Some say that markets afford a true test of a products value, if so, then boat shows are a great place to test the waters. Over the last two decades, in-water show attendees have noticed how catamarans and trimarans have taken over more and more slip space. Apparently, a growing number of boat buyers are convinced that two or three hulls are better than one. Skeptics still question whether this is a case of design breakthrough or more an example of a marketing success. We think its probably a good dose of each, and its time to take a close look at whats really driving this multihull mania.

Advocates tout the advantage of a lead-less approach to sailing: the boats seldom heel, wont sink, and offer a spacious deckhouse with a million-dollar view. Performance-oriented multihull fans lean toward a less voluminous approach. Their favorite ultralight designs deliver a sports cars acceleration and represent the epitome of shoal-draft cruising. Proponents remind single-hull sailors that when you put a multihull on a reach in 12 or 20 knots of breeze-all but the kite boarders and motor boaters are left astern. Despite all this keen optimism, dyed-in-the-wool monohull advocates still have a few reservations. So in Part I of our multihull report we look at the design evolution and how we arrived at where we are today.

Background

Multihull voyaging has a well-documented history that includes Polynesians traversing Oceania, Micronesians voyaging the western basin of the Pacific and Indonesians coast-hopping from Papua, New Guinea to Sumatra aboard their gossamer jukung outrigger canoes. In light air, there was always more paddling than sailing, and the risk of a squall-instigated capsize was mitigated by small sail area and inherent weakness of organic sails and coconut-fiber rigging, which, like a fuse in an electrical circuit, broke or tore before the boat could capsize.

The shoal-draft nature of these vessels favored beach launching and scooching over reef-strewn shoals. A tropical climate lessened the need forbelowdeckaccommodations and a mandate to provide shelter from hypothermia. In short, the vessel design resonated with its use.

Today, the Polynesian Voyaging Society (PVS) and the Bishop museum continue to add data and carry out valuable research. Whats clear is that the double-hull voyaging canoes of Oceania provided connectivity among the archipelagoes scattered from Easter Island to New Zealand. In full trim, these 60- to 70-foot LOA voyaging canoes displaced about 25,000 pounds and relied as much on able paddlers as they did their scan’t 500- to 600-square-foot sail plans. With a relatively small beam compared to modern multihull design standards, these 17- to 18-foot wide twin hulls did not have the righting arm of a modern catamaran. In heavy weather the spars were lowered to the deck and a basket-like drogue device could be streamed astern.

In 1975, the Society launched Hokulea-a replica of a traditional voyaging canoe. Although the FRP hulls and modern lines and sailcloth used in the replica were far from what early Polynesians worked with, the Hawaiians made up for material substitution with years worth of authentic voyaging. They replicated passages made by their forebears, and at the moment, theyre finishing up a two-year west about voyage around the world.

Herreshoffs Amaryllis

Multihulls first came to attention in North America when Nat Herreshoff designed the catamaran Amaryllis and won the New York Centennial Regatta in 1876. This began a long-standing yachting tradition of establishing rules to sideline multihulls, and effectively close the door to cats and tris.

For nearly a century there has been intense controversy over where multihulls fit in inshore and offshore racing. Fleets of one-design speedsters from Hobies to Farrier/Corsairs have had great success with their own regattas, and today theres even growing success in the effort to include multihulls in epic offshore races such as the Transpac (multihulls welcome) and the Newport to Bermuda Race (a decision is in the offing). The multihull-friendly Americas Cup, now more drag race than tactical skirmish, speaks for itself, and some of the around-the-world and trans-oceanic records have been set by multihulls.

While racers now happily claim multihulls as their own, the cruising community was where multihull acceptance first took hold. For decades, there was much more of a warm welcome for cats, tris, and even an occasional proa among coastal and ocean cruisers. It all began in a backyard experimental era that gave rise to big mistakes and great strides forward.

Arthur Piver a pilot, sailor, author and print shop owner in Mill Valley, CA probably deserves the title-patriarch of the modern multihull. He sold an idea as well as plans for his easy to build tri-hull designs. These DIY plywood boat building projects were inextricably lashed to dreams of tradewind adventures. His acolytes had a wide range of boatbuilding and seamanship skills, and not surprisingly, outcomes tended to favor better built boats and capable crews.

