The 600 miles of the Malacca Strait between Singapore and Thailand lived up to its reputation as a piece of water to be endured rather than enjoyed. Early winter in the Northern Hemisphere marks the transition between the wet southwest monsoon of summer and the dry northeast monsoon of winter in Southeast Asia, not that there’s any significant temperature difference between “summer” and “winter” here. At this time of year, the region is plagued by thunderstorms and fickle winds, both of which we have seen in abundance.

It also doesn’t help that the Malacca Strait is one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world, and has an astonishing concentration of fishing boats, fish traps, and other hazards ready to entangle the careless or unlucky.

On the way here, we met two boats that got caught up in fish nets. One sailor spent two hours under his boat in scuba gear removing an impossible tangle from the prop. The other was less fortunate, and destroyed a shaft bearing. When last seen, he was sailing to a boatyard in Malaysia for haulout, and hoping that the new bearing he ordered from the US would arrive.

We were luckier with the nets. Despite hitting at least one homemade float marking the end of a drift net, and threading our way through and over mile after mile of nets and pots, we did not snag anything. I put this down to a combination of pure luck and the fact that our prop is nestled in an aperture at the aft end of the keel. Both of the boats that tangled with nets have exposed prop installations. Neither had a line cutting device attached to the prop shaft, which might have saved the day.

Rogues and Rascals

Cruising guides and regional boating magazines are fond of saying that acts of piracy against yachts in Southeast Asia are extremely rare. While this may be statistically correct, it does little to make you feel better. We’ve been travelling through a region with thousands of small boats, often unlit at night. Many of them seem to display an inordinate amount of curiosity about your boat and its crew.

Just before we left Singapore, Malaysian authorities nabbed a gang of Indonesian pirates that had terrorized local fishermen and robbed ships transiting the Malacca Strait. The newspaper reported that at least one more pirate gang was operating in the area.

Sure enough, the night after we anchored off the Water Islands, near Malacca, a gang of 20 pirates in a high-speed boat took over an Australian ship just a few miles from us, while it was running south in the Strait. They locked up the crew (presumably leaving a helmsman and engineer to operate the ship), ransacked the ship, robbed the crew, and fled.

It’s hard to imagine how a boatload full of barefoot pirates in a small boat can even get aboard a big, fast-moving ship, much less take it over. If these guys will rob poor local fishermen—who have virtually nothing to steal—and big ships, would they think twice about attacking two geezers on a 40′ sailboat? We doubt it. Piracy is on everyone’s mind when transiting Southeast Asia, and it should be.

There are also plenty of smugglers, even operating in daytime. In the same general area, our course was crossed by a group of four long, narrow boats operating at high speed, with small deck loads covered by tarps. Atop the deck load of the lead boat sat a man with a walkie-talkie scanning the horizon. The boats passed on either side of us, heading from Indonesia toward Malaysia. We heaved a great sigh of relief as they carried on towards the distant shore.

And why do we think they were smugglers? Each boat was powered by three 200-hp. outboards, which is not a very cost-effective way to move cargo—unless it happens to be very valuable cargo. Over the next few days, we saw several more of groups of boats operating in the same way, always approaching narrow, shallow rivers on the Malaysian shore.

Then we saw the Malaysian authorities patrolling the area. With their deep-draft, medium speed patrol boats about 80′ long, they would be no match for a 40′ boat drawing less than 3′ and pushed by 600 hp.

This is not an area where you want to do a lot of gunkholing on your way north from Singapore, at least not until you reach Thailand.

It’s Alive!

The best news on this trip was that our Furuno 1831 radar now seems to be operating perfectly. Mr. Yang, a Chinese technician in Singapore, correctly diagnosed our intermittent problem as a fault in the signal cable. We installed a new cable and crossed our fingers. We put about 100 hours on the radar between Singapore and Thailand, and it has performed flawlessly.

Given the congestion in these waters, radar is invaluable. Even small, unlit wooden fishing boats tend to show up at a range of about a mile, giving us just enough time to figure out what is going on and take evasive maneuvers if necessary.

Pump Failure

We did not escape unscathed on our trip from Singapore to Thailand. I spent half the night of our approach to Phuket changing engine raw water pumps after a bizarre failure.

