We often think of safety on deck in terms of PFDs, lifelines and jacklines, but the falls they protect against only happen after something else has gone wrong. Some of the most serious injuries and even fatalities happen without ever leaving the deck.

We’re here to help prevent that. Some of our suggestions may be aesthetically pleasing, while others sacrifice beauty for safety. Function comes first. For most of these observations, we’ve drawn from both experience and ISO 15085:2003 “Small craft — Man-overboard prevention and recovery,” the international standard that yacht builders follow to ensure onboard safety.

Before we launch into our list, we should mention a few relevant reports.

• “Raising the Bar on Lifelines”

• “Refinishing Your Boat’s Non-Skid”

• “Jackline Materials Evaluation”

SCOOT, CRAWL, CROUCH, OR WALK

How to move should be at the top of your decision tree when the weather get’s wild. I often hear “lifelines are too low to do anything but trip me,” but that’s only true if you are walking when you should be scooting. Many times I’ve worked at the bow with the boat playing submarine with the square-faced head sea.

On these occasions, I keep one tether on the jackline, clip another to the pulpit, and sit down. With the pulpit armpit high, I am very safe. I’ve been walking on wild decks for decades and actually enjoy it, but I also know when it’s time to sit down or scoot.

AVOID THE BOOM

Lack of awareness of the boom is responsible for many serious accidents and a number of fatalities. If it’s low, you stoop and inform your guests to do the same. Oddly, people tend to be less aware of the danger of an accidental jibe when they step out of the cockpit and onto the cabin roof, or side deck, where the boom may be impossible to duck. But there are options. A boom brake can slow the motion, but it must be adjusted properly for the conditions (see “Tools to Tame the Jibe” ). You can raise the aft end of the boom simply by ordering a sail with a higher clew. A helmet can help on smaller boats, protecting against minor boom nicks, companionway bumps, and just plain falling down, but not so much with solid boom impacts (see “Protecting the Sailor’s Pumpkin”). I’ve been known to wear a helmet in blustery conditions, specifically when singlehanding. I’ve seen padded booms. I suspect it helps, but it makes the boom bigger, and like a helmet, it won’t prevent neck injuries or violent jibes that knock sailors off the boat.

TRAVELLER

The traveller is also responsible for MOBs and fatalities. Putting the traveller on the cabin top or back of cockpit, rather than in the middle of the cockpit, can help avoid trouble, but we don’t recommend moving the mainsheet and traveller out of the helmsman’s easy reach, especially for shorthanded crews. The Clipper Race now marks the danger area with bright tape. Locking the traveller down (both sides) after jibes helps. Twin mainsheets (“Do Twin Mainsheets Better control the Mainsail”) can eliminate the traveller, but these introduce some added cockpit spaghetti and the mainsheet can still whip across with lethal effect.

WINCH HANDLE HOLDERS

Winch handle holders don’t seem like a safety item, but I watched someone slide overboard as he lunged for a run-away handle. Anything that reduces unplanned movement will reduce accidents. Some racers cover the handles with Velcro and just slap them on a cockpit bulkhead. There should be a holder near every winch. If you have winches on the mast, keep a handle there; you need both hands free when climbing forward to reef or furl—one hand for the ship, one hand for yourself.

TRAMP LACING

Racing’s governing body, World Sailing, states tramps must be “made from durable woven webbing, water permeable fabric, or mesh with openings not larger than 5 cm (2 inches) in any dimension. Attachment points shall be planned to avoid chafe. The junction between a net and a boat shall present no risk of foot trapping.” Nevertheless, we’ve seen enormous gaps in corners on brand new boats. Corsairs often have a big gap near the center hull to allow for folding. I’ve gone through that hole one a few times, past the knee. I filled the gap with a mini-tramp.

