Thunderbird, a Cal 40 owned by IBM president T. Vincent Learson, took first in fleet over 167 boats in the 1966 Bermuda Race. Because this was the first computer-scored Bermuda Race, Learson got a lot of gaff about the IBM computer that had declared him the winner—and about beating out his boss. Thomas J. Watson, IBM’s chairman of the board, sailed his 58′ cutter, Palawan, second across the line, but ended with second in class, 24th in fleet, on corrected time.

In fact, the computer scoring system was not especially kind to Learson. Both he and Watson would have fared considerably better under the old system that calculated scores from the NAYRU time allowance tables. Thunderbird’s victory was a legitimate win, another in a stunning series by Cal 40s that was establishing the boat as a revolutionary design. The first Cal 40 was built for George Griffith in 1963. That winter, hull #2, Conquistador, took overall honors in the 1964 Southern Ocean Racing Circuit (SORC). The Transpac races of 1965, ’66, and ’67 all went to Cal 40s. Ted Turner’s Cal 40, Vamp X, took first place in the 1966 SORC. In the ’66 Bermuda Race, five of Thunderbird’s sisterships finished with her in the top 20 in fleet, taking five of the first 15, four of the first nine places. And so on. In their first few years on the water, Cal 40s chalked up an astonishing record.

The 40 was the fifth in a line of Cal designs that C. William Lapworth did for Jensen Marine of Costa Mesa, California. Lapworth had already designed a series of moderately successful racing boats, the L classes, including an L-24, L-36, L-40 and L-50, when he teamed up with Jack Jensen. The Cal designs were built on concepts he had tried in his Lclass boats. The first Cal was the 24, Jensen’s first boat, launched in 1959. The Lapworth-Jensen team then produced a 20, 30, and 28 before getting to the Cal 40, which proved to be a successful distillation of Lapworth’s thinking up to that time.

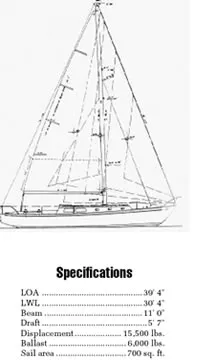

Aspects of the boat that departed from the conventional wisdom were her light displacement, long waterline, flat bilges to encourage surfing, fin keel and spade rudder. The masthead rig is stayed by shrouds secured to chainplates set inboard of the toerail, a then unusual innovation that allows a reduced sheeting angle. The success of the design helped legitimize fiberglass as a hull material, establish Jensen Marine as a significant builder of fiberglass boats, and propel Lapworth to the forefront of yacht design.

Three decades have passed since Lapworth drew the Cal 40. In that time, using computers to score races has become commonplace—boat measurers and designers would be paralyzed without them. The CCA Rule, the NAYRU tables and the Portsmouth Yardstick have been replaced by IMS, IOR, and PHRF, with the effects of their parameters expressed in the shape, size and weight of new boats. New building materials and techniques have changed the meaning of terms such as “light displacement,” “long waterline,” “fin keel,” and “fast sailboat.” Today the Cal 40 is a dated design, having been surpassed in her revolutionary features by her descendents. She remains among the esteemed elite of racing yachts, but she is not especially light, long on the waterline, or fast compared to current designs.

The Cal’s builder was transformed by time, as well. Jensen Marine was bought by Bangor Punta Marine, and the Cal production line was moved to Florida about the time that the Cal 40 went out of production in 1972. For the next decade, the company’s name and address shifted between combinations of Cal, Bangor Punta and Jensen in California, New Jersey and finally Massachusetts, where it joined O’Day under Bangor Punta’s umbrella in the early 1980s. After 1984 the company was called Lear Siegler Marine, Starcraft Sailboat Products, and finally emerged as Cal, a Division of the O’Day Corporation, in Fall River, Mass. Cal and O’Day ceased production in April, 1989.

Construction

The construction of the Cal 40 is typical of Jensen Marine boats of the 1960s. The hull is solid hand laid fiberglass with wooden bulkheads and interior structures. Strips of fiberglass cloth and resin secure the wooden structures to the hull, but this tabbing is rather lightweight and has been reinforced in some Cal 40s where it has failed. If it has not been reinforced, it probably needs it.