In New Zealand, we decided to replace the raw water pump as part of the engine rebuild, keeping the old pump as a spare. The New Zealand Jabsco distributor told us—erroneously, it turns out—that our old pump was no longer made. The pump he supplied as a replacement was quite different, with a coupling that barely engaged with the engine’s pump drive shaft. It worked, however, so we decided we were worrying unnecessarily.

It turned out that we weren’t. Whether through normal wear or some fluke, the pump coupling and drive gear lost their tenuous connection to each other, and we lost cooling water.

For once, however, fortune smiled on us, or was that just a smirk? During our engine rebuild, we had replaced all the hoses in the engine cooling system. In the US, I would have tossed out the old hoses without a thought. With my cruiser’s hoarding mentality, however, I kept the old molded hose bends against the possible rainy day, but stowed them away in an almost impossible location.

A few weeks ago, I ran across the old hoses during a routine reorganization of storage, and shifted them to a more accessible spot. During my emergency change of water pumps, I discovered that the new hoses installed in New Zealand didn’t mate properly with the old water pump, constricting flow. It took only a few minutes to reinstall the 10-year-old hoses, and we had engine cooling once more.

Diagnosing our problem was an interesting exercise. When you lose cooling water, your first two thoughts are that you have sucked something into the water intake, or the impeller has failed.

After an impeller failure (from sucking grass into the raw water intake) a few years ago, we installed a British-made Speedseal pump cover on our engine raw water pump. This quick-release cover gives you access to the impeller in about 10 seconds, without tools. It is so easy to operate that impeller inspections are now a part of the routine engine checklist.

This time, I checked the Groco raw water strainer by shining a flashlight through the clear plastic bowl, finding no obvious problem. A few seconds later, I had the Speedseal cover off, verifying that the impeller was intact. Don’t forget to shut the raw water intake when you do this!

Cracking open the raw water seacock with the Speedseal off, I was able to verify that water was indeed getting to the pump. Now I was confused, as the usual suspects were innocent.

Thinking that I had sucked a plastic bag into the through-hull, and that it had fallen away when I shut the engine down, I reinstalled the Speedseal and restarted the engine.

We still had no cooling water.

In a moment of inspiration, I shut the seacock, removed the Speedseal, and had Maryann crank the engine. The impeller did not rotate in the pump housing. My fear was that either the pump shaft had sheared, or the drive gear in the engine had failed.

It took about two hours to remove the pump, fit the spare pump, sort out the hose connections, and get ready to crank the engine.

All this time, we were hard on the wind in about 18 knots of breeze, sailing at about 6 knots. Maryann was on deck with the binoculars and night vision glasses dodging fishing boats, while I was below with one eye on the radar screen and the other eye on the job at hand. It was not, shall we say, a relaxing evening of offshore sailing.

Miraculously, I managed to change pumps without dropping a single nut or washer in the bilge. It was one of those times when you manage to really, really focus on the job at hand. We started the engine. Few things are sweeter than the sight and sound of cooling water gushing from your engine exhaust.

The Speedseal really made a difference in the time it took to diagnose and fix this problem. If you do not have one on your engine, order it now from True Marine, 30A Merrylands Road, Bookham, KT23 3HW, England, phone or fax 44 1372 451992.

Our failure did not occur when we were motoring, but during routine battery charging at sea. I shudder to think of all the seriously bad times this could have happened. A few hours later, for example, we were motoring 2 miles up a tidal creek to a boatyard nestled in a mangrove swamp. With 8′ of water at high tide—and a 10′ tidal range—we could have been in serious trouble without our engine, and we might still be high and dry in the mangroves, reduced to bones by ravenous mosquitoes.

If we had to have a pump failure—and I’m not quite sure why we had to—it turned out to have been in almost the best possible circumstances.

Alarms

And why, you might ask, do we not have engine alarms to warn us of cooling water loss? The problem is that our engine is not grounded through the block, and requires two-wire senders and switches. These are not easy to find, even in the US. I promise you, however, that I will never, never have another inboard engine that is not fully alarmed, no matter what it takes to achieve it.

Instead, we have a routine of checking water temperature, cooling water flow, and oil pressure constantly when under power. In this case, that routine probably saved the engine from damage, but an alarm system probably would have given us another couple of minutes of warning.

