There is no doubt about the Deerfoot 61’s purpose in life. This boat is made for longdistance cruising. “We’d sailed thousands of miles on a 50′ foot CCA-designed ketch and like most liveaboards we dreamed of the perfect yacht,” says Steve Dashew, author of the Offshore Cruising Encyclopedia. “We never realized this dream would end in a boatbuilding business.”

Dashew built the first Deerfoot, a 68-footer, in New Zealand in 1980. Subsequently, several more Deerfoots, including one for himself, were built in New Zealand and South Africa. “We soon found there was a void in the sailboat market for efficient sailing vessels designed not by the illogical biases of a racing rule, or by concepts thought up by marketing experts,” said Dashew.

Since 1980, 16 Deerfoots, ranging in size from 58 to 74 feet have been built. “Four of our fiberglass boats have been built at Scandi Yachts in Finland because they do the best fiberglass work,” says naval architect Ulf Rogeberg who worked with the Dashews to create the Deerfoot designs. “The aluminum boats have been built at Walsted’s in Denmark.”

In 1986, the Dashews, overwhelmed by the size of the Deerfoot project, sold the business to Jim Jackson and Christine Jurzykowski, owners of the 74′ aluminum Deerfoot ketch, Maya. Jackson, president and executive director of Fossil Rim Wildlife Center, a 2,900-acre wildlife reserve in Glen Rose, Texas, continues to build Deerfoots in the Dashew tradition. Building headquarters have recently moved from New Zealand to Able Marine Inc. in Trenton, Maine.

The Concept

The Deerfoot concept is based on three principles: efficiency, safety, and comfort. “The key is to have a hull which allows you a nice interior while carrying the weight of the boat in the most efficient manner,” says Dashew.

Ulf Rogeberg, who previously worked with Paul Elvstrom in Denmark designing 12-meters, explains: “We have tried to create a canoe-shaped hull that is easily driven, a hull with a fine entry angle, narrow waterlines and easy bilges. We have further tried to distribute volume so that the longitudinal center of buoyancy does not move aft when the boat heels. If a boat heels over symmetrically, if its stern doesn’t kick up and the bow doesn’t bury itself, you’ll have better stability, steering control, and performance downwind.”

A fine entry angle and a long, narrow hull also reduce drag and provide comfort and efficiency upwind and reaching. With an easily-driven hull, the Deerfoot’s rig can be substantially shorter than is needed on a beamy boat with a short waterline. A smaller rig means more stability, less sail changing, less work for a shorthanded crew, and a more comfortable ride.

How does the long, narrow hull affect the interior? While short, fat boats have their beam concentrated amidships, the Deerfoot’s relatively narrow beam is carried further forward and aft. This means there’s a lot of storage space in the bow and stern. Amidships, the Deerfoot appears spacious because there are few bulkheads, and ceilings are kept void of bookshelves or lockers.

Construction

The Deerfoot’s hull, deck and bulkheads are a fiberglass laminate cored with one inch Baltek end-grain balsa. The laminate schedule is unidirectional roving and mat laid up with vinylester resin to resist osmotic blistering. Although balsa is a strong, light core material, a completely water-resistant composite core like Airex seems preferable.

Reinforced with two longitudinal stringers and 13 athwartships stringers made of fiberglass, the hull is strong. There’s also extra fiberglass around the mast, and at the turn of the bilge and bow area in case of a collision. The hull-to-deck joint is an inward-turning hull flange overlapped by the bulwark flange. The joint is through-bolted, coated with fiberglass and topped with a teak toerail.

The Deerfoot 61 keel, a NAACA foil fin, is a steel weldment with lead ballast encapsulated at the base. Above the ballast compartment, the keel is divided into three tanks—two for water (140 gallons) and one for fuel (160 gallons). A sump (with bilge pump) divides the water and fuel tanks. Both fuel and water tanks are fitted with Tank Tender pressure gauges for sounding the tanks. The water tanks have an inspection plate on the outside of the keel.

Storing fuel and water in the keel has a number of advantages. First, it gives the Deerfoot 61 a moderately high ballast ratio (about a third of the Deerfoot’s weight is in the keel). This lowers the center of gravity and improves stability and windward performance. It also means you have more storage space under seats and bunks. On the down side, there is no way to inspect the tanks from inside the hull, and the water and fuel supply could be jeopardized if your keel is damaged.

Made of aluminum with a six-inch diameter aluminum rudder stock, the Deerfoot’s oversized spade rudder improves steering efficiency and windward performance. However, hanging an aluminum rudder behind a steel keel could result in electrolysis. A fiberglass rudder with stainless steel shaft might be a better choice. You also cannot apply copper bottom paints to aluminum and the proximity of the aluminum rudder and stock to a copper painted bottom could cause corrosion problems.

