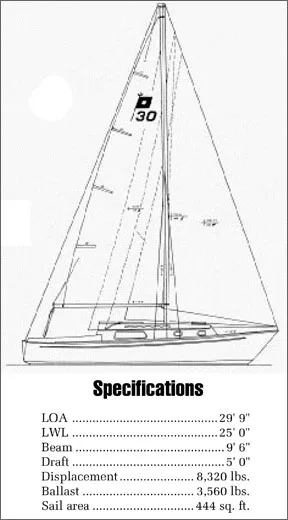

The Bill Shaw-designed Pearson 30 entered production in late 1971. By January 1, 1980, 1,185 of the fin-keel, spade-rudder sloops had been built in the company’s Portsmouth, Rhode Island plant. Peak production years were 1973 and 1974, with about 200 boats produced in each of those years. Production tapered off to about 70 boats per year in the last three years of production, and the P30 was discontinued with the 1981 models, later replaced in the Pearson line by the Pearson 303.

The Pearson 30 was designed as a family cruiser and daysailer with a good turn of speed. The boat is actively raced throughout the country, however, with some holding IOR certificates, and many more racing in PHRF, MORC, and one-design fleets.

The P30’s swept-back fin keel and scimitar-shaped spade rudder are fairly typical of racing boat design from the late 1960s and early 1970s but look somewhat dated next to today’s high aspect ratio fin keels and rudders.

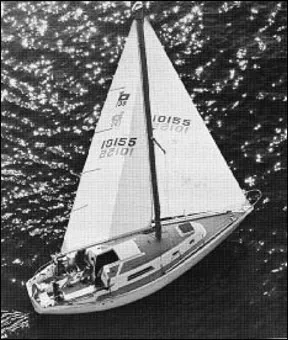

The boat’s underwater shape is somewhat unusual, The hull is basically dinghy-shaped. The sections aft of the keel are deeply veed, however, so that deadrise in the forward and after sections of the boat is similar. Coupled with a fairly narrow beam by today’s standards, this provides a hull form which is easily balanced when the boat is heeled—an important consideration in this relatively tender 30-footer. Above the water the Pearson 30 carries out the standard Pearson credo—moderation in all matters. The hull has a moderate amount of conventional sheer curvature with modest overhangs at bow and stern. The cabin trunk is well proportioned but is of necessity somewhat high to achieve headroom in a small boat without excessive freeboard. Styling is clean and modern with—thankfully—no attempt to incorporate “traditional” detailing. The boat’s appearance may not stir the soul, but neither will it offend the eye.

The Pearson 30 has a well-proportioned masthead rig. The mainsail comprises 44% of the working sail area, more than is found on many modern “racercruisers,” but a reasonable proportion for a true multi-purpose boat.

Base price in 1971 was $11,750. By November 1979, base price had jumped to $28,300. The builder’s option list included about $8,000 worth of goodies for the gadget addict, including wheel steering, a LectraSan toilet system, and a $500 stereo system.

Average 1979 sailaway price was about $35,000. The average 1992 price for that 1979 model is $20-$21,000.

After years of using the Palmer 22 horsepower and 30 horsepower Atomic Four gasoline engines, the late model Pearson 30s came with a two-cylinder Universal diesel, which weighs about the same as the Atomic Four.

Construction

Pearson is one of the oldest fiberglass boatbuilders in the country. Their Triton and Alberg 35 are two of the classic “modern” boats. With over 20 years of fiberglass boatbuilding experience, Pearson has solved most of the construction problems that seem to plague some builders.

The layup schedule of the Pearson 30 did not change during the production life of the boat. The hull structure is a hand layup in a one-piece mold of alternating plies of 1 1/2-ounce mat and 18-ounce woven roving. Two layers of omni-directional mat are used beneath the gelcoat to prevent “print through” of the first roving layer, an unsightly and unfortunately common problem with some builders.

Below the waterline, the Pearson 30 hull is a solid seven-ply layup, yielding an average bottom thickness of .29″. Along the keel, the plies from each side are overlapped, doubling the thickness in this critical area. The topside skin is five plies of mat and roving, with an average thickness of .21″. The deck is a fiberglass/balsa sandwich.

The hull-to-deck joint is made by glassing together the external flanges of the hull and deck. This chemical bond is backed up by stainless steel self-tapping screws at intervals of approximately 4″. The flanges are covered by an extruded plastic rubrail holder, covered by the familiar Pearson soft vinyl rubrail.