In Pivers wake, came some better designs and engineering. Jim Brown and Norm Cross, also west coast designers, took three hulls to the next level. Brown refined the approach to glass-over-ply construction and dubbed his slant on voyaging Seasteading. A Brit named James Wharram favored a more traditional Polynesian hull design for his DIY catamarans. They sported a short hoist, square-headed sail plan because Wharram had a penchant for favoring capsize avoidance over light-air performance.

During this era of innovation, an avid multihull aficionado once said that ferro-cement monohulls were the best thing that ever happened to multihulls! Asked for clarification, he went on to say that the appeal of boats spawned from a truck-load of wet cement drew the attention and allegiance of most of the wingnut, home-builders previously obsessed with multihulls.

With little publicity and even less marketing effort, the DIY followers of Piver, Brown, and Wharram set off in homebuilt boats headed towardfar flung points around the world. The debate over whether these multihull prototypes lived up to the pitches made by their proponents lives on, but one thing is quite clear, there were noferro-cement sailboats at any of last years boat shows, but the multihulls continue to flourish.

Backyard to Factory

Todays multihulls are a far cry from what Piver or King Kamehameha observed at Waikiki. The DIY era of the 60s gave rise to inputs from designers like John Letcher, Dick Newick, Nigel Irens, Ian Farrier and many others. Builders like Tony Smith, who started molding 26-foot Telstars in England in the early 70s and moved the company to Annapolis, Maryland where the business evolved into Gemini cruising catamarans, are emblematic of the launch of production built cats and tris. The stage was set to go global and Prout, Lagoon, Fountaine Pajot, and dozens of others set up shop.

This evolution came with taller rigs, high-modulus sail cloth and rigging to cope with more than the maximum loads generated by a vessels righting moment (righting arm x the vessels displacement). More power in the sail plan meant that when an unanticipated big gust erupts from a mediocre looking squall line, the crew had to be ready to dump the traveler and/or mainsheet, and in some cases ease jib sheets to spill more breeze.

If these steps were not taken, the heeling moment could overwhelm the righting moment and a capsize become likely. Without ballast and a low center of gravity (CG), theres very little secondary righting moment. The limit of positive stability (LPS, the point at which the boat will no longer right itself) reaches zero at around 80 degrees, having peaked somewhere between 10 to 25 degrees. In contrast, a seaworthy monohull has a much smaller righting arm and less initial stability but benefits from a secondary righting moment from the ballast. This shifts the limit of positive stability to 125 degrees or more (common for many offshore racers and cruisers).

The multihulls approach to staying upright is dominated by its beam and the buoyancy of each hull. The vessels wide stance, weight of the windward hull, and the buoyancy of the leeward hull defines its reluctance to heel. This also governs how efficiently the energy derived from the sail plan can be utilized. The advantage of this huge reluctance to heel, results in more lift and drive from a given amount of sail area. The problem with this approach to carrying sail, is that heel, a familiar warning sign of being over canvased, no longer affords an early warning.

The traditional monohull signals that a reef or two is needed when it submerges its rail or the helmsman has to fight the boats tendency to broach. The monohulls stability safety valve is its willingness to heel away and recover from a rail-plunging, boom-dragging, masthead-dunking, knockdown. But with multihulls, theres a very fine line between starting to heel and being unable to stop the rotation toward capsize.

To better understand the full implication of heeling moment, one must recognize that wind velocity increases arithmetically, but pressure on the sails increases exponentially. For example, we say that when a ten-knot breeze builds to 20 knots, the velocity has doubled. However, in the same scenario, the pressure on the sail is defined by the square of the original velocity (10 = 10 x 10 = 100). This 10-fold increase in pressure results in a huge energy transfer between sails and hull. Rig loads spike and the heeling moment increases.

At most risk are racing multihulls that have even taller rigs and greater sail area-to-displacement ratios. This makes them both faster and more vulnerable to capsize if the crew loses focus. The role of a skilled skipper and crew is paramount-at times the mainsail trimmer is the most important person on the boat. He or she becomes the failsafe when it comes to coping with the unexpected gust. And in many cases, the traveler, with its lengthy port-to-starboard, radial-shaped track is the best friend of those trying to depowering the mainsail.