Because saving weight was a priority in building the Cal 40, the reinforcement provided by the bulkheads and furniture is critical to hull stiffness. Failure of the bonding can be a significant structural concern.

The hull-to-deck joint is an inward-turning hull flange, upon which the deck molding is bonded, then through-bolted and capped with a throughbolted teak toerail. This is a strong type of joint, but there is some complaint of minor leaking along it in a few boats. The leaks are most likely one result of the relatively light construction of the hull skin, which has a tendency to “oilcan” in heavy weather, creating stresses at the joint.

The deck, also a solid fiberglass layup, has reinforcement designed into it during layup, so no interior metal backing plates are provided under winches, cleats, and other hardware. PS generally recommends backing plates behind high-stress hardware as a matter of course. We found little indication of trouble with leaking or working of most of the fittings, but one owner said that his lifeline stanchion bases had to be reinforced. This would be an area to inspect carefully.

Colors and non-skid surfaces are molded in, but due to the age of any Cal 40, the finish will look tired unless it has been renewed. A good Awlgrip job will do it wonders, and is probably warranted for this boat unless it is in general disrepair.

The deck and cockpit of the Cal 40 we inspected have numerous cracks in the gelcoat in corners and other stress areas. Check these areas closely—they are unsightly, but in most cases are not a structural concern.

Ballast is an internal lead casting dropped into the keel before the insides were assembled. If there is evidence that the boat has suffered a hard grounding, invesitgate the ballast cavity to see that it was properly repaired. It should not have a hollow sound when rapped, and there should be no cracks, weeping, or other evidence of moisture inside. Due to the construction sequence, major repairs could be awkward.

Wiring was also installed prior to the interior, which makes it quite inaccessible in some areas. What may be of more concern is that it is low enough in the boat to get wet if the last watch forgot to pump the bilges and the boat heels over to her work. That’s what happened to one owner, who lost all the electricity on the boat when approaching Nova Scotia’s Bras d’Or Lakes after an all night sail. Fortunately, dawn arrived in time to avert a navigation problem. They anchored in the harbor and found that the electrical system worked fine, once it got dry again. Before the next season rolled around, the boat’s entire electrical system had been replaced in elevated, accessible locations. The implication is that you should look carefully at the wiring in a Cal 40 before you make any decisions. If it has been replaced, try to learn who did the work and how well qualified he/she was for the job. If it has not, you may have to work the cost of rewiring into your acquisition expenses. We would suspect the worst until proven otherwise.

You might expect wheel steering on a boat this size, but the stock Cal 40 came with a big tiller. The boat is well enough balanced to be controlled with a tiller, and many helmsmen prefer it to a wheel, which masks feedback from the rudder and makes sensitive steering more difficult.

The cockpit is roomy, but properly designed for offshore work with relatively low volume, a bridgedeck and small companionway. The tiller sweeps the cockpit midsection, allowing the helmsman to sit fairly far forward, a help to visibility.

Winch islands are located aft of the helmsman, where there is room for the crew, but it also makes the sheets accessible to the helmsman for shorthanded sailing. The teak cockpit coaming has cutouts giving access to handy storage bins.

The aluminum mast is stepped through the deck to a fitting that meets it at the level of the cabin sole. The shroud chainplates are secured to a transverse bulkhead at the mast station, and then tied into an aluminum weldment in the bilges. This weldment also supports the mast step. While chainplates have been an area of concern in some designs, because they can work under the large loads they carry, our indications from Cal 40 owners are that the chainplate/shroud/mast step attachments have served well.

