At least once each season, someone should make the trip up top to inspect the rigging. There can also be more immediate needs. An eagle could eat your wind instruments— as happened to me—or the masthead light burns out, and there is always the aggravating lost halyard. You can be winched up in a bosun’s chair, climb a halyard using ascenders, or climb a mast ladder (fixed or webbing). All of these require two sturdy lines that go clear to the masthead—one to support the ascent and the other as a safety line. Search PS archives for “Going Aloft” and you will find several articles on the topic (PS August 2019 “Years Later, Mast Mate Still Riding High,” PS October 2014, “Getting to the Top”), as well as a review of bosun’s chairs “Practical Sailor Tests Bosun’s Chairs and Harnesses,” PS June 2010.

However, once in a while these systems won’t work. For example:

• The halyards may be old and untrustworthy. A masthead sheave can be bad or suspect; we know a guy who decked out because he was climbing on a single line, the sheave axel failed, the rope dropped onto the sharp edge of the mast opening, and the rope cut.

• The only available safety line may be undersized; about 4,500 pounds breaking strength is required, which requires 3/8-inch polyester if only a few years old and 7/16-inch if 5-10 years old.

• The jib halyard may be suitable for hoisting, but if it is on a furler, taking it down is a minor pain. More and more often, the boat is fractionally rigged, and the jib and spinnaker halyards are all well below the masthead. The main topping lift may be undersized, replaced by a rigid vang, or simply nonexistent on sub-30 foot boats.

In extreme cases, the mast can be climbed like a rope using three prusik hitches. I’ve done this on a new-to-me boat when the halyards were just too gnarly to contemplate. The hitches are used in the same manner as the ascenders on a rope climbing system like the ATN Mastclimber. Other times, you can climb using the main halyard, but you need something for the safety line. Prusiks around the mast are perfect for this. In both cases you need an extra prusik for passing spreaders. The use of a prusik has saved the lives of many riggers, and is one of the first tricks a new rigger is taught before going aloft.

Climbing the entire mast this way is exhausting work. Repositioning the knots takes a few seconds each time. Passing the spreaders is awkward, since you have to reattach the prusiks above the spreaders, carefully moving one at a time. I’ve only done the whole length once, and though nothing went wrong, it was slow going. If there is a lot of work to do on the mast, taking it down might be smarter. If the halyards are that scary, you probably need new stays anyway.

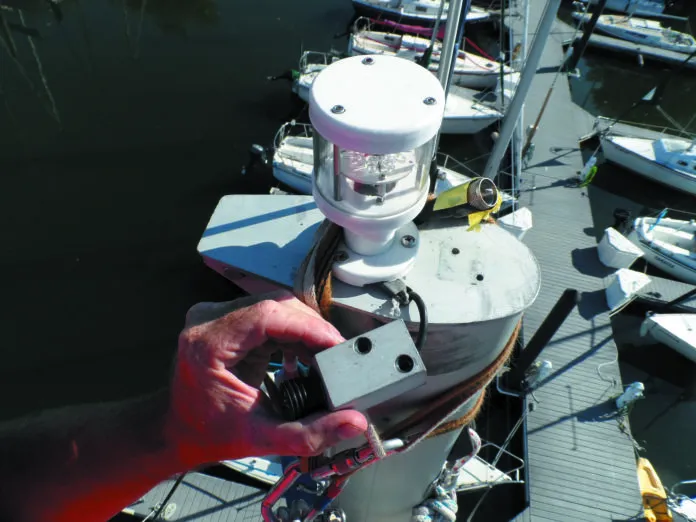

A more common application is to protect the climbing above the hounds on a 3/4 or 7/8 rig. Just climb the mast in the normal manner. When you reach the top of your safety line, wrap a prusik sling twice around the mast above the hounds, clip that to your harness and then unclip from the former safety line. Alternatively, you can just slack off the original safety line, leaving it in place as back-up and for the descent. Continue climbing, sliding the prusik up with each step. To descend, reverse the process.

THE SLING

We’ve used many materials over the years and none have failed to grip. Our favorite has become 3/8-inch polyester double braid, primarily because it is easier to handle with gloves on and we like to wear gloves while climbing, for increased grip and so that we can hold on to wire stays when needed. That said, webbing slings and larger diameter rope of sufficient strength works fine. Do not use hollow braid Dyneema, such as Amsteel. It is slippery on the mast and the knot can jam.

