The obvious answer for how to maneuver when vessels meet at sea is for everyone to follow the Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, also known as the COLREGS. The COLREGs impose a system whereby all maneuvering will be predictable and completed with adequate clearance. But what if the rules break down? The boat is hove-to on autopilot and the crew is below. Visibility is poor and you got too close. A deck sweeping genoa blocked the view of a too-relaxed crew. Or perhaps the driver of the other boat either does not understand COLREGS, or in the panic of the moment, forgets. Sail long enough and it will happen to you. So how should you respond?

First, read the COLREGS again. Everyone can use a refresher, and the beginning of the sailing season is a great time. Think your way through each encounter. I like to post a cheat sheet for ship navigation lights at the helm, since there are a few I don’t see often enough to remember. See also “Collision Avoidance Confusion,” December 2023.

Today we’ll focus on what to do when the rules break down. In general, COLREGS Rule 17 applies only when the burdened (give-way) vessel’s actions alone will not be enough to avoid collision, or when the give-way vessel has failed to act at all. It then becomes the responsibility of the stand-on vessel to maneuver to avoid collision. Read that again. Even if you are the privileged vessel, you are obligated to avoid a collision even if the other party is at fault. And yes, even if you are the give-way vessel and failed to act in time, you are still obligated to act in the manner you should have. In other words: if you were supposed to turn to starboard, don’t turn to port now, because the stand-on vessel still has to assume that you will turn according to COLREGS (rules 9-16) at the last moment.

(a) (i) Where one of two vessels is to keep out of the way, the other shall keep her course and speed.

(ii) The latter vessel may, however, take action to avoid collision by her maneuver alone, as soon as it becomes apparent to her that the vessel required to keep out of the way is not taking appropriate action in compliance with these Rules.

(b) When, from any cause, the vessel required to keep her course and speed finds herself so close that collision cannot be avoided by the action of the give-way vessel alone, she shall take such action as will best aid to avoid collision. [Note: this includes inaction by the give-way vessel.]

(c) A power-driven vessel which takes action in a crossing situation in accordance with paragraph (a)(ii) of this Rule to avoid collision with another power-driven vessel shall, if the circumstances of the case admit, not alter course to port for a vessel on her own port side.

(d) This Rule does not relieve the give-way vessel of her obligation to keep out of the way. Rule 19, Conduct of vessels in restricted visibility, is also relevant, since poor visibility can result in a situation where Rule 17 applies. Note that there is no reference to stand-on vs. give-way. This is because in restricted visibility it is often not possible to be certain of the status of the other vessel: power, sail, restricted ability to maneuver, etc. Additionally, the duties and directions of turns are the same. This is useful symmetry.

Rule 19. Conduct of Vessels in Restricted Visibility.

(a) This Rule applies to vessels not in sight of one another when navigating in or near an area of restricted visibility.

(b) Every vessel shall proceed at a safe speed adapted to the prevailing circumstances and conditions of restricted visibility. A power-driven vessel shall have her engines ready for immediate maneuver.

(c) Every vessel shall have due regard to the prevailing circumstances and conditions of restricted visibility when complying with Rules 4 through 10 (§§ 83.04 through 83.10).

(d) A vessel which detects by radar alone the presence of another vessel shall determine if a close-quarters situation is developing and/or risk of collision exists. If so, she shall take avoiding action in ample time, provided that when such action consists of an alteration of course, so far as possible the following shall be avoided:

(i) An alteration of course to port for a vessel forward of the beam, other than for a vessel being overtaken;

(ii) An alteration of course toward a vessel abeam or abaft the beam.

(e) Except where it has been determined that a risk of collision does not exist, every vessel which hears apparently forward of her beam the fog signal of another vessel, or which cannot avoid a close-quarters situation with another vessel forward of her beam, shall reduce her speed to the minimum at which she can be kept on course. She shall if necessary take all her way off and, in any event, navigate with extreme caution until danger of collision is over.