ADD MORE NON-SKID

Some makers don’t understand that when a boat heels, the deck changes. Sloped cabin trunks can become deck. Areas previously inaccessible seem like logical foot placements. And then there are the sloped areas that should be avoided, but in the heat of the moment, you’ll put a foot there anyway. I’ve added non-skid to sloped cabin trunks, saving quite a few slips. Hatches present a dilemma. Walking on them will add wear and tear and is not recommended, but hatches near the mast and in high traffic areas will attract the occasional stray foot. The ISO 15085 standard specifies that there be no gaps in non-skid greater than 3 inches on working deck areas, though it allows 20 inches (500 mm) for glazed areas (hatches).

WAX

I’d much rather have dull gelcoat than an ice rink. As for non-skid waxes, such as Woody Wax? Not worth the trouble in my opinion. (see “Nonskid Waxes”).

SLIPPERY STEP NON-SKID

Often the non-skid tape ends an inch back from the edge of a step because it looks better. This makes no sense from a safety standpoint. The non-skid should wrap right around the front of the step, since that’s where your foot often lands when you misstep. Add more grip tape, if needed. I’ve skidded off too many slippery steps.

SLIPPERY HATCHES

The insistence on clear hatches everywhere is unnerving. If you don’t need light below, what’s wrong with an FRP hatch painted with non-skid? It seems an obvious failure in design to place a hatch that cannot withstand light foot traffic in a location where routine tasks are carried out on deck. Some boats have clear hatches over anchor wells, sail lockers, and storage lockers. The only way a crew member would be in any of these spaces with the hatch closed is if they were plotting a mutiny. I’ve painted these hatches black and added non-skid. When I reglazed them, I replaced the acrylic with fiberglass and non-skid.

AREAS OF EXCESSIVE SLOPE

The ISO 15085 standards limit any slope on the deck to 15 degrees before heeling. You can’t eliminate these slippery slopes, but you can add more aggressive non-skid, such as grip tape, and use a contrasting color to make the danger more obvious.

OBSTACLES AND STEPS

No obstacle or step should be over 20 inches (0.5 m) per ISO 15085. As a rule, cockpit benches and traveler horses are lower than that. However, a standard step is just 7.5 inches and you should consider adding steps where this is not the case. We added a removable step inside our F-24 because the factory step-down (16 inches) was causing missteps, knee strain, and bumped noggins.

STANCHIONS AND LIFELINES

Are the stanchions and lifelines sturdy? Testing by the U.S. Naval Academy demonstrated that many pulpits on recreational boats are not built to withstand the loads of a falling body (or two) on the lifeline. In more than one of the Academy tests, the impact of a falling body ripped out poorly reinforced stern rails. Stanchions should withstand 63 pounds of force (0.25 KN) with no more than 2.4 inches (6 cm) deflection.

TETHERS AND JACKLINES

A quick search of our archives will uncover more than a dozen articles on safety tethers, harnesses, fixed clip-in points and jacklines. Clip-in points for safety tethers should be located within.

• 1 meter of companionway,

• 2 meters of helm,

• 2 meters of mast,

• 2 meters of winch, and

• 3 meters anywhere on deck.

Don’t forget that jacklines and stays can serve as handholds forward of the mast—one more reason to rig permanent jacklines even for inshore boats. Clipping points must hold 1,350 pounds (6 KN) minimum, and jacklines and their attachment points must hold 4,500 pounds (breaking strength, not working load). We’d argue for a 4,500-pound (20 KN) breaking strength for all clip-in points, since that is well tested in climbing and the hardware is readily available.

DECK SHOES

Footwear should be optimized for both wet and dry traction. Aggressive soles, such as trail-running shoes, can grab lines and increase foot tangles. Some folks swear by wearing their deck shoes only when they are on the boat, but I’ve always found that a certain number of concrete miles wears off the dead rubber and maintains the traction. I like Sperry, but the grip fades after three seasons max. Retire your deckshoes to around-town wear when they get slick, not when they wear out. (See “2007 Mens Athletic-Style Boat Shoe Test,” “Sailing Shoe Test Update,” August 2014, and other PS reviews.)

TOERAIL

Too many small boats lack or have inadequate toerails. World Sailing’s only requirement is for a toerail forward of the mast, and the required minimum height is only one-inch. In our view, anything less than 40 mm (1 ½ inches) makes a lousy foothold and won’t reliably catch a sliding boot. Two inches is better.

