I often wonder what the Norwegian yacht designer Colin Archer would say about today’s performance cruising boats, with their open transoms rolling out the welcome mat to any following sea. Archer was a Norwegian naval designer best known among naval historians as the designer of Fram, the ship arctic explorer Roald Amundsen used to reach the South Pole.

Among American cruising sailors though, Archer is more commonly linked to the iconic double-ender, the Westsail 32. The Westsail is a modern iteration of Archer’s famous RS-1, a 46-foot redningskoite, or rescue boat, launched in 1892, And like the redningskoite, the Westsail’s cockpit is noteworthy for its scant volume.

The modern cruiser, even a small one, have room for two couples to comfortably enjoy a sunset cocktail. The Westsail has little more than a footwell. The reason for the tiny cockpit is obvious to anyone who has sailed a Westsail in steep following sea: it is not uncommon for a breaking wave to wash aboard, spill into the cockpit, and douse the unfortunate person at the helm. Fortunately, the cockpit drains quickly through a pair of ample drains.

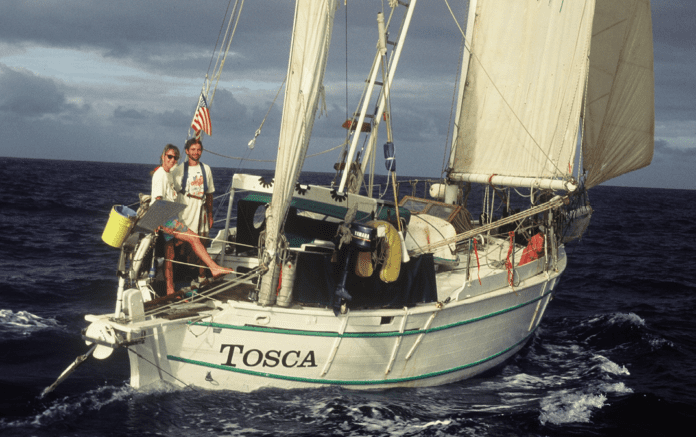

This happened frequent enough aboard my own double-ender Tosca, a William Atkin Thistle (another redningskoite heir) that we had a name for it—bath time. During those unfortunate passages when contrary wind and current conspired to set up a steep breaking sea, “Put your boots on honey, it’s bath time,” was the cheerful refrain during changes in watch.

This month we take a look at the pros and cons of open transom designs. The report is a reminder that design decisions are not necessarily good or bad, but that they have consequences, some more serious than others. Any choice that brings the captain or crew closer to the water raises the likelihood that they will get wet. Any opening in the hull increases the chance that water will surge below.

Fortunately, Tosca’s miniscule footwell, and nearly impenetrable deck layout—three small ports, one sliding companionway hatch, a compact lazarette, and one main saloon hatch—made it nearly impossible for breaking waves to go much further. Nevertheless, before setting out across the Pacific we took extra measures to seal the boat, so that even in a knockdown, so long as all the ports and hatches were closed, the cabin would stay dry. In contrast, a brief survey of the boats bound from Florida to the Bahamas last winter revealed

design decisions that seemed better suited for pool patios.

• Mammoth cockpit lockers with poor latches and toy hinges.

• Sugar-scoop swim platforms with poorly-latched, “wet” lockers that are not fully sealed from the main cabin.

• Tiny cockpit drains on spacious cockpits.

• Flimsy, or poor-fitting companionway drop boards.

• Three-inch high companionway sills—or no sill at all.

These vulnerabilities are not uncommon. In fact, relatively few cockpits on production cruisers can be properly buttoned down to take a boarding sea. In the months ahead we’ll be looking lockers, hatches, and ports and how best to seal them. Every boat is different, so if you have a hinge, gasket, latch or modification that works for you, we’d be interested in hearing about it.