Note that in poor visibility (rule 19) there is no such thing as a stand-on vessel. The meeting can become in extremis very quickly, and the status of the other vessel (power, sail, restricted in her ability to maneuver) may not be apparent. The status provided by AIS, if available, may not be correct. In head-on meetings between power vessels, both vessels are burdened; because of yawing and slight differences in observation point, anything within one point of dead ahead is considered head-on. In these circumstances, always turn to starboard.

VISUALIZING THE SET UP

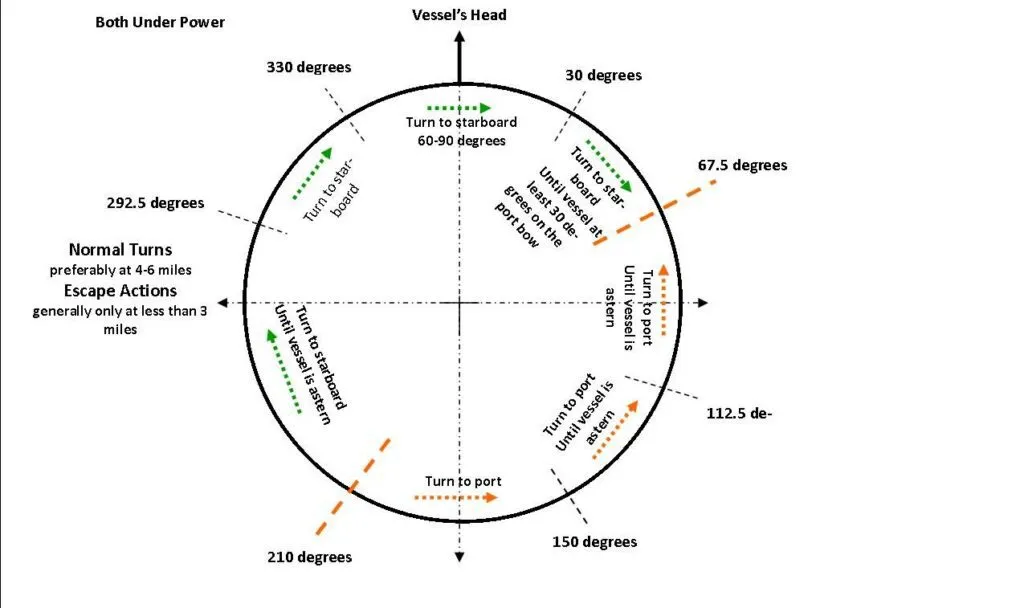

Now that we’ve established that every vessel should avoid a collision, even if you’re privileged, the matter comes down to which way to turn to get out of harm’s way. In 1947, Commander Davis N. Lott, USNR, contemplated various scenarios pertaining to collision avoidance while stationed at Pearl Harbor. Commander Lott came up with a series of polar diagrams that suggested evasive actions for vessels meeting. Even close to eighty years later, in the golden age of GPS, Commander Lott’s plots are still instructive.

There are four general principles:

- Follow COLREGS. Just because the actions are taken in extremis does not remove the benefits and the responsibility to act predictably. This results in most turns being to starboard. It is also almost never correct to turn to port if the other vessel is to port.

- Turn away from danger.

- Avoid turning broadside.

- Reduce closing speed by turning away.

We will present some of these scenarios in turn:

COLLISION AVOIDANCE IN EXTREMIS

In collision law, these maneuvers are to be taken only in extremis, when you are in a situation that, in your judgment, the only way to avoid collision or minimize damage is to maneuver on your own, even though COLREGS calls for you to hold course and speed. The rules are supposed to prevent vessels getting this close, so whenever this happens both vessels will be apportioned some share of responsibility.