From ISO 15085:

Category C [near shore] sailing boats: the footstop height is 25 mm (1-inch).

Category A and B sailing boats [offshore]: the footstop height is 30 mm (1 3/16 inches).

Gaps for drainage and around fittings must not exceed 100 mm (4 inches).

HANDHOLDS

Always keeping “one hand for yourself” keeps you on the boat, so long as there is something reliable to hold onto. You should be able to move from one secure hold to the next from bow to stern; ISO 15085 sets the maximum spacing at 4.5 feet (1.5 m). Consider wrapping slippery stainless bars with small line or leather to improve grip. Add handholds anyplace that feels insecure. ISO 15085 says handholds must hold 340 pounds (1.5 KN), but ideally, they should be strong enough to clip into (4500 pounds breaking strength required), but greater than 1,200 pounds (5.5 KN) and unbreakable with a strong kick is a good starting point.

Handholds are particularly important entering the cockpit and anywhere the deck slopes. We’ve even added extra stays near the mast, both to deflect sheets away from mast-mounted winches and to serve as sissy holds and vertical jacklines when working at the mast.

Lifelines should not be used as handholds. Repeated yanking will probably loosen the bedding, resulting in leaks and possibly core damage. They also put you a little too close to the edge on the windward side and way too close on the leeward side.

GLOVES

Like deck shoes, gloves offer increased grip and prevent injury and resultant accidental release when you grab thin steel cable or something sharp. We consider them part of our safety kit when going forward in a blow. (See “Winter Glove Report” for our latest update of Gill sailing gloves.)

BOARDING LADDERS

For all but the smallest boats (freeboard less than 20 inches/0.5 meters) ISO 15085 states the boat must have a “means of reboarding” which “must be readily accessible and usable, when in place, without assistance from anyone on board.” This should be a fixed boarding ladder, which can be deployed by a swimmer. The lowest ladder step must be 11 inches below water. The American Boat and Yacht Council recommends 21 inches, and we concur (see “Practical Boarding Ladders”).

HATCHES

Openings over 3 feet deep must have cover, guardrail or net. More than a few sailors have tumbled down an open companionway slider, sometimes breaking bones and seldom without serious harm. Deck hatches are another hazard, though less damaging. Smart practice is to close the slider and hatches once the boat starts heeling.

SLIDING CUSHIONS

Cushions love to slide when you step on them returning to the cockpit. Secure them on the outboard, not the midships side. I’ve seen the reverse on factory jobs, and it is unsafe, since they will still slide when heeled. Ties or buckles are preferred over snaps, which either fail or seize. Velcro is not enough.

LINES UNDER FOOT

Lines that run athwartships will trip you and those running parallel to the rail will roll underfoot like marbles. Route them next to cabin walls and in non-traffic areas as much as possible. Sometimes a bungee cord can control slack.

Multihull and sport boat owners should consider running lines under the deck or trampoline where possible. Likely candidates are rig tensioning adjustments and barber haulers.

Organize the tails after every maneuver; not necessarily coiled, but straightened up. Sheet bags can help.

SHEET TAILS

A running sheet wrapped around your leg can throw you overboard. The old saw that “mainsheet men hop on one leg” contains a kernel of truth. The clearest example for me was testing drogues and sea anchors at speed. When first deployed , the rope only played out at 5 to 14 knots, but it was not going to stop, even if it had to break me in half and drag me through the stern rail with it.

LIFELINES THAT GO SLACK

On many lifelines, if a gate is open the entire side is slack. If someone tries to catch their balance on a loose line, a nasty tumble can result. I took a stanchion tip to the rotator cuff that way once. The solution is simple, add a clamp or lashing to keep the line from sliding through the stanchions when the gate is unlatched.

