We never seem to do things the easy way. In late November, Calypso left New England once again, this time bound first to Bermuda, then on to the West Indies. No matter how hard you work and how well you plan, a late fall departure from the East Coast to the Caribbean never seems to get off on schedule.

As you frantically work to get the things done that absolutely must be done, weather windows slip by, potential crews come and go. By the time we pulled out of New England Boatworks in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, just after sunset on November 19, most of the other snowbirds had long since fled south..

After a hectic few weeks, weatherman Bob Rice predicted a narrow weather window opening up, I called our crew to tell him the departure time. To my disbelief, he said that he really didnt have time to do the trip. Stunned, I spent the next two days on the phone, begging friends, casual acquaintances, then professional crewing agents for one or two warm bodies who didnt get seasick and could steer. The weather window disappeared. It began to look like we would never get away.

Why, you may ask, would we need crew for the relatively short 650-mile trip to Bermuda, when we had a capable boat designed to be handled by one or two people? The reason is simple. The North Atlantic in late fall can be a nasty place, with gales that last for days, out-of-season hurricanes, and generally miserable weather. For many of those leaving in 1997, the passages had been bad, with horror stories of broken limbs, gear failures, frantic calls for outside assistance, even a pet dog lost overboard.

For the first 300 miles of the trip, the weather can be bitterly cold-below freezing at night and raw during the day-and cold saps strength quickly. Small failures-a line chafing through, a block breaking, a minor injury in rough seas-can add up quickly to create big problems. Additional crew buys you a margin of safety and comfort for such a trip.

Just when things were looking particularly grim, Dan Keirns walked into the Practical Sailor office, casually opined that he might like to make the trip, and was promptly Shanghaied. Although Dan had limited offshore experience before the trip, he now has plenty. He possesses the critical ingredients for the perfect offshore crew: a cast-iron stomach, an unquenchable sense of humor and a willingness to do anything. He proved a great shipmate.

Although this still left us shorthanded, we were willing to go with only three-provided the weather forecast was reasonably good-when Jim Macfarlan called to say that he thought he could rearrange his schedule to make the trip, if we could wait just a few hours so he could wrap up some business. I would have waited for Jim as long as was necessary.

Jim has been a friend for almost 25 years, but in all that time we had never sailed together. Back in the 1970s, we each owned big wooden boats, and had raced against each other a number of times both inshore and offshore. We kept our boats side-by-side in the same boatyard in the winter. As the former quartermaster of a submarine, Jims love of the sea is at least as strong as mine.

In the mid-1980s, Jim and his wife Suzanne gave up wooden boats, bought a 46′ S&S aluminum ocean racer, Winds Way, and with their two small children, sailed around the world against the prevailing winds. That this family could sail an ocean racer equipped with a huge rig, coffee grinders for trimming sheets, virtually no cockpit protection, and few of the amenities that modern cruisers take for granted, says an awful lot about the Scottish grit of the entire Macfarlan family.

Jim is now president of Sundeer Yachts, builder of light-displacement, long-waterline, offshore cruisers designed to the theories of Steve Dashew. He brings an enormous amount of offshore experience to that job, and will undoubtedly prove a tremendous asset to the company

Trial by Fire and Water

By now, our weather window was more like a tiny crack. A series of fronts was sweeping across the country, low-pressure systems spawned quickly, but it was go now or go never.

After a last talk to the weatherman, we went. We knew it would be rough. Somehow, however, 35 knots seems a lot less menacing on paper than it looks on the ocean.

Over the first 12 hours, light west-to-northwest winds strengthened as a cold front approached. Eighteen hours after leaving, we sped along at 7-1/2 to 8 -1/2 knots before a 30- to 35-knot norwester, down to a double-reefed main and a handkerchief of a headsail. For all but 12 hours of the trip, those two reefs stayed in the main.

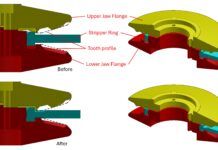

Because this was the first test of our new Whitlock wheel steering system, we steered by hand, trying to get a feel for the changes it brought, desperately hoping that our design, Whitlocks engineering and components, and the installation and fabrication of New England Boatworks would be up to the task.

In strong favorable winds we rolled on: 162 miles in the first 24 hours, 165 in the second.

