Beneteau is the largest builder of sailboats in the world. The French company has made its mark not only in Europe, but in the U.S. as well, opening some years ago a plant in Marion, South Carolina, with headquarters in Charlotte, North Carolina. Probably more than any other company, Beneteau also has influenced sailboat styling—the so-called Euro-style, typified by smoked wrap-around windows, scoop transoms with molded-in steps, and lots of curvy interior shapes. The Oceanis 350, built between 1986 and 1993, is a reasonable example of Beneteau’s impact on the sailboat market. About 144 were built in the US, more in Europe.

The Design

Philippe Briand, a prominent naval architect in France with experience in the America’s Cup arena, was commissioned to design the Oceanis 350. Performance is important to Beneteau; indeed, many of their boats are successfully raced, though most of those belong to the First line. The Oceanis line, which over the intervening years has or does include the 281, 321, 351, 370, 390, 430, 440, 44cc, 500, and 510, are marketed more as sexy, performance cruisers. Indeed, the Oceanis 350 is a striking design with its low-profile coachroof, smoked “skylights,” and wide, scooped transom.

The hull is of fairly light displacement; the displacement/ length ratio is 178, meaning there is not a lot below the waterline, including bilge. The keel is essentially a cruising fin, with a raked leading edge and a flat run on the bottom. A 4′ 2″ shoal draft wing keel was standard; optional was the 5′ 2″ fin without wings. The rudder, which one owner said was heavily built, is a balanced spade behind what designer Bob Perry calls a “skeglet.” The prop shaft exits through a short supporting skeg. With a sail area/displacement ratio of 16.2 (generous, but not excessive by any means), she sails quickly in all but light air conditions.

Though the name 350 implies 35′, LOA actually is 33′ 10″ with a long 29′ 10″ waterline. The beam of 11′ 3″ is considerable for a boat of this length, but that is the trend today because it increases interior volume and contributes to stability. Unfortunately, wide beam also can make a boat squirrelly to handle in certain conditions.

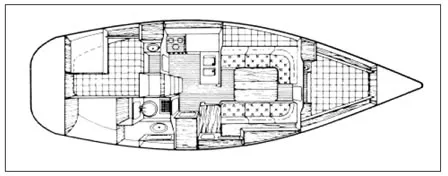

Because of the aft cabin (an appealing feature to most owners), the cockpit is slightly elevated, and one owner said the backrests, while comfortably angled, were a bit short. The same owner praised the scupper system (“The best cockpit drain well I’ve seen”) and propane tank storage compartment, with room for jugs of gasoline for the dinghy outboard and reserve diesel fuel. The bridgedeck is at the same height as the cockpit seats, and is a good safety feature, though the ladder, by necessity, is a bit steep. We’d rather have the bridgedeck than a low companionway with fewer steps.

A charter version of the Oceanis 350 was offered with double aft cabins (built only in France), which appear to reduce the size of the starboard cockpit locker and the head.

The rig is a masthead sloop with double spreaders slightly swept back to eliminate fore and aft lower shrouds. A baby stay helps keep the mast in column and from pumping.

Construction

The boat is built of solid fiberglass, deriving much of its structural integrity from a complex liner with molded floor frames for rigidity. The liner is bonded to the hull, but as we have said many times, it is difficult if not impossible to determine how well this has been done as access through the liner is often limited. And we could repeat that liners offer less thermal and acoustic insulation than wood, and so tend to make for noisier interiors that also condense moisture more easily, but the man-hours required to construct an all-wood interior are prohibitively expensive on most production boats.

Bulkheads, instead of being glassed to the hull, fit in channels in the hull and cabin liners and are then epoxied. Again, this is perfectly adequate for most kinds of sailing, but they can begin to work (move slightly), and if you want a boat to take on long offshore passages, it’s better to have the bulkheads directly bonded to both the deck and hull.

The deck is cored with end-grain balsa, as is almost standard practice these days, and is joined to the hull with a shoebox flange that is, according to an owner, riveted on 6″ centers and only through-bolted at the stanchion bases. He felt that the bases were not sufficiently large and, ironically, the only leaks he’d experienced were at these bolt holes. The toerail hides the hull/deck joint.

Iron ballast is external, with keel bolts screwed into steel inserts or plugs cast into the keel. Lead would be preferable from the standpoint of higher density and lower maintenance. Winglets on the shoal keel model were bolted on.

One owner said the anchor locker cover is “flimsy and has a large hole in it.” It is possible to install a windlass inside the anchor compartment, which keeps it out of the way and protected from the weather.

Another owner said the aluminum deck castings— including the stern anchor roller, fairleads, cleats and bow roller—”are excellent and heavy duty. The bow roller, however, is too short to handle an articulated plow. Unless tied at an angle, the plow will hit the bow in a seaway.”