One Pearson 30 owner who races his boat reported that the hull-to-deck joint had opened slightly at the bow from excessive headstay tension. No other owner reported this problem, and examination of a large number of Pearson 30s failed to reveal another hull with this problem. Excessive headstay and backstay loading is often found in racing boats and can damage any boat not designed for this type of loading.

The Pearson 30’s spade rudder has provided the only recurrent problem with the boat. The rudder stock consists of a thick-walled stainless steel pipe. The stock enters the hull through a slightly larger diameter fiberglass rudder tube, which projects above the waterline to the cockpit sole, eliminating the need for a stuffing box. The rudder stock rides in two Delrin bushings, one at the top and one at the bottom of the fiberglass rudder tube. Wear in these Delrin bushings causes play to develop in the rudder stock. This wear can be accelerated by failing to tie off the tiller when the boat is at rest, thus letting the stock turn from the natural motion of the boat.

The bushings are owner-replaceable when the boat is hauled out, requiring removal of the tiller fitting and dropping the rudder through the bottom of the boat. The bushings can then be pried out and replaced.

The frequency with which rudder bushings must be replaced varies with the amount of use the boat receives. Pearson considers the bushings an item of routine maintenance. We would recommend that they be replaced whenever any slop develops. About 30% of the boats we examined showed significant bushing wear.

We also found annoying and excessive play in the tiller fitting which might sometimes be confused with bushing wear. Correcting this requires shimming or bushing the cast aluminum tiller socket.

The first Pearson 30s had an aluminum pipe rudder stock rather than stainless. Several rudders broke off as a result of corrosion at the narrow gap between rudder and hull. To Pearson’s credit, the firm recalled and replaced the rudders on the approximately 200 boats built with aluminum stocks. The error in using aluminum stocks was far outweighed by the company’s willingness to correct a potentially serious problem.

The Pearson 30’s 3,560 lbs of lead ballast is encapsulated in the fiberglass keel molding, This avoids the necessity of keel bolts but makes the keel more vulnerable to grounding damage.

The deck-stepped, polyurethane-painted aluminum mast is supported by the main cabin bulkhead and an oak compression column. This column is glassed into the top of the keel.

If coaming-mounted genoa turning blocks are installed—and they are necessary for genoas larger than 150%—it is essential that large backing plates be used. Some of these blocks which were improperly installed by owners have pulled through the coamings, which are a relatively thin solid fiberglass molding.

Through hull fittings appear to be bedded with silicone, a less than ideal choice for underwater fittings. Proper seacocks or gate valves are installed in all underwater openings, although none are installed with backing blocks, which is highly recommended. Chainplates, where visible, are properly bolted to primary structural bulkheads.

Much of the interior construction is bonded to the hull, including the molded fiberglass floor pan and molded headliner. Molded hull liners are relatively expensive, and are seen less and less frequently in modern stock boat construction. Interior surfaces are teak- or Formica-covered plywood. Exposed plywood edges are covered by glued-on plastic trim, which, we noted, has often pulled off, even on new boats.

Seat back lockers have friction catches, which unless properly aligned can let the seat back/locker doors come open when the boat is heeled. The cabin sole is non-skid fiberglass. Exposed interior fiberglass surfaces are now covered by foam-backed tan basket weave vinyl which enhances appearance.

Pearson hull strength has never been questioned. Their boats tend to have slightly heavier scan’tlings than average, which is hardly a shortcoming. The construction of all their boats, including the Pearson 30, is of above average stock boat quality.

Handling Under Sail

The Pearson 30 is an active sailor’s boat. We find it responsive, and a pleasure to sail. It is also tender, and very sensitive to the proper sail combination. All owners responding consider the boat to be somewhat “tippy.” The P30 does, in fact, put the rail under quite easily.

In 15 knots apparent wind, we find that the boat is almost overpowered with the full main and 150% genoa. Gusts of 12-14 knots bury the rail, slowing the boat. The P30 does not, however, carry any substantial weather helm even when overpowered. Any tendency to round up or spin out can usually be controlled by a strong hand on the tiller and easing the mainsail.

As you would expect in a dinghy-hulled, spaderudder fin-keeler, the boat is quick in tacks. It is so quick, in fact, that the jib sheet winch grinder is likely to be growled at by the skipper for being too slow. The winch grinder is also handicapped by the difficulty of his bracing himself properly to exert full power on the winches, a common problem on production boats of almost any size. We strongly recommend the optional Lewmar #40 jib sheet winches, whether the boat is used for racing or cruising. The standard halyard winches are perfectly adequate. The optional roller-bearing mainsheet traveler is practically a must for effective trim of the mainsail although it does reduce cockpit room.