Preventing capsize

One of the biggest decisions a multihull cruising sailor has to make is how much sail area to carry. The more like a race boat their cruiser becomes, the more demanding the sailing challenges become.

Normally, modern multihulls handle an average breeze with a full main and a fairly small jib (in relation to mainsail size). Its all thats needed to keep things rolling along. High-performance multihulls are so fast that the apparent wind moves forward, and even when sailing a deep reach, the breeze is on the beam and sails are trimmed to the apparent wind.

If the vessel starts to heel or bury the leeward ama, it slows down and the apparent wind velocity decreases, causing the apparent wind direction to shift aft. This causes the sail plan to be over-trimmed and increases the heeling moment, just when its least desirable. To complicate things even further, the pathway to a sheet or traveler no longer involves crossing a span of flat deck. A large, unanticipated, increase in heel can cause the crew perched on the windward ama to be more involved in holding on than reaching for the offending traveler control or sheet.

Competitive multihull crews know that they can’t weather a knock down-and so, sailing on the edge means maintaining a near-instantaneous ability to depower through the release of traveler and sheet controls. When this becomes a 24/7 obsession, one thing is certain, its no way to go cruising. This is why most cruising multihull designers have taken a different tack.

Cruising multihull designers hedge their anti-capsize bet with a less aggressive, lower sail area/displacement ratio sail plan and higher volume, increased freeboard, and more buoyant hulls. This approach works to lessen the likelihood of turning upside down, but it doesn’t make the risk completely disappear. One of the risks facing shorthanded multihull cruising stems from long night watches and the efficiency and reliability of todays autopilots.

Watch-keeping in a main saloon with 360 degree visibility meets the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGs) requirements, but it puts the person on watch too far away from the sheets and traveler and insulates them from telltale signs of changing weather. Little things like a sudden puff of cold air on a hot sticky night can signify the onslaught of a thunderstorms downburst. Its often a subtle, 30-second prelude to an approaching maelstrom, but with someone at the ready it can be time enough to ease the sheets and take over the helm.

There have been enough multihull capsizes over the last few decades to draw some formal attention. In the late 1990s, the University of Southampton, Wolfson Unit in the United Kingdom conducted a naval architecture multihull capsize study that began with a review of historical data. They compiled a series of reports on 124 capsize incidents that occurred over a 30-year period.

The study included 33 cats, 67 tris, 2 proas and 22 reports listed only as multihull. The survey indicated that catamarans incidents seem to be more wind induced while trimarans were more vulnerable to wave impacts. The tank test follow ups in Phase II were aided by Naval Architect Alex Simonis, and the study revealed some useful insights into trends and how hull shape, volume and weight affect vessel behavior. As expected, beam played a pivotal role in righting moment and lowering the vertical center of gravity (VCG) also improved the righting moment and limit of positive stability. Keels seemed to slightly increase capsize vulnerability by preventing the cat from sliding sideways when impacted by a breaking wave.

During tank testing, the center of effort (CE) of the sailplan was varied during the dynamic testing. Increasing the height of the CE correlated with increased chance of pitchpoling, so did increased displacement and moving the longitudinal center of gravity (LCG) forward. Smaller, less buoyant amas (floats) on trimarans were linked to a higher risk of capsize as were trimarans with their mass situated along the centerline of the middle hull. This early work focused on causes of capsize beyond wind heeling moments and gave designers a starting point from which to develop faster or more stable multihulls. However, designing an un-ballasted sailboat that is both fast and stable remains a challenge to be met.

