Occasionally we hear from a sufficient number of owners requesting a Practical Sailor report on their boat that we cannot forever resist their supplications. A check of the files revealed that we already had a good deal of information on the Niagara 31 & 35. And when we asked current owners for their input, the response was considerable. In fact, we have enough paper to write separate reports, but because these two boats were built during the same approximate years, and represent interesting contrasts, we decided to combine the two in one article.

History

Hinterhoeller Yachts was founded by George Hinterhoeller in 1977, after he left C&C Yachts, the company he helped start during the previous decade. George’s career in boatbuilding is long and interesting, beginning first in Canada with his highly successful Shark, a lightning fast 24-footer. The story of C&C aside, Hinterhoeller Yachts built two distinctive lines—the Niagara and the Nonsuch, the latter with unstayed masts and wishbone booms. The company was placed in receivership in 1989 and purchased by Strategic Associates Inc. in 1990, which in 1993 consolidated production with C&C. When a 1994 fire destroyed part of the C&C plant, Hinterhoeller moved back to its former facilities. It closed the doors again in November 1995 and currently is out of business, which is too bad, because owners had nothing but good things to say about Hinterhoel-ler’s customer service.

George’s son, Richard Hinterhoeller, a partner in the company, told us:

“The business plan was to operate a shop with two production lines. The two models were to be a 30′ club racer/cruiser and a 35′ bluewater cruising boat. Both were to be sensible, timeless models. George had been impressed by the Aurora 40 from Mark Ellis and contracted him to design the Niagara 35. For the smaller boat, George sat on his C&C 30 and made a list of the 10 items which would take an already great boat and make it better. In his typical down-to-earth fashion, George added up the necessary lengths of berths, head, cockpit and galley, and ended up with a target length of 31 feet.”

The Designs

Best known for his big race boats, Argentinean designer German Frers drew the lines of the Niagara 31. The 35, as noted, was drawn by Mark Ellis, who also designed the Nonsuch line, and more recently, the Northeast 37 motorsailer. The 35 came first, in 1978, and about 300 were built before its run came to an end in 1995. The Niagara 31 was built between 1980 and 1984. A less popular 26-footer also was built, as well as a 42.

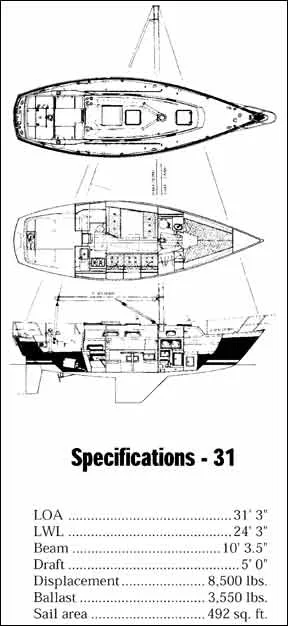

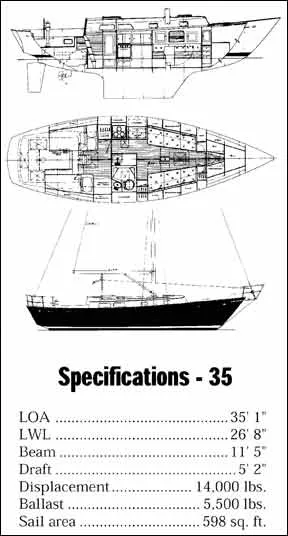

Based on their specifications, the 31 is the more lithe of the two, with a displacement to length (D/L) ratio of 266 and a very generous sail area to displacement (SA/D) ratio of 18.9. The 35 is definitely more of a cruiser with a D/L of 329 and a SA/D of 16.47.

This distinction is also evident in their underbodies, where the 31 has a much smaller fin keel than the 35’s long “cruising fin.” The 31 has a large spade rudder that rises to meet the counter, and there is a partial skeg. The 35, interestingly, has no skeg for its balanced rudder. Years ago, we asked Mark Ellis why. He shrugged and said something about better handling. While most cruisers look to at least a skeg

to support and protect the rudder and perhaps to increase the lateral plane for directional stability, years later we found it interesting that Steve Dashew (Deerfoot and Sundeer lines of performance cruisers) prefers the spade rudder for heavy weather handling. So, there is no right answer on the issue of rudder protection vs. handling, but in a full-blown cruising boat, we’d still opt for support and protection.

Then again, despite numerous passages to the Caribbean and South Pacific, the Niagara 35 is not really a round-the-world type—among other things, it’s considered too small by many of today’s bluewater sailors.