The mast is stepped on two aluminum plates that are bolted to a fiberglass mount. The steel keel further supports the mast step.

Stainless steel straps form the chainplates, which extend through the deck and bolt to fiberglass knees. In the photos we looked at, the chainplate installation looked strong. However, with the help of two boatbuilders at Able Marine, we unsuccessfully tried to uncover the chainplates by dismantling the interior. Ulf Rogeberg admits getting to the chainplates is “tricky.” It might be less so if Deerfoot shortened the valances or bookshelf fiddles running behind the settees.

Seacocks are Marelon. Some people prefer bronze seacocks with bolted flanges (we have had reports of handles breaking off Marelon seacocks), but on a boat with a steel keel and aluminum rudder, Marelon is probably a good idea.

You’ll be hard pressed to sink a Deerfoot. The 61 has three watertight bulkheads. One separates the forepeak from the living area, and one separates the living area from the engine room. Each watertight area has its own bilge pump. The bilge pump in the forepeak doubles as a deck wash down pump. There’s also a large Edson manual bilge pump mounted in the bilge near the mast.

The 14-foot forepeak, a huge storage area, is a cruising sailor’s dream. It has sail bins, anchor bins, and pipes for tying dock lines and sheets. There’s also room for fenders and the other paraphenalia that usually collects on deck.

There’s a “garage” aft (behind the engine room) for storing propane tanks, outboard motors, and diving tanks. It’s also a good place to keep the liferaft where it can be deployed easily if the need arises. The “back porch”, a small “sugar scoop” behind the “garage,” has a fresh water deck shower, and a stern ladder to make climbing aboard easy. On a boat with such high freeboard, this arrangement could be a real lifesaver if a crewmember were to fall overboard. For everyday use, the fold-up ladder is a bit lethal, however, since the bottom half hinges up but doesn’t lock in place. The unwary visitor may reach for a rung and end up in the drink.

Rig

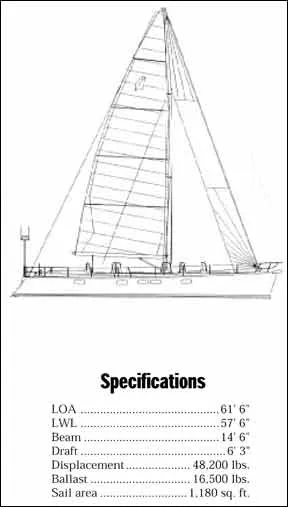

With a 65 foot mast and a working sail area of just 1,150 square feet, the Deerfoot 61 has an efficient, easily-handled cutter rig. Double swept-back spreaders and oversized Navtec 316 stainless steel wire rigging with Norseman terminals provide support for the tapered aluminum spar which has a fair amount of induced bend.

Hydraulics control the permanent double backstays, the boom vang and the inner forestay. The backstays work in tandem to keep the headstay tight for best upwind performance. The hydraulic inner forestay when tightened bends the mast moderately to flatten the mainsail. It can also be removed to facilitate tacking the jib.

Performance Under Sail

The Deerfoot 61, with its narrow, easily-driven canoe shape, fin keel/spade rudder and moderatesized rig, is a fast passagemaker. Deerfoot claims that one of their 61s averaged 209 miles a day from New Zealand to the Panama Canal. They also claim another averaged 11 knots in 25-knot winds on a broad reach from Marblehead to the Cape Cod Canal. Even if you subtract a few knots (or miles) from these averages, that’s still fair sailing.

We sailed the Deerfoot 61 from Newport to the boat show in Annapolis in October, but our story was different. It was a beat to windward the entire way. In light to moderate winds the boat still averaged seven to eight knots. In 35-knot winds encountered off Delaware Bay, the boat handled well, but pounded in steep, short confused seas.

In most conditions, the 61 is so well balanced that you can steer it with two fingers. There’s no weather or lee helm, and you have the feeling you’re sailing a racing boat rather than a cruising boat designed for safe, comfortable passagemaking.

In keeping with the philosophy that a cruising boat should be easily handled by two people, the Deerfoot 61’s working sails are small. Upwind, the Deerfoot is designed to sail with a jib that just overlaps the shrouds. For light air, there’s a reacher that’s set on its own stay four feet forward of the headstay and a 1.5 ounce 85% spinnaker for downwind.

Performance Under Power

“Probably 99 percent of maintenance is accessibility,” says Steve Dashew. With this in mind, the Deerfoot’s large engine room has been designed with attention to detail.

Located aft behind its own watertight bulkhead and entered through either of two cockpit lockers, it houses a four-cylinder 77 hp turbo-charged Yanmar with a 3.2/1 Hurth transmission. There’s also an auxiliary two-cylinder, 18 hp Yanmar power plant mounted just starboard of the main engine.

