Veteran multihull sailor Peter Hogg once said that some folks go sailing while others go anchoring, and its not just those who like to race around the buoys that smile most at Hoggs Aussie-bred wit. Fellow left-coaster and yacht designer of significant acclaim Bill Lee coined the phrase Fast is Fun-wisdom relevant to monohull and multihull sailors. So with the Americas Cup immersed in multihull-mania and brimming with a controversy over the safety implications of too much speed, we decided to take another look at performance multihulls for mainstream recreational sailors, and how one part of the marine industry is redefining the daysailer and pocket cruiser.

Photos by Ralph Naranjo except where noted

Multihulls are as much about mindset as they are about naval architecture, and advocates can be divided up into Hoggs two distinct schools of thought. At one end of the spectrum lie the performance-oriented speedsters-cats, tris, and proas that can relegate a Melges 24 to the slow lane. At the other extreme are those who love their boat as a home afloat and a stable platform thats reluctant to heel. In this look at some growing trends in the multihull marketplace, we focus on the performance side of the equation and take note of trends we noticed emerging at recent boat shows.

Amidst the gaggle of Goliath-like cruising cats that have been growing more and more apparent in anchorages and marinas around the country, were seeing an increasing number of David-like alternatives. These smaller multihulls have much higher sail-area-to-displacement ratios, and if interior volume were measured, their sail area to interior-volume ratio would be even more impressive. Contemporary amas and hulls are approaching needle-like dimensions.

These new boats behave like a water spider perched on surface tension rather than bogged down in a deep two- or three-toed footprint. They accelerate with the slightest indication of a puff, and sail efficiently throughout a much wider wind range (angle and velocity). Our guideline for entry into this grouping emphasized action over accommodation, and our comfort quotient leaned toward a Spartan minimalism. Our performance lineup is split into the latest iteration of beach-launching cats and tris, and a second fleet deemed ramp rockets or trailerable multihulls that need a boat ramp for launching and a more complex trailer and larger tow vehicle.

Dipping Into Multihulls

Those curious but unsure about a multihull commitment may want to consider a resort-based introduction that lets you sea-trial agile beach-launched multihulls and even sign up for some lessons. Those who annually escape the brutal northern winters and flock to seaside destinations in the south, or head to islands even closer to the equator, will find scores of hotels and beach concessions that rent the latest, easy-to-sail cats and tris. Warm water and 15-knot breezes will tempt even the most dyed-in-the-wool monohull sailor. And spending quality time tacking a beach cat back and forth in warm water is a great way to get the feel of what multihull sailing is all about.

Those new to multihulls, or crews composed of smaller-sized kids may want to dial back the power and the risk of capsize by picking a boat with a less-than-full hoist mainsail. On some boats, the crew can also refrain from setting or unfurling a jib to keep things sedate. Many rental boats in breezy regions can be rented with much smaller mainsails. Piling on sail area by unfurling a screacher comes later, once the basics of trimming, hiking, and steering are all under control. Skimming over warm blue-green water under sail, with each friendly puff adding instant acceleration, is an approach to sailing that many find hard to beat. Its not unusual to return from a week in the sun contemplating a trailer hitch for the SUV, and a vision of a cat or tri tagging along on weekends filled with family fun.

Design Details

Naval architects point out that righting moment, or the tendency of a sailboat to stay upright, can be increased by adding more lead ballast to the bottom of a monohulls keel, planting the crew on the windward rail, or in the case of the multihull, moving the amas (hulls) farther outboard from the centerline of the vessel.

This high level of initial stability or form stability is a key component in limiting heel in a multihull, and when the righting moment is high at very small angles of heel, the boat is said to have lots of form stability. Because of its impressive initial stability, the heeling moment generated by a multihulls sail plan has less effect upon its ability to stay upright. Lateral plane and lift is another story, and without deep daggerboards, most multihulls will not point as high as a monohull. Crews head to weather by bearing off a bit and footing faster.