Both the 31 & 35 are described as having somewhat veed hull shapes, which was a characteristic of IOR designs during the late 70s and early 80s; while it increases wetted surface area, it should be more seakindly than a more modern flat bottom boat.

Nevertheless, several owners described their 31s as having “flat bottoms” that don’t “cut the waves” and tend to pound a bit.

Construction

Hinterhoeller Yachts, like C&C, liked to use balsa coring for its light weight and rigidity. Both the Niagara 31 and 35 have it in the hull and deck. Unidirectional rovings were used and all structural bulkheads were bonded to the hull. Ballast is external lead bolted to a reinforced sump. Berth faces were molded but there was much wood used, including teak sole and a teak inlay in the 35’s molded overhead. Hardware quality was good, using, for example, Barient (later Lewmar) winches, Navtec rod rigging, Atkins & Hoyle hatches and, in the words of one 35 owner, “massive chocks and cleats.”

Owners generally rate construction as excellent, often citing Hinterhoeller’s reputation as a prime reason for buying. We received a few comments about gelcoat cracking and leaks around portlights and chainplates, with its attendant saturation of the balsa coring, but this is to be expected with any fiberglass boat. We had no complaints about the hull/deck joint, print-through or anything structural. One owner did say that the mast “rests on stringers made of built-up plywood laminates,” which he watches with a careful eye, though no problems have occurred. Another 31 owner complained of wild mast pumping, but we cannot imagine that condition being typical—something else is awry.

Accommodations

The 35 was introduced with an innovative interior dubbed the “Classic,” in which the forepeak is devoted to stowage (workbench, shelves, seat and lockers), the settees and cabin table are somewhat farther forward than normal, and the head and owners stateroom (with a double and single berth) are aft.

Many owners said the uniqueness of this layout was a factor in their purchase. Later, the more conventional “Encore” layout provided an offset double berth forward, with a quarter berth and U-shaped galley aft. Both seem popular with their owners, for different reasons.

Layout of the 31 is straightforward, as can be seen in the drawing: V-berth, head, dinette and galley. A 6′ 2″ owner said he has standing headroom in the main cabin, but has to stoop going forward.

Light and ventilation on the 31 are by means of a skylight and four fixed ports in the main cabin, plus two opening ports in the head and a hatch over the Vberths. The 35 has four fixed ports, six opening ports and four hatches besides the companionway, including one in the head and another over the galley (actual number seems to have changed over the years). Most owners rate ventilation as good.

The 35, by virtue of its size advantage, naturally received more glowing remarks for livability than the 31. One owner said it is the “perfect liveaboard for a close couple.” A few owners, however, said the berths are “tight.” Settee lengths in the Classic model, however, are 6′ 7″ and the double aft berth is 6′ 4″. (We do not have widths on file.) Headroom is 6’4″ in the main cabin, 6′ 2″ in the aft cabin (Classic model). We like the offset double V-berth of the Encore model, despite the fact that the person sleeping outboard has to crawl over his/her partner to get out. This arrangement allows for a dressing seat opposite, and tends to waste less space than a V-berth. One last remark about the two 35 interiors: fans of the Classic say that the V-berth is a lousy place to sleep…true, underway, but at anchor the best breezes come through the forward hatch. Aft cabins, no matter how well ventilated with portlights and hatches, are a bit stuffy.

Both boats feature oiled teak bulkheads and joinerwork with varnished pine strapping in book cases and above quarter berths, bi-fold doors and swiveling lights.

A Paloma instantaneous LPG water heater was offered as an option and universally liked by those who bought one. While they are still made, the company doesn’t warrant them for marine use (but who cares?). There are, of course, others on the market, most of which are more expensive without offering any real improvements.

While one owner said the craftsmanship of his Niagara is “Hinckley quality,” we think that’s stretching it, though the work is outstanding for what amounts to a production boat.

On Deck

Raised bulwarks on both boats give a far greater sense of security than mere toerails. Numerous 35 owners said that the high bow and 4″ bulwarks do much to keep the cockpit dry.

The 35 has a bowsprit with rod bobstay, which makes carrying anchors easy. The 31 was criticized by one owner for having an inadequate bow roller.

The cockpit of the 35 is quite large—great for lounging, but one owner said it’s too wide for bracing the feet when heeled.

The 35’s mainsheet traveler is out of the way, on the coachroof, but it doesn’t enable the helmsman easy access for trimming (always a trade-off!). On the 31, drawings show the traveler is end-of-boom on some boats, in the cockpit on others (another tradeoff).

End-of-boom is great for singlehanding, but doesn’t afford the control of mid-boom sheeting.

The 31 has no bridgedeck, while the 35 does—again, the coastal-offshore difference.

