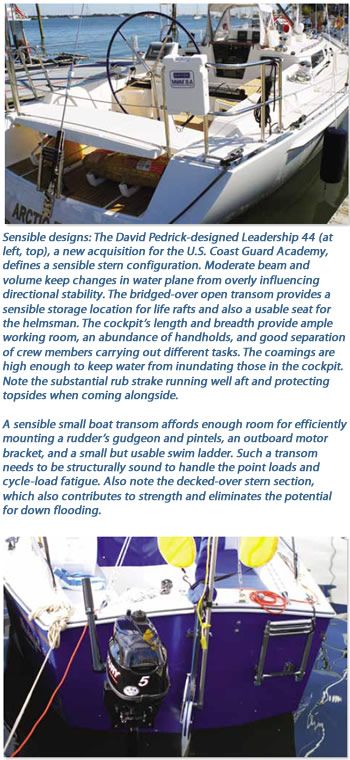

Photos by Ralph Naranjo

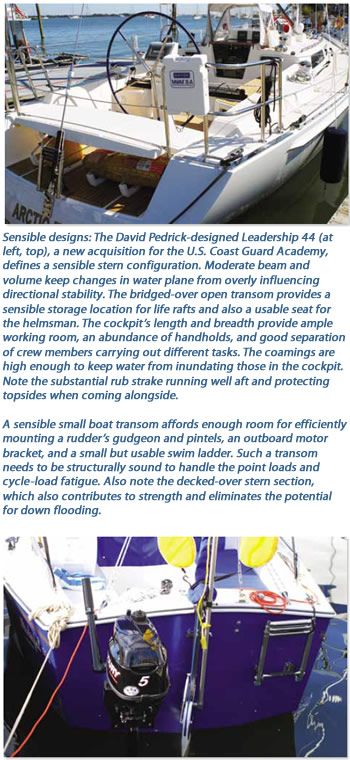

Nothing stereotypes a cruising sailboat more than whats going on at the bow and stern. Both ends of the boat tell a lot about cruising preferences and what assets and obstacles will arise in a seaway.

In the January 2013 issue of Practical Sailor, we took a close look at the bow and noted the trend toward plumb stems, multiple furlers, and a longer resting waterline. We also recognized the tradeoffs involved, such as the need to perch the anchor further forward on a mini sprit or small strut in order to keep the flukes from chewing away at the topsides. When it comes to ground-tackle handling, its clear that for decades, cruisers have understood and retained a commitment to anchor deployment and retrieval-and designers and builders have responded appropriately. However, an even bigger shift in yacht design has overtaken the aft end of the modern production sailboat-and the implications are hard to miss.

During our dock walks at this past years boat shows, PS editors focused on the back of the boats, and here we delve into the implications and look of modern stern design and what this means for those underway and those enjoying a remote anchorage.