This whole subject can be avoided if course changes are made early and are obvious. For large ships, this is typically within 4-6 miles. A 950-foot long Panamax freighter will take ¾-mile to turn and 1.5-2.5 miles to stop. If you are within ½-mile of the bow they may not even be able to see you, depending on the stacking of containers. The more nimble maneuvering characteristics of recreational yachts allows us to delay maneuvers to within 400-600 yards of other recreational yachts. Yes, we can maneuver in just seconds, but good decision-making can take minutes, so don’t cut it razor-thin when you are in proximity with any commercial vessel.

HOW TO GAUGE DISTANCE

Assuming 20/20 vision, at 300-400 yards you can make out people on the deck of a working vessel, but just barely and with no certainty. If you can see people clearly, you are too close. Alternatively, a 35- to 40-foot boat will appear the size of the width of your hand when your arm is extended. Obviously, this depends on the angle of the boat, and the minimum distance depends on whether you are heading directly towards each other, so it is only a rule of thumb. If the ship is coming head-on, you are really far too close If a ship is 1000-yards away, closing speed is only 2 minutes at full speed. Another rule of thumb: From the helm, if you can see the wake of a ship, it is within 3 miles, or less if there are waves. Binoculars may be needed; this is based on the curve of the earth, not the height of the wake. SOME EXAMPLES

This has happened to me, both upwind and downwind. Imagine a popular sailing area (Annapolis, MD in summer) where all of the talk about avoiding commercial traffic miles before crossing is just silly; you can’t make serious adjustments until within 200-300 yards because of the constantly changing situation. Because of this, COLREGS really matters, as does standing-on when you are supposed to. If everyone gave-way even when they didn’t need to give-way, the result would be a sidewalk shuffle and more collisions. I’m sure most harbors are like this for ships.

I was sailing to weather on starboard tack at 10 knots in a fast, light 27-foot catamaran. I had been observing a port tack boat that was now just 300-400 yards away (about 100-140 seconds if you are both sailing fast). The boat had well-trimmed laminate sails, suggesting a racing boat with an attentive crew. I could have tacked away, but there was another starboard tack boat to windward, parallel about 40 yards away and on my quarter. I had passed him a few minutes before, but if I tacked and crossed, I would be the give-way boat about the time I was up to speed. At this moment, standing-on felt safer. After all, the port tack boat must see two starboard tack boats crossing. The port-tack boat turned slightly to starboard and the bearing was drawing aft. It appeared he would duck under my transom by 100 feet or so, a normal crossing distance in these “racy” waters. I assumed he would pass behind the other starboard tack boat too, if he continued his turn.

When the boat was quite close (20 seconds) I realized that the wind had shifted back and that we were again on a collision course. In fact, the port tack boat had not changed course for me at all. He was only temporarily headed. A few seconds later, I realized that they had a deck sweeping genoa, no bow watch, and they didn’t know (or never knew) the either of us were there. At this point the closing speed was about 20 knots, or a boat length per second.

I tacked away FAST, passing within 15 feet by the time I was through the tack. I turned sharply enough to pass behind the starboard-tack boat to windward. I yelled something appropriate to the circumstances. The helmsman started leaning low, looking all around, suddenly realizing his mistake. He continued straight, just missing the other starboard-tack boat.

My take-away: ALWAYS make sure you can see the helmsman’s eyes on the opposing boat and you have his attention when it will be close (not that close!). I also keep an air horn at the helm. It has been useful a few times.

The safe maneuver in this instance was to tack away, because it reduced the closing speed and angle. If there was to be a collision, a glancing blow from aft is safer than getting T-boned. If I had turned to port (easier for me), the closing speed would have increased to over 20 knots, and if he had turned to starboard to take my transom at the last moment (not unlikely with racers) I would have been dead and nearly 100% at fault. The collision would have been head-on with a 30-mph closing speed, as both boats accelerated onto a fast reach.

Sailing fast in a crowded harbor was a risk factor. The only thing that saved the day was being ready to tack away in an instant. Never coil away your sheets unless far from traffic and obstructions.