Sailing Performance

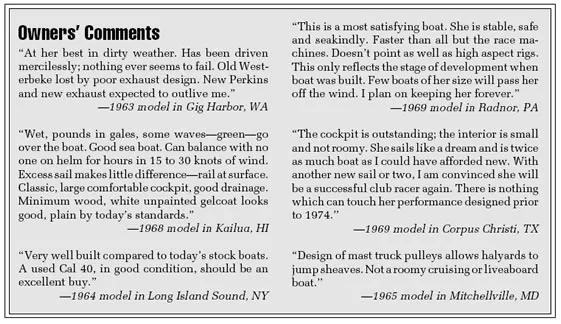

The Cal 40 is in her element in heavy air, especially off the wind. Her long waterline and flat bilges help her get up and go on reaches and runs, surfing in heavy air. On the wind, the flat hull forward pounds in waves and chop, which slows the boat somewhat and is irritating. Owners agree that she sails best with the rail in the water. She is not dry on the wind, so a dodger is a welcome feature.

The masthead sailplan allows relatively easy reduction of headsails to suit heavier conditions, and Cal 40 owners extol the survivability of their boats. “Simple rig, nothing breaks, strong, easy to use,” is a typical comment. Despite her stellar racing record, the Cal 40 is only ordinary in performance by today’s standards. She carries a PHRF rating between 108 and 120 seconds per mile, depending on the region. That’s about the same as a C&C 38 or an Ericson 36, both IOR designs of the late 70s. Compared to a mid-1970s design such as the Swan 38, the Cal 40 is a bit slower on the wind and in light air, a bit faster off the wind and in heavier going, about equal in speed overall. It’s not surprising that these boats perform alike if you look at the length of their waterlines and their displacements.

In comparing the Cal 40 to boats of her own vintage one sees what all the fuss was about. The Columbia 40, for example, is a 1965 Charles Morgan design, an “all-out racer” with a 27′ waterline, displacement of 20,200 pounds, and a PHRF rating of about 170. Or look at the Hinckley 41: 29′ on the water, 18,500 pounds, PHRF about 160.

The Cal 40’s waterline is almost 31′, but she displaces one or two tons less than the Columbia or the Hinckley, and rates nearly one minute per mile faster under PHRF. In that context, she is indeed a fast, light displacement boat with a long waterline. Just look at her “fin keel” and you can see the progression. Compared to a full keel with attached rudder, it is small. Compared to a modern fin keel, it hardly seems small enough to qualify for the name. If Cal 40s win races today, it’s because they are well sailed, not because the boat is the fast machine on the race course.

Interior

In the 60s, “accommodations” tended to imply the number of berths in a sailboat, and the more the better. It also included the notion of a basic galley with sink, stove, icebox, and a table of sorts, plus a head with toilet and sink. Space age electronics had not arrived in the galley or the nav station, nor had space arrived in the concept of the main saloon.

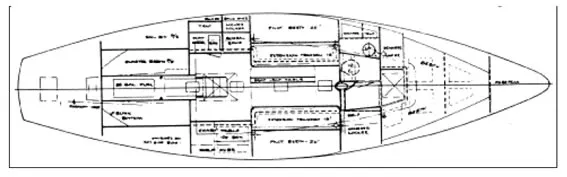

Inside, as elsewhere, the Cal 40 is well designed and functional, but she speaks of her own era. The layout is very traditional, with a V-berth forward, separated from the main cabin by a head and hanging locker. Pilot berths and extension settees port and starboard provide sleeping for four. The dropleaf table seats four, six if you squeeze. Next aft is the galley to port and a nav station to starboard, consisting of a chart table over the voluminous icebox. The galley has a usable sink next to the well for a gimbaled stove with oven.

Flanking the companionway steps are the entrances to the quarterberths, known affectionately as “torpedo tubes,” which gives you an impression of their dimensions. They extend from the main cabin through to the lazarette, which allows good circulation of air. In fact, on a return trip from Bermuda, one seasick sailor found great solace between tricks at the helm by climbing into one of the cocoon-like torpedo tubes, where he was washed with a fresh breeze from the dorade vent on the lazarette cover. The fact that the quarterberths flank the engine compartment doesn’t matter as long as you are under sail, but it’s a different story when under power.

So you have sleeping accommodations for eight, which is too many people on a 40-footer, except perhaps when racing. The extension transom berths, however, do not lend themselves to use under way. The interior, not spacious by modern standards, fills up fast with extra bodies aboard. Owners tend to convert some of the berths to storage space. The pilot berths are especially tempting for that use, but since they are also the most comfortable berths on the boat, the quarterberths are often sacrificed for storage.

