300

The tragedy in this year’s Chicago-Mackinac Race offers compelling evidence that it is time to rethink the current recommendations for safety-tether design and use. When the Kiwi 35 WingNuts capsized in a storm that struck during the race, two of the sailors aboard needed a knife to cut their tethers and be free of the overturned boat. A third needed help unclipping. Two other sailors died, with their tethers still attached to the boat.

Similar accidents, recent product recalls, and findings in Practical Sailor’s latest round of tether testing also bolster the argument that sailors—and manufacturers—need to pay more attention to the safety tethers on the market today.

The safety tether is the sailor’s leash—a short stretch of webbing or rope that keeps a sailor from going overboard. Its purpose is complicated by the fact that it must be capable of two opposing functions: It must offer a secure means of attachment to the boat, and, when the need arises, provide a quick means of release.

The typical, single-leg safety line has three main parts: the tether, usually about 6 feet of webbing; the jackline hook, a hook or clip that the sailor attaches to a fixed point or jackline on deck; and the harness clip, a quick-release hook that connects to the sailor’s harness. Some tethers have a simple loop in lieu of a harness clip. The loop is spliced to the harness or attached using a cow-hitch, the same knot commonly used to attach name tags to airplane luggage.

In order to comply with tether recommendations for offshore racing—as set forth in the “International Sailing Federation’s Offshore Special Regulations Governing Offshore Racing for Monohulls & Multihulls”—safety lines should meet the following requirements:

• The length should be no more than 6 feet in length.

• A tether purchased after 2001 should have a colored flag embedded in the stitching to indicate overload.

• Any hooks or clips should be self closing, designed so that they cannot accidentally unclip.

• Hooks and clips should be made of materials that won’t interfere with a magnetic compass.

• In the U.S., the tether should be a January 2001 model or newer.

• The tether should be able to withstand drop tests using a 220-pound test dummy from 6 feet.

Although the Special Regulations strongly recommends that safety clips be easily released under load, it is not required.

300

Many of the above engineering details are spelled out in IS0 12401, or EN 1095, the international standards for safety lines upon which the ISAF standards are based.

268

The Snap Shackle Trend

Our previous reports on safety tethers looked at a range of tethers and offered specific guidance. For this report, we will narrow the lens to examine the snap shackle, which has become the most common hardware for attaching the tether to the user’s harness. For details on the boat-end hooks and clips see “Jackline Hooks”; for a recap of tether materials and design, see “The Sailor’s Leash” . After our experience testing tethers in 2007 and harnesses in 2009, we know that the snap hook is one of the most problematic details in the offshore tether.

During the last two decades, other fatal sailing accidents (see “Tether Incident Reports,” ) have prompted changes to tether designs. One of the most significant changes has been the addition of a quick-release at the harness-end of the tether.

In 1999, all but two of the 18 tethers that Practical Sailor tested had a hook or clip at the harness-end, allowing the sailor to release himself from the boat. Seven used a single-action snap hook, a simple hook with a spring-loaded hinged “gate;” six used a snap shackle, designed to release under load; and two used a locking aluminum carabiner.

Since January 2007, we’ve tested 20 different tethers, and seven of those used a snap shackle at the harness end. Five used the Gibb-style, double-action snap hook. Three tethers used screw-type carabiners; two used single-action snap hooks; and three tethers—two of them for children—used simple loops.

Since 1999, PS has recommended a snap shackle to connect a tether to a harness. A modified version of the Nicro spinnaker shackle used since the 1980s, the snap shackle has a hinged hook secured by a spring-loaded pin. To open, you pull on a lanyard connected to the pin with a split ring, and the loaded gate pops open. This is the only clip or hook used in marine safety lines that we’ve tested that can be released under load.

Our confidence in the snap shackle is not without reservations. In 2007, and again in 2008, testers found that some users were not strong enough to release the shackle under load and that trying to grab hold of the short release lanyard—particularly when it is hidden beneath the bladders of a self-inflating PFD/harness—was difficult. Half of our on-the-water tests in 2008—which involved dragging a “victim” at 4 knots through the water—had to be suspended because the tester could not open the snap shackle.