More Beam Aft

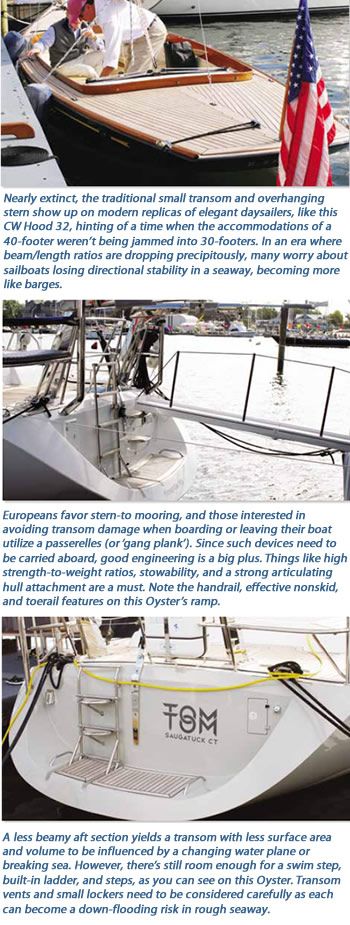

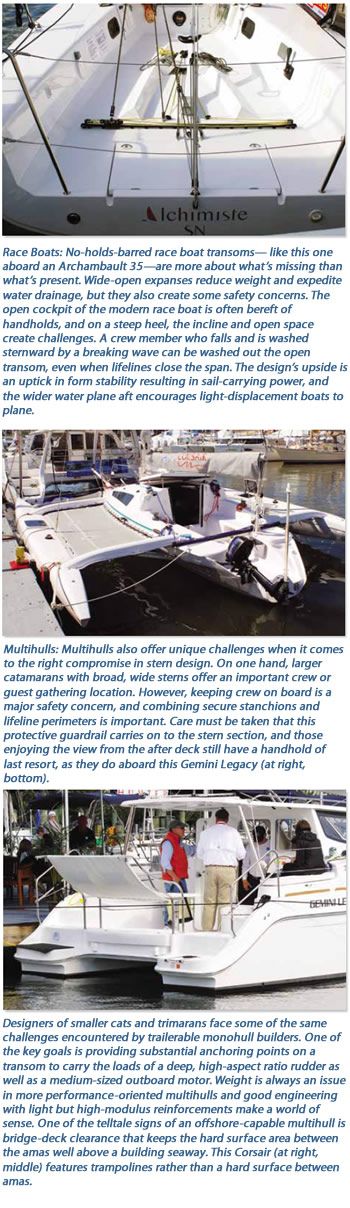

The first of these is the trend toward more beam aft and its growing acceptance among racing and cruising sailors. Performance sailors see that the uptick in form stability equates to extra sail-carrying capacity and a hulls willingness to climb onto a plane during power reaches. Designers realized that placing a hydro-dynamically shaped bulb at the bottom of a very deep fin keel attached to a wide canoe-shaped hull can deliver enough secondary righting moment to make the pizza slice-shaped resting waterline adequate for offshore sailing. However, when such water-plane footprints show up in the cruising fleet, they often arrive sans deep keel and with lower ballast ratios, considerably less draft, and a shortfall in secondary righting moment.

Many naval architects see the plethora of wide, shoal-draft, sub 30-percent ballast ratio cruisers as perfectly viable inshore/coastal cruisers, but they balk when it comes to the boats appropriateness for offshore use. We agree, and in an upcoming issue, we will address making sense of stability indicators, the ISO STIX formula, and whats involved in staying right side up.

The glass half-empty squadron likes to sneer that the new ultra-wide sterns are there to expedite boarding at boat shows. But summertime, warm-weather coastal cruisers seem to like the supersized sundecks and the beckoning easy access to the water. Fewer and fewer boats provide the traditional deep well, small cockpit feel that offered kind motion and good protection from spray and breaking waves. Todays cockpits have more of a wide-open feel, and the offshore passagemaking symbol of a lean double-ender with a self-steering vane securely bolted to the trailing edge has become pass-at least, thats the case among the fleet at boat shows.

We see some significant up sides to the new trend toward connectivity to the sea and attributes like a cockpit with a picnic table. But not all of these features favor offshore passagemaking.

Wide-open Cockpits

One issue that rose above the rest is that an ideal stern section and cockpit layout for the racer is anything but the right solution for the cruiser. Crews differ in size, rail meat is an alien concept to most cruisers, and obsession over mark roundings and the speed of a sail change diminish. In some ways, its like defining the right car design for a Baja 500 and a soccer mom. Add to this the inshore and offshore renditions of cruising, and its a bit of a surprise that all user groups are being led to boats with big broad transoms and maximum beam moved further aft.

The room-to-roam feeling of open space and increased deck area does afford a big-boat feel and may be a welcome attribute at anchor. But as one crusty naval architect I know put it, fiberglass is cheap, and space is free. The real question is whether the added area is an all-around asset. A closer look shows that along with bringing the beam aft, builders have added twin wheels at opposing stern quarters, and on many boats, one can use the pushpit as a backrest and steer with an unencumbered view of what lies ahead. However, the very same trajectory in open-ocean sailing is the antithesis of deep-well cockpit protection. The bimini does nothing to halt sea spray or deflect a dollop of green water. Many wide cockpit designs lack adequate handholds, which can be problematic in a developing seaway. The closer we looked, the more we felt that these room-to-roam stern sections were at their best sailing flat, but when significantly heeled in a pitching seaway, the big advantage of a wide stern, with a helm at each quarter, came into question.