One of the best features about the Cal 40’s interior is the dining table. Set slightly to port, it is supported by a sturdy sole-to-overhead stainless steel post at each end with a 4′ 4″ gimbaled mahogany tray between them above the table. The posts make excellent handholds, and the gimbaled tray can serve for everything from salt and pepper holder to bookshelf to diaper-changing table. The table has a drop leaf to port and to starboard, so it can be set up for use from the port settee without blocking fore-and-aft passage through the boat.

Engine

A variety of powerplants will be found in Cal 40s. Some early hulls were equipped with Atomic 4 gasoline engines. Later hulls got Graymarine 4-112 gasoline or Perkins 4-107 diesels. It’s likely that the original engine will need to be replaced if it has not already been done. Even the newest Cal 40s are rather old, and the early models have passed the quarter-century mark.

Boats in our files have Volvo MD2B, the Perkins, Pathfinder 50, Westerbeke 4-108, and Pisces 40 from Isuzu listed as replacements for the original engine.

The engine is located under the cockpit, between the torpedo tubes, which allow access to both sides, but are not especially convenient, particularly if the area has been turned into storage space. Better is the companionway ladder, which removes to expose the front of the engine. That can be an inconvenience, too, if the engine needs some attention while under way.

Used for the minimum requirements of a racing yacht, primarily getting in and out of port, you can probably make do with any of the engines. If the boat is to be used for cruising, with greater demands to be made on the engine, the Atomic 4 would likely be inadequate.

Generally the boat will do about six or seven knots under power, depending on the power plant and propeller. We suspect that many Cal 40s will have folding propellers, good for racing but not the best for powering, especially in reverse. The spade rudder set well aft confers good maneuverability under most conditons.

Conclusions

The Cal 40, a hot racing boat when new, carries that legacy with her into maturity. Generally, the boats have been raced hard, some cruised hard as well.Owners have tended to be the type to add gear and modifications to keep the boat comfortable and competitive. The boats are likely to have a large inventory of much-used sails.

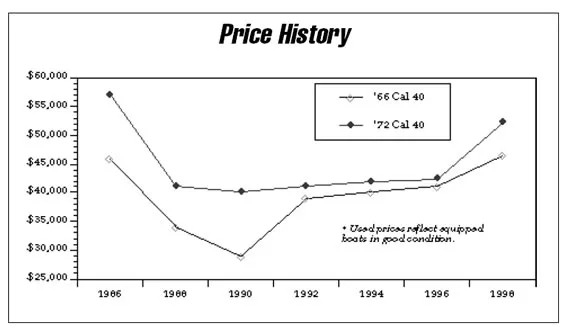

Because of her age and dated design, a Cal 40 may be available for much less money than a newer boat offering comparable quality and performance. Prices will vary according to the condition of the boat and gear, but will likely fall in the range of $40,000 to $50,000. If the boat has lots of add-ons in the galley and nav station, modern racing hardware, renewed standing rigging, new finish on the topsides, and the bottom is in good condition, it might fetch something higher. One performance extra to look for is a special (non-factory) fairing job on the keel and rudder that was available when the boats were young.

On the other hand, it should not be a surprise if there are areas that require attention, and you should calculate the cost of the work into the price you are willing to pay. Twenty or 25 years of hard sailing will take its toll. Significan’t expense could be incurred if the boat needs new wiring, an Awlgrip job on the topsides, extensive reinforcement of the interior furniture tabbing, a new engine, or new rigging. If racing is in your plans, new sails might be scheduled in as well.

This would be a good boat for a handy do-ityourselfer. Over the years, most of the boat’s problems have been solved more than once by other Cal 40 owners, many willing to share their wisdom. You would probably have a choice of solutions, and indications of which worked best.

Although there is not currently an active owners association, there persists a loose fellowship among present and former owners. If you buy a Cal 40, you will acquire a modest boat, with good pedigree and performance, and—should you desire them—a few new friends, as well.