The U.S. Coast Guard estimates that more than half of the people who drown following a fall from a boat would have survived had they been wearing a personal flotation device (PFD). Unfortunately, standard life vests can be very uncomfortable and are thus not always worn by the average boater. In an effort to improve this situation, the USCG began certifying inflatable PFD devices as lightweight—though not inexpensive—alternatives to the bulky foam-flotation lifejacket. Here’s the bottom line: Because they’re smaller and more comfortable, sailors are more likely to wear these devices more often. Our last test (October 1, 2000) was conducted on the heels of the first USCG inflatable PFD certifications. Though we published a primer on PFDs in our October 1, 2001 issue, it’s time to review these lifesaving devices again.

Background

Inflatable PFDs come in two types: Manually activated and automatically activated. PFDs that have been approved by the USCG are classified as Type V, special purpose devices, and given performance classifications of either Type I, II, or III.

Currently, no recreational inflatable PFDs are certified for Type I performance. For reasons known only to the USCG, automatically deployed vests can display and advertise Type I or II performance while manual-only vests are limited to Type III. To achieve these performance ratings all the vests we tested must be worn while aboard ship.

Technically, according to Underwriters Laboratories Inc. (UL), which set the standards that PFD manufacturers must meet, the automatic inflatables are actually manually inflatable vests with automatic backup. That’s not how they’re being marketed in some cases, and not how the public perceives them.

According to USCG/UL standards, an automatic inflatable must provide a minimum of 33.7 pounds of buoyancy, or 150 Newtons (one Newton equals a mass of 1 kilogram times an acceleration of 1 meter per second). That sounds like a lot, since the average adult only needs 7 to 12 pounds of buoyancy to stay afloat in calm waters.

But waters often aren’t calm, and the extra buoyancy mandated for these devices keeps your head farther out of the water and away from waves; it also keeps you face up to prevent drowning even if you’re unconscious. PFDs of this type must activate within 5 seconds of immersion and inflate to the designed buoyancy level within 10 seconds.

In practice, as we found during our field tests, all this happens very rapidly, almost before the crew overboard (COB) is aware of what’s occurring.

Manually deployed inflatable devices with a Type III performance rating must provide 22.5 pounds of buoyancy (100 Newtons), but may offer more (we specify inflatable here because non-inflatable Type IIIs are only required to provide 15 pounds of flotation). Manuals are held to a stricter inflation standard than their auto-deploy brethren. They must reach designed buoyancy within 5 seconds of activation.

There are other standards as well, some of which we will discuss while reviewing the various models. All Type V inflatables must also carry an oral-inflation tube for backup. As a protection against premature or inadvertent inflation, Type V PFDs must withstand 120-degree temperatures at 80% humidity for seven days without self-inflating. (That’s a sliding scale; at 90 degrees, the humidity would rise to 100%.)

These, for practical purposes, are the standards.

What We Tested

We confined our test to nine vest-style inflatable PFDs in adult sizes, leaning toward units with both automatic deployment capability and manual mode. Seven of the nine tested had an automatic mode. Four makers provided us with test gear. (We do plan to test the belt pack inflatable PFDs in the near future.)

Mustang supplied a pair of vests: one manual, the MD3003, and one auto, the MD3031. Sospenders sent us three vests: two automatic units, the 38A LNG and the 38A HRN, and a single manual, the 38M HRN. Stearns sent its Ultra 4000, an auto-inflatable vest. Sospenders manufactures West Marine’s vests. The model we tested, the World Class (model no. 5328786), is an exact copy of the Sospenders 38A LNG. To round out the field, we added a pair of automatic units from the UK-based Crewsaver, the Crewfit 150N and 275N.

How They Work

The automatic PFDs, like the manual ones, consist of inflatable bladders within a nylon shell. Firing mechanisms differ in detail, but operate on the same principle: A spring-loaded pin is held in check by a water-dissoluble barrier. When the barrier is breeched, the spring is released allowing the pin to penetrate the CO2 cylinder and inflate the bladder.