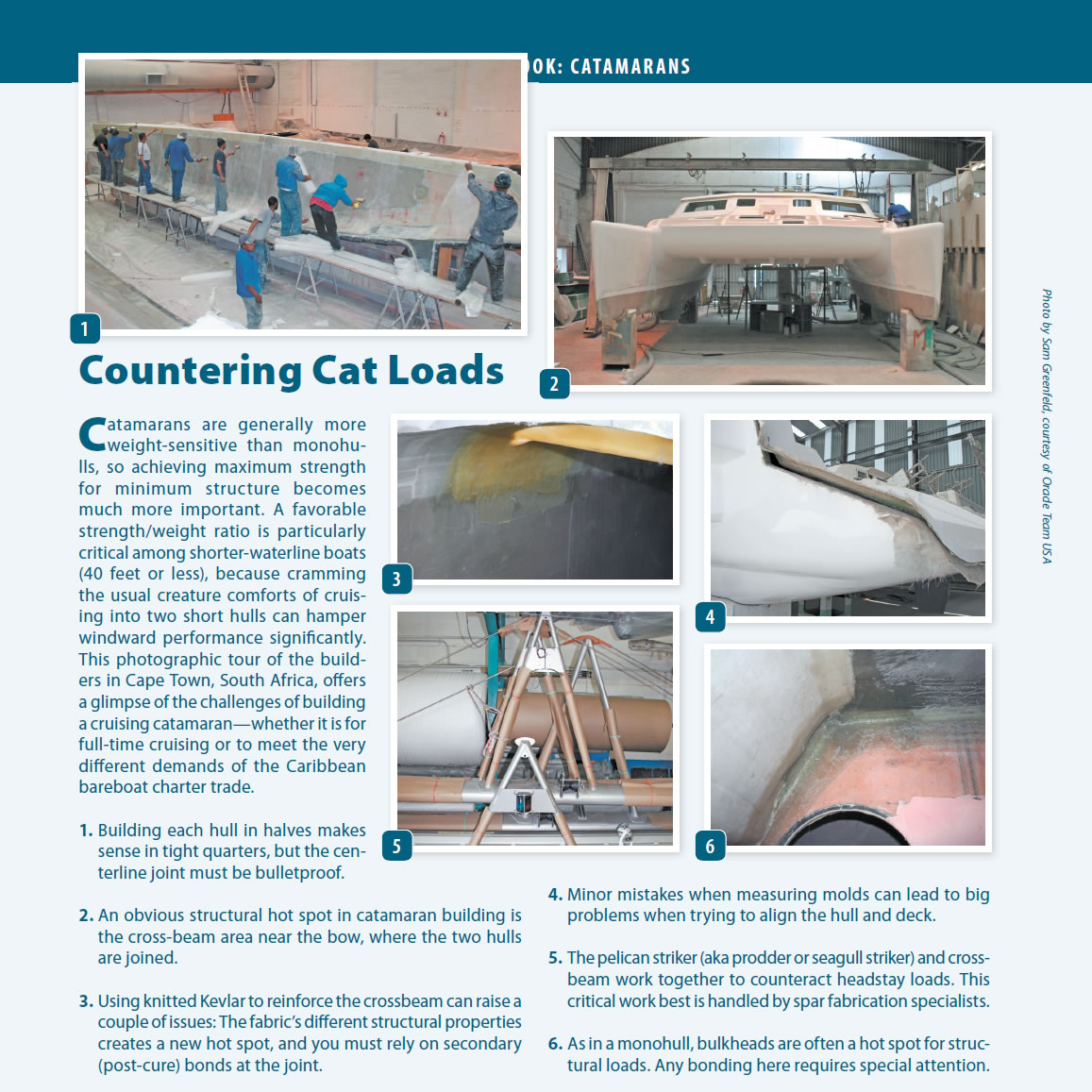

Catamarans are generally more weight-sensitive than monohulls, so achieving maximum strength for minimum structure becomes much more important. A favorable strength/weight ratio is particularly critical among shorter-waterline boats (40 feet or less), because cramming the usual creature comforts of cruising into two short hulls can hamper windward performance significantly.

This photographic tour of the builders in Cape Town, South Africa, offers a glimpse of the challenges of building a cruising catamaranwhether it is for full-time cruising or to meet the very different demands of the Caribbean bareboat charter trade.

1. Building each hull in halves makes sense in tight quarters, but the centerline joint must be bulletproof.

2. An obvious structural hot spot in catamaran building is the cross-beam area near the bow, where the two hulls are joined.