BRACING IN THE COCKPIT

Foot braces aren’t necessary to keep you from falling, but you’ll need them to be able to do your job during a knockdown or broach. The boat heaves and suddenly the trimmers are off station, unable to release the line they were assigned to watch. Or perhaps they cling tight to the rope, unable to let go because either physically or psychologically, it is the only thing securing them to the boat. For the helmsman, a foot brace is part of the answer. Work station tethers, positioned just so and of the right length, can also keep you in place. Finally, have the forethought to brace properly in rough conditions, anticipating the forces that extreme heeling and rapid deceleration will bring.

POOR LIGHTING

Spreader lights rarely provide enough illumination for close work in all areas of the deck. To compensate for gaps or shadows, install fixed white and red lights in the cockpit and white lights at the bow and in the anchor locker to illuminate activities like lashing down an anchor or setting a storm jib. Head lamps can fill in, but are not a complete replacement. (See “Are Chart Lights Steering Us Wrong?”).

SHEET SNAGGERS

Anything that can cause a hang-up mid tack or jibe could cause serious trouble short tacking in a breeze. This is not something that only affects racers, since it often requires that someone to run forward at a dangerous time. Mast-mounted winches are handy for hoisting and reefing, but unless they are well guarded, they can catch sheets on every tack. Ventilating cowls and heater stacks can be a problem. Don’t curse when a sheet snags. Solve the problem with guard rails and deflectors, removing the offending item, or by modifying your sheets for easy tacking (see “Webbing Uses for Sailors”).

DINGHY ON DECK

Davits don’t work on every boat. They can make a boat vulnerable in a following sea and increasing weather helm. However, a dinghy on deck is often in the way. Stowed on the bow, it can increase yawing at anchor. It can also interfere with movement on deck. Often, it blocks emergency exit via bow hatch, critical in the event of fire. If you opt for a deck mounted dinghy, strong lashing points are essential. By adding loops to these tie-downs, you can turn a deck-mounted dinghy into another place to grab on.

DANGEROUS SWITCHES

My closest brush with serious injury happened during a routine fair weather anchoring. I was kneeling on my right knee with the windlass foot switch to my left. I was pressing the switch with my left hand, preparing to recover the snubber. An unexpected wake threw me off balance, my hand landed on the chain and my left knee on the “up” button. I didn’t want to press down hard enough with my hand to unweight my knee, because my hand was sliding towards the gypsy. I couldn’t get my knee off the switch because most of my weight was on it, with me leaning into the lifeline. The whole incident lasted only a second, but I could easily have lost a finger and only a stout leather sailing glove saved me from serious harm. From then on I always either sat or kneeled on both knees. Going forward, only hand switches for me.

DINGHY BOARDING

Sugar scoop transoms can make the transfer from dinghy to mothership safer for the less athletic sailors. The ABYC requires two full steps underwater, the lowest at least 22 inches. Three steps (34 inches) are better. (See “A Stern Look at Boat Sterns“).

DOWN BELOW

The same principles apply as on deck. The companionway steps are probably the leading hazard. Be generous with non-skid (see “Finishing the Cabin Sole”), the grab rails must be continuous, and the steps should have end stops so that they are safe when heeled. Two handholds must always be within reach. No sharp corners on cabinets, no gloss varnished floors.

CONCLUSION

A safe sailor is constantly evaluating the safety of their boat and practices. You don’t need to be Captain Safety, strapping more gadgets to the boat to make it safe. Instead, focus on making it safe to work and move around the boat. As we get older and smarter, we get fewer bruises and “boat bites.”

Poor footing has been the instigating factor in many accidents at sea. Slippery decks are part of the problem, but in many cases, the danger is due to poor layout or design details.

NON-SKID

1. Many sailors think they’ll never tread on the sloped sections of their cabin top, until they slip. These elevated spots on the coach roof are some of the most vulnerable places and care is needed where the transition from deck level to cabin top or vice versa. We try to spend as little time on the cabin top as possible as it puts us in the perfect position to be pitched over the lifelines. Here we put non-skid tape on a sloped area of the hull that needed it badly.

2. This narrow strip of nonskid offers little security on the narrow curved area of the hull. This is a prime candidate for additional protection with more tape or non-skid.