Smaller cats and tris also use crew weight to augment the righting moment, and some beach-cat builders like Hobie add a streamlined float to the masthead to keep the boat from turning turtle if a capsize does occur. This is a valuable safety feature, especially for those new to the sport. Sailors who have grown up with wet pants and a love of beach-cat sailing tend to migrate toward larger trailerable, performance-oriented multihull racers and cruisers.

Our second group includes three trimarans and a proa-a fleet that exemplifies sailing fun in the fast lane and some of the challenges involved in keeping the weight low and the structure strong and stiff. But first, the boats that launched the modern-day multihull phenomena: the beach cats.

Beach Cats

For decades, Hobie has been synonymous with fun afloat and sailors who enjoy the exhilaration of skimming over bays, lakes, and near-shore ocean waters. Quick to rig, fun to sail, and modest in cost, Hobies still offer a great bang for the buck. The fun factor is high and slip fees, boatyard labor rates, and winter storage charges remain alien to owners. Today, Windrider and Weta are snapping at Hobies heels, and innovations like rotomolded polyethylene hulls, endless-line furling screachers, and carbon-fiber crossbeams and spars bolster the notion that two, or perhaps three, hulls are better than one.

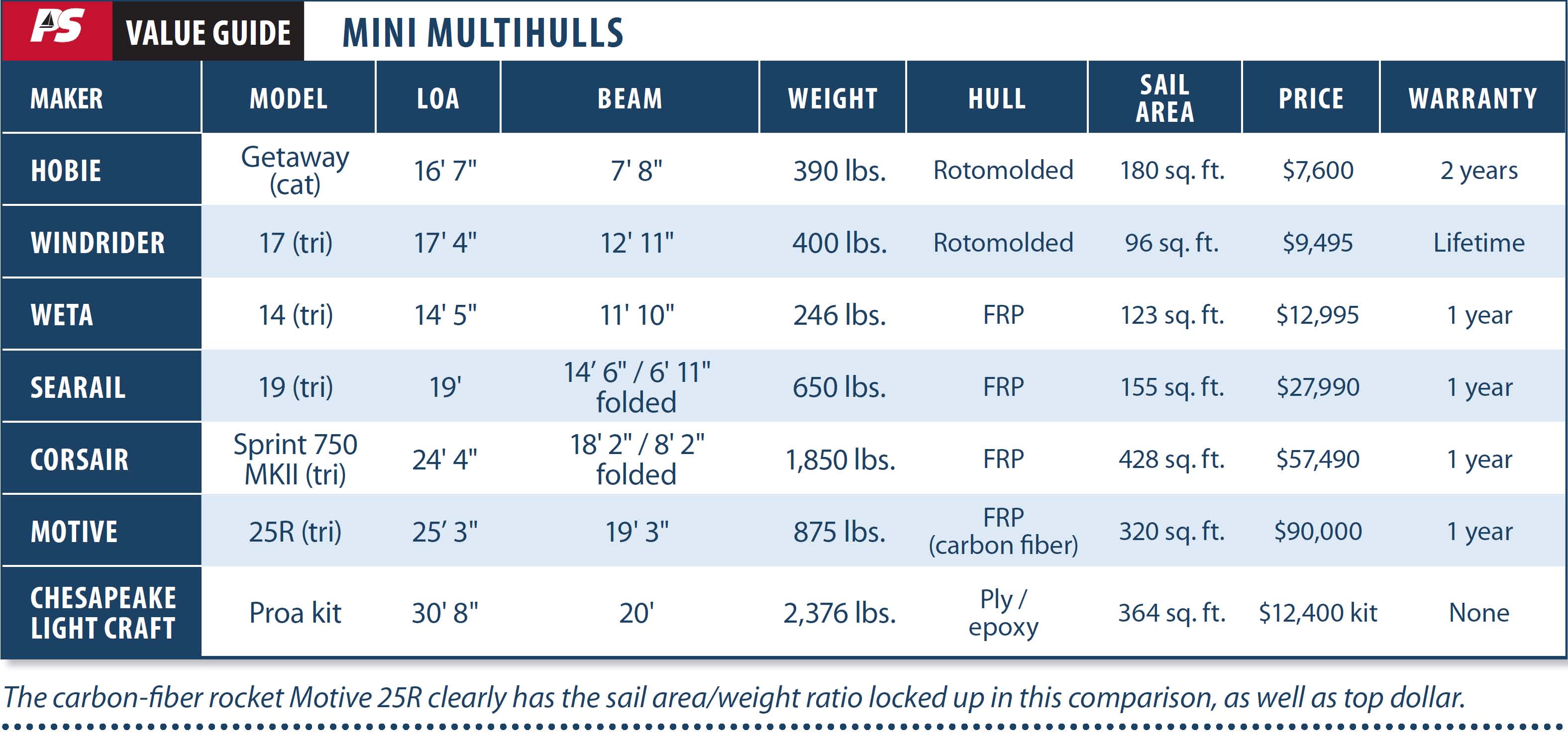

Hobie Getaway 17

Hobie continues to innovate and is putting a lot of emphasis on its line up of tough, durable, rotomolded cats that have well-engineered crossbeams, reinforced rudder attachments, and handy details that streamline the process of stepping the rig. The biggest of the companys polyethylene boats is the Getaway 17, and its sail plan (a big, boomless main and small jib) offers enough horsepower to put some spirited performance in the hands of the helmsperson. Add to this an ability to carry up to 1,000-pounds of payload, and the family fun gameplan doesn’t have to leave half the crew ashore.

Windrider 17

In May 2010, we looked at the Windrider Rave, an esoteric breed that, like the Americas Cup multihulls, rises up on foils when it reaches a certain speed. Windrider also builds a line of rotomolded beach cats. Designed by multihull pioneer Jim Brown, the easy-to-rig, easy-to-sail 17-foot Windrider emphasizes user-friendliness. The boat features two sit-in cockpit wells and foot-controlled steering. While some love this foot-pedal feature, others opt for the tiller edition on the options list.