3. Using knitted Kevlar to reinforce the crossbeam can raise a couple of issues: The fabric’s different structural properties creates a new hot spot, and you must rely on secondary (post-cure) bonds at the joint.

4. Minor mistakes when measuring molds can lead to big problems when trying to align the hull and deck.

5. The pelican striker (aka prodder or seagull striker) and crossbeam work together to counteract headstay loads. This critical work best is handled by spar fabrication specialists.

6. As in a monohull, bulkheads are often a hot spot for structural loads. Any bonding here requires special attention.

A couple of comments: First, when the wind speed doubles, the force and heeling moment on the sails quadruples. It does not go up by a factor of 100. Anyone with a knowledge of aerodynamics could confirm this. Secondly, while some multis do capsize by tipping sideways, theys mostly go over because they dug a leeward bow into a wave, causing the bow to dig in and the boat to capsize diagonally. By design, this is really difficult to do with a modern cruising cat – especially on with a solid bridge deck between the bows. Finally, unless there is a really strong and sudden squall (e.g. a downdraft from a thunderstorm), there is lots of warning that a cruising multi is starting to get overpowered. While I would not say that you could not capsize a modern cruising cat, barring an unforseen thunderstorm squall, I think that you would have to work at it.

Good job. Had the same thoughts as I read the article.

Thanks Rob. It is definitely a mistake to lump all multihulls together. Here’s a related article that talks about some of the details you mention. https://www.practical-sailor.com/sailboat-reviews/multihull-capsize-risk-check

Yes.

Another point is that with experience you become very attuned to heel.

There’s a picture of my 24’ cat flying a hull a few inches above the water. I had no instruments. I’m not looking where I’m going. I remember exactly what I was thinking/doing. “This is fast enough. Dump some main”.

I was at peak righting moment.

Moving to a tri which basically isn’t sailing until it reaches several more degrees of heel beyond that level, I struggled for a few years to push the tri beyond cat levels of heel.

Monohull sailors probably react to weather helm building up. Multi sailors probably react to heel levels.

And one thing we watch for and fear is allowing ourselves to keep too much main up with the apparent aft of the beam.

all good on a 24 ft performance racing cat (here on lake Garda we’re used to maintaining a flying hull in steep short waves and blustery conditions) but there is none of that feel on 45+ foot cruising cat. no sense of tilting, sliding. listen to anyone involved in ‘cat-size’ – seasoned crews say its just boom and you’re upside down.

Thanks Mr. Nicholson for a well written article. One rarely encounters articles on the mono-v-cat debate that can avoid acrimony and hysterics. This piece was without that and much appreciated.

The credit goes to Ralph Naranjo, one of the most knowledgeable sailors I know. I’ve corrected that now. Many bylines were lost in Practical Sailor’s roll-over to a redesigned website, and I suddenly became a more prolific writer than I’d ever imagined. I try to fix the bylines as I go along, but chances are, if it has my name on it, I probably didn’t write it. But if there’s a word misspelled (no matter whose byline it is), that’s definitely me.

Increased creature comfort provided by a multihull over a monohull of the same length is the obvious choice of the coastal cruiser which is why so many yacht charter companies offer an increasing number of multihulls for charter. Yes, on a reach they go fast and hurray!, they do not heel so drinks do not spill as easily.

But for those who wish to get serious in planning a bluewater cruise or perhaps a circumnavigation, reaching the end of a passage without breakage or worse in my view is less likely with a monohull. Yes, there will always be breakages but throughout our circumnavigation, the only dismast we happened to be in radio contact with was a multihull. Certainly, a monohull is more forgiving if caught over canvassed for conditions; perhaps a squall at night. Of course a multihull is great on which to host mooring parties but a monohull is cheaper to dock. So much for discussion re pros and cons BUT there is no doubt in my mind that a monohull in the long run is safer especially for the single-hander or if crewed by a couple. Yup, ours was a 44 foot monohull. ARGONAUTA I

Having been sailing multi for 50 years, I was particularly interested in the design evolution material here. A nice summary but you missed any mention of CSK and Rudy Choy, Polynesian Concept and Sea Smoke. CSK put catamarans on the Pacific map in the ’50’s, and had some interesting challenges in getting multi into the TransPac.

