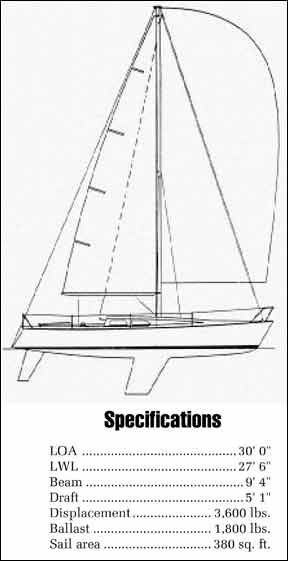

The Olson 30 is of a breed of sailboats born in Santa Cruz, California called the ULDB, an acronym for ultra light displacement boat.ULDBs are big dinghies—long on the waterline, short on the interior, narrow on the beam, and very light on both the displacement and the price tag. ULDBs attract a different kind of sailor—the type for whom performance means everything.

For some yachting traditionalists, the arrival of ULDB has been a hard pill to swallow. Part of this is simple resentment of a ULDB’s ability to sail boat for-boat with a racer-cruiser up to 15′ longer (and a whole lot more expensive). Part of it is the realization that, to sail a ULDB might mean having to learn a whole new set of sailing skills. Part of it is a reaction to the near-manic enthusiasts of Santa Cruz, where nearly 100 ULDBs race for pure fun—without the help of race committees, protest committees, or handicaps (in Santa Cruz, IOR is a dirty word). And part of the traditionalists’ resentment is their gut feeling that ULDBs aren’t real yachts.

In 1970, Californian George Olson tried an experiment and created the first ULDB. He thought if he took a boat with the same displacement and sail area as a Cal 20, but made it longer and narrower, it might go faster. The boat he built was called Grendel and it did go faster than a Cal 20, much faster than anyone had expected. The plug for Grendel was later widened by Santa Cruz boatbuilder Ran Moors, and used to make the mold for the Moore 24, a now-popular ULDB one-design.

In the meantime, George Olson had joined up with another Santa Cruz builder by the name of Bill Lee, and together they designed and built the Santa Cruz 27. Olson also helped Lee build his 1977 Transpac winner Merlin, a 67′, 20,000 pound monster of a ULDB (she was subsequently legislated out of theTranspac race). Then Olson and several other of Lee’s employees started their own boatbuilding firm (in Santa Cruz, of course) called Pacific Boats. The first project for Pacific Boats was the Olson 30, which was put into production in 1978. Pacific Boats later became Olson/Ericson, and produced a 25 and a 40. The latest incarnation of the 30 is called the 911.

Construction

Some people wonder how ULDBs can be built so light, yet still be seaworthy offshore. The answer is three-fold: first, a light boat is subjected to lighter loads, when pounding through a heavy sea, than a boat of greater displacement. Second, there is a tremendous saving in weight with a stripped-out interior. Third, as a whole, ULDB builders have construction standards that are well above average for production sailboats. The ULDB builders say that their close proximity to each other in Santa Cruz combined with an open sharing of technology has enabled them to achieve these standards.

The Olson 30 is no exception. The hull and deck are fiberglass vacuum-bagged over a balsa core. The process of vacuum-bagging insures maximum saturation of the laminate and core with a minimum of resin, making the hull light and stiff. The builder claims that they have so refined the construction of the Olson 30 that each finished hull weighs within 10 pounds of the standard. The deck of the Olson does not have plywood inserts in place of the balsa where winches are mounted, instead relying on external backing plates for strength.

The hull-to-deck joint is an inward turned overlapping flange, glued with a rigid compound called Reid’s adhesive, and mechanically fastened with closely spaced bolts through a slotted aluminum toerail. This provides a strong, protected joint, seaworthy enough for sailing offshore. We would prefer a semi-rigid adhesive, however, because it is less likely to fracture and cause a leak in the event of a hard collision. The aluminum toerail provides a convenient location for outboard sheet leads, but is painful to those sitting on the rail.

The Olson 30’s 1,800 pound keel is deep (5.1′ draft) and less than 5″ thick. Narrow, bolted-on keels need extra athwartships support. The Olson 30 accomplishes this with nine 5/8″ bolts and one 1″ bolt (to which the lifting eye is attached). The lead keel is faired with auto body putty and then completely wrapped with fiberglass to seal the putty from the marine environment. Too many builders neglect sealing auto body putty-faired keels, and too many boat owners then find the putty peeling off at a later date. The Olson’s finished keel is painted, and, on the boats we have seen, remarkably fair.

