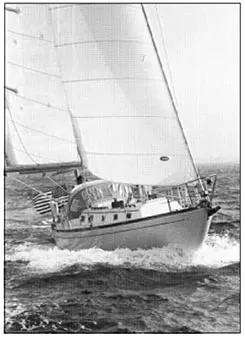

Eric Woods, wearing shorts and sneakers, and a baseball cap with the bill backwards, looks a lot like Johnny Carson as he finishes setting the mizzen staysail and jumps back to the cockpit. He has the same impish grin, the sort of grin a 10- year-old boy has after dropping a frog down a girl’s dress.

It’s no accident. He’s just launched hull #10 of Migrator Yachts’ version of the Block Island 40 yawl, we’re steaming along at better than seven knots, and he’s happy. Really happy! And why not? After a lifetime in the boatbuilding business, and a longtime love affair with the BI 40, he’s finally his own boss; his two sons Rob and Eric, who work with him, are sailing a sistership abeam of us; sales are picking up; and, hey, this is a perfect day!

History

Richard Henderson, in his book Choice Yacht Designs, credits the inspiration of the Block Island 40 to the Sparkman & Stephens-designed , a centerboard yawl that won the Bermuda Race three consecutive times. That boat led to the production model Nevins 40, and later to several similar boats by other designers. The Block Island 40 and Hinckley Bermuda 40, both drawn by William H. Tripp, Jr., are the best known.

Tripp’s first effort along these lines was the Vitesse class, which he designed in 1957. It was constructed in the Netherlands, and imported to the U.S. for Van Breems International. Not long after that the American Boat Building Corporation of Warwick, Rhode Island, purchased the molds, changed the name, and built 22 boats before in turn selling the molds to Metalmast Marine, Inc. of Putnam, Connecticut. Metalmast, which built 14 of them, at one point commissioned Tripp to modify the underbody by separating the keel and rudder. They also gave the rig a higher-aspect ratio mainsail.

Numerous accomplished yachtsmen have owned or do own Block Island 40s, among them John Nicholas Brown and Volta, Niebold Smith and , Benjamin DuPont and Rhubarb, Van Allen Clark and Swamp Yankee. The BI 40 dates to a time when you could own a true dual-purpose boat, equally adept at racing and cruising. Today, unfortunately, it’s a rare boat that so qualifies.

In time the molds grew weary and were retired. Until that is, Eric Woods decided to leave his job at C.E. Ryder Corp. (builder of Sea Sprites and Southern Crosses). He and his wife Joan had been interested in having a BI 40 built for their own cruising pleasure. Metalmast declined to build the boat, but said they’d sell him the molds so he could do it himself. Accidentally and providentially, Woods found himself in 1985 completely retooling the molds and forming his own company for the dubious purpose of building a 1957-vintage yawl. “The more I sail this boat,” he told us, “the more I’m convinced this a better boat for cruising than most of the newer models on the market.”

Woods’ Migrator Yachts hasn’t exactly taken the world by storm, but he’s survived some of the toughest years in the sailing industry.

The Design

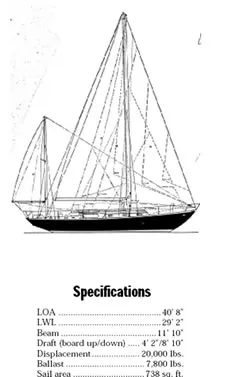

The BI 40 enjoyed a successful racing career (largely under the CCA rule), which may surprise younger readers whose experience begins with the IOR, IMS or PHRF. The long overhangs quickly immerse when heeled, adding to sailing length, which, of course, relates directly to speed. Freeboard is relatively low, and the keel is long, with a nice flat run. The rudder is attached and the propeller is located in an aperture.

The standard rig is a yawl, though a sloop is possible. Woods, however, says he’s delivered only yawls, and isn’t sure he’d want to build a sloop, believing as he does in the advantages of a two stick rig. Because centerboard boats tend to have someinitial tenderness in moderate to higher wind velocities, the ability to drop the mainsail and jog along nicely under jib and mizzen is very attractive. This option keeps the center of effort low.