During our boat-show tour, as we stepped aboard each boat, we mentally turned the tranquility of a boat-show slip into varying angles of heel and different degrees of sea state-induced boat motion. Mimicking the way a designer heels a hull using a Rhino CAD program, we imagined a 15-degree heel, increased it to a caught over canvassed 30-degree heel, and punctuated the steep angle with some three-dimensional pitch, roll, and yaw gyrations. We focused on what would be going on at the helm(s) and how getting from here-to-there across a spacious, but inclined cockpit would up the chances for an undesirable slip or fall.

In millpond conditions, the distance you are from the vessels centerline and center of buoyancy goes unnoticed. But add some imaginary pitching, sporadic wind gusts, and wave impacts to your mind-modeling, and picture what an imaginary helmsperson perched at the windward helm of a wide transom sloop would be encountering. The person at the helm would indeed be in full contact with the elements. They could move to the leeward helm, and the extreme beam carried aft would block some of the wind and spray, along with visibility of whats going on the windward side of the boat. Many salesmen tout the clear open pathway down the centerline of the cockpit and how the wheels perched toward the rail are well out of the way. In short, many of the big fair-weather advantages of the wide-open cockpits go away when conditions deteriorate.

Davits on a Wide Stern

A wide, full stern affords a lot of buoyancy along with a span thats wide enough to accommodate davits for hoisting a dinghy while making a near-shore or coastal run. However, there are important design criteria to consider before deciding to carry a good-sized RIB on davits. The first thing to recognize is that any extra weight added above the center of gravity (CG) decreases a sailboats angle of vanishing stability (AVS), and many wide, shoal-draft, low-ballast-ratio boats have very little to spare. We are starting to see an increase in sailboats with low AVS ratings (110 or less).

Not only is a low AVS undesirable for offshore cruisers, but it means that any extra weight and windage added above the CG can increase the risk of capsize and interfere with swift recovery. In addition, when heeled precipitously, a RIB in davits is very vulnerable to breaking seas, and no davit structure is engineered to withstand the impact of thousands of pounds of green water. Those running the Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) or coastal cruising and watching the weather forecasts have better odds when hauling a dinghy in the davits. Those on lengthy ocean passages are upping the ante.

Dual Helms

With dual helm stations comes a dual-flywheel effect that impacts the efficiency of a boats autopilot. Add to this the extra cables or drag links associated with connecting both wheels to the steering quadrant on the rudder stock, and its obvious that there will be more friction in the system and more components that can fail. Those making long passages shorthanded and relying on an autopilot need to consider such factors.

Hardware

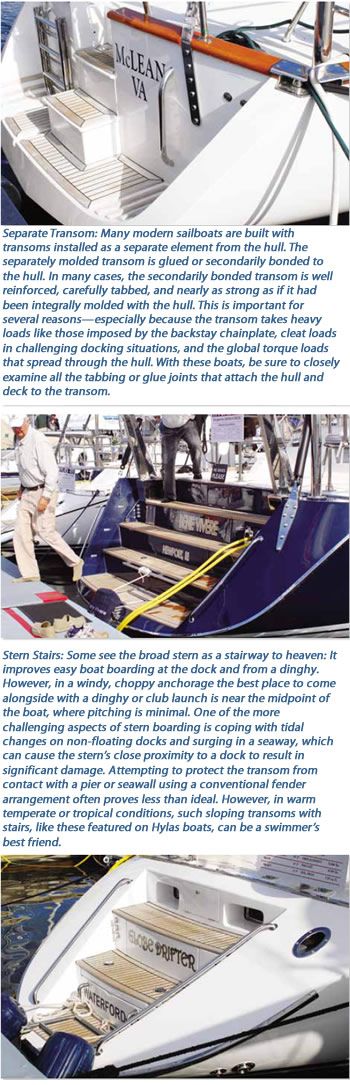

Cleats and chocks are another key feature of every cruising boats stern quarter. Not only do they need to be securely anchored and backed, but they must be easy to work. They may be used for mooring, attaching dock lines, or affixing a drogue bridle, and the loads imposed can be substantial.

By crawling into an aft locker with a flashlight, you can usually see how the hardware has been attached to the deck. Look for backing plates, large shoulder washers, and fasteners penetrating the hull-to-deck joint (with inward-turning flange joints), because this is where solid fiberglass replaces core material. Large cleats and chocks are an asset as long as they have been well attached to the deck.

Conclusion

The take-home point is that before deciding whether a boat is right for you, you first must know how your boat will be used; then determine whether or not the design attributes of the stern and cockpit layout make sense.