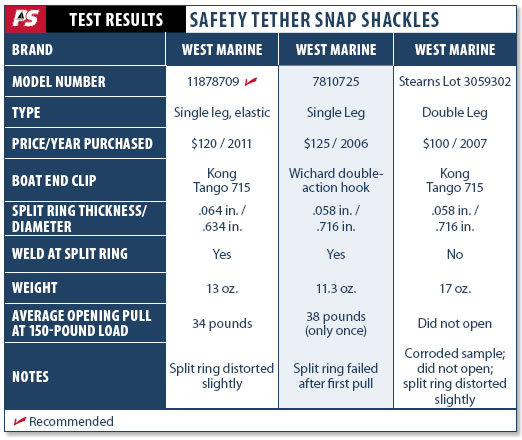

In 2010, in response to a letter written to Practical Sailor regarding a split-ring failure, West Marine voluntarily recalled tethers with split-ring connectors. The split ring now used in West Marine’s tether is a smaller diameter than those in earlier versions. (See table above, “Safety Tether Snap Shackles.”) Soldering where the rings overlap is used to help keep the snap ring from distorting under load.

It is important to note that the problem with split rings is not limited to West Marine tethers. The supplier of the tether, the Italian company Kong, also sold nearly identical tethers to other U.S. retailers such as Defender Industries.

How We Tested

West Marine’s introduction of a new line of tethers with an improved snap-shackle design prompted PS to test them against two of their predecessors, each of which was rated at one time as our Best Choice safety tether. All testing took place at our workshop in Sarasota, Fla.

The test protocol was fairly straightforward. A fixed load was applied to each tether, and the amount of force required to open the snap shackle was recorded using a spring scale attached to the release lanyard. Each snap shackle was tested five times at three different loads: 150 pounds, 250 pounds, and 350 pounds.

The first of the three products tested was the new safety tether introduced by West Marine, its Single ISAF Safety Tether (Model 11878709). This product replaced a safety tether (9553512) that, along with its two-leg version (9553504), was recalled in 2010.

The second tether was a 6-foot blue West Marine tether that we purchased in 2006 and was featured in our 2007 tether test. The tether (7810725) features a Wichard snap hook at the boat end and a snap shackle on the harness-end. The tether lacks an overload indicator, so it does not meet current ISAF standards. The split ring on this tether was electro-welded at one point where the rings overlapped. The tested tether had seen some use, but was well maintained over the past five years and showed no signs of corrosion. This tether was not included in the West Marine recall.

The third tether in this comparison was an ISAF-compliant “double” tether, which was made by Stearns and introduced by West Marine in late 2006. This tether was the first to feature the lightweight, aluminum-alloy Kong Tango 715 clip on the boat-end and an overload-indicating flag sewn into the webbing. The model number is not indicated on the tether, but a according to West Marine, it is 8639320. It varies slightly from West Marine’s recalled tether in that the release lanyard has five small balls on it, while the recalled tether had a fixed loop with a black plastic finger pull. The tether used for this test did not have any visible tack weld on the split ring for the lanyard.

296

For the past five years, this tether has part of a long-term evaluation of the corrosion resistance of the tether’s metal fittings. It was immersed in salt water for four weeks and then put into a storage box where it has remained for the last four years.

One notable product that we did not receive in time for testing this round was the Wichard single tether. Wichard is the only tether brand that we are aware of that uses forged snap shackles. Most stainless-steel snap shackles are investment cast, which means that molten stainless is injected under pressure into a mold, a process that can create cavities or other flaws in the metal. Forged pieces—in which heated or cold metals are hammered into shape—are less prone to these flaws.

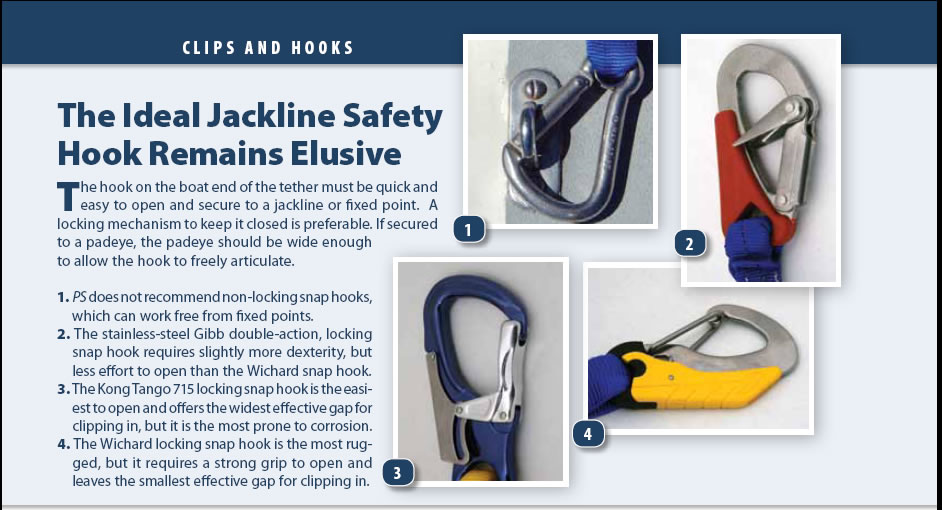

During sea trials in 2009, PS testers found the Wichard locking gate hook at the boat end more difficult to open than others like it. This hook, which is also featured on the boat end of older West Marine and other safety tethers, requires a strong grip to open. (See “Hooks and Clips,” on Right.)