The Windrider 17 also offers a fair amount of trampoline room to bring others along for the ride. The maximum limit on payload is 800 pounds, but as it is with all multihulls, in light air, added weight translates into a noticeable reduction in potential speed. Originally built by the rotomolded kayak company Wilderness Systems, the WindRider leveraged the companys depth of rotomolding experience. Currently built in Minneapolis, the boats carry a limited lifetime warranty and are seen in front of hotels and resorts around the world.

Weta

The lads from New Zealand saw this little gem as more of a performance-tuned mini-multi than a float for dawdling. The fiberglass amas, carbon crossbeams, mast, rudders, centerboard, and other bits and pieces follow the engineering orthodoxy that persists at the highest level of racing: Build it light, build it strong, build it stiff. With a sprit pole and endless-line furler controlling a screacher that is about the same size as the mainsail, the boat can get up and go in fairly light air, but it can also be dialed back and tamed when the crew wants to hold back on the adrenaline, or when less experienced sailors are learning the ropes.

The Kiwi designers of this three-hulled sprinter added lots of carbon fiber (spars, cross members, blades), creating a stiff, light boat with enough strength to handle a sizable sail plan. Since our initial look at the boat several years ago (PS, May 2008), a number of small but meaningful upgrades have taken place, and its this type of fine-tuning that make a good boat even better.

Ramp Rockets

The 2012 Annapolis boat show featured a foursome of nimble multihulls that run contrary to the prevailing trend toward roomy cruisers. The new, nimble SeaRail 19, Corsair Sprint 750 MKII, Motive 25R, and a 30-foot proa kit from Chesapeake Light Craft created quite a buzz.

SeaRail 19

PS Technical Editor Ralph Naranjo was windsurfing a couple of days after the Annapolis boat show and noticed that the SeaRail 19 was out for a romp. It was blowing 15 to 18 knots, and both the windsurfer and trimaran were on a full plane, sailing side-by-side at just over 20 knots. The two crew aboard the trimaran were sedately tweaking lines and carrying on a conversation, while the routine on the windsurfer was a tad more frenetic. As Naranjo put it, The SeaRail offers a civilized way to surf the bay.