The sling should be long enough to encircle the mast twice plus about 8-12 inches for working room, depending on personal tastes. The prusik hitch itself is nothing more than a luggage tag hitch or larks head, but with the loop passed through twice. Animated knots has a video clearly showing how to make it (www.animatedknots.com/prusik-knot).

Always pull the knot or splice used to form the loop through first; this avoids this lump becoming mixed up in the hitch. Dress the hitch neatly; it will be easier to slide and grab with less downwards sliding. When moving the hitch up or down, loosen it only as much as needed; more than that and you will have to redress the knot, which is time consuming and awkward, since you are likely working with one hand.

Slings can be tied with high strength knots, such as a trace figure 8 or double fisherman’s knot. Webbing climbing slings are sewn. Finally, you can use an eye-and-eye sling (aka “rabbit runner” because the eyes resemble ears) a length of rope or webbing with a loop in each end. Two of the slings we tested were rabbit runners. These can work well and add versatility. The minimum loop strength should be 4,500 pounds; allowing for loss in strength in knots and over edges.

Retighten each time you move the knot, but using only a very light tug with one hand. If the knot is dressed neatly there is no reason put weight on it.

Aluminum climbing carabiners are lighter, cheaper, better tested, and will do less damage to the mast than their stainless cousins. Make sure these are UIAA approved. No carabiner should be used in a manner that allows the load or any object to bear on the gate. Locking carabiners increase security, but non-locking carabiners can be used as long as a single carabiner is never the sole or primary means of support.

SAFETY REMINDERS

Take a Class. Reading the instructions is not enough. There are many important details and there is nothing like a deep understanding of the larger principles and practice to avoiding important mistakes. A class on climbing the mast, taught by an experienced rigger is excellent, so long as it includes the method you will use. Climbing with the local rock-climbing club teaches rigging basics and movement.

I’m a 56-year old climbing addict, having climbed rock and ice all over the country continuously for four decades. It’s fun. I have also found there is no substitute for a breadth of experience and a deep understanding of how the gear works, and I’ve seen too many accidents that resulted from a brief training and a superficial understanding.

Do not take instruction from the guy who took a class once, went to Outward Bound, or was in the Boy Scouts. It needs to be from a meticulous person who has done this 100 times, who understands every detail, and can explain why each is important.

Harness Fit. There must be no possibility of falling out, even combined with the impact of an upside down fall. It is always possible to lean too far to one side, become inverted, and fall head first. A UIAA or OSHA approved as a harness is required, and few bosun’s chairs fully meet these requirements. Thus, the climber must either wear a full body harness or a tightly fitted UIAA approved seat harness that cannot, under any imaginable circumstances, be pushed or pulled down over your hips.

To emphasize, the waistband must be tight over your natural waist. If you do not have hips or a full body harness, you cannot climb. While a boson’s chair is more comfortable than most climbing harnesses, in most cases, you need to wear a harness as well for security.

Extra padding helps. I’ve duct-taped 6 x 10 rectangles of ½-inch foam exercise tiles to the leg loops of a rock climbing harness (see photo page 23). This prevents the circulation from being cut off from the thighs when hanging free, a real pain and a potential safety issue. They stay put just fine, but I take them off as soon as I am finished, storing them in them in the MastMate bag.

Two Attachment Points. This is an OSHA requirement. There are three common mast climbing methods: hoisted by halyard alone or with a tackle, climbing a halyard using ascenders (ATN Top Climber or similar), and climbing some manner of ladder (mast steps or Mast- Mate). While some riggers go up on a single line all the time, occasionally that line fails—that’s why they also use a prusik around the mast or be secured by another good halyard.

In two cases I am familiar with, the mast head pulley failed, the rope dropped on the sharp edge of the mast opening, and chopped. Yes, rock climbers use a single line all the time. How is this justified? The difference is that in industry and on boats, the wear history and condition of the equipment is often uncertain, whereas climbers inspect their ropes multiple times each day.

If you are going to be hoisted on a single line, you need to be 100 percent certain that the rope, pulley, and all hardware are in pristine condition. If not, have a crew member belay.