285

West Marine Single ISAF

Safety Tether (11878709)

Even though it has a lightweight, aluminum-alloy Kong hook at the boat end, the West Marine tether weighs a bit more than the earlier model tethers with stainless-steel Gibb or Wichard hooks at the boat end. We attribute the added weight to the 1¼-inch webbing, as opposed to the 1-inch webbing found in earlier models.

The snap shackle, which is manufactured in China by the same company that makes the West Marine harnesses, is more polished and shows better machining than the early version of the ISAF tether. Apart from the tack-welded split ring where the lanyard attaches, the most obvious difference from earlier ISAF tethers is the rounded end of the spring-loaded retaining pin. The pin is clearly more rounded at the end than any of the other tethers in our possession, which may explain its ease of release under load.

This tether was the only one that released more than once under load. However, after the load testing was complete than the snap shackle’s hinged hook was bent. This will not happen under normal use, but our experience emphasizes the importance of checking the gap where the hook seats over the pin. If the retaining pin does not protrude slightly through the hook when the snap shackle is closed, the hook may be bent or the pin spring might be bad. In either case, the snap shackle could accidentally open.

The testers’ main beef with this tether was the looped lanyard. As testers pointed out in the 2007 test, a loop in a lanyard is a bad idea because it can snag on something and cause the tether to open unintentionally. The new finger pull is flatter and less obtrusive than the triangular finger pull used on West’s previous ISAF model, but it can still snag. Also, generating the 30-plus pounds required to open the tether requires a good grip, and getting your fingers into the small loop—particularly under duress—is more difficult than it needs to be. A person wearing gloves or someone with thick fingers could have trouble getting a grip on this lanyard.

Of the three lanyard designs that West has put on the market recently, the 3-inch lanyard with four round balls is the least vulnerable to snagging, but it is hard to grip, particularly if you are wearing gloves.

Bottom line: This tether is a welcome improvement over the previous version, but it is still a work in progress, in our view. The soldered split ring clearly works as designed, showing only a minimum amount of distortion.

West Marine Elastic Single

Safety Tether (7810725)

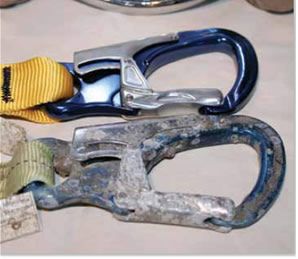

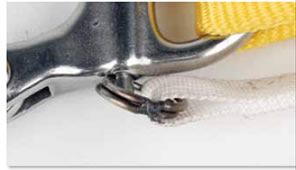

Selected as our Best Choice in 2006, this tether has held up well under light use. The elastic has lost some springiness, but there is no visible corrosion on either the Wichard snap hook or the snap shackle. During testing, however, the snap shackle opened under only the lightest load, 150 pounds. This required 38 pounds of pull, which was enough to break the small electro-weld that held the overlapping rings together. The split ring was distorted so that the lanyard pulled free, and the split ring was no longer usable. (See photo)

Bottom line: This tether serves as a good example of the vulnerability of split rings and the difficulty releasing a snap shackle under load. Even though this split ring was electro-welded, the ring still could not support the 38-pound pull required to open the snap shackle.

West Marine ISAF Double safety Tether (8639320)

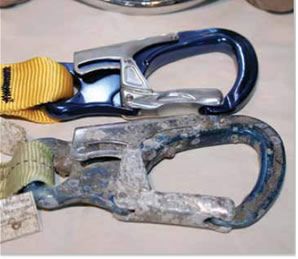

As expected, the anodized aluminum-alloy Kong hook showed significant corrosion after its long saltwater bath—long enough to grow barnacles. Even in this corroded state, the locking mechanism on the dual-action Kong hook continued to work, although it occasionally stuck in the unlocked position. A combination of a weakened spring and corrosion prevented the hook from returning to its locked position, but once the hook was cleaned and lubricated, it continued to work fine. The hook supported 750 pounds of load without any problem; it is rated for far more.

The stainless-steel snap shackle showed a fair amount of corrosion, particularly where the pin locks in place. The spring-loaded pin still snapped into place, keeping the hook securely closed. During load testing, this snap shackle refused to open, even with the lightest load (150 pounds) applied to the tether and maximum pull (50 pounds) applied to the tether release pin.