Built in Vietnam, the first SeaRail 19 arrived in Annapolis a couple of days before the show. Far from sea-trialed and sorted out, the tri was up and running right after the show, and despite a small list of details that still needed tweaking, it sailed well in the breezy inshore environs of fall on Chesapeake Bay.

Principal Phil Medley, a veteran of Corsair development, has incorporated Nigel Irenss design input and plenty of his own multihull-building savvy into the new boat. The design wants to get up and go, and for a just-out-of-the-box project, there was a lot to be happy about. A little more attention to detail during construction will likely provide better finish quality. We expect that the boats arriving at this years shows will address some of the production details that still need sorting out.

Corsair Sprint 750 MKII

Corsair has been around for a while, and the level of fit and finish is clearly better than on the SeaRail. Performance is what the new Sprint 750 MKII is all about, and with newly designed amas and increased buoyancy, the boat has a greater sail-carrying capacity than the Mark I.

A large share of Corsairs success comes from the evolution and learning curve a builder goes through. The company has been around since 1984, and the theme of these high-performing pocket racer/cruisers has been continually refined. Ian Farrier-the F in the original F-series-sold the company to Corsair in the early 1980s, and in 2010, Corsair was sold to Australias Seawind Catamarans. Manufacturing has moved to Vietnam, where labor rates are low, but quality control involves ongoing training and supervision.

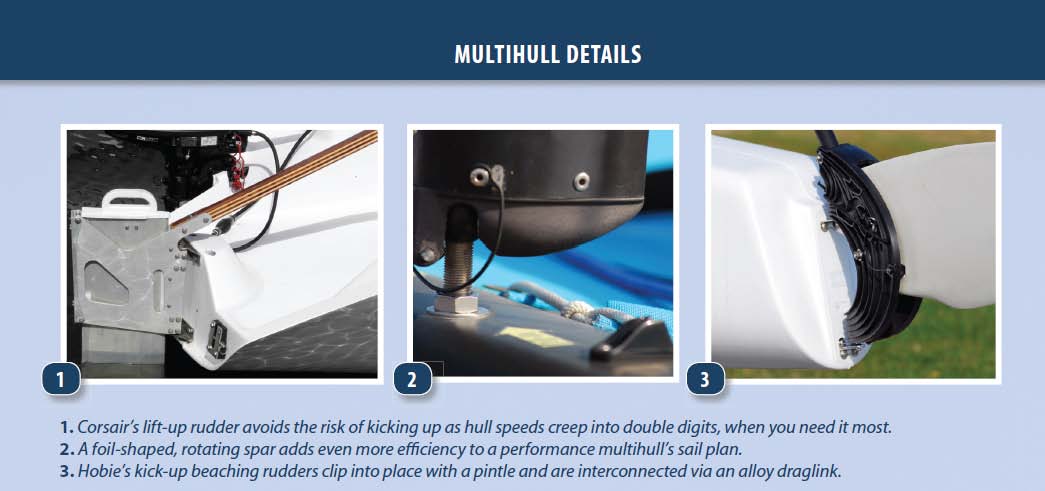

Incorporating the Farrier folding system, the new Sprint can be launched in its tucked-in configuration, and the amas quickly open up when the boat is afloat. The new Corsair blends lessons learned in earlier iterations, and the result is a well-executed racer/cruiser with good ergonomics, efficient line leads, and responsive steering-among many other performance-boosting attributes.

Motive 25R

Conceived by Pete Ansel, a former special-effects expert who has now set his sights on boatbuilding, this U.S.-designed-and-built, carbon-fiber uber-tri looks fast just sitting still. The boat is designed by New York naval architects Carl Persak and Jeremy Wurmfeld, who both do a fair share of designing super yachts. They are also accustomed to delivering cutting-edge performance-Wurmfeld designed the e33 (PS, November 2008). The two teamed up with Massachusetts Institute of Technology-educated builders Ted and Zac Warren of Salem, Mass., with a goal of tweaking maximum speed out of a very light carbon-fiber structure.