As an ominous post-script….did not Cross and Piver, if not Brown too, all die on their multi-hull at sea?

Les Rose:

Arthur Piver was lost off the CA coast in a borrowed Nugget 24, his smallest “cruising” tri design. Word was it was not well built, and he was solo sailing in an area of heavy cargo ship traffic. We will never know what happened, but many think he was run down at night near PT Conception by a tanker or freighter. Cross and Brown did not die at sea so far as I know.

Back in the day, a buddy and I bought a damaged Nugget for a few hundred bucks, repaired it, and sailed it around So. Cal. waters (including to and from Catalina) with never an auxiliary engine! Seems crazy now, but we had fun, and learned a great deal about sailing and multihulls. Tris were very popular among CA surfers, who had become interested in sailing – like us. In law school, I bought (from the Sea Scouts, again for a song) and sailed a “Triumph 24” on the SF Bay and coastal waters. The Triumph was an early commercially produced, fiberglass hulled Nugget, built in Alviso in the South Bay. This one had a 5 hp Evinrude longshaft. It was a blast flying one and even, though rarely, two, hulls in high SF Bay winds – although I did once lose a mast in the slot off Treasure Island when a gust took a spreader before I could ease the main. (I bought a new, perfectly sized black AL mast as a replacement from a guy in Alameda for $95 – what a difference from today!).

A young couple near my slip in SF’s Gashouse Cove Marina, had built their Nugget and ended up doing a circumnavigation (via the Panama and Suez Canals)! It took them 2+years. As might be expected, they had amazing stories to tell. Their take was that wave action, particularly from an unexpected “rogue” type wave was the greatest capsize danger. But, they made it – although they then sold their tri and bought a live-aboard power boat.

A couple of Piver’s early books, that really helped popularize early multihulls are really worth a read, if they can be found in print: “Trans-Pacific Trimaran” about his Pacific voyage in his 36’ foot Lodestar” aft-cabin design, and “Trans-Atlantic Trimaran”, his Atlantic crossing in his 30’ “Nimble” design.

The calculation about the increase in force on the sails as the wind increases is incorrect. The force on the sail grows quadratically with the wind velocity. That means that when you double the wind velocity, the force on the sails goes up by a factor of four, not the factor of 10 claimed above.

A simple thought experiment explains this is true. The wind force comes from air molecules colliding with the sail. If you double the wind velocity two things happen. First, each air molecule that hits the sail exerts twice as much force, since it’s going twice as fast. Second, you get twice as many air molecules hitting the sail every second. The combination of those two effects causes the force to go up by a factor of four.

Also note that this is not exponential growth, which is much faster than quadratic.

Thank you Jon for further clarifying the physical explanation that an increase in speed has on wind turbulence. The quadratic relationship was already pointed out earlier in the first comment but I appreciate your more thorough explanation.

Only Piver died at sea, in a small, borrowed design of his, said to have been poorly built. Norm Cross died of old age a couple of decades ago. Last I heard, Jim Brown is still alive and living on Chesapeake Bay.

On the subject of reducing the risk for a capsize, has anyone given serious thought to how an adjustable self-release cleat for the mainsail sheet might be designed?

This exists in the UpSideUp system from Ocean Data Systems. Just sailed a performance cruising cat with the system installed and it is reassuring to know the system is there when you are on watch at 3am with no moon and squalls in the area…even with appropriate reefs already taken.

Hi Chris, thank you very much for the tip on the UpsideUp system! I looked at their web links, and as I expected, it’s based on all-electronic servo units.

I have been giving some thought towards a mechanical system for a life preserver D ring actuated trip line to adapt to a windvane self-steer for a man-overboard situation. But obviously, connecting a tethered cleated sheet release mechanism to the D ring of a helmsman’s off-balance body weight would very likely be too late to prevent a multihull capsize in most conditions.

But, at any rate I’m going to contact Ocean Data for more info and see if their pricing might be within most cruising budgets. Ocean Data seems to imply that their basic model releases a sheet at a preset degree of incline. Do you know if that is a user preset?…or is it a factory preset?

