If theres a lesson to be learned about personal rescue lights -the kind you have strapped or pinned to your PFD for when you fall overboard-its this: Only fall overboard on a dark, clear, calm night with no ambient light near the surface of the water. And stay close to the boat.

Truly theres an almost infinite variety of conditions in which we might have to search for someone whos fallen overboard. In any kind of chop (starting at less than a foot), your ability to see any light almost at the surface of the water is diminished greatly. Add inclement weather, lights along a shoreline, flashing navigation lights, your own navigation and search lights, the man overboards position in the water and the direction he’s facing, in any mixture you please, and your difficulties will increase dramatically.

No matter what the Coast Guard requires or manufacturers claim, our tests made it clear to us that the primary role of personal rescue lights-both strobes and fixed lights-is to help you locate and recover someone almost immediately after theyve gone overboard, or, failing that, to help the Coast Guard, who will be looking from a helicopter with their night-vision and thermal-sensing equipment on. In either case, strobes will be much more effective than fixed lights, which, as far as we could tell, might serve best simply to cheer up the person in the water.

What We Tested

We tested seven strobes and three non-flashing lights. The 11th product, Sea Marshalls Personal Rescue Beacon, includes a radio beacon as well as an emergency light (which is actually an illuminated necklace). Most use small batteries. (ACRs RapidFire and HemiLight are made for one- time use; their Lithium batteries cannot be replaced.) You attach most with a Velcro strap, a pin, or a clip. Prices range from $12 (ACR C-Light) to $180 (Personal Rescue Beacon).

The Claims

There are two sets of approvals:

1) Coast Guard-approved Personal Flotation Device Lights: These have to be visible from a distance of 1 nautical mile at night when first activated, and must operate for at least 8 hours.

2) SOLAS Lifejacket Lights:These CG-approved lights are similar to the personal flotation device lights described above, except that theyre required to be used on ships on international voyages, and meet the higher standards of an international treaty, the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) Convention. They have to have an all-around light output of 0.75 candella for 8 hours over a range of operating temperatures.

All of the PFD lights are CG-approved except for ACRs Firefly Plus and Doublefly. These two arent CG-approved because their dual-purposes (strobe and flashlight) are powered by the same battery source, meaning the user is less likely to be aware of the battery life. The ACR HemiLight is a SOLAS-approved life jacket light.

Who failed to live up to the CG standards in our tests? The ACR C-Light and the Fulton 102 were not visible at 1 nautical mile in the two visibility tests we performed. The Forespar RL-2 was not visible at 1 nm in the first test, but we spotted a trace in the second test at the same distance.

The manufacturers go a step further and make visibility claims on product packaging and/advertisements (See chart). For instance, the ACR C-Strobe, C-Light and RapidFire and the Forespar RL-2 claim they can be seen up to 2 miles.

Who failed to live up to their own visibility claims in our tests? All of them.

The First Test

Given the maze of emergency conditions possible, we decided to test a coastwise scenario in which someone might fall overboard near shore, instead of in ideal circumstances like the ones described above. We did the first round of testing at a small local boatyard, which was shut down for the night. The yard lies on a small point at the foot of the channel. Inshore and slightly to the east and west of the boatyard were a few residential lights and, during the 1-1/2 hours of testing, two or three sets of moving headlights. About 200 yards to the east, the town beach had three lights over its deserted parking lot. There were no significant sources of light within roughly 100 yards of either side of the strobes. We turned off the floodlights in the yard.

We used one ramp of a Travel-Lift slip as the testing platform. It had an unobstructed view straight out the channel into Long Island Sound. The weather was clear and chilly (about 45 degrees) with no moon but plenty of stars. The wind was almost calm, with only an occasional whiff of a breeze. Offshore, where the spotters were located, there were 6″ ripples. Visibility was excellent: The Long Island shore, about 12 nautical miles away, was clearly seen.

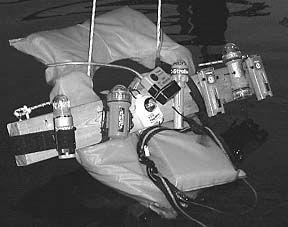

The testing was simple: We fixed all the strobes to a short length of 2×4 and strapped that to a standard Type-II PFD. We suspended the PFD from a loop of line, so that we could lower it from the Travel-Lift ramp to the waters surface but keep the head support elevated 6-8″ in roughly the same position it would be if there were a person in it. In a second position, we raised the assembly two feet off the water, to approximate the height of the strobe if the MOB were holding it up at arms length.

We turned the strobes on, one by one, in a stationary position near shore, and monitored how far they could be seen from a boat moving farther and farther away, with two spotters on board. For this we used Powerboat Reports 21 walkaround.

What We Found

Despite the fact that the local shoreline was not brightly lit relative to most coastal communities, the ambient light was surely a factor in the spotters ability to see the strobes. At a half-mile off shore, the effect was minimal, but as the spotters headed farther offshore, light sources started blending together.