At 11′ 10″, the BI 40 was quite beamy by 1950 standards, and still provides a nice wide platform by today’s standards. A trademark of both the BI 40 and Hinckley B40 are the wide side decks, which enable one to walk forward without ducking or sidestepping the shrouds. This also moves the settees inboard, providing generous stowage outboard as well as minimizing distances between handholds-important features for cruising and rough weather safety.

Woods has made several changes, which aren’t immediately obvious, but nevertheless important.

He gave his version a more hydrodynamic centerboard (solid fiberglass weighted with lead) for improved windward performance (Woods likes to adjust it to about a 45-degree angle). Off the wind, the board is completely retracted.

Aware that interior volume of the original design was limited, and that so many boats are purchased based on livability, he also lengthened the cabin trunk fore and aft. This has allowed him to install a true U-shaped galley and sit-down chart table, features not found on earlier BI 40s or B40s.

A minor improvement was cleaning up the aperture for a smoother flow of water over the propeller. Ever mindful of performance, Woods is a strong advocate of a three-bladed feathering Max Prop for less drag and better performance backing down.

By nearly any standard, this is a handsome yacht, indeed, what many folks would call a “proper yacht.” It’s sure to draw praise in any harbor.

Construction

Woods has assiduously followed developments in fiberglass boatbuilding technology. While there is nothing particularly high-tech about the layup, he’s doing what he’s supposed to for this sort of boat: combination 1-1/2-ounce mat, 18-ounce biaxial, and 24-ounce directional fiberglass set in polyester resin with an isopththalic gelcoat. The first two laminations are vinylester, which as we have reported has proven superior in preventing blistering. Airex core, 5/8-inch thick, is standard. The deck is balsa-cored.

Hull #10 was given a Ferro Copper Clad treatment on the bottom. It’s 14 mils thick, adds 126 pounds to the hull, and costs $3,500. Woods, as well as some other builders such as Tom Morris, believe that Copper Clad is very cost effective, even if it doesn’t last as many years as the Ferro Corp. claims (15 years- plus). It also looks great.

The interior is all-wood and though perhaps not finished to the same degree of perfection as a Hinckley, it is very nicely done. Bulkheads are tabbed to the hull. Ceilings are ash. Joinery is teak-faced plywood or solid teak. Mahogany is used where concealed. Locker doors are louvered. The headliner is foambacked vinyl, and is removable. Eleven opening portlights, two hatches and two Dorades provide excellent ventilation. The only fiberglass pan is in the head, where moisture and shower water make this the correct choice.

The hull/deck joint is bonded with 3M 5200 and through-bolted every six inches.

The standard auxiliary is the Yanmar 4JHE 44-hp. diesel with 2.17:1 reduction gear.

Performance

In its heyday, the BI 40 had a good racing record. In the 1960 Bermuda Race six of the first 11 places were won by BI 40s, and in 1978, the BI 40 Alaris won her class. Its PHRF rating varies between rig (sloop or yawl) and fleet from a low of 156 to a high of 186. The average seems to be 165. It’s difficult to make comparisons, but more contemporary boats with similar ratings include the Hunter 33, Irwin 34 Citation and Island Packet 38. But what’s the point? The BI 40 is not a round-the-buoys racer. She’s a cruising boat displacing 20,000 pounds.

Upwind is never the forte of a centerboard design, though the BI 40 delivers decently. In 20- to 25-knot winds with just jib and mizzen, we were able to make good speed with the apparent wind at 30 degrees. The ability to proceed safely and comfortably without the mainsail is an advantage that must be experienced to be appreciated-no excessive heel, no sudden heeling in gusts, no mainsail noise.

On our return to Marion, Massachusetts, with the wind just aft of the beam and the Buzzards Bay chop pushing us, we set the mainsail and mizzen staysail. It was a delightful romp, with speeds of eight knots. The helm was nicely balanced. It was, as the saying goes, one of those days that God will not subtract from our allotted time.