Steve Gross:

Well, Arthur Piver, ever the creative DIY innovater when it came to multi hulls, had just such a thing. Crude by todays standards; but it actually worked – at least some of the time. It’s been many years, but, as I recall, The main sheet was led along the cabin top through a block and an eye/fairlead to a cam cleat bolted to a 3/4” thick square block of wood about 8” X 6”. That was hinge bolted to a similar block, that held the fairlead. The fairlead block was bolted to the cabin top, near the aft edge so that the 2nd block with the cam was over the rear cabin edge, at a 90 degree angle down. A bungee cord was bolted to the lower portion of that block, and extended straight down to another cam cleat. The bungee held the block with cam cleat and main sheet in position. But, if enough strain was put on the sheet, via wind pressure on the main, the bungee would release the hinged block, which would rotate up, releasing the sheet from its cam, releasing the main. One could even adjust the release tension by the size and stretch of the bungee! Rube Goldberg would have been proud – but the concept was actually pretty sound. All bolts, of course, were through bolts.

An interesting point made in another sailing forum was that an inevitable consequence of the proliferation of cruising catamarans is they occupy two slips where a mono only requires one. As slip availability shrinks worldwide, the growth of catamaran ownership is a double whammy.

I loved my Gemini 105 cat. Shoal draught, drying out etc and Padstow to Cardiff on the end of an ebb and a flood. But once I found I was more and more single-handing I went back to a monohull, (Westerly Ketch). Slower but no worries, able to cook, etc without any worries. If overpressed it may tip a bit, start luffing up etc but wont do anything nasty. The only thing that would capsize it would be a broach and a following breaking sea, those conditions shouldn’t come on suddenly.

The new breed of super-fast tris like the Dragonfly and Rapido seem to be getting closer to wrapping many of the advantages of mono’s (folding amas for narrow slips and more mono-hull like sailing ) as well as the flat and shallow draft sailing of cats…..

Thanks for a great article, and for your readers’ erudite comments.

I bought a Farrier F33XC five years ago. Wanted something like my Wayfarer Dinghy to cruise, but with room for a wife and three kids. With regards to creature comforts, we’re definitely “camping” relative to similar length monohulls, but we are sailing when most are motoring, and the room on deck makes up for the cramped space below. My motto: If you want the comforts of home, stay home.

I cruise in British Columbia, where summer winds are notoriously light. To paraphrase Conrad, when it does blow, I reef early – ’cause any damn fool can carry too much sail.

And yes, now that it’s been mentioned, I’ve learned that angle of heel rather than weather helm that indicates a sail change is in order.

With regards to permanent moorage, I’ve been lucky to find a fabulous spot (close to the San Juans and the Gulf Islands) heavily discounted because it’s almost dry at low tide. The spot is discounted because it’s useless for most boats, but perfect for mine!

It would be better to have an article about multihulls written by someone like Drew Frye, not by a “dyed-in-the-wool monohull advocate”. He would have chosen a less inflammatory title, recognizing that sailors choose different types of boats for a whole range of reasons.

Let me first qualify that my sailing experience includes a lot of racing one designs like Lasers, Finns, Thistles, Lightnings, Snipes, sailboards, beach cats, Tornado catamaran, A-Class catamaran, and Weta trimaran over a +50 year sailing journey. I’ve also had the opportunity to race on several Gunboat catamarans and currently own a J/80 in my stable of boats that we race locally.

Agree with Richard on how the multihull community is sometimes viewed by the monohull community. Sailing World did an article several years ago about the A-Class catamaran and used the term “speed freaks” in their article to describe the sailors when the reality is that the class is populated by mostly over 45 year old former dinghy and keelboat sailors.

When we bought our Corsair Sprint 750 and wanted to race it locally, the PHRF powers at be told me that the boat was too dangerous around monohulls because it could not sail upwind, could not tack, and was too easy to capsize. This all opined by individuals who had never sailed a catamaran or a trimaran. After many instances where we totally disproved their assertions, they still stuck to them!