The keel-stepped, single-spreader, tapered mast is cleanly rigged with 5/32″ Navtec rod rigging and internal tangs. The mast section is big enough for peace of mind in heavy air. The halyards exit the mast at well-spaced intervals, so as not to create a weak spot.The shroud chainplates are securely attached to half-bulkheads of 1″ plywood. In addition, a tie rod attaches the deck to the mast, tensioned by a turnbuckle. While this arrangement should provide adequate strength, we would prefer both a tie rod and a full bulkhead that spans the width of the cabin so as to absorb the compressive loads that the tension of the rig puts on the deck.

The rudder’s construction is labor intensive, but strong. Urethane foam is hand shaped to templates, then glued to a 4″ thick solid fiberglass rudder post. The builder prefers fiberglass because it has more “memory” than aluminum or steel. Stainless steel straps are wrapped around the rudder and mechanically fastened to the post. Then the whole assembly is faired, fiberglassed, and painted.

Handling Under Sail

For those of you who agonize over whether your PHRF rating is fair, consider the ratings of ULDBs. The Santa Cruz 50 rates 0; that’s right—zero. The 67′ Merlin has rated as low as minus 60. The Olson 30 rates anywhere from 90 to 114, depending on the local handicapper. Olson 30 owners tell us that the boat will sail to a PHRF rating of 96, but she will almost never sail to her astronomical IOR rating of 32′ (the IOR heavily penalizes ULDBs).

ULDBs are fast. They are apt to be on the tender side, and sail with a quick, “jerky” motion through waves. Instead of punching through a wave, they ride over it. You may get to where you are going fast, but with the motion of the boat and the Spartan interior you won’t get there in comfort. Olson 30 owners tell us that they do far less cruising and far more racing that they had expected to do when they bought the boat. They say it’s more fun to race because the boat is so lively.

Like most ULDBs the Olson 30 races best at the extremes of wind conditions—under 10 knots and over 20 knots. Although her masthead rig may appear short, it is more than powerful enough for her displacement. Owners tell us that she accelerates so quickly you can almost tack at will—a real tactical advantage in light air. In winds under 10 knots they say she sails above her PHRF rating both upwind and downwind.

In moderate breezes it’s a different story. Once the wind gets much above 10 knots, it’s time to change down to the #2 genoa. In 15 knots, especially if the seas are choppy, it’s very difficult for the Olson 30 to save her time on boats of conventional displacement, according to three-time national champ Kevin Connally. The Olson 30 is always faster downwind, but even with a crew of 5 or 6, she just cannot hang in there upwind.

In winds above 20 knots, the Olson 30 still has her problems upwind, but when she turns the weather mark the magic begins. As soon as she has enough wind to either surf or plane, the Olson 30 can make up for all she loses upwind, and more. The builder claims that she has pegged speedometers at 25 knots in the big swells and strong westerlies off the coast of California. That is, if the crew can keep her 1800 pound keel under her 761 sq. ft. spinnaker.

The key to competitiveness in a strong breeze is the ability of the crew. Top crews say that, because she is so quick to respond, they have fewer problems handling her in heavy air than a heavier, conventional boat. However, an inexperienced crew which cannot react fast enough can have big problems. “The handicappers say she can fly downwind, so they give us a low rating (PHRF), but they don’t understand that we have to sail slow just to stay in control,” complained the crew of one new owner.

Like any higher performance class of sailboat, the Olson 30 attracts competent sailors. Hence, the boat is pushed to a higher level of overall performance, and the PHRF rating reflects this. An inexperienced sailor must realize that he may have a tougher time making her sail to this inflated rating than a boat that is less “hot.” The two most common mistakes that new Olson 30 owners make are pinching upwind and allowing the boat to heel excessively. ULDBs cannot be sailed at the 30 degrees of heel to which many sailors of conventional boats are accustomed. To keep her flat you must be quick to shorten sail, move the sheet leads outboard, and get more crew weight on the rail. You can’t afford to have a person sitting to leeward trimming the genoa in a 12-knot breeze. To keep her thin keel from stalling upwind, owners tell us it’s important to keep the sheets eased and the boat footing.

