So often, we come away depressed from what has become a rite of autumn-the boatshow. It’s the same old story-nothing new under the sun. Oh, the giants like Catalina and Hunter may have squeezed in a 36 between their 35- and 37-foot models, or Beneteau may have some bizarre portlight design that catches your eye. But, you know the refrain: The more things change, the more things stay the same.

There’s another reason why the anticipation with which we approach each new season soon falters: mediocre quality. As certainly as the leaves will fall, we will hear from friends and readers who after the show say they were appalled at some of the practices employed by boatbuilders: sloppy fiberglass and joinerwork, nonmarine grade parts, unsafe design elements and the like.

One might take this as a snipe at production methods, where cost cutting is the watchword, and that it is elitist to always demand better. We, like you, simply cannot afford top drawer. But still we like to look, and during the last year we’ve been aboard a handful of boats that just made us feel good to sit in the cockpit, a properly proportioned and contoured coaming supporting our aching back, running our finger over a tight mortise (no filler), and looking below to a cozy, well-appointed cabin, feeling drawn toward what designer Robert Perry calls the boy’s cabin-in-thewoods (which we understand as a sort of primal approach-avoidance behavior: seeking, and taking a mysterious delight in, a safe haven in the danger zone). Herewith are descriptions of three boats we’d be delighted to call our own, but due to financial constraints, probably never will.

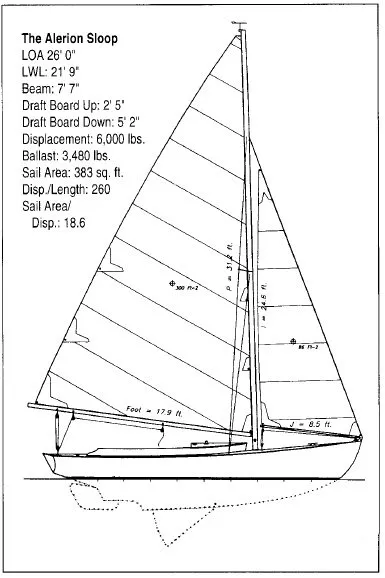

The Alerion

Nathaniel Herreshoff, the famed “Wizard of Bristol,” designed this 26-foot gentleman’s daysailer in 1912. We believe he built two himself, one ( which now resides at the Mystic Seaport Museum) that he sailed near his homes on Narragansett Bay and Ber-muda, and another, Sadie, that lives at the St. Michael’s Maritime Museum on Chesapeake Bay.

So the Alerion’s history is a long one: Nathaniel’s grandson Halsey designed a 25-foot fiberglass version for limited production, one of which was eventually bought by Alfred Sanford. In 1978 Sanford’s sons built a cold-molded wood version of the original Alerion on Nantucket (except that it was a half-foot beamier, toaccommodate a modest interior, slightly shorter on the waterline, and had a small cutaway in the aft section of the keel). They were beautifully made and the 20 sold are hard to come by on the used market. More recently, Carl Schumacher designed the 28- foot Alerion Express, which was first built by Holby Marine and now is built by TPI. The idea behind the Express was to combine the best elements of traditional looks with a modern “go fast” hull and appendages.

Which brings us to the latest incarnation of the Alerion, which is more or less faithful to Nathaniel Herreshoff s design (two differences: Capt. Nat’s hada gunter rig, and, unlike this adaptation, did not have a balanced rudder). It is built by Rumery’s Boatyard in Biddeford, Maine, and “represented” by Kingman Yacht Brokerage in Cataumet, Massachusetts. The hull is constructed of vinylester resin with a Divinicell foam core; the deck is cored with balsa. The house sides, coamings, toe rails, cockpit seats, cockpit and cabin soles, and louvered cabin doors are teak. The rudder post and hardware are bronze. The boat we saw had a Hall Spars aluminum mast (wood is optional) with Harken blocks, jiffy reefing, and a self-tending jib. Ballast is cast lead, internally positioned.

Rumery’s intends to build just five or six a year, so there is a good deal of latitude in fitting out. Hull #1 has overnight accommodations that include a V-berth, small galley, navigation surface and reading chair. One may choose a varnished oak or spruce ceiling. Optional is a Yanmar diesel (it seems almost sacrilegious to soil the bilge of this beauty with the oil that surely drips from an inboard).