Multihull technology continues to evolve as performance gets better, so does safety. We recently upgraded from the Sprint 750 to a Dragonfly 32 that my wife and I will primarily cruise but also do some local distance races. It’s a powerful boat but incredibly well mannered and a joy to sail. Out of over a thousand Dragonflys built since the early 90’s, there have been fewer than five documented capsizes and all happened while racing when the crew made the choice to carry too much sail area in high winds and were pushing too hard. No one hurt or lost and boats all recovered in each instance. There have been no capsizes of Dragonfly tri’s doing what they are intended for which is performance cruising.

There’s a lot of tit for tat in comparing monohull to multihull choices. As Richard states, you have a lot of factors to consider when determining what would work best for you if looking at both options.

That’s a pretty nasty comment there “Dick”.

I realize that this is not intended to be a comprehensive history of multi-hulls but it still feels remiss to not mention the now stratospheric prices for well built 40’+ multihulls. My son wanted to take his family cruising a few years ago and bought into the multihull mania. He sold his house and wound up spending three times as much money on a 46′ Leopard as he would have needed to for a comparable length monohull. By the time he was done fitting out in Florida, he had burned through his cruising money. Also Covid happened and island hopping in the Caribbean became totally chaotic. Long story short is they never made it to the South Pacific and now live in the mountains of Idaho! If they had bought a 50′ monohull on the West coast for 1/3rd the price, they would be cruising French Polynesia today…

The article also failed to mention the limited number of multihull slips, at least in Florida, and the exorbitant prices charged for the few that do exist.

A long, long time ago I was a fan of Jim Brown’s, ‘The Case for the Cruising Trimaran’, as it seemed to offer to bring a cruising boat into a price bracket that a young scuba instructor might possibly be able to afford to buy or build.

Now that I am no longer young, no longer impoverished and no longer infatuated with cruising the tropics, I am modifying a (monohull) motorsailer for cruising the Inside Passage to Alaska. Definitely a move in the direction of “practical sailing”! For the North Pacific, to me that means inside steering, diesel heat, radar, anchor windlass and a way to store a 10′ rigid dinghy on deck.

Pretty disappointed to read a one eye view of catamarans stating 1990 stats on safety.

As with any cruising sailer, you plan for the weather and trim accordingly to the conditions. Can you please supply up to date statistics for cats that have been capsized and the amount of mono hulls that have sustained damage from being knocked down?

How can the average person afford the high price of a catamaran, the rapidly increasing price and unavailability of two slips, coupled with the exorbitant ripoffs of boat yard maintenance? Its almost impossible! Buy secondhand, fix yourself, sail and sell!

Same old argument[s], I see nothing new. Read as much information as you can find, allow for biased interests and opinions, take your choice according to your needs and experience, pay up and go sailing. BUT I’m finding it increasingly difficult to read the Amerenglish used in this magazine’s articles, because poor punctuation and word order distract me from the content. For the record : There exists a perfectly serviceable semi-colon [;], please learn and use it. The – should be used only for joining closely-related [see ?] words. That idiotic long ‘dash’ should never be used. Inserting adverbs into the middles of verbs is a nasty American habit which is beginning to infect less well educated English English. Finally, there’s an apostrophe [‘] which should be used to indicate either possession or an omitted letter [there is, see ?] and not to indicate a plural. Otherwise, usual thanks for an amusing article. I doubt that it will alter many opinions ! Rob Neal.

Perhaps you would be better served by reading one of the oh-so-many (see how i used a single dash there?) publications that are written in the Queen’s (or is it King’s now?) English which provides the same value and information as our near-illiterate, rebellious (and victorious, might I add) magazines.

Or perhaps it might be better to overlook dialectical differences and focus on the substance of the discussion. Address that or please keep your pedantic opinions to yourself.

To add to Rob’s scathing criticism of the many typos and occasional errors in grammar that PS readers have still to put up with, I wonder how many of us could find the time and the capacity for reliable proof reading within the need to trim the length of articles to fit within a limited availability of column inches without sacrificing the veracity of critical content, avoid one too many page jumps to complete an article, maintain graphic appeal, avoid ever present potential for litigation, meet deadline commitments for publishing, and plan for sufficiently interesting future topics, all within subscription revenue projections and non-existent revenue from non-existent advertisers, and still find time to go selling. Phew, that was a mouthful, … and only one typo!