Being masthead-rigged, the Olson 30 needs a larger sail inventory than a fractionally rigged boat. Class rules allow one mainsail, six headsails (jibs and spinnakers) and a 75% storm jib. Owners who do mostly handicap racing tell us they often carry more than six headsails.

Handling Under Power

Only a few of the Olson 30s sold to date have been equipped with inboard power. This is because the extra weight of the inboard and the drag of the propeller, strut and shaft are a real disadvantage when racing against the majority of Olson 30s, which are equipped with outboard engines. The Olson 30 is just barely light enough to be pushed by a 4-5 hp outboard, which is the largest outboard that even the most healthy sailor should be hefting over a transom. It takes a 7.5 hp. outboard to push the Olson 30 at 6.5 knots in a flat calm. The Olson’s raked transom requires an extra long outboard bracket, which puts the engine throttle and shift out of reach for anyone much less than 6′ tall: “A real pain in the ass,” said one owner. Storage is a problem, too. Even if you could get the outboard through the stern lazarette’s small hatch, you wouldn’t want to race with the extra weight so far aft. So most owners end up storing the outboard on the cabin sole.

The inboard, a 154 pound, 7 hp BMW diesel, was a $4,500 option. Unlike most boats, the Olson 30 will probably not return the investment in an inboard when you sell the boat, because it detracts from the boat’s primary purpose—racing.

Without an inboard there’s a problem charging the battery. Owners who race with extensive electronics have to take the battery ashore after every race for recharging. If the Olson 30 weren’t such a joy to sail in light air, and so maneuverable in tight places, the lack of inboard power would be a serious enough drawback to turn away more sailors than it does.

Deck Layout

In most respects, the Olson 30 is a good sea boat. Although the cockpit is 6 1/2′ long, the wide seats and narrow floor result in a relatively small cockpit volume, so that little sea water can collect in the cockpit if the boat is pooped or knocked down. However, foot room is restricted, while the width of the seats makes it awkward to brace your legs on the leeward seat. The seats themselves are comfortable because they are angled up and the seatbacks are angled back. There are gutters to drain water off the leeward seat. The long mainsheet traveler is mounted across the cockpit—good for racing but not so good for cruising.

The Olson 30’s single companionway drop board is latchable from inside the cabin, a real necessity in a storm offshore. A man overboard pole tube in the stern is standard equipment. Teak toerails on the cockpit coaming and on the forward part of the cabin house provide good footing, and there are handholds on the aft part of the cabin house.

The tapered aluminum stanchions are set into sockets molded into the deck and glassed to the inside of the hull, a strong, clean, leak-proof system. However, the stanchions are not glued or mechanically fastened into the sockets. If pulled upwards with great force they can be pulled out. We feel this is a safety hazard. Tight lifelines would help prevent this from happening, but most racing crews tend to leave them slightly loose so as to be able to lean farther outboard when hanging over the rail upwind. If the stanchions were fastened into the sockets with bolts or screws they would undoubtedly leak. A leakproof solution to this problem should be devised and made available to Olson 30 owners.

The cockpit has two drains of adequate diameter.

The bilge pump, a Guzzler 500, is mounted in the cockpit. The Guzzler is an easily operated, high capacity pump. However, its seeming fragility worries us. As is common on most boats, the stern lazarette is not sealed off from the rest of the interior. If the boat were pooped or knocked down with the lazarette open, water could rush below through the lazarette relatively unrestricted. As the Olson 30 has a shallow sump, there is little place for water to go except above the cabin sole.

A “paint-roller” type non-skid is molded into the Olson 30’s deck. It provides excellent traction, but it is more difficult to keep clean than conventional patterned non-skid.

The Olson 30 is well laid out with hardware of reasonable, but not exceptional, quality. All halyards and pole controls lead to the cockpit though Easylock I clutch stoppers. The Easylocks are barely big enough to hold the halyards; they slip an inch under heavy loads. Older Olsons were equipped with Howard Rope Clutches.

The primary winches, Barient 22s, are also barely adequate. Some owners we talked to had replaced them with more powerful models. Schaefer headsail track cars are tandard equipment. One owner complained that he had to replace them with Merrimans because the Schaefers kept slipping. Leading the vang to either rail and leading the reefs aft is also recommended. The mast partner is snug, leaving no space for mast blocks. The mast step is movable to adjust the prebend of the spar. The partner has a lip, over which a neoprene collar fits. The collar is hoseclamped to the mast. This should make a watertight mast boot. However, on the boat we sailed, the bail to which the boom vang attached obstructed the collar, causing water to collect and pour into the cabin.