The boat drew lots of interest at the fall shows in Newport and Annapolis. Its light displacement allowed a fairly small rig and sail plan to move the agile boat efficiently, but adrenaline-seeking sailors were looking for more sail area. Its lightweight carbon structure resulted in a bit more deck flex than most sailors are accustomed to, and some additional stiffening would be easy for the builder to achieve. Testers liked how simple it was to haul the amas inboard and remove the crossbeams for trailering. A Torqeedo electric outboard (PS, January 2011) had no problem powering the boat in a flat calm at speeds up to five knots.

The Motive 25R is a floating Ferrari that will roll runabouts on Long Island Sound, and turn a good sailing breeze on Chesapeake Bay into some serious fun. Its not a daysailer for the faint of heart, and definitely not aimed at sailors on a tight budge; base price is $90,000. Expectations are high for this 25-foot, 20-knot capable speedster, and if enough boats sell to stir up some one-design racing-it will be hard to ignore.

Chesapeake Light Craft Proa

Proas are essentially a sailing canoe with an outrigger, and they require a quirky way of tacking that involves a dead stop and a maneuver that turns the stern into a bow on the new tack. This technique of flopping the boom over 180 degrees for each tack keeps the main hull perpetually to leeward, and those accustomed to the bilateral symmetry of other boats will initially be a bit flummoxed. Not only does a proa need a rudder at each end of the boat, but it also needs two headsails.

Photo courtesy of Corsair

The good news is the crossbeam architecture is not so heavily loaded because the mast steps on or in the main hull, and the single ama is always to windward. Designer John Harris has clearly been influenced by the work of Russel Brown (son of multihull guru Jim Brown), who spent a couple of decades tinkering with proa designs. These boats are fast and easily driven, and for those who find Wharram cats too roomy, preferring a backpackers streamlined approach, a proa may be just right for exploring Florida Bay, or for summer camping/cruising in the Adirondacks.

The stitch-and-glue approach is a fast and effective way to build a proa, especially if you buy the precut plywood kit and the spruce and fir lumber that lets you start putting things together according to CLCs step-by-step instructions. If you have built one of their kayaks and worked with the system, you have less to learn. In either case, boat-building is rewarding in itself; ending up with a shoal-draft cruiser that will top 10 knots makes it even easier to justify the labor.

Conclusion

We found that going fast under sail is time well spent. But it also means consequences can be more serious when things get a bit out of hand. Over the years, we have seen a number of incidents in which good boats and crews got in over their heads and bad things happened.

For example, a 15-knot romp on flat water in a steady breeze can be the epitome of sailing under control. But the same scenario transferred to a shoaling coastal region where waves stand taller, or conditions are squally, can be a different story. The same crew may find their 15-knot breeze punctuated with regular 25-knot gusts, and with each sudden puff, the odds of remaining under control begin to shift.

This is why every experienced multihull sailor develops a keen awareness for subtle changes in the weather and seaway. The net result is a hair-trigger response to gusts or wind shifts-an almost instinctual sense for when it is time to power up or dial back the energy generated by the rig and sail plan. When we finally tallied up our boat show mini-multi observations, and reminded ourselves of Practical Sailors mission, we checked off Hobies Getaway and Corsairs new Sprint 750 MKII as our practical preferences in the two categories-the Hobie as our chosen beach-launcher, the Sprint 750 MKII as our trailerable pocket-rocket.

With a little more refining, the SeaRail 19 and Motive 25R will both hold big promise. Building a 30-foot CLC proa can be both challenging and rewarding, but it is a major time commitment. The WindRider 17 may very well be the easiest multi in the grouping with which to acclimate a new crew. However, if youre possessed with an unrelenting need for speed, the Kiwi quickness built into the Weta delivers performance that we thought best delivered sit-down windsurfing.