SHEETS AND LINES

3. There’s not a whole lot you can do to reroute jib sheets while you’re sailing. If you are on a long tack you might be able to rearrange the lazy sheet to allow for a better pathway fore and aft on the windward (high) side deck.

TRAMPOLINE GAPS

4. Trampoline gaps can be a leg or knee-cap breaker. This one caused some serious pain to Practical Sailor Tech Editor Drew Frye, who fell in up to his hip and planted his knee cap firmly on that hinge. He later filled the gap with a mini-tramp.

COMPANIONWAYS

5. Non-skid tape is your friend on stairs. This step near the cockpit inevitably gets wet. Instead of ending the tape near the edge of the step, it should wrap around the edge.

6. If a hatch is near where crew are normally standing—in this place the mast—it should be assumed that someone will eventually stand on it. We used Outland Hatch Covers on some of our hatches, and made our own snap-on hatch covers for other hatches (see “DIY Fiberglass Hatch CoversDIY Fiberglass Hatch Covers,” March 2016.

An easy first step to improving safety on deck is to clean up the cockpit and foredeck. Here are a few bins, bags, and widget-grabbers that we’ve come across in our quest for an uncluttered space to carry out the business of sailing. If you are new to a boat, we suggest you live with the clutter a bit until you sort out exactly what you need and where you need it.

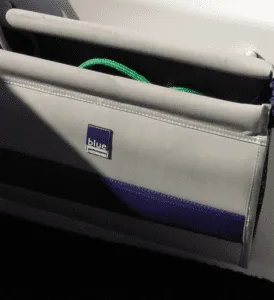

WINCH HANDLE STOWAGE

1. The Blue Performance winch handle bag can be conveniently mounted on a cockpit bulkhead. Leaving the handles exposed runs the risk of a snagging lines.

2. Stick-on hook-and-loop fasteners require no drilling

LINE STOWAGE

3. Running the barber hauler under the deck clears deck space.

4. A “cat-bag” can be used to catch an all rode anchor rode, or the stern rode for a drogue, kedge, or shore-tie.

SHEET BAGS

5. The Blue Performance sheet bag is a convenient catch-all for sheets and halyards led back to the cockpit.

6. Mesh speed up drying and let you see what is inside. Many sheet bags have side pockets for water bottles or winch handles.

Every boat is different. Some have clear side decks fore-and-aft, others have narrow passages forward. Some cockpits are so broad you need footholds to stay in seated in place, some small cockpits offer little more than a footwell—and very little room to slide about.

The same goes for sailors. You know your own physical limitations, and hopefully, those of your crew. While the more limber ones might spring out of the cockpit without a problem, others may have to develop a routine for exiting the cockpit using multiple handholds.

1. Tech editor Drew Frye designed his own tether. It has two legs allowing him to always stay connected as he transitions from one clip in point to another.

2. Noted single-handed offshore sailor Skip Allen likes to double up his 6-foot tether around the jackline when working forward. The alternative is a two-legged tether with a shorter leg that is used for foredeck work.

3. A simple, adjustable noose (aka whoopie sling) in this Dyneema lifeline can be tighted in an instant, ensuring protection from going overboard where previously there was none. (See “Slick Whoopie Slings for Sailors,” PS April 2021)

For a complete look at Practical Sailor’s research into these and related areas the ebook “Man Overboard and Prevention,” covers it all. https://www.practical-sailor.com/product/mob-prevention-recovery

This article was originally published on June 14, 2022 and has been updated.

This is one of the most comprehensive articles on sailboat safety I have read, it incorporates all of the many areas on a sailboat where Murphies Law is hard at work. It always pays to carefully look around when you get on a new boat to check for potentially hazardous areas. Go up and down the companionway and wander up to the fore deck to check it out, take a look at the sheet and halyard leads. I especially appreciate the discussion on how to move about on a sailboat, I always tell new crew, to think turtle not antelope, it may be hard on your knees but it’s safe and quite in harmony with a good sailing experience.