The yoked backstay is adjustable from either quarter of the stern, one side being a 2-to-1 gross adjustment and the other side being an 8-to-1 fine tune. A Headfoil II is standard equipment. There is a babystay led to a ball-bearing track with a 4-to-1 purchase for easy adjustment. The track is tied to the thin plywood of the forward V-berth with a wire and turnbuckle. On the boat we sailed, the pad eye to which the babystay tie rod is attached was tearing out of the V-berth.

There is a port in the deck directly over the lifting eye in the bilge. This makes for quick and easy drysailing. The Olson 30, however, is not easily trailered; her 3600 pounds is too much for all but the largest cars, and her 9.3′ beam requires a special trailering permit.

Belowdecks

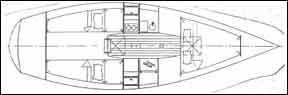

The Olson 30 is cramped belowdecks. Her low freeboard, short cabin house and substantial sheer may make her the sexiest-looking production boat on the water, but the price is headroom of only 4′ 5″. There is not even enough headroom for comfortable stooping; moving about below is a real chore.

To offset the confinement of the interior, the builder has done all that is possible to make it light and airy. In addition to the lexan forward hatch and cabin house windows, the companionway hatch also has a lexan insert. The inside of the hull is smoothly sanded and finished with white gelcoat. There are no full height bulkheads dividing up the cabin. All of the furniture is built of lightweight, light-colored, 3/8″ thick Scandinavian plywood of seven veneers.

The joinerwork is above average and all of the bulkhead and furniture tabbing is extremely neat. There isn’t much to the Olson 30’s interior, but what there is has been done with commendable craftsmanship. The interior wood is fragile, though. There are several unsupported panels of the 3/8″ plywood; if someone were to fall against them with much force it’s likely they would fracture. The cabin sole is narrow, and with the lack of headroom the woodwork is especially susceptible to being dinged and scratched from equipment like outboard engines. Once the finish on the wood is broken, it quickly absorbs water, which collects in the shallow bilge.

The Olson 30 is not a comfortable cruiser. Even after you’ve taken all the racing sails ashore, the belowdecks is barely habitable. To save weight the quarterberths are made of thin cushions sewn to vinyl and hung from pipes. These pipe berths are comfortable, but the cushions are not easily removed. Should they get wet it’s likely they would stay wet for quite a while. Two seabags are hung on sail tracks above the quarter berths, which should help to insure that some clothes always stay dry.

Just forward of each quarterberth is a small uncushioned seat locker. Behind each seat is a small portable ice cooler. In one seat locker is the stove, an Origo 3000 which slides up and out of the locker on tracks. The Origo is a top-of-the-line unpressurized alcohol stove, but to operate it the cook must kneel on the cabin sole. To work at the navigation station, which is in front of the starboard seat, you must sit sideways. In front of the port seat is the lavette, with a hand water pump and a removable, shallow drainless sink. Drainless sinks eliminate the need for a through-hull fitting, a good idea; but they should be deep, not shallow.

The portable head is mounted under the forward V-berth, which we think is totally unsuitable for a sailboat. Who wants a smelly toilet under his pillow? Although there are curtains which can be drawn across the V-berth, we think human dignity deserves an enclosed head, especially on a 30′ boat. The Vberth is large and easy to climb into, but there are no shelves above it nor a storage locker in the empty bow. In short, if you plan to cruise for more than a weekend you had better like roughing it.

Conclusions

For 30-footers, the price of an Olson 30 is cheap; but for boats of similar displacement, it’s damned expensive.

What do you get for the money? You get a boat that is well-built, seaworthy, and reasonably well laid out. You get a boat that, in light air, will sail as fast as boats costing nearly twice as much. Downwind in heavy air, you have a creature that will blow your mind and leave everything shy of a bigger ULDB in your wake. If you spend all of your sailing time racing in a PHRF fleet in an area where light or heavy air dominates, the Olson 30 will probably give you more pleasure for your dollar than almost anything afloat.

However if you race often in moderate air or enjoy more than a very occasional short cruise, you are likely to be very disappointed. Before you consider the Olson 30, you must realistically evaluate your abilities as a sailor. There’s nothing worse than, after finding out that you can’t race a boat to her potential, knowing that she is of little use for the other aspects of our sport.