Herb Hilgenberg, Southbound 2 on the single-sideband radio, was providing weather guidance from Canada for about 20 boats making the transit from the US to the Caribbean, as well as others headed south from Europe. He urged us to get south as fast as possible, as a low sweeping east from the mid-Atlantic coast was going to catch us the next day, bringing strong headwinds. We hurried, but a heavy 40′ sailboat can only make so many miles per day. There was no way we were going to make it far enough south in time to miss the worst of it.

By now confident in the steering system, we engaged Brave Ulysses, the Monitor wind vane, and let him do the hard work. For most of the next three days, Calypso was hard on the wind in near-gale conditions.

On a day race in protected waters, a few hours of winds from 28 to 35 knots can be a lot of fun, with the crew getting soaked on the rail and the boat driving hard. After a hard day race, you head to the bar, proud and swaggering.

The same winds on a passage offshore, however, are different. Seas build quickly to 6 to 8 feet, with far larger waves sneaking in. After several days of this type of sailing, chronic fatigue sets in, chafe becomes a worry. The constant extreme motion both on deck and below makes life miserable, sleep virtually impossible.

The predicted strong southerlies drove us off our course, eventually pushing us more than 75 miles east of the rhumbline to Bermuda. We watched the true wind direction on the B&G constantly, cheering each veering, groaning at each backing. Life on deck was tough, with waves breaking over the boat about once every five minutes. Sargasso weed clogged the bulwarks.

In zero gravity, the life raft leapt clear of its cradle, stretching its hold down straps, shifting some 3″ before settling down, slightly askew.

Life below was equally hard. Occasional dollops of water sneaked through the main Dorades, their drains overwhelmed by near-solid breaking waves. This was solved by turning the big cowls to face aft: we needed some air below, and conditions on deck were very rough but not dangerous. The cowl of the forward, most exposed Dorade had been removed and the box capped before leaving Rhode Island. Previously watertight hatches oozed drips and salt tears rolled along the deckhead from an improperly bedded deck prism.

Maryann struggled through seasickness to try to get us one hot meal a day in conditions that rendered cooking virtually impossible. We lived on Crown Pilot biscuit-the modern successor to ships biscuit, less the weevils. We cracked elbows, hips, heads, all our body parts, against unyielding bits of interior furniture. At least, I thought, the joinerwork is staying put, even if the crew is getting beat up.

Our one failure below was the binocular rack next to the companionway, which accidentally became a handhold in one of those near-knockdowns when wind and wave combined at just the wrong time. At least that bino rack was an off-the-shelf item, literally the only piece of stock joinerwork anywhere on the boat. How dare they make it so weak that a 200-pounder couldnt use it for a grabrail!

North of us, another southbound boat hove to in 40 knots, getting blown back toward the Gulf Stream. Every boat within 150 miles of us reported strong headwinds, and you could read the fatigue through their radio calm.

Its a funny thing, talking on the SSB offshore in heavy going. What you really want to say is, Man, oh, man, when is this going to end? I want out! What you end up reporting calmly, in your best Chuck Yaeger imitation, is, Winds southerly thirty to thirty-five, seas eight to ten, conditions rough, boat and crew doing fine, but we sure would like to buy a wind shift.

You struggle to keep your sense of humor: It must be plain hell ashore on a night like this.

You wish for just a tiny respite so you could get some real sleep rather than a few hours of sleepless half-rest, tensed for the next period of zero gravity, followed by the crash into the trough of the wave behind each rolling blue-gray hill. Please God, let our little boat hold together.

I try to compare it to the other 20 or so trips I have made over this stretch of water, but I can’t. The soothing filter of memory has smoothed those seas, calmed those winds. Surely our trip on Alphida through the Perfect Storm in 1991 was worse, with hurricane-force winds, 45′ seas, and a badly injured skipper. And the long, heavy beat in the 1984 Bermuda Race, with eight of 11 crew comatose with seasickness, must have been nearly this bad.

But those were other peoples boats, other peoples problems. This is my baby getting beat up here, this is a decade of my life on the line, these are my ideas being tested, my workmanship being tried.

Heavy Weather Sailing

We sailed with two reefs and half a genoa, then two reefs and the storm staysail. I came to appreciate the all-inboard configuration of deeply reefed main and storm staysail. A nearly rolled-up genoa may be fine for reaching and running, but it is completely useless for going to windward. The center of effort of the sail is too high, the draft too far aft. In our case, the baggy rolled-up headsail actually created a lee helm.