The confusion of light, the increasing distance, and minimal elevation at both strobe and eye levels meant that in those conditions the strobes would be effective only at much closer ranges than we might be led to expect. When the spotters were beyond 1.5 miles away, the person ashore tending the strobes had to flash a 500,000 candella searchlight at them to locate the strobes position. At that point, of course, in an emergency situation, the MOB would not be located. (Note that the spotters were searching with naked eye alone. Neither requires eyeglasses.)

Once the spotters had the test position in view, some strobes fared better than others, and these, it seemed to both spotters and strobe-tender, were simply brighter and more intense than the others. The three non-flashing lights-the ACR C-Light, the Fulton 102 and Personal Rescue Beacon-were not visible at any distance tested.

The Second Test

The results of our first test were so out of line with what wed been led to expect that we decided to do a 180 and test again: We sent the Powerboat Reports editor out in his boat with the strobe lights, while two other editors remained on an isolated sandy spit of the Long Island Sound shore. This time, conditions werent as benign: There was a cold wind out of the west at 10-15 knots, creating a chop of 1 to 2 feet offshore. However, visibility was good. Long Island, about 8 miles south of the spit, was clearly seen. A few blinking navigation aids and the lights of a passing barge or two provided the only ambient light.

The PBR editor first anchored his boat about 1 nautical mile from the onshore spotters (he used a GPS to measure distance) and then 1.5 nautical miles away. As was done in the first test, the lights were attached to a Type II PFD and placed at water level. They were turned on one-by-one. A cell phone was used to communicate with the spotters on shore.

What We Found

Essentially, we had the same results. The lights started out OK, with our on-shore spotters picking up six of the lights (they were either weak or they saw just a trace of the light) at 1 nm. But once the boat moved to the 1.5 nm mark, the spotters saw only one light-and just a trace of it (the ACR Doublefly). Again, the three non-flashing lights were not visible at any distance tested.

In the first test, the Fulton 103 was clearly the brightest light. It was seen up to 1.5 nautical miles, and we picked up a trace at 2 nautical miles. The ACR C-Strobe was weak at 1.5 nm, and we saw a trace of the ACR RapidFire at the same distance. In the second test, five of the lights were visible at 1 nm, but only the ACR Doublefly was visible at 1.5 nm.

So the Fulton 103 and the ACR Doublefly fared best in our visibility tests. Wed give the edge to the latter since it was tested in rougher sea conditions.

Click here to view the Strobe Lights Visibility Tests.

Other Factors

We submerged the lights in salt water for more than 8 hours to test for water resistance and longevity. All remained illuminated for the CG-required 8 hours. The Forespar RL-2 stayed lit the longest, giving out in its 27th hour. At 24 hours, the ACR C-Light was still on but weak, as was the Fulton 102. Only the Fulton 103 and the Forespar RL-2 showed traces of water during our inspection of their innards. They continued to work, though.

Our submersion test also told us this: Only three of the 11 lights float-the Firefly Plus, the RapidFire and the Personal Rescue Beacon.

Easy operation of an overboard light is critical. The person in the water will be scared, if not panicked, and possibly injured after falling overboard. It takes two hands to activate the switches on the round lights, while the ACR Firefly2 and Doublefly have slide-type switches that can be activated easily with one hand (the units themselves are less cumbersome, too). The ACR RapidFire is easily activated by pulling out a pin, and when its properly attached to an automatic inflatable, the RapidFire will activate automatically when this type of PFD inflates. (We tested it and it worked.) We also like this unit because it floats.

Conclusion/Recommendations

Our tests were forgiving in terms of weather, sea conditions, and ambient light. Our observers knew what they were looking for and where the lights were supposed to be-and yet still had trouble seeing them.

No matter who requires or claims what, these lights are best suited for helping make a quick recovery in dark conditions. The greater the man overboards separation from the boat, the faster his or her chances dwindle, so a light attached to the PFD can make all the difference between life and death. For this reason we heartily endorse the use of personal strobes; we just wouldnt count on seeing any of them beyond a half-mile in most conditions. We wouldnt rely on steady lights at all.

If you plan on attaching a light to an automatic inflatable PFD, wed recommend the $41 RapidFire. If youre buying just one light to equip a vest or harness to take with you from boat to boat, the expensive ACR Doublefly (at $109) is a good choice: It performed the best in our rough-water visibility test, and its easily turned on. The $45 Fulton 103, which did so well in our first visibility test, is also a good all-around choice.

Contacts – ACR, 5757 Ravenswood Rd., Fort Lauderdale, FL 33312; 954/981-3333, www.acrelectronics.com. Forespar Products, Inc., 22322 Gilberto, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA 92688; 949/858-8820. Fulton Industries, 135 E. Linfoot St., P.O. Box 377, Wauseon, Ohio 43567; 800/537-5012, www.fultonindoh.com. Sea Marshall Rescue Systems USA, 1411 Broadway Ave., 12th floor, NY, NY 10018; 800/313-9714, www.seamarshallrescue.com.

Also With This Article

Click here to view the Strobe Lights Visibility Tests.

Click here to view the Personal Strobe Lights Value Guide.

Click here to view “The Story Behind the Claims.”

Click here to view the ACR Lights.

Click here to view the Forespar, Fulton & Sea Marshall Lights.