ANOTHER EXAMPLE

In this case the reaction was different from the Rule 17 recommendation because the other boat was sailing and the stand-on boat had established communication.

On the way out to the course, an America’s Cup boat was slowly gaining on a Rhodes 26, primarily because she could point higher. Both were on starboard tack, the AC boat very close behind and slightly to leeward, when she decided to tack below us. The AC bowman hailed the Rhodes 26 to “hold course,” but as her bow came across the stern the Rhodes 26 helmsman could see they were going to hit. The AC boat was apparently closing faster than they thought and waited too late to tack. The Rhodes 26 bore off and just barely pulled away, missing by a thin six inches.

In this case, the approach angle was right between the dividing line (210 degrees) on the Lott diagram, so either a turn to port or starboard could be valid. However, a starboard turn would have meant tacking in front of the AC boat, and the helmsman also knew, from communication, that the AC boat was tacking (turning to starboard). Thus, bearing away slightly to increase speed was the right call.

TRUTH IS STRANGER…

Another example: In this case, the need to be at the wheel at night and in limited visibility is clear; emergency maneuvers are not possible if no one is at the helm.

A 40-foot yacht is sailing at night on a starboard tack with a reefed main sail. The boat is on autopilot and the helmsman is in the cockpit but not behind the wheel.Suddenly an unlit 76-foot fishing vessel appeared dead ahead-on a collision course. There was less than 10 seconds before colliding.

The boats collided. The sailboat limped back to port, where the insurance company declared it a total loss. The fishing boat crew denied they were unlit, and further, that they were engaged in fishing and thus claimed they were the stand-on vessel (trawling with nets—the outriggers were deployed but not the nets) because they were restricted in their ability to maneuver. As a result, the insurance settlement was less than complete. The yacht owner said that nets were not set.

LARGE SHIPS

A common case involves a ship holding course, and then suddenly changes course to enter a side channel or something else the recreational sailor did not expect. While your actions are not “in extremis” for you, they may be for the freighter, because of his much longer response time and potential draft restriction. Thus, your response should probably follow Rule 17. It’s too late, from the ship’s perspective, to make alterations under Rule 12-16 etc. Even if you are the stand-on vessel, you must maneuver to avoid a collision.

I was sailing singlehanded across the Chesapeake at about 10 knots with a chute. I had been observing a tug pushing several barges ever since he came over the horizon, but it seemed clear he would pass about a mile in front of me.

When about a mile away, the barge suddenly turned to enter a tributary, creating a collision course. I was monitoring the VHF. I was immediately hailed and told that I would be run over if I did not change course.

I didn’t argue the matter and jibed away. It was not in extremis for me, but it may have been for him, even though the situation was of his creation. He could have hailed me before making the turn, since my course and speed had been steady for 10 miles and I had been monitoring the VHF.

Ships change course for many reasons. There could be standing orders that require the master to maintain or stay above a designated keel clearance, which is not the same as following a channel. The closest point of approach between other ships is another hard and fast standing order, as is maintaining an accurate course on ranges. For the ship, even a large bay contains waters that are shallow for them, and it takes miles to turn or stop.

ERRATA

Respect vessels that are RAM. In ”RAM Lights For Sailboats,” June 2022, we included being hove-to as a status that could be considered restricted in ability to maneuver (RAM). This was incorrect. Even though maneuvering could be difficult and hazardous in survival conditions, a boat that is hove to is underway. We stand by our feeling that boats that are dragging a drogue in survival conditions (not for comfort) can be restricted in their ability to maneuver; they can only turn ~ about 10-20 degrees, the drogue cannot be recovered under high load, and cutting the drogue loose may significantly reduce the chance of surviving the storm. True survival conditions. A boat hanging to a sea anchor might well be consider not under command in the most extreme conditions, with the cabin sealed and the crew huddling in fear that the cabin may flood if the companionway is opened. But these situations can only be claimed if the captain believes he is in conditions so extreme that he cannot maneuver effectively, no matter how urgent the need. He must also display lights or day shapes confirming his status, so that other vessels understand that no matter the need, this vessel is not going to maneuver. Lacking lights and day shapes, watching the AIS and hailing on the VHF will help.