WHAT WE TESTED

Our main concern was that one of the test materials would slide, resulting a drop that would cause injury. We took an old Hobie Cat mast section (3” x 4.5”), made slings from common yacht and climbing materials, and pulled each until it slid. We then repeated the test at only 400 pounds, equivalent to a good bounce with body weight, to see if the slings would jam. We also tested on a 4” x 6” painted aluminum mast. Previously, Practical Sailor has tested the gripping power of other gripping hitches, on rope and stainless tubing (see “A Gripping Hitch That is a Cinch,” PS August 2009), and anchor chain (see “Hitches to Grip Anchor Chain,” PS May 2016). Useful for everything from making bridles for a sea anchor to securing awnings, a good gripping hitch is one of the most useful knots to have in your skillset.

OBSERVATIONS

The prusik does distort, and slip 6-8 inches as it takes a heavy load, but a little slippage on impact is a good thing, making for a safer stop.

None of the prusiks slipped at less than 1,500 pounds. When they did slide, it was a slow process, with tension remaining steady. You won’t just drop. Presumably, you are only 2-8 feet over the hounds; even a poorly dressed knot won’t slide past that.

None of the prusiks jammed under a 400-pound load. At most, light pressure with the fingers loosened the knot, allowing use to slide it up the mast.

climbing harness makes it more comfortable for

long periods of sitting.

A prusik can also be used for positioning at a mid-point of the mast, where it adds useful bracing, particularly if the boat is rolling due to waves or boat wakes.

Dyneema double-braid can be made into a loop using a double- or triple-fisherman’s knot. Many other knots can slip at high load. Set any loop knots hard on all prusik slings.

MOUNTAIN TOOLS WEBOLETTE

This rabbit runner is made from Dyneema webbing. It is light and compact, perfect for rock and ice climbing, but too small to easily manipulate with gloves on. However, it is very handy for securing yourself at the masthead, because it can be used as a loop, or wrapped around the masthead and threaded around instruments and stays as needed.

Bottom line: Light weight, strength, and versatility Recommend it.

SPECTRA/SPECTRA DOUBLEBRAID RABBIT RUNNER

Similar to New England Ropes’ Warpspeed, these 3/8 inch rabbit runners (also called eye-and-eye slings) originally were made of a material climbers call a cordolette. This consists of spectra cord with an eye tied in each end (Use a halyard knot or figure eight with the end seized to prevent slipping). Rabbit runners are handy because they can be used either as a loop or as a line that can be wrapped around several times to adjust length or used straight.

Bottom line: Recommended if you have some extra Dyneema double braid on hand.

3/8-INCH NYLON 3-STRAND

This inexpensive material was one of the top performers, but occasionally it was slightly more difficult to dress than double braid. A knot in threestrand is less secure than in double braid, and a splice would be too long.

Bottom line: This will work if it’s all you have.

3/8-INCH NYLON OR POLYESTER DOUBLE BRAID

These are inexpensive, a knot works, and splicing is easy once you’ve done a few. Holding was more consistent than three-strand.

Bottom line: Polyester is the Best Choice when wearing gloves. A size larger, 7/16” will work, but is bulky to carry aloft.

BLACK DIAMOND 19 MM NYLON RUNNERS, 120 CM

The old-standby of climbers for the last 35 years, a nylon sling offer a good combination of grip and economy. Shorter lengths have utility uses.

Bottom line: Recommended for mast climbing safety slings.

DYNEEMA SLINGS

Dyneema slings have virtually replaced nylon in climbing applications because they are lighter and more compact, but remember that a rock climber is likely carrying 8-16 runners of various length, and it adds up. Dyneema slings are also slightly more cut resistant, which helps. Unfortunately, they are also slender as a shoelace, slippery, and nearly impossible to handle while wearing gloves.

Bottom line: We like them for climbing, but this is not their best use.

CONCLUSION

I always clip a few spare rabbit runners and carabiners to my harness before climbing. I can tie myself off at the masthead. I may need a prusik sling for safety, climbing, or positioning.

The best material? The loop must hold 4,500 pounds for safety sake. We like polyester double braid, because it’s easy to handle with gloves. We also like the smaller Spectra double braid; it’s light and compact. Webbing is handy for slings used to secure us at the masthead; it’s light and will fit in tight spots rope will not. The only thing we recommend avoiding completely is Dyneema single braid

VALUE GUIDE: PRUSIK SLINGS

1. None of the recommended slings slipped, but some were easier to make and to work with aloft.

2. Polyester double-braid sling moved about 8 inches and the knot distorted at 600 pounds.

3. Webbing slides less than rope because it cannot roll, but ropes are easier to grip.

4. We tested each sling at 400 pounds, the maximum weight that would be applied while climbing the mast to see if any would jam. None did, although some were easier to move than others.