Although the Pearson 30 was not specifically designed for racing, some of the boats have had very successful racing careers. Pete Lawson’s Syrinx won the Three-quarter Ton North American Championship in 1972. Under IOR Mk IIIA, the boat’s average rating has dropped nearly two feet, making the boat rate just over Half Ton. The boat is still a successful club racer and is hotly raced as a one-design class in some areas, including Chesapeake Bay. Pearson 30s also race in MORC classes, and the boat has been measured for USYRU Measurement Handicap System (MHS) for hull standardization.

Owners report that typically only about 10% of their sailing time is devoted to racing. Another 10% is spent cruising, while fully 80% of sailing time is spent daysailing.

The boat will be sailed quite differently by racers and cruisers. Experienced Pearson 30 racers keep the boat moving by reefing the main and carrying on with larger headsails as the breeze pipes up.

Cruisers will find it more comfortable to sail with smaller headsails and more mainsail even though there will be some sacrifice in performance on the wind. A good selection of headsails—at least a 150% genoa, a #3 genoa, and a working jib—is necessary. A small heavy-weather jib would be a good idea for boats that cruise in exposed waters.

Handling Under Power

The Pearson 30’s underwater configuration creates a boat that maneuvers remarkably well under power. The P30 easily turns in a circle its own length in diameter. The standard two-cylinder Universal diesel pushes the boat well, albeit with some vibration, although it lacks the power of the old Atomic Four when punching through a chop.

A strong arm on the tiller is required when backing down under power. “It’s a tough boat to handle in reverse. It can tear your arm off,” said one experienced Pearson 30 sailor. The aft-raking unbalanced rudder will easily go hard over if too much helm is applied while backing down, and an unprepared or off-balance helmsman could be thrown off his feet by the sweeping tiller under these conditions. Applying minimum rudder corrections reduces this tendency, but a rudder of this type, which is free to rotate through 360 degrees, can pose a real threat to the unwary.

Deck Layout

Certain compromises in deck layout are inherent in almost any 30-footer; the Pearson 30 is no exception. The shrouds hamper access to the foredeck, so that it is easier to walk on the cabin top to go forward than along the sidedecks. This is almost a universal shortcoming in boats of this size, as the requirements of interior living space necessitate a large cabin trunk and relatively narrow sidedecks.

The bow cleat is located well forward and is adequate for the size of lines likely to be used on the boat. However, we would prefer two bow cleats, nearly side by side, in the same location. This is particularly useful in boats which spend a major amount of their lives tied to a dock, as the rule of thumb is that the dockline which needs adjusting is always the bottom line on any cleat.

The vinyl rubrail around the hull-to-deck joint presents a problem when anchoring the Pearson 30. It will undoubtedly be chafed by the anchor line. Redesign or relocation of the bow chocks would be necessary to correct this potential chafe problem.

The large starboard cockpit locker is designated as the boat’s sail locker. We recommend that the locker be put to its intended use. The locker is so deep that small items would end up in a heap in the bottom almost out of reach if they were stored here. Space in the lazarette locker—a natural place for fenders, docklines, and sheets—is limited by the engine exhaust hose. Rerouting this hose would increase the usefulness of this space.

The large cockpit seats four adults comfortably for daysailing and six if they are active enough to stay out of the way of the tiller and the mainsheet. The 4′ long tiller definitely encroaches on the cockpit living space. We would normally be reluctant to recommend wheel steering for a high-performance 30-footer: it would, however, increase cockpit space and might reduce the idiosyncrasies created by the spade rudder when handling the boat under power.

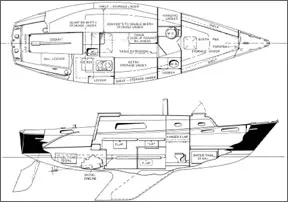

Interior

The Pearson 30 has a light, roomy interior for a boat of its size. In the 1980 model, all four ports in the head and forward cabin are of the opening type, greatly improving ventilation, particularly when coupled with the optional, but recommended foredeck-mounted cowl ventilator.

