In mid-October, Calypso and her crew were resting in the luxury of Raffles Marina on the western edge of Singapore. A half-mile to the west of us across a river lies the mangrove-fringed coast of Malaysia, our next destination. A few miles to the south, we see the islands of Indonesia just across the Singapore Strait.

Getting from Australia to Singapore was not exactly idyllic cruising. We crossed four seas—the Arafura, Timor, Java, South China—in four weeks.

Entering the transition period from the southwest to the northeast monsoons, the winds proved light and fickle, and we motored almost a third of the 1,000-mile distance from Darwin, Australia, to Bali, Indonesia. On this passage, we got our first exposure to the biggest hazard to navigation for yachts in Southeast Asia: fishing boats.

Fishing boats in this part of the world run the gamut from tiny sail-powered one-man outrigger canoes to huge Japanese and Korean offshore longliners setting mile after mile of lines, often marked by floating radio transmitters and flashing lights.

In many ways, the big fishing boats are easier to deal with. They behave reasonably predictably when setting or hauling, and they use conventional running lights-provided you can pick the running lights out of the maze of deck lights usually shown.

Smaller Indonesian and Malaysian craft (and by smaller we mean everything from 15′ outriggers to 90′ wooden longliners or trap fishermen) use no running lights at all. Larger boats often have deck lights, but they give you no clue as to their direction of travel. Smaller boats are often completely unlit, at most showing a small lantern if collision appears imminent. The smaller wooden boats generally give very poor radar returns until you’re right on top of them, and even larger craft may only show up at a mile of less.

It is not relaxed passagemaking, particularly at night.

When you add on top of this the real or imagined threat of piracy in these waters, you can see why we—and other boats traversing this area—are perpetually on edge.

With the wind well aft when it finally filled in on the passage to Bali, we used our normal downwind rig of mainsail vanged out and down on one side, and the genoa bar-taut on the long spinnaker pole on the other side. We have learned to nail the sails and spars down tightly on this point of sail to reduce chafe, which is far worse in downwind sailing than at any other angle. Another boat traveling the same route at the same time chafed through two spinnaker halyards in just three days.

Spinnaker halyards on in-mast sheaves are particularly vulnerable in these conditions. Both our spinnaker halyards are led over external crane-mounted swiveling Harken blocks, and the halyards show little signs of wear at the sheave after three years of use. Of course, the sheaves and blocks must be clean, undamaged, and free to rotate, or chafe will occur even if the leads are perfect.

Very, very few cruisers are tuned in to the condition of their running rigging. Time and time again, we see boats chafing or breaking sheets and halyards, almost always from a combination of neglect, bad leads, and poorly maintained blocks. Even high-tech cordage does not last forever.

Most people are reluctant to throw away “perfectly good” five-year-old halyards with only a “few thousand miles” on them. The tail end of the halyard may still be fine, but the business end is often stretched to half its diameter and hard as a rock, sure signs that replacement is past due.

In Bali, we gave our old halyards, kept as spares, to the boat with the broken halyards, as cordage suitable for halyards is non-existent in that part of the world.

Indonesia

We entered Indonesia at Benoa, Bali. In this bustling, dirty, commercial harbor, we got a firsthand look at most of the larger types of native fishing and trading boats that we had dodged offshore. Many of the boats looked like abandoned derelicts, and we were astonished to see some of the worst of the lot put to sea to go back to work.

After a few days at anchor among fishing boats and freighters in the main harbor, we shifted to a dock space at the marina.

Yachts here cluster around the Bali International Marina in one corner of the harbor. That part of the harbor also happens to be the shallowest and dirtiest. The marina itself, unfortunately, mirrors its surroundings, with docks slippery with diesel fuel and ground-in garbage. The culprits are local charter boats that refuel daily from jerry jugs, and manage to get only about 80% of their garbage into trash cans. The rest goes onto the dock, or into the water.

Cruising boats go into the marina for security. Long-term anchorage in the commercial harbor has risks, as even the poorest cruiser is rich beyond the wildest imagination of the typical Indonesian fisherman.

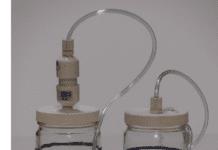

After a week in Bali, we were ready to move on toward Singapore. We were getting low on water; the water in the marina is not potable, and the harbor was far too dirty to consider running our watermaker. Most cruising boats opt to top up with bottled water, but this is expensive and labor-intensive. We chose to get to sea to make our own.

A watermaker gives you a degree of freedom that totally changes your cruising. If we are running in clean seawater we can make water. Our Village Marine Little Wonder still produces just under 6 gallons per hour after three years of hard use. Two hours of operation per day just about keep up with our demands. With the watermaker we do not have to ration water. We don’t waste water, but we do not have to agonize over every drop used, either.

The Road to Singapore

We decided to sail non-stop from Bali to Nongsa Point, Indonesia, which is just across the strait from Singapore. We did this for two reasons.

First, there are tremendous thunderstorms in this part of the world at this time of year. While we were getting ready to leave Bali, a cruising boat was struck by lightning while anchored at the mouth of the Kumai River. Every bit of electronics on the boat was fried. We figured that by minimizing our time in the worst area, we would minimize our risk of lightning strike.

As it was, there were spectacular thunderstorms virtually every night of our passage, but they stayed at a safe distance. During daylight hours there were few thunderstorms, but there were waterspouts to take their place.

The second issue was security. We were sailing alone. The boat we had traveled with from Darwin to Bali broke down near the end of that trip, arriving a day behind us. The same boat suffered another engine breakdown an hour after leaving Bali, and ended up taking two weeks to complete the trip to Singapore under sail. With no engine and very little wind, it was a long, slow slog for them. It was impractical for us to tow them for almost 1,000 miles, so we moved on alone.