Two 135-amp alternators (one on the larger Yanmar, one on the auxiliary) charge a 600-amp 24-volt Sonnenschein Prevailer Dryfit battery system. A 55-amp alternator (main engine) and a 35-amp alternator (auxiliary engine) charge a second 12-volt system. The 12-volt system is used to start the engines and power some of the navigation equipment. Everything else runs off 24-volt. (The 110-volt AC loads run off an inverter system.)

While 24 volts is good for handling big current draws like an electric windlass or power winches, it’s a nuisance when it’s necessary to replace equipment in countries where most everything is 12 volt. (For example, 24-volt equipment is quite common in Europe, but usually must be custom ordered in the U.S. or Caribbean.)

All 24/12 volt DC and AC cabling is laid down in PVC conduits. Wiring is marine grade and tagged with numbers at each end, but the color coding is predominantly be a vast improvement.

Belted onto the engine is a damage control pump (100 gpm) plumbed into the three watertight areas of the boat, and a Sea Recovery watermaker that desalinates 25 gallons of water per hour. The engine room also contains a large hot water heater, two toolboxes, a work bench with sink, and racks for pressure pumps and compressors. There’s plenty of work space around the engines, but the watertight bulkhead makes getting to the front of the engine to tighten belts difficult.

At 3,000 RPM the Deerfoot goes eight knots in flat seas. However, the Yanmar runs more efficiently at 2,300 RPM, driving the boat at seven knots in smooth water. Cruising range under power is about 1,100 miles.

Due to hull shape, a 26″ three-bladed Max prop, and an extra large rudder, the Deerfoot 61 is extremely handy under power—so handy that it can almost turn (180°) within its own length. The boat handles particularly well in reverse so you’re apt to feel smug when docking stern to.

On Deck

The cockpit is in keeping with the Deerfoot philosophy—comfortable for two, a bit cozy for four, but efficient and safe for shorthanded passagemaking. The cockpit drains are huge, four-inch in diameter, and there are two smaller deck drains all the way aft.

The dodger is well made with two opening windows forward for ventilation in warm weather. With forward and side windows closed, it provides a snug, dry place in inclement weather. The trade-off is it hampers visibility for the helmsman.

Two cockpit chairs, one port and one starboard, sit in wells behind the wheel. If you are tall, you can sit comfortably in either with feet planted firmly on the cockpit sole; a shorter person’s feet dangle unless you pivot sideways. (In a knockdown the helmsman may go flying since the chairs are not pinned into their sockets.)

The mainsail halyard, main traveler controls and mainsail reefing lines are lead aft to the forward end of the cockpit. However, you must still walk forward to hook the cringle to the reefing hook on the gooseneck. Headsail halyards are located on the main mast along with spinnaker pole controls.

Harken roller furling comes standard on the headstay, although you can opt for jib hanks if you prefer. The cutter stay is left bare for hank-on storm sails.

The Deerfoot 61’s long, sleek flush deck provides a stable sailing platform. There are inboard sheeting tracks for the staysail or working jib, and an outboard “T” track bolted to the top of the toe rail from the mast all the way aft for sheeting reachers, spinnakers, and genoas.

Lifeline stanchions, 1 1/4 inch in diameter and 30 inches tall, provide the extra security one needs in an offshore passagemaker. Double lifelines become triple lifelines forward of the mast to help keep crew and sails on board. The stainless steel pushpit extends around the cockpit as far as the second stanchion for extra safety aft.

The 61 comes standard with a Lewmar windlass, and the anchor chain self stows neatly into a large anchor chain bin located directly beneath the winch. Because the forestay is located four feet aft of the bow, there’s a lot of room to handle the anchor.

Seven Bomar hatches and eight dorades provide ventilation below. Stainless steel guards around the dorades prevent jib sheets from fouling and furnish handholds for crewmembers moving forward or aft.

The Deerfoot we sailed was missing some mooring cleats aft and amidships. Also, cleats and winches, though mounted with through bolts and washers into a thick section of fiberglass, have no backing plates to distribute the load.

Interior

Despite its comparatively narrow beam (14 1/2 feet), the Deerfoot’s interior is well designed for living aboard in port or offshore. Emphasis is on having an airy, open saloon. Large hull portholes and lightcolored, vinyl-covered bulkheads and ceilings create a feeling of light and space. Plush leather settees and a horizontal teak veneer enhance this feeling and give the boat a Scandinavian flair.

Stepping below from the cockpit, there are two guest cabins—one with bunk beds to port and one with a small double to starboard. When cruising, either cabin provides a good place for children or guests. The port cabin, within earshot of the person on deck, is preferable offshore.