How to handle large ships. Normal turns can be performed at a distance of six miles or more. Outside this distance, we are clear to maneuver as we like to avoid collisions. But once within the normal turning distance of the larger, less maneuverable vessel, we are bound by Section 2. Once we are within the “in extremis or emergency distance for the less maneuverable vessel,” possibly as much as 2 miles for a large ship, we are bound by Rule 17. Suddenly, being a sailboat does not automatically make our vessel the stand-on boat. It’s a simple situation to avoid—if ships follow steady course. But often, they must turn to follow a channel, enter a side channel, or even line up with range markers to maintain bottom clearance. They might be avoiding another large ship you even considering. Monitoring 16 helps; they may have contacted you and you missed it. Whether sail or power, you must avoid as per Lott’s polar diagram, because that is what the ship’s crew expects. Some will call this the rule of tonnage; it does not exist. What does exist is a very real difference in the distance when rule 17 applies.

If you are disabled in the channel and there are ships on the horizon coming your way, get on the radio and tell them. Display distress signals.

Recreational vessels,both under power. Rule 17 applies and we suggest you consider the polar diagram from Commander Lott (above). The smaller size of our vessels suggests some heading changes. In some cases, stopping might help, particularly in narrow channels, remembering that reverse thrust dramatically reduces the turning effect on boats that depend on prop wash over the rudder for rudder authority. Better control is maintained under power and the other vessel may not expect you to be slowing.

