This summer is shaping up to be a strange one—a pandemic moving through the land and an economy reeling from its strains. And now protests in the streets. A very strange summer indeed.

It is enough to make any sailor long for a return to the sea, to solitude, to the world we know best, where wind and waves are the most we have to fear. For the sailor at sea there is plenty of mystery, but very few unknowns.

But how do we get there?

We’ll not pretend that the average Practical Sailor reader is a 20-something just out of college dreaming of buying a boat. That was me, a long time ago, and it was a good 20 years before I found Practical Sailor (too late to spare me too many troubles). I learned most things the hard way, and relied heavily on the wisdom of those who knew better than me. And now those wise and generous sailors are old, quite old. (Some of them, sadly, have died.)

They are in their homes with their families, keeping the company of a few friends, shopping during off-peak hours. They struggle with the usual ailments that come with age. In normal times, our infirmities are a nuisance, a burden that is oddly comforting, because we know that we are not alone. But these are not normal times. Some of my friends, once avid sailors, are reluctantly selling their boats. It is just too much trouble, they say.

And this is sad, because we will all be safer on the water this summer. But getting there will be easier for some of us than others, and hopefully the sailing community will recognize this. We’ll understand why some of our oldest sailors might feel uncomfortable in a crowded skippers meeting, and would rather go through the routine virtually from home. We’ll understand why our neighbor would ask if we could air out his boat in the yard. And why he won’t be launching this year.

For the high risk among us who’d rather not tempt a terrible end, it’s a comfort to know that there are sailors who will understand and support them.

If you know an old sailor reach out to them. Ask them what they need. Bring them a beer (or hot tea, as some have oddly sworn off the stuff). Listen to their tales, no matter how many times they’ve been told. Take them out for a sail.

And if you sense that this isn’t enough. That there’s clearly still something missing from their lives—the whir of a grinder, the smell of fresh varnish, the taste of whipping twine (for who can thread sailmaker’s needle without a good wet lick?)—then here’s what I recommend.

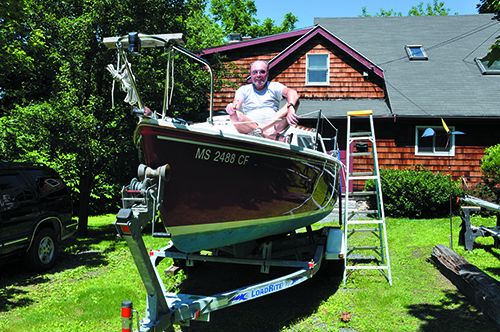

Take up a small collection and buy the nearest weather-beaten Catalina 22. Plop it down in their driveway, set up a ladder, and let them have at it. They’ll be happy and busy all year. And probably the next. And maybe the next.

Although far from perfect, the C22 has just enough virtues to make its vices worth the trouble. Thanks to an extremely supportive owners association, there really isn’t anything that can’t be fixed on these boats (though the iron keel can be a bear). And when everything is fixed, boy are they fun to sail. It’s almost as if the boat was designed to be a gateway for the other plague—the contagious dream of escape.

Of course, there is a caveat. This could just be my own delusion. You see, there is a C22 in my driveway, begging for attention. It has been that way for years.

So don’t worry about us. We’ll have plenty to do this summer. But we do worry about you. Stay safe.