Most of the hardware, naturally, is made in France, and while generally of above average quality, replacement parts can be hard to come by. The owner of a 1988 model said his Goiot roller furler developed excessive friction and that he had difficulty getting parts for it as well as the Optimus stove and Plastimo bilge pump.

A number of owners complained about the electrical system. “The panel used electronic circuit breakers mounted on a printed circuit board,” wrote an owner. “The heavy electrical wires were directly attached to the circuit board through a soldered terminal strip. The movement of the wires gradually fractured the small leads between the terminal strip and the PC board. I eventually rebuilt the PC board.”

Another owner, who also said he had problems with the electronic touch-button breakers, added that wire diameters were too small, not tinned, and that voltage drops were excessive. “Even now,” he wrote, “cycling of the freshwater pump turns the stereo off or on—Handel’s Water Music maybe?”

There were some comments about the wraparound skylight leaking and outgassing of the adhesive, but owners commend Beneteau’s after sales support in dealing with the problems.

Interior

The light ash veneers used below give the cabins an airy feel that is seldom possible with teak. However, one owner said the veneer easily dents and gouges, sometimes turning dark with moisture.

The three-cabin layout on most 350s offers private accommodations to at least two couples, though one owner noted that because of “trying to cram three cabins in it, this boat is for small people.”

The head is located in the aft starboard quarter area and came standard with a toilet, pressure hot and old water, an opening portlight, mushroom vent and locker space.

The galley opposite has a 2-burner stove with oven, double sink, Frigiboat 12-volt refrigeration, icebox, dustbin, opening portlight and adequate stowage, though one owner noted that pots and pans have to be kept in the wet locker.

Another owner said that “The galley has a very nice slide-out, multi-level storage area under one sink. The other under sink [area] is a nightmare of exposed through-hulls, pumps and hosing—a very poor design. The smallish, deep round sinks are very with water, don’t slop, hold wine bottles and coffee urns securely in a seaway and, most importantly, avoid the appearance of tract house double sinks surrounded with faux marble Corian and overhanging wine glass racks.

The icebox is well insulated, holding ice for four days in tropical climates. Freshwater tank capacity is 82 gallons.

The dedicated nav seat intelligently faces aft, which facilitates communication with the helm.

Except for the head, owners were nearly unanimous in declaring that ventilation below is inadequate, with just one on-deck vent in the head, and a forward hatch that is too small to pass sail bags through.

Performance

Most owners agree that the Oceanis 350 balances well and is reasonably seakindly, though one owner said, “The bow will pound if it hits high waves dead on,” while another said, “This boat really never pounds.”

The boat’s light air performance also is a bit less than some would like: One owner said, “My main complaints are not enough sail for winds under 6 knots; in winds over 20 knots or on a beam reach, I have to reef the main to keep the boat balanced.”

“The boat does not carry much sail, and consequently does not perform well in light winds,” confirmed another. “However, when the wind gets above 13 knots the boat becomes quite quick. The boat will easily sail 8 to 9 knots when the wind is in the 20 to 25-knot range.

The wide stern of the Oceanis 350 “tends to wander a bit in a large following sea,” according to an owner. This is to be expected, a the trade-off between generous cockpit volume and handling.

The boat points reasonably well, better with the deep fin than the shoal draft wing keel.

An interesting comment we have not heard before came from an owner who said that the wings sometimes foul a second anchor rode, necessitating chain or catenary weights. Narrow sheeting angles aid windward performance.

The Oceanis 350 is powered by a 28-hp. Volvo 2003 diesel that is easily serviced and will cruise at 7 knots with 2,000-2,200 rpm. Fuel capacity is 21 gallons. While the Volvo is a pretty good engine, replacement parts tend to be expensive.

With its high freeboard, handling dockside maneuvers in a cross wind can get tricky.

Conclusion

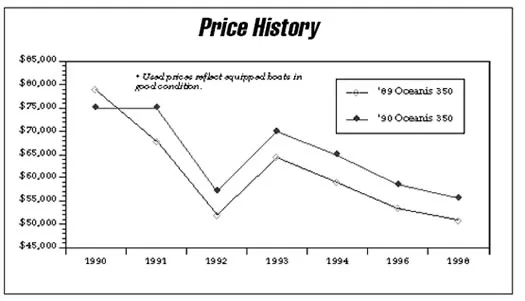

Construction of the Beneteau is average to above average for such a production boat. Good looks and a versatile interior seem to be its main selling points.

Criticisms focus on the electrical system, parts availability, and light air performance. Beyond that, the owners who responded indicate that, all things considered, the Oceanis 350 offers modern styling, good handling and decent speeds in a reasonably priced package.