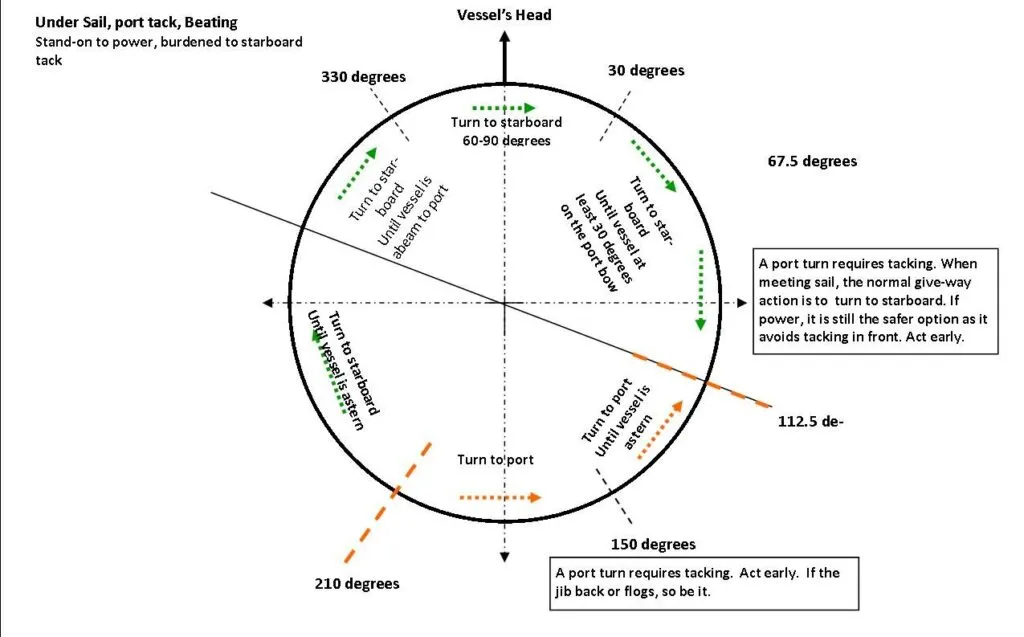

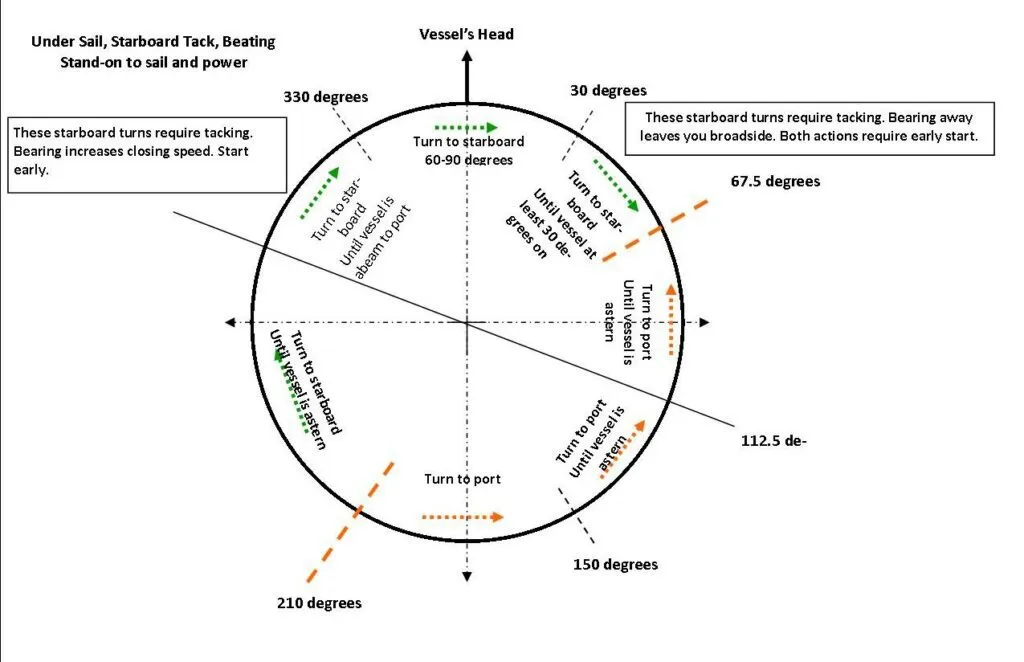

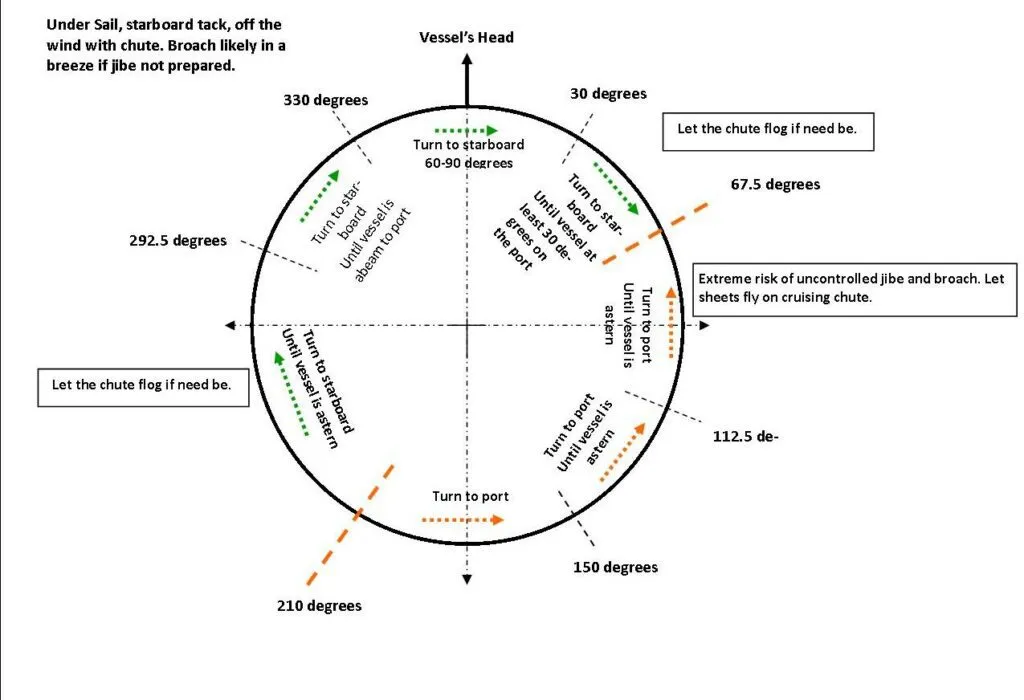

Under Sail. Always be ready to tack or jibe. After each maneuver, prepare the lines for the next. Though you may have no crew on deck and not be prepared to tack or jibe, at least you can make the turn and let sheets fly if needed. Coiling or storing neatly away in bags is for harbor and long passages offshore. They should be flaked and ready.

The recommended turns are mostly the same, though in some cases the risk of an unplanned tack or jibe leaving the boat unmanuverable may change our decision points by a few degrees. But don’t be afraid to let the sheets fly and make turns you aren’t ready for; the boat will likely carry enough way to get you out of a tight spot and the damage and injury will be less than getting T-boned.

Under Sail, Other Boat Under Power, Including Motor Sailing. Ideally, we would follow Lott’s polar, but tacking and jibing without preparation or in rough conditions can leave you dead in the water or at least unmanuverable. A blown tack can leave you in irons. A spinnaker plastered against the rigging can result in a broach. A jibe can also take a lot more distance to do anything safely. And yet, heading up and flogging the chute will leave you dead in the water and susceptible to a potential broadside collision. Thus, we offer warnings over modified polars diagrams, since tearing a sail is better than colliding.

Both Under Sail. A likely possibility is that the other skipper is accustomed to close crossings, particularly in areas where racing is popular. The port tack boat is likely to wait very late to take a starboard tack stern. Can you see their eyes? If so, likely all is well. Don’t turn to port; that will result in a head-on collision. If you cannot see their eyes because of a deck sweeping sail, blow the horn early. A head should appear, followed by a turn.

SUMMARY