When things are going well, it is far too easy to get complacent. We had logged about 800 engine hours since leaving New Zealand, with few problems.

The Custom of Customs

Now, however, we have a problem. Our spare water pump is now our primary water pump, and we have no backup. The pump we removed is perfectly good, but it doesn’t work on our engine.

The pump we need is not available in Thailand. In the US, a single phone call would put another one in our hands in 24 hours. It’s not so simple here.

Thailand has no provision for the duty-free transshipment of parts for a yacht in transit, and the Thai customs situation is a nightmare. For example, when we checked into the country, the customs agent charged us about $12 for a non-existent “fee.” There was no receipt, no explanation, and the money went straight into his pocket. The other cruiser checking in at the same time objected—rashly—and got the cold shoulder and blank stares. Had he persisted, we suspect that customs would have pulled his boat apart looking for contraband, and they probably would have found it.

Like most cruisers, we carry more alcohol than is permitted without paying duty. Thai authorities know it, since most boats come here from duty-free Langkawi, Malaysia. Arguing with customs over a few dollars is suicidal. Are we making things more difficult for future cruisers by paying extortion? Probably, but I challenge you to maintain your principles when you’re in a part of the world where bribery and extortion seem to be a way of life.

Shipping in a spare pump presents special problems. Customs seizes anything sent in, then waits for you to call. The duty you pay seems to vary with how desperate you are for the part. The rules are, to say the least, flexible, unpredictable, and irrational.

Spares

Which brings us, inevitably, to the question of spares. It used to be a standing joke that we carried spares for everything except the hull and mast. Now, it seems, we may be under-spared in vital areas.

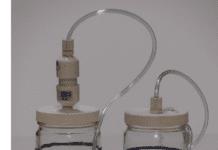

When we began overhauling the Shurflo freshwater pressure pump that had died in Bali, we discovered a bad bearing. We had every part to rebuild the pump, except the bearing. We were foiled again. Miraculously, a cruiser in Malaysia was placing an order with West Marine, and we were able to tag some parts onto his order. When we will actually catch up with him to get our new backup pump remains to be seen.

In a pinch, we could steal our saltwater washdown pump as a freshwater pump, so we’re not completely without options.

How can you possibly foresee what you will need? The answer is, of course, that you can’t.

We had both our alternators rebuilt in New Zealand after a technician there reported that our supposedly rebuilt spare was, in fact, non-functional. We installed one of those newly rebuilt alternators on our newly rebuilt engine. It bit the dust at about 400 hours, en route to Darwin, Australia. In Darwin, we had both our alternators torn down once more. I was so spooked, however, that I ordered a third alternator from Balmar in the US. We now have three identical alternators: one on the engine and two rebuilt spares. All I know for a fact is that the new one is working fine.

The engine raw water pump was another example. Three years ago, our original pump began leaking—a not-unusual happening. We took the pump to a reputable mechanic in Newport for a rebuild. At the same time, we decided to get a second pump. We installed the new pump, and put the rebuilt original away as a spare.

In New Zealand, before we bought the water pump that so nearly did us in, we installed our rebuilt original pump. It leaked. We then rebuilt the pump we had taken off the engine—it had been working just fine. It also now leaked. The mechanic tore down our two leaking pumps, created one non-leaking pump from the best parts of both, and gave us a box of leftover bits.

That’s when we decided to get the new pump. That pump, of course, has now turned out to be the wrong pump!

Now, we’re trying to do the impossible: have a new pump (the correct model) sent in from the US. Our pump simply isn’t available in Thailand.

“We can get it in 45 days,” said the Jabsco distributor in Bangkok. In 45 days, we plan on being in the clean, clear waters of the Indian Ocean, headed for the Maldives.

A call to Jabsco in Costa Mesa, CA got us the name of Depco Pump Company (727/446-1656), a Clearwater, Florida dealer. A call to Depco verified that they have the correct pump in stock. Depco is experienced at shipping pumps and parts anywhere in the world, and we’re hoping against hope that the pump can be on its way halfway around the globe to us, and that I can bail it out of customs without selling my soul.

I now have a new philosophy: Whenever we have a piece of equipment rebuilt, I am going to install it and test it. If it works, I’m going to leave it in place. My faith in the rebuilding process has been severely strained recently.