We have two strong recollections of the Alerion. The first was in 1974, sailing Sadie on the Chesapeake Bay. The helm was effortless, and the hull seemed to move through the water with very little turbulence. She seemed not heavy, not light-just strong enough, and the proportions perfect. The second was perhaps 10 years later, on a rough day in Rhode Island Sound. We were hammering along in our Pearson Triton and came upon Ron Barr (who owns the Armchair Sailor bookstore in Newport) and a friend, seated low in the deep cockpit, their heads as well protected as could be expected in a boat with such a low coachroof. Indeed, one is nothing if not comfortable in the cockpit of an Alerion. Priced at $52,500 with sails, you’d expect as much.

Contact- Kingman Yacht Brokerage, 1 Shipyard Lane, Cataumet, MA 02534; 508/563-7136.

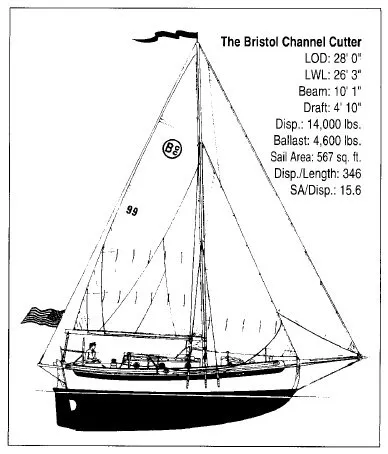

The Bristol Channel Cutter

Lyle Hess today is an old man, losing his vision, which must be especially tough for one who likes to designboats, spending hours at the drafting table. But what an eye he had! Probably best known as the man who designed Lin and Larry Pardey’s Seraffyn and Taleisin, Hess has also drawn several fiberglass production cruisers, including the 22-foot Falmouth Cutter and 28-foot Bristol Channel Cutter, or BCC for short.

The BCC, inspired by British work boats, is a heavy displacement cruising boat with a long waterline, short overhangs, full keel and big rudder. The cockpit, while small (it holds just 700 lbs. of water if filled) is quite comfortable, with generous backrests. The tiller does sweep much of its length, but is removable at anchor or when steered by a trim tab-type vane, as was fitted to Charles and Janet Smith’s boat when we went aboard in Newport Harbor this past summer. Theirs, called Freehand Steering, has a cloth vane attached to the backstay, which activates a trim tab hinged to the trailing edge of the rudder. This is a simple, very powerful type of mechanical self-steering.

Charles is 6′ 6″ tall. He told us he and his wife were looking for something larger than their Tanzer 22, a durable cruising boat in terms of both construction and aesthetic. They approached Roger Olson, one of the partners who bought the Sam L. Morse Co. in 1994. Roger had cruised a BCC for 13 years in the South Pacific and knows the boat intimately. (He tells a funny story about working in the voluminous lazarette one day with the cover propped open. The boat moved, the tiller swung over and knocked the cover down, the hasp locking at the same time. He pounded until his girlfriend returned from shore and rescued him from his embarrassing yet serious plight. The hasps on all BCCs are now installed upside down.) In production since 1980, the details are much refined.

Back to Charles and his height problem. Olson arranged (for three grand) to lower the sole 1″ and to cut off the coachroof of the cabin mold and raise the height 4″ so Charles didn’t have to wear a hard hat. They did an excellent job; it does not look at all ungainly.

The BCC is not a fast boat, but performs very well for what she is. If you read Ferenc Mate’s book, The World’s Best Sailboats, he will tell you about a BCC that made the 3, 150-mile passage from California to the Marquises in 22 days, averaging 5.8 knots, with a one-day run of 180 miles averaging 7-1/2 knots. That was Roger Olson, who, being a salesman now, will also advise you of these facts whether you’re interested or not. Certainly they are noteworthy.

The hull is solid fiberglass with 3/4″ bulkheads bonded on both sides to the hull; they even drill holes through the bulkhead so that the cured resin locks it in place.

Contributing to the appeal of the BCC is the scuttle hatch forward. This not only looks salty, but provides a secure deck area just abaft to work the mast. The drawback is the need to stoop when going forward from the saloon to the head, which is located under the hatch. The 8″ bulwarks, bowsprit and bronze portlights continue the theme.