Halkey-Roberts, the Florida firm that makes the inflators for both Sospenders and Mustang, uses a cellulose-based disk inside a bobbin to hold the actuation spring in check. Secumar-Stearns, a joint European-US venture, supplies the firing mechanism for the Stearns vest. It makes use of an aspirin-like, cellulose-based pill that is loaded in a lever-accessed compartment. Crewsaver uses their own firing mechanism in the two vests we tested. Another type of automatic inflator is available from both Crewsaver and Sospenders: It’s the Hammar inflator. It requires being submerged to a depth of 10 centimeters before it will activate, further limiting the chances of an inadvertent activation due to spray or rain. We did not test the Hammar system.

Inflatable PFDs aren’t for everyone. Users must be at least 16 years old and, depending on the model, weigh a minimum of 80 to 90 pounds, with a chest size ranging from 30″ to 52″.

Choosing a manual or automatic inflatable PFD is a tough call. If you get knocked unconscious or are injured, then you’d want the automatic PFD, which will turn you face up and keep you afloat. But if the boat capsizes and traps you under it, an automatic PFD will make it virtually impossible to swim down and resurface.

Making this decision depends upon a number of factors, including the type of boat you have, how you use it, as well as the predominate sailing conditions. For instance, if you sail offshore aboard a lively design—often in rough conditions—an automatic PFD might be the better choice because the risk of getting injured is greater. Manual-style vests may be better for slower boats where the risk of injury is not as great. As we said, it’s a tough call.

How We Tested

Two adults conducted all the hands-on PFD testing. Each donned every vest, jumped in a saltwater canal, and later rearmed/repacked the vests. Each vest was rated for ease of donning—how easily did the buckles and straps operate? Did they feel secure? Were they easy to tighten and loosen? Did they slip?

Once on, we rated each for comfort and fit (out of the water). To activate each automatic vest, testers jumped into the canal dressed in shorts, shirts, socks, and shoes from a height of about four feet above the water.

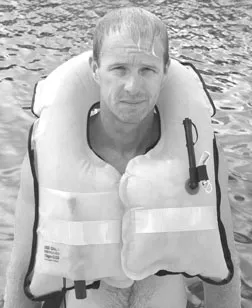

]All automatic vests began to inflatebefore the subject resurfaced. The manual vests were activated once the tester had returned to the surface after jumping in. Again, all the PFDs deployed as advertised. While in the water with the PFD inflated, the testers rated each vest for both comfort and fit. They then attempted to swim both on their stomachs and on their backs. They also simulated an unconscious person floating face down to determine if the PFD could turn them over and onto their back. All of the vests succeeded at this.

Our testers also used the oral inflator tube and whistle, and tried to adjust the straps and buckles while wearing the vests in the water.

Additional testing included a spray test to determine if automatic deployment could occur in rain or sea spray. We hit each automatic vest with a fresh water hose for a full two minutes with enough water flow to simulate heavy rain or sea spray. None of the vests inflated.

To confirm adequate lift was provided from this category of PFD, a tester tried one while wearing full winter clothing (even though air and sea temperatures were about 90 degrees). He wore two sweaters and a winter jacket, long pants and rubber boots. Even with all this extra weight, the buoyancy was far more than needed to remain on the surface—and easily flipped him over from a facedown position. This led us to forgo testing of all of the vests in the winter garb.

To select a winner, we used all ratings and each vest’s warranty period, buoyancy, and area of reflective tape.

Crewsaver

UK-based Crewsaver makes over a dozen different versions of inflatable PFDs. We tested a pair, the Crewfit 150N and the Crewfit 275N. Either can be equipped with or without a harness, D-ring, or crotch strap. Both are available with manual, standard automatic, and Hammar inflators. Manual requires the wearer to pull a handle for activation while both auto versions deploy the CO2 canister upon immersion. Both of our test vests were equipped with the standard automatic inflators. Our 150N was a standard vest, while the 275N had a harness and single D-ring. Crotch straps also accompanied the Crewsaver vests.