And how many spares should you carry for world cruising? As many as you can jam in every nook and cranny in your boat. That’s why cruising boats get so heavy. It’s also one reason that boats which depend on light displacement for speed—cruising multihulls, for example—rarely live up to performance expectations when loaded for serious cruising. If you’re going cruising in a multihull, you’d better keep it simple and light if you expect to get there any faster than your monohull friends.

In all seriousness, anything driven by a motor, and anything that spins at high speed for long periods of time, and which is critical to the operation of your boat, should be backed up with at least one, and preferably two, drop-in replacements.

Phone Home

Incidentally, I’m placing these overseas calls using a GSM cellular phone, roaming on the Thai cellular system. In Thailand, I’m using my US phone chip, with its US phone number. A good friend in Rhode Island called me a few days ago by just dialing the seven numbers of my Rhode Island cellular phone number. It cost him nothing to call me, but, of course, it costs me plenty.

We’re still a long, long way from the free lunch in global communications. Email is about as close as it gets, but it often takes a phone call to someone just to get an email address.

Preparation

These are busy times for us, but we’re not alone. There are now dozens, probably hundreds, of sailboats in Thailand and northern Malaysia getting ready to cross the Indian Ocean, headed for the Red Sea. There are perhaps 35 boats hauled out here at the Boat Lagoon in Phuket, most doing bottom painting in anticipation of a lot of hard sailing in hot waters in the months ahead, with few opportunities to clean the bottom.

Our Micron CSC bottom, applied in New Zealand, is holding up surprisingly well. It is slimy, but mostly free of hard growth. We have not touched it since launching the boat in March, but will certainly at least scrub it before leaving Thailand. We’ve put 6,000 miles under the keel since May 2000, and have another 5,000 miles to go in the next four months.

We’re trying to decide whether to haul here for a quick bottom paint job, or wait until we get to the eastern Mediterranean a few months from now. Thanks to high demand, prices for boat services in Thailand are not the bargain they were a few years ago, but are still much cheaper than in the US.

Often, unfortunately, you get what you pay for. At least half a dozen boats are sitting here with bottom gelcoat ground off, getting blistered bottoms “repaired.” Unfortunately, it rains here almost every day this time of year, and the boats are sitting outside, uncovered. There is no shrouding of hulls, dehumidifying, or checking for moisture content.

These sailors are wasting their time and money on cheap bottom repairs, still looking for the free lunch. Judging from the look of some of the bottoms, this is not the first time their bottoms have been repaired, and it probably won’t be the last.

At our last haulout in New Zealand, Calypso’s bottom still looked fine. The hull bottom was laid up with unpigmented isopthalic gelcoat and resin, and for good measure was overcoated by Jamestown Boatyard in Rhode Island with Interlux Interprotect 2000. The proper treatment of a new hull before launching, though expensive, seems to go a long, long way toward preventing long-term gelcoat problems.

The Politics of Cruising

The explosive political situation in the Middle East, coupled with documented attacks on yachts approaching the Red Sea, is giving the west-bound cruising community here ulcers. After the bomb attack on a US destroyer, Aden is not looking like a particularly good place to stop. Being an American-flagged boat is not easy at a time when the US is trying to act as mediator in a part of the world where no one seems to want a peaceful solution to very real problems.

This is a true story. Several megayachts here in Thailand, preparing to depart for the Mediterranean, have investigated hiring an ocean-going motor vessel crewed by armed mercenaries to escort them on the approach to the Red Sea. The cost is about $60,000. This may seem like a lot, but when it is divided between three large yachts with a combined value of $30 million, it seems like a small price to pay.

Our fear is that tensions may increase to the point where US-flagged sailboats in the Red Sea will become convenient targets for anyone who dislikes US foreign policy. Is this what cruising has come to?

We certainly hope not. Like most cruisers, we’re just looking for the next calm anchorage in clear water over a sand bottom next to a palm-fringed shore. Once the anchor’s down, we’ll get the awning up, put Diana Krall on the stereo, fire up the microwave to make a batch of popcorn, and pop the top on a cold beer. And maybe, just maybe, we’ll do another inventory of our spare parts in our spare time.

That’s what cruising should be about.