Interior

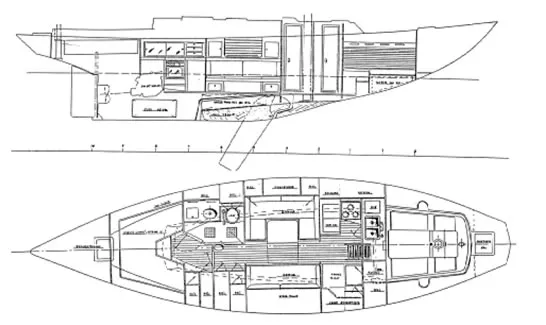

The drawing shows the essentials of the BI 40 interior. Not so obvious is the large forepeak, separated from the forward cabin by a watertight bulkhead. Access is by means of a hatch in the foredeck. Inside is plenty of room for sails and ground tackle. Some customization is possible. For example, Woods has built boats with nav stations oriented either fore and aft or athwartship. Note also the generous number of stowage areas, including the four hanging lockers opposite the head, bins behind the port-side settee, and the wet locker right where it should be-next to the companion way. One owner opted for a quarter berth aft of the nav station, but Woods warns about the amount of stowage space lost. Headroom is 6′ 1-1/2″ in the main cabin, slightly less forward. Berth lengths range from 6′ 4-1/2″ to 6′ 7″. Foam cushions are 6 inches thick.

It is no secret that many boats are purchased on the basis of the interior. Without being chauvinistic, it is often the wife, nearly oblivious to the deck and rig, who either blesses or condemns her husband’s choice based on her impression of the interior. This may mean many things, such as overall spaciousness, large galley, adequate stowage. The BI 40 shows well on all counts, though not by some contemporary standards, where the settees are moved outboard to the hull, freeboard is raised as high as possible (often necessitated by bolt-on keels and shallow bilges), and extra berths are shoved in where possible, sometimes even under the cockpit. After viewing, say, a Hunter 40, in which the accommodations have been pushed into the extreme ends of the hull, the BI 40 interior may appear cramped. Such comparisons infuriate Woods, and rightly so. The BI 40 is an honest cruising boat for a couple or small family. Its long overhangs are very traditional. It has adequate tankage (120 gallons water, 45 gallons diesel) and stowage to really go somewhere, a fact that cannot be appreciated until you’ve gone. The low freeboard helps performance. The wide sidedecks promote safety. All of the berths in the main cabin make comfortable sea berths (you can’t sleep in chairs, fashionable in some modern boats). In short, this is an excellent interior arrangement for real cruising.

Conclusion

Over the eight years that Woods has been building BI 40s, he’s made numerous small refinements, such as adding a ball-bearing Lewmar traveler to the stern pulpit for trimming the mizzen more efficiently. Breast cleats amidship. A new outhaul and reefing arrangement. Gradually increasing the height of the toerail as it approaches the bow. And he’ll work with customers to incorporate their ideas insofar as the basic structure and concept allows.

We can find little to fault in Woods’ version of the BI 40. It won’t be the right boat for everybody-none is. If you’re planning on living aboard at a dock, you can get more space for your buck. If you must have 8- inch teak bulwarks, look at the Lord Nelson or Hans Christian. If you must have more speed, especially upwind, look for a divided underbody.

If it isn’t apparent already, we’ll admit it here: This is our kind of boat. Moderate displacement. Long keel and attached rudder. Prop in an aperture. Low freeboard. Clean decks. Easy to handle. Strong construction. Good looks. Altogether, a wholesome thoroughbred. But then, ours is a cruising mentality.

The 1992 price was $198,000, fully commissioned including sails. The BUC Research Used Boat Price Guide lists those BI 40s built by American Boatbuilding as selling between $31,500 and $48,500. A 1976 or 1977 Metalmast BI 40, the last years that company built the boat, sells between $63,000 and $72,000. Because not that many were built, and because most owners seem to hang onto their BI 40s until death do them part, they are seldom seen on the used market. If you really want one, you’ll probably have to have Migrator Yachts build one for you. We should all be so lucky.

I used to sail on a BI40 that initially plied the waters of Lake Michigan, I believe it was called Bantou (sp?) and Fury prior to being purchased and sailed on on a large inland lake in Wisconsin, Winnebago. It had been reconfigured as a sloop. It had all of the wonderful sailing qualities mentioned above, even with an ancient rig. It was gorgeous. Beam reaching in a blow was heavenly. This my first Practical Sailor article. Mr. Nicholson’s article is perfectly written and informative. Nice work.