We didn’t like the buckle that comes standard on the harness version. We found it difficult to tighten and once taken apart it was tough to remember how to route the belt properly for reassembly. Our problems with the harness buckle were the reason for the 275N’s fair Donning rating. The plastic snap-lock buckle with the metal tension adjustment on the 150N worked far better, in our opinion.

The waist belt on the 150N can be adjusted easily while in the water with the vest inflated.

Testers agreed that the 150N was the most comfortable vest in the water. When inflated, it has more than enough room around the wearer’s chin and face. Crewsaver also provides a crotch strap to prevent the PFD from riding up, but we found it made little difference.

The 275N in the name stands for 275 newtons of buoyancy. That’s almost 62 pounds—and it shows. Once inflated, the 275N can only be described as huge, with each chest chamber measuring about a foot in diameter. For many sailors, this may be overkill.

That extra buoyancy allowed the 275N to turn over the testers faster than any other vest, and would likely allow the wearer to stay on top of the water better in rough seas. It has so much buoyancy that testers found it impossible to float horizontally in the water face down with this vest inflated. Fit and comfort around the face and chin while inflated were Good.

Re-arming/repacking a Crewfit vest is straightforward and simple. Deflate it using the inflator/deflator tube, unscrew the CO2 cylinder and replace with a new one, unscrew the automatic trigger and replace with a new one, then repack by folding and fastening hook-and-loop zippers. We rated the 150N Excellent and the 275N Good; the latter requires more folding to repack. Both can be rigged with manual-only activation if needed.

Neither of these vests is USCG certified though both are top-quality products certified to European standards. Both carry a three-year warranty.

Bottom Line: The Crewsaver Crewfit 150N standard automatic is our top pick. It garnered the only Excellent fit/comfort rating for in-water use, it repacks easily, has lots of reflective tape, and carries a three-year warranty. The 275N is quality gear as well, though, with more bulk and buoyancy than required by most of our readers.

Mustang

We tested the AirForce MD3003, a manually activated vest, and the AirForce MD 3031, an automatic vest. Both are updated versions of the vests we tested previously. Full harness and O-ring equipped versions of these vests are available in either the manual or automatic models. Both vests use Halkey-Roberts Inflators.

Both Mustang vests are similar in design and layout to the Crewsaver Crewfit 150N. The MD3031 carries a spare CO2 tank making it noticeably stiffer and less comfortable than the MD3003. Buckles and belt tensioning hardware on both Mustang units is virtually identical to the mechanisms on the Crewsaver 150N.

All in-water comments apply to both vests. Testers gave the Mustangs a Good for in-water fit and comfort, second behind the Crewsaver Crewfit 150N. They have slightly less space around the head, neck, and chin, but waistband tension can be adjusted while in the water with the vest inflated.

We rated both Mustang units Excellent for re-arming/repacking. You follow the same steps as described in the Crewsaver section. The only additions are the need to replace a water-soluble bobbin when re-arming an automatic system, and to check and replace as needed a plastic pin on either re-arm. All needed parts are contained in the re-arming kit. Mustang vests carry a 1-year warranty.

Bottom Line: If availability of the Crewsaver proves problematic or you must have a USCG-approved inflatable, we’d opt for either of the Mustang units.

Sospenders and West Marine

SOS Inc. carries a full line of inflatable PFD vests that offer a wide range of choices in size and capability. Both long and short vests are available, as are D-ring-equipped full harness vests, and all are available in manual and automatic models. Other options include crotch straps, tether lines, and safety lights. We tested two standard long vests with auto/manual activation: the 38A LNG and the West Marine 5328786 by Sospenders. We also tested a pair of harness-equipped vests, one auto, the 38M HRN, and one manual, the 38A HRN.

All four Sospenders vests were rated Good for on-land fit and comfort, and the two standard vests were also rated Good for donning. Both harness-equipped vests have large plastic snap-lock buckles and all-metal tensioning hardware on thehefty waistband. We liked this system and found it very easy to operate, rating the harness-equipped vests Excellent for donning.