The owner’s double stateroom forward is designed for sleeping in harbor. You can hear the anchor chain if it drags, and there’s good ventilation. This stateroom has oodles of storage and a spacious head forward with sit-down shower, large mirror, and sink.

Aft is another head with shower, stacked washer and dryer, and large linen closet. The shower compartment has big hooks inside for hanging wet towels and foul weather gear. Both heads, sprayed glossy white, are bright and easy to clean.

The long secure passageway between the companionway ladder and saloon is a good place to don your harness or foul weather gear. It also leads you to the galley to port and nav section starboard.

The nav section/office is C-shaped with plenty of room for charts, instruments and electronics. There are two tables and a rotating chair so you can sit forward or aft. (However, there’s no space for knees when swiveling the chair outboard.)

Nav lockers along the hull with roll-top lids furnish a nifty way to store books, cassettes, or extra electronics. There’s more room for a computer and other equipment on the desk mounted aft.

Across from the nav section, the galley is a typical U-shape with the stove mounted on the aft bulkhead. Counter tops are Corian which can be lightly sanded if scuffed or scraped. There is handsome stowage for dishes and dry goods in lockers above the stove and along the hull.

Two nine-inch deep stainless steel sinks sit outboard and drain via an electric pump to a thru-hull in the aft head. They would drain more efficiently if they were installed near the centerline and plumbed directly overboard.

Hot and cold pressure water are standard, but surprisingly there are no manual salt water pumps, and only one manual fresh water foot pump underneath the galley sink.

There’s an eight-cubic-foot fridge and and a fivecubic-foot freezer across from the stove. The fridge stays cold, but its “side opening” door could be better insulated. There’s a microwave and more food lockers along the companionway starboard.

The galley and nav section look out over the saloon. There’s a large L-shaped dinette to port and a straight settee to starboard. Fiddles for bookshelves mounted behind the settees are inadequately designed for sailing offshore.

To minimize weight above the waterline, the cabin sole and furniture are constructed of teak plywood on a foam core. A good latch-down system secures the sole. However, on the boat we sailed, the cabin sole was divided into five and seven foot lengths which were much too cumbersome.

Lighting on the Deerfoot 61 is excellent. Overhead lights are round recessed halogens and large rectangular flourescents. The saloon has strip lights behind the valances and in the kickspace along the cabin sole. Small reading lights are mounted above bunks and settees.

Large hatches, which provide plenty of light, are fitted with storm cover tracks so they can be left cracked in inclement weather. They also come with an innovative system of bug and sun screens which conveniently slide in and out of the deck.

Conclusion

The Deerfoot 61 is a luxurious boat. It’s also a sensible, liveaboard boat that offers outstanding accommodations, superb craftsmanship, and unparalleled performance. It’s obvious that Dashew and Rogeberg put a lifetime of ocean voyaging and boatbuilding experience into the Deerfoot design.

All this comes at a price, of course. New, a coastal cruising version of the Deerfoot 61 runs $680,000, add another $120,000 for the offshore package, which comes with sails, two autopilots, watermaker, refrigerator-freezer, ground tackle, and electronics.

This is a lot to pay for any boat, but you’ll get top quality for your dollar.

Several years ago I saw one of these boats in Wellington New Zealand. If I had just won Lotto I would have made the owner an offer he could not refuse!! Great review.

You gave a thorough and thoughtful review but you incorrectly used the term ‘electrolysis’ instead of the proper term electrolytic corrosion. Btw, electrolysis is a process of removing hair, so I don’t think you meant that.

I have sailed aboard the Deerfoot 72, Locura. It’s a fabulously fast boat and the quality is evident the moment you step aboard. It’s for sale now and sure wish I could make an offer on it.

Excellent Write up

A very informative review. I do find a few of your criticisms both valid and surprising at this level, however. Balsa core may have been the go-to core 40-50 years ago, but as any C&C owner can tell you, leaves much to be desired in any environment where freeze-thaw cycles may occur. I also did not read, or may have missed, the partial solution in which encapsulated plywood or fibreglassed in pads isolate the balsa in areas where through-bolted gear is found on deck. Related is the mention of the absence of backing plates and the possibility that flexing might unbed or otherwise allow water into that balsa core. Also concerning are the dissimilar metals in the rudder; I agree with you that a different approach would be preferable.

Other than these cavils, Deerfoots sound very well thought out and it was nice to have an “under the hatches” walkthrough. I always learn something I can use on our less pretty ocean cruiser

Good thorough review. I enjoy Nicholson’s approach and his comments. I am looking forward to more thorough analyses of cruising sailboats.

Good review of the Dashew philosophy and the 61 and have been a follower since the late 1980s. I only wish we could see some of it applied to more boats in the 40-50ft range.