With the storm staysail, however, the total center of effort of the sailplan is kept lower and further aft, so that the bow is less likely to be knocked downwind by the wave pattern. The hanked-on staysail on a separate inner forestay sets with a more efficient shape, undistorted by rolling around the headstay, and the deeply reefed main interacts better with the staysail than with a scrap of headsail. In addition, the inboard staysail track gives a much tighter sheeting angle, allowing the boat to point better in the lulls between gusts and breaking waves. The chafe of the headsail sheet on the leeward shrouds is also eliminated.

The only downside is that it is very difficult to keep adequate tension on the inner forestay to allow the boat to point. You really need to be able to crank on the running backstays, and our four-part tackle for the runners isn’t really enough purchase for the job.

I had also set the runners on their forward-most padeye, which allows us to short-tack the boat without casting off the leeward runners. I should have led them to the aft offshore position, which gives a better pulling angle against the inner forestay. Conditions were so rough by this time, however, that I did not want to release the runners even for the minute or so it would take to re-lead them aft. The mast was nicely in column, and I intended for it to stay that way.

Although we were hard on the wind, we were not really trying to point. Bringing the bow that close to the wind would have slowed the boat almost to a stop in the 8′ seas. Instead, we sailed at a true wind angle of about 55, bringing it up to about 48 when the sea conditions allowed.

Offshore in heavy going, you sail upwind by boat speed rather than wind angle. In our case, if the upwind speed drops much below 5-1/2 knots, we ease the bow down slightly. If it climbs above 6, and the waves allow, we squeeze up a little.

Calm, then Storm

Our log for this time reads, laconically, southerly gale, and lousy weather.

After 24 hours, the winds eased to 15 to 20 knots and veered into the southwest. We could make good a course due south, which at least meant we were losing less ground. The full main went up for 12 hours, the staysail was put to bed, the genoa rolled out.

It couldnt last, of course. Herb told us it wouldnt. Some 18 hours after the southerly gale petered out, the log reads SW gale 30-38 knots, and we were hard at it again.

In the middle of the night, one of the Monitors Spectra steering lines chafed through at the worst possible spot, which requires hanging over the stern to re-lead and re-tie. We were back to hand steering after two days of letting the vane do all the work. Foolishly, I had underestimated the amount of chafe caused by the conditions. It was one hour on the helm, two hours off for the next 20 hours.

Not long after, the safety tube snapped, due to my own carelessness.When the Spectra line parted, I should have lifted the oar out of the water.

Fortunately, by this time we were only about 100 miles from Bermuda. The needed course, however, was 220. And what was the wind direction? Need you ask?

Now we really did put the boat on the wind, begging for a shift. It came, but slowly. The gusts went from 220 to 240, then 240 to 260. We crawled upwind, needing a big lift.

Instead, we got a painfully slow veering, and only when we were within about 50 miles of Bermuda did it seem like we might make it without tacking. Just at sunset, the wind went firmly northwest, and we had it made. Glancing to windward, we were startled to see Ted Hoods big Robin converging on our course, the now-fair winds encouraging her crew to keep heading south for the Caribbean while we ducked into Bermuda.

Only when there is another boat visible on the ocean can you get a real feel for the conditions, and we watched Robin as she creamed along under a sailplan similar to ours, disappearing behind the waves, then suddenly appearing above as though perched on a small hill. It was like the end of the Bermuda Race, when boats converge on the finish line out of nowhere.

We waved, they waved, then Robin disappeared.Ahead, the loom of Bermuda glowed on the horizon. We were almost home, with only the treacherous reefs and unpredictable currents to deal with.

Five days, three hours after we dropped the lines in Portsmouth, we tied up to the customs dock in St. George,. The wind still howled at 30 knots, but the relatively calm waters of the harbor seemed as smooth as a sheltered marina after the rough open ocean.

Despite never having to tack, almost perpetual headwinds made us carve a huge arcing course in the ocean, adding almost 100 miles to the distance sailed. Our 640-mile course became almost 740 before we finished.

The next day, we motored around to Hamilton-still in 30 knots of wind. At the end of November, Calypso sat on her mooring in Soncy Bay, Bermuda, off Kirk Coopers home Windfall–in a place I had ached to see her for almost a decade. Slowly, the dream was becoming a reality. Calypso had faced her first trial by fire and water, and she had proven herself to be everything we had hoped. With boat and crew a little the worse for wear, we were ready to move on.