Interestingly, the split ring, which was not tack welded and had been immersed in salt water for four weeks, was only slightly elongated at the end of several 50-pound pulls. It measured the same size as the ring that elongated during our test, but it appeared to be of a different, shinier metal.

The elastic in this tether was effectively useless. This could be attributed to the two severe drop tests we performed on it in 2007. However, the short life of the elastic in safety tethers is a common complaint among readers.

Bottom line: Our experience with the debut version of West Marine’s ISAF tether illustrates the importance of proper tether maintenance. Aluminum is particularly vulnerable in the marine environment, so the Kong Tango 715 hook needs to be rinsed after exposure to salt water, as does the snap shackle. The strength in the split ring—even without any welding—suggests that there is some significant variation in the strength of split rings used in marine safety tethers—even among split rings of the same size.

298

Conclusion

Our tests show that our concern about split rings, first raised back in 2009, and West Marine’s subsequent recall were not unwarranted.

When subjected to loads of 150 pounds or more, the snap shackles used in older tethers will not open, or are very hard to open. Although a strong person with a powerful grip can generate 60 pounds of pull on a release pin lanyard, 30 pounds of pull is a more reasonable upper limit. Add the distress, disorientation, and exhaustion that accompanies a real emergency, and a person would be lucky to generate even that.

Our tests also pointed out that West Marine’s new tether is a clear improvement over its earlier designs in terms of ease of release. Not only is the snap shackle easier to release, it has also significantly increased the amount of pull the split ring can sustain. However, the beefed-up split ring has not completely solved a key problem with the snap shackle design: When the snap shackle is put under heavy loads, the average person does not have enough strength to open it with a tug on the lanyard. And the welded split ring could invite corrosion or even weaken the split ring over time.

The welded split ring solution seems more like a stop-gap effort than a permanent answer. We were not happy to see that some design features—like a loop in the release lanyard—run contrary to common sense. The inconsistencies in the materials used in the various snap shackles we tested, even when they came from the same source, were also disconcerting. Clearly there are more tethers out on the water with weak split rings that were not covered by West Marine’s voluntary recall.

So what is the solution? In our opinion, the snap shackle is a less-than-perfect answer to the challenges faced by a tether-release mechanism. It is the best available option at this time, but we hope that someone will come forward with a better mousetrap, a tether release that is both secure and easy to release under load.

We strongly advocate sailors carry a sharp, one-handed knife on their person at all times—one that could quickly sever a tether in an emergency. However, we are firmly against resorting to a cow-hitch tether or similar design that requires a knife to release. The knife should be the last option, not the first and only.

If you don’t like the idea of a snap shackle, opt for the Gibb-style double-action hook, which, although it cannot be released under load, locks securely and is fairly easy for most sailors to open. A plain, gated snap hook like the drop-forged version from Wichard is even easier to open, but it suffers the same problem as the Gibb in that it can’t be released under load. For those sailors who have snap-shackle tethers, we would advise that they take the following steps to ensure it will release in an emergency:

• Regularly inspect the snap shackle for signs of corrosion or added friction. Keep the hardware clean and operating smoothly. If you use a lubricant, avoid getting any petroleum distillates on the tether webbing itself. Lanolin is a safe lubricant.

• Check that the pull-pin seats completely when the snap shackle is closed. The snap shackle should open smoothly, but not on a hair trigger.

• Check the split ring. If it appears undersized or weakened by corrosion, contact the manufacturer.

• While wearing your harness, put your full body weight on the tether and test the amount of pull required to open your tether.

• If you wear a combination harness-PFD, carry out the pull test with the PFD inflated, making sure it is easy to locate and grab your tether release lanyard with a wet, slippery hand. Repeat this test with gloves, if you commonly wear them.

• If you find you cannot open a smooth-operating snap shackle under load, contact the manufacturer.

Although some of the above problems can be solved by do-it-yourself modifications, it is preferable to follow the manufacturer’s guidance on any upgrades.

Manufacturers themselves need to step up. We would encourage them to pay closer attention to the quality and function of every component in the snap shackle and tether. In some cases, making the snap shackle easier to open might involve only minor modification, such as installing a longer lanyard, perhaps knotted or with a small woven monkey’s fist or toggle at the bottom.

The tether’s primary purpose is to keep you on your boat—and chances are that you will never have to detach yourself in an emergency. Nevertheless, being aware of the shortcomings of modern tether design will make you better prepared in the event the unthinkable happens.