Sound the horn if you are stand-on and the other vessel has not maneuvered as you approach your comfort zone. This alerts the other boat, and if you sailing the the privileged vessels, alert the other vessel that she may not be doing what she should be doing. Of course, this by itself does not make it clear which boat is privileged, and blowing a horn doesn’t make you privileged, but if you are the one getting honked at, it may be a hint that they believe they are privileged and will maneuver in that way.

Always be ready to maneuver, including tacking or jibing, whether you believe you are the privileged vessel or not. Don’t be afraid to let a sail flog. That’s better than pinning it against the rig, stopping the boat, and losing maneuverability. Avoid getting caught in irons or in a broach. But most importantly, don’t become frozen into inaction; that is the most common cause of collision when you are in extremis; fear of doing something wrong. In its simplest form, the in extremis rule is “turn right, unless the other vessel is over your right shoulder. Sometimes the required turn is counterintuitive in the moment, and special cases may require departure from the norm, particularly when it is more of a close call than a certain collision, or if you know the other boat will maneuver in a certain way. However, the underlying principle is that the other vessel may also turn at the last moment, and if he follows the rules, you want to be doing what is expected of you, which in nearly all cases is to turn to starboard unless the other vessel is over your right shoulder.

It might seem logical that having to tack or jibe might alter your decision tree, but when we walk through the cases, we find it really doesn’t. Avoiding a collision requires action, not excuses.

Images

- From Collision Prevention, 1970, Commander Davis N. Lott, U. S. Naval Reserve. This was developed while he was leading a collision avoidance school at Pearl Harbor after WWII. It was written before COLREGS, and yet remains the standard for ships.

- Four slightly different collision avoidance polars for sailors. The changes are slight, more in the manner of warnings.