Security is a big question in this part of the world. The number of ambiguous encounters with native boats may be small, but the risk is real. Generally, anyone interested in taking your money or your boat is going to check you out during daylight to see how many people are on the boat, even if they decide to strike after dark. We consciously avoided close daylight encounters—under a half mile—whenever possible.

At night, we were unconcerned about brightly lit boats that were obviously fishing…as long as we could stay out of the way of their fishing gear. We were keenly tuned in to smaller boats, whether lit or not, and would make subtle alterations in course to keep from passing closely to them whenever possible.

With our bright steaming light and running lights when under power, they could easily see us, but they couldn’t tell whether we were big or small. They also had no way of knowing that our boat is crewed by two peace-loving people on the far side of 50, rather than a half-dozen well-armed Navy Seals on a rollicking sailing holiday.

We also had the advantage of night vision binoculars and very good conventional binoculars, with just enough moonlight for the night vision glasses to work extremely well.

It is 1,000 miles from Bali to Singapore, and the entire passage takes place in Indonesian waters. You travel through the Java Sea and the South China Sea, two bodies of water that sound a lot more romantic in books than they are in the flesh.

With a full load of fuel—120 gallons in the tank, plus 28 gallons in jerry jugs—we could motor the entire distance if necessary. In fact, we used 90 gallons of fuel between Bali and Singapore, motoring or motorsailing about 650 miles. The sailing was basically downwind, but our zigzag course through the various straits meant a lot of jibing. We also set a course to deliberately avoid areas that a commercial dive operator, who regular moves between Singapore and Bali, had warned us about.

Fortunately, we have finally gotten the jibing routine down to the point where it can be done in a reasonable period of time without undue risk to life and limb. This is only possible because of our Hall Spars carbon pole, which weighs less than half what an aluminum pole of the same length would weigh.

Traffic

The shallow seas of this region—typically under 150 feet in depth—are literally jam-packed with fishing boats and other commercial traffic. Coming around the north end of Bali, we sailed through fleets of hundreds of tiny sailing outrigger canoes, each one trailing one or two handlines. These little boats have inefficient-looking rigs and crude hulls, but they are surprisingly fast both upwind and downwind. Every beach along the north coast of Bali has a large fleet of these boats. When they are all at work, it looks like the world’s biggest Optimist regatta.

Unlike some fishermen, these sailor-fishermen have a keen sense of seamanship. While we tried diligently to stay out of their way, they were good judges of just how much they needed to slow down or speed up to cross our bow or stern. They also realized that their fragile canoes were no match for our 16 tons, and seemed as anxious to stay clear of us as we were to avoid them.

The bigger offshore boats were another story altogether. “Bigger” in this case means anything over 25 feet, whether motorized or sailing. There are still vast numbers of sail-equipped fishing boats in southeast Asia, even though a large percentage also have diesel engines.

By watching the radar during the day we developed a sense of how well—or poorly—different types of small craft would show up. With their low freeboard and rounded wooden hulls, most of these boats are lousy radar targets.

It was impossible to keep count of the number of commercial boats we encountered. There were usually at least a half-dozen in sight at all times, day or night, ranging from small fishing boats to gigantic tankers. We had daily editions of what we refer to as a “Calypso sandwich”: a northbound ship passing us close to one side, while a southbound ship passed on the other side. Without traffic separation zones, you could not really take a course that would guarantee staying with the traffic flow. On more than one occasion, we were surprised to find ship traffic going against the logical pattern, so you could never relax.

Radar

We ran our Furuno 1831 radar constantly. We have had a lot of trouble with this radar, which has been plagued by an intermittent tuning problem for the last three years. Once it tunes, it works fine, but you can never be sure on startup if it’s going to work or not.

Radar is an essential tool in these waters, and the unreliability of our Furuno 1831 simply added to the tension. In New Zealand, we had two technicians from the Furuno agent work on the radar. Each had a different theory, and did a different repair. Neither solved the problem.

In Singapore, Mr. Tang from the local Furuno distributor came to the boat, was able to replicate the problem, and took both scanner and display to his shop for analysis, running them for 48 hours. He decided that the cable was at fault, since he could find no problem with the rest of the system. We are installing a new cable, and sincerely hope Mr. Tang is right. We have now spent almost $1,500 in analysis and repairs on this radar in three different countries.

Singapore

Crossing the Singapore Strait to get from Indonesia to Singapore is similar to crawling across a major freeway on your hands and knees while big trucks take aim at you. With over 200 big deepwater ships passing through the strait daily—plus countless smaller freighters and tankers—this is the busiest stretch of water in the world.

Essentially, you travel parallel to the traffic lanes while waiting for an opening, then dash across to the other side. We found our opening to cross the eastbound lane, seemed to have an upcoming westbound gap, and went for it.

Our westbound gap began to plug with traffic as we struggled at little more than 4 knots against powerful tidal currents with the pedal to the metal. We got across with about 100 yards to spare as a rank of nine ships in three abreast order bore down on us at 12 to 14 knots. We then picked our way through a tanker anchorage packed with more than 100 ships to the peace and calm of Raffles Marina. There is virtually no anchoring for yachts in Singapore except in deep, exposed commercial anchorages.

Singapore is our last chance for major resupply of boat maintenance materials and spares before we reach the Mediterranean some six months and 5,000 miles from now. We have covered 5,500 miles since leaving Auckland in May, and 17,000 miles since leaving Newport three years ago. It’s a small world, but it’s a big world, too.