This is a go-anywhere boat, which, like the Alerion, is a piece of furniture (we’d varnish the raw interior teak pretty damn quick) that you hope your children will cherish when you pass on. The Smiths paid about $140,000 when all was said and done (radar, steering vane, sails, etc.). Base price is $122,500. The smaller Falmouth Cutter sells for $74,900.

Contact- Sam L. Morse Co., 1626 Placentia Ave., Costa Mesa, CA 92627; 714/645-1843.

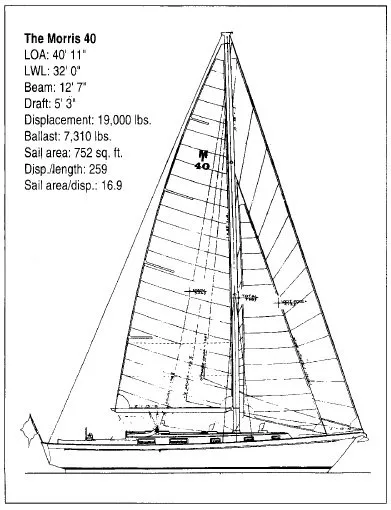

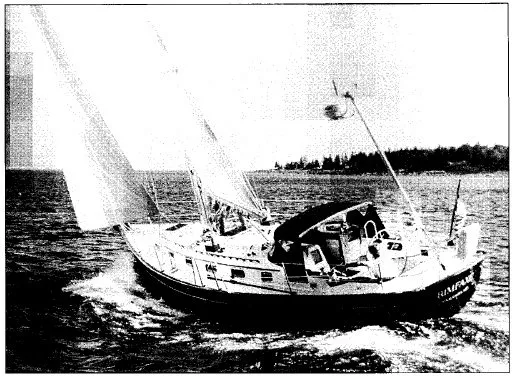

The Morris 40

Tom Morris has been working the European market for some years now, principally Great Britain. In 1980, he licensed Victoria Marine to build his Frances 26 and Leigh 30 as the Victoria 26 and 30. Now he is licensed to build the Bowman 40 as the Morris 40. All are designed by Chuck Paine, a union too successful to mess with.

Paine says that he and Morris “Americanized” the Bowman for the U.S. market. This involved adding 11″ to overall length, a bulb keel, taller rig and reduced weight. He calls the Morris 40 the “ultimate short-handed offshore yacht with sufficient speed for racing potential.”

Morris eschews cored hull construction, but over time has felt the need to reduce the weight of a solid fiberglass hull. He now uses what he calls Rib-Core construction, which he says, “is engineered using longitudinal and transverse stiffeners encapsulated in the final inside laminate supported by the interior monocoque structure bonded to the hull and deck.” This makes for a stiffer hull and a weight savings of 25% . A cored hull, he estimates, would save an additional .9 lbs. per square foot of hull laminate. He makes up some of the difference with a few tricks such as using cored bulkheads. We think it’s a very sound approach. We also like the fact that he uses all vinylester resin in the lay-up-more expensive, but with superior bonding and blister resistance properties. If you want to know more, read our review of the similarly constructed Morris 44 in the March 15, 1994 issue.

The low-profile coachroof provides excellent visibility for the helmsman, even without a humped seat. The side decks are wide and the foredeck easily worked. A custom weldment carries two anchors ( we always anchor with two-a lightweight and a plow-a practice encouraged if they don’t have to be untied or lifted out of a locker).

The engine is located under part of the galley, close to midships. Paine says this “further improves windward ability by reducing the mass moment of inertia of the yacht in pitching mode.” (Chuck, where were you when we were attacked by readers for saying that keeping the ends light minimizes hobby horsing?).

The interior, of course, is exquisite, with much allowance for customization. It is essentially laid out for two couples (two double berths, two heads), though families could opt for single berths to separate the children. The joinerwork is as good as any we’ve seen, here or abroad. Varnishing it will cost about $17,000, but having varnished the interiors of several boats ourselves, we are beginning to understand why it costs so much.

The Morris boats are, to our minds, a very successful combination of Paine’s enduring style and Morris’ quality construction; add the maximized performance obtained from the pared-away underbody and intelligent weight reductions and you get a boat that sails much quicker than it looks. The price sheet starts at $345,000, and the next slot in the production schedule is March 1996.

Contact-Morris Yachts, Clark Point Rd., Southwest Harbor, ME 04679; 207 /244-5509.