We thought that the Sospenders vests were more uncomfortable to wear in the water than the Mustang or Crewsaver vests. They rubbed the chin and neck of both testers and put pressure on the throat when attempting to swim face down. All ride up on the wearer during inflation and must be adjusted for a better fit once inflated.

The harness-equipped vests are easy to readjust, and the standard vests more difficult. We rated all Fair for in-water fit/comfort. Even though the Sospenders units were the preferred in-water inflatable PFD in our last test, the improvements made by Mustang and the addition of the Crewsaver product to our current test have pushed the Sospenders units out of the top spot.

With the Halkey-Roberts inflator installed on all of our Sospenders vests, re-arming the CO2 cartridge is a simple and easy process identical to the Mustang units. It is the increased difficulty we found refolding and repacking the Sospenders vests that forced us to drop it to a Good rating. All Sospenders vests carry a one-year warranty.

Bottom Line: Though the Sospenders vests were our top pick four years ago, advances by others have pushed them back in the pack.

Stearns

Several types of inflatable PFD vests are available from this diversified marine products company. We tested the Ultra 4000 Model 1439, an auto/manual unit with a standard vest that uses a Secumar 4001 inflator contained in a clear plastic pouch. An extra CO2 cartridge is carried in a second pouch on the opposite chest tube. The 1443 model has a full harness and D-rings.

On land, we found the Stearns vest easy to don and adjust to fit. Once on, it has a comfortable fit. Like some others, it uses a plastic snap-lock waistband buckle that was easy to operate and felt secure when locked. The waistband is tightened with plastic tensioning hardware that worked adequately, though not as good as the best we tested.

The 1439 only managed a Fair rating for in-water comfort and fit. Both testers thought it had the least comfortable fit around the neck and face of all the PFDs tested.

Re-arming/repacking of the Stearns vest was rated Excellent. Like some of the other styles of inflator mechanisms we tested, the Secumar uses a water-soluble pill that, when dissolved, allows a spring to puncture the CO2 cartridge and inflate the vest. To re-arm this inflator, simply change the pill, located in a lever operated holding box, and swap the old cylinder for a new one with a quarter-turn. Repacking the vest material was easy and contributed to its high rating.

Stearns offers no predetermined warranty period on its marine product but states in writing: “Should a product with a manufacturing imperfection find its way to a dealer’s shelf, please write for written authorization to return the product for our evaluation. If found defective, we will repair, replace, or credit your account accordingly. We do not guarantee this or provide a written warranty, but extend our promise to fairly resolve all returns.”

Bottom Line: The Stearns’ Fair in-water fit and comfort rating in conjunction with its open-ended warranty, holds back this vest, in our opinion.

Conclusions

Given their high price, few owners will outfit their boats with a full complement of inflatable PFD vests. More often than not, the owner will buy one for himself and stock up on less-expensive PFDs to satisfy USCG regulations. So withthe boat already in full compliance, we see no reason not to recommend the Crewsaver 150N in spite of its lack of USCG approval. It scored high in all testing areas.

The Crewsaver 150N is more expensive than the others, but we think its excellent comfort and fit—especially in the water—and its easy repacking and rearming, make it worth the price.

For those sailors who prefer sticking with USCG-approved vests—or want a less expensive alternative—we’d recommend purchasing either one of the inflatable PFDs we tested from Mustang.

Also With This Article

“Value Guide: Inflatable PFD Vests”

Contacts

• Crewsaver, www.crewsaver.co.uk

• High Seas (Crewsaver’s U.S. distributor), 305/358-7455, www.highseasusa.com

• Mustang, 360/676-1782, www.mustangsurvival.com

• SOS Inc., 800/585-5876, www.sospenders.com

• Stearns, 320/252-1642, www.stearnsinc.com

• West Marine, 800/262-8464, www.westmarine.com