The overhead hatch in the forward cabin is basically a ventilation hatch and is too small for either sails or emergency exit. Anchor storage is awkward without a foredeck anchor well, a welcome addition to many more recently designed boats the size of the Pearson 30.

The 22-gallon water tank and the standard holding tank occupy much of the space under the forward double berth. This double berth is actually the entire forward cabin, and can be closed off from the full width head by double doors. The standard marine toilet is equipped with a proper vented loop. The head wash basin is tucked under the deck and is difficult to use for anyone with less agility than a contortionist. The location of this wash basin is the only serious flaw in the otherwise functional head compartment.

The P30’s main cabin is large and comfortable, with capacious storage above, behind, and below the settees. Owners may find these storage spaces more useful if they are subdivided by partitions to prevent gear stored in one locker from ending up in another.

The under-settee and under-galley lockers cannot be considered dry storage unless the bilge is kept bone dry. Although the lockers are sealed to the bilge at the bottom, owners report that, with their boat heeled, bilge water finds its way into the lockers by running up the inside of the hull behind locker partitions, then down into storage spaces. Most dinghy-hulled boats lack real bilge space or a sump, and as little as a gallon of water in a boat of this type can be annoying.

It is unfortunate that a large number of berths has become a criterion for livability in modern boats. In the past, a 40-footer was likely to have four or five berths. Now six berths are standard on a 30-footer, including the Pearson 30, seven on a 35-footer, and eight on a 40-footer.

Cruising longer than overnight with six on a boat the size of the Pearson 30 is a sure way to terminate friendships and wreck marriages. No responding Pearson 30 owner reported cruising with more than four people on a regular basis.

The standard fold-down cabin table is a practical solution on a boat of this size. The optional slide-out chart table limits room over the quarterberth and lacks the fiddles which are necessary because of its slanted surface.

The Pearson 30 galley is typical of 30-footers. As much as possible is jammed into a necessarily small space. The deep lockers behind the stove and icebox will probably be partitioned into several smaller compartments by the moderately handy owner. Annoyingly, a short person has a hard time reaching the depths of the icebox, particularly if the stove is in use.

We cannot recommend the self-contained alcohol stoves almost always installed on the Pearson 30 and other boats of this size. There is a very real and well-documented risk of explosion if the stove must be refueled while hot. It is the fault of the marine stove industry—and an uninformed consuming public— that these potentially dangerous stoves are still used on many boats.

The galley sink and spigot partially block the companionway. The top companionway step is actually the lid of a nifty storage box, handy for winch handles, spare blocks, and tools.

Engine access is via the companionway steps, which lift out to expose the front of the engine. Two slatted doors in the quarterberth provide additional if awkward access to the engine and fuel tank under the cockpit. There is no soundproofing in the engine compartment.

The new, smaller diesel engine is more accessible for service than the old Atomic Four. It has molded fiberglass engine beds and drip pan, an excellent idea, although some engine vibration is transferred to the hull despite the flexible engine mounts and shaft coupling.

It is rare for a 30-footer to have good engine access. The Pearson 30 is no better than average in this respect.

Despite the above shortcomings, the P30 is highly livable. The advertised 6′ 1″ headroom is really an honest 5 11″ in the main cabin. Achieving good headroom in a 30-footer without serious compromises in appearance is nearly impossible. The Pearson 30 comes as close to achieving this as any boat we have seen in its class.

Conclusions

The Pearson 30 was an industry success story. The boat is fast and responsive. Finish quality is above average. The interior is comfortable and reasonably roomy within the limitations inherent in a 30-footer. Many of the minor design problems can be corrected by the imaginative and handy owner who enjoys tinkering.

Pearson has a reputation for building solid, middle-of-the-road boats: a deserved reputation well in evidence in the P30. The Pearson 30 would be an excellent choice of boat for the aggressive and self-confident beginning sailor who desires high performance for daysailing or club-level racing as well as for reasonably comfortable short-term cruising. It is not the boat for the timid sailor, male or female. The family with two children will find it a comfortable cruiser. Sailors with friends who enjoy spirited sailing and who don’t mind frequent sail changes will also find it a good choice for daysailing and local racing.

The long production run and continued popularity have created a boat with few inherent major problems and high resale value. The Pearson 30 is a good investment.

Why does the encapsulated lead in the keel make it more prone to damage in groundings?

“The Pearson 30’s 3,560 lbs of lead ballast is encapsulated in the fiberglass keel molding, This avoids the necessity of keel bolts but makes the keel more vulnerable to grounding damage.”