Hardware and stanchions have proper backing plates and deck reinforcement.

Performance

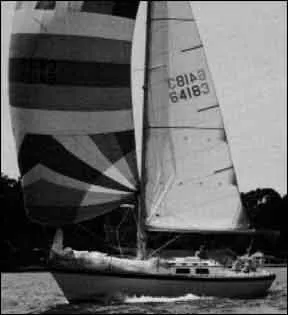

Where the 35 edges the 31 for cruising comfort, when it comes to performance, the 31 excels. Thanks to its big sloop rig with 492 square feet of sail, it does nicely in light airs. This also means reefing is required earlier—most owners say at about 15 knots.

And nearly all said so. Owners also report that the boat sails exceptionally well on all points; she’s stable, well-balanced and quick. “Will outpoint most racer-cruisers,” said the owner of a 1993 model. Another said, “This is a technical cruiser/racer, not for the beginner.”

The 35, by contrast, is not so fast nor closewinded. It’s smaller sailplan suits it more to breezy conditions and offshore work. One owner said speed improves dramatically over 8 knots of wind. It points respectably, though not as high (partly due to wide sheeting angles), and off the wind owners say she doesn’t track as well as she could. Overall, however, owners rate the boat’s handling as above average. And they say the 35 “cuts through the seas” better than the 31.

Auxiliary Power

Besides the unusual interior of the Niagara 35 Classic, perhaps the next most distinguishing feature of these boats is the standard Volvo diesel with Sail Drive. For those who don’t know, a sail drive is rather like the lower end of an outboard motor. Advantages of it include locating the prop somewhat farther forward, directing prop wash straight aft instead of down at an angle, and elimination of shaft logs and stuffing boxes. A major disadvantage is that the casting is aluminum, which requires good quality zincs to prevent corrosion, and meticulous inspection and replacement of them. And, in the case of these two Niagaras, the engines to which they are coupled are on the small side.

Now, some traditionalists like Tom Colvin think most boats have engines far too large, that they add unnecessary weight and burn excessive fuel and seldom are run at recommended rpm. On a sailboat, after all, primary locomotion should be sailpower, with the engine used only for close-quarter maneuvering.

Throughout the industry, customer preference, however, has been decidedly the opposite. We received numerous complaints about the small Volvo diesels initially offered with the Niagaras—a puny 13-hp. MD7A on the 31 and a 23-hp. MD11C diesel on the 35. A Westerbeke 21 was optional on the 31, and several different engines on the 35, including Westerbeke 27, 33, 40 and Universal M35D, all with V-drives. While the Sail Drive powerplants can push the boats at hull speed in calm water, they lack the power to punch the boat through head seas, and we all know that when the crew gets sick of slogging to windward and the day is growing late, help from the motor gets one home faster.

Corrosion is a major concern of Sail Drive owners, though many said they’d had no problems. On this issue, owners seemed split down the middle: half said they wouldn’t buy a Sail Drive unit, half said they were much less expensive and hadn’t experienced problems.

All agree that the Sail Drive greatly enhances handling in reverse, making the boat’s movement predictable—a not inconsequential consideration when berthed in a tight marina slip.

On the flip side, V-drives make access to the stuffing box difficult. But even including conventional diesel installations, owners rated overall access to the engines somewhat difficult for certain operations.

Conclusion

The Niagara 31 and 35 are two very nice, albeit different boats. Construction quality is above average. The 31, designed by German Frers, is a quick and nimble racer/cruiser that also makes a comfortable coastal cruiser. The 35 has made successful passages to the Caribbean and South Pacific islands. She’s not large by today’s blue-water standards, but well-built and very handsome.

We’re not all that keen on balsa-cored hulls for long-range cruising, but we did not receive one complaint about delamination in the hull (a few in the deck, where it is more predictable). This, we presume, is a testament to the attention and skill of Hinterhoeller Yachts. And while we think the spade rudder and small skeg on the 31 is perfect for its application, we still wonder about the absence of a skeg on the 35. Only one owner, however, lamented this configuration, though several noted the boat’s less than steady offwind handling, which might be one of the effects.

Hinterhoeller boats have traditionally held their values well. A look at the Price History illustrates this, at least until a few years ago, when values of most boats dipped. Still, today’s prices for an early 80’s Niagara 31 (about $41,000) and 35 (about $60,000) are not too far below their original base prices.

We’d take the Niagara 31 for club racing and coastal cruising, the Niagara 35 for down island cruising. Our preference would be for the larger Westerbeke-powered models, sans Sail Drive despite the fact it handles better. The corrosion potential in saltwater would worry us.