that the Catalina 250 was a better boat. This was probably a subjective evaluation but now I am second guessing whether I should purchase a Catalina. For the money, is the Catalina 250 better value then the MAC 26s.