Did you know the accuracy of your electronic compass significantly affects features of your Furuno, B&G, Raymarine, Garmin, and similar multifunction display (MFD) to offer situational awareness of wind and water?

If you are willing to clean and calibrate your boat’s speed through water (STW) paddlewheel and compass very accurately, many MFDs manufactured within the last ten years offer features to graphically show with arrows the effect of the wind and water on your boat. Some provide additional features, such as drawing on the display a line for the upwind course your boat could achieve in current conditions if you were to tack or jibe at the present moment. Some MFDs, like the B&G Zeus 3, can even guide you to the start line of a race better and predict at what angle the wind will be off your bow on each leg of a racecourse, helpful in deciding in advance how you will set your sails.

If your boat’s sensors are not spot on, the graphical arrows of wind and water offered by the MFD will point in the wrong direction or be otherwise useless.

That is where Furuno’s SCX20 comes in. It provides a no-nonsense superaccurate electronic compass sensor to power your MFD into delivering the features above.

With the SCX20, your existing MFD, and discipline in keeping your paddlewheel clean and calibrated, you can more quickly understand the forces of wind and water on your boat and reduce the learning curve of being a better sailor.

4 GPS SENSORS

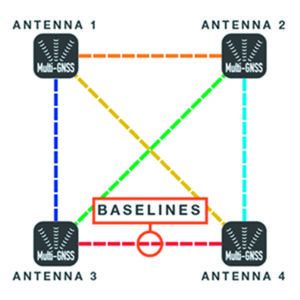

Instead of measuring the earth’s magnetic field, for about $1,200, Furuno offers a remarkable electronic compass that determines your boat’s compass heading using the best two of its internal square array of four GPS sensors that fit in an antenna measuring less than 10 x 9 x 5 inches (L x W x H).

Not to be confused with a GPSprovided course over ground (COG) ‘compass like’ reading (your boat’s actual progress over ground irrespective of where the bow is pointing), the SCX20 provides your compass heading and the direction your bow points.

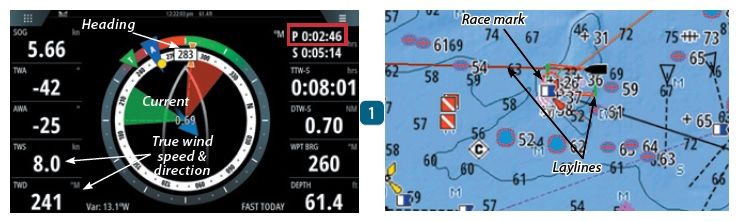

The display illustrates:

– Direct sensor output of compass heading, course over ground (COG), and apparent wind angle (AWA);

– Calculated values for true wind angle (TWA);

– Calculated tidal current direction and speed (.33 knots).

The SCX20 improves the accuracy of all calculated values. The yellow dot (bearing to waypoint) is the current course based on GPS COG. The red and green shaded areas, which change size based on recent wind shifts, are calculated positions for the port and starboard laylines. A databox shows an estimated time left on current starboard tack before reaching the port tack layline (29:33 minutes in red square).

Most MFDs can offer you better situational awareness graphically with the effect of wind and water provided as an arrow showing the strength and direction of forces against your boat by wind and water. This feature, for example, has been available going back before 2006 on products like the original Raymarine E-80. It was hampered by inaccuracies in both STW and fluxgate compass information, causing it to often show nonsense, like the direction of tidal current coming from nearby land.

More modern MFDs additionally overlay red and green lines showing the sailor calculated lay lines after which sailing moves them away from their destination and the direction their boat would be able to achieve upwind if they were to tack at that location on the map. An MFD can even help the sailor line up and approach a race start at the ideal time.

With bad sensors or calibration, these features are useless.

Except for apparent wind angle, apparent wind speed, and speed through water, every other MFD value provided is a mathematically calculated estimate rather than a measurement. The estimate can be rather bad, as small inaccuracies in heading and speed through water can translate into outsized estimation errors in the force of wind and water.

of headers and lifts (indicated by red square). A series of negative numbers when sailing upwind would indicate that the wind is shifting in a direction that might make the opposite tack more efficient. An accurate compass makes it far easier to calibrate this function to work correctly in small wind shifts.

This is because the forces being estimated are based on the difference between the two-dimensional vector your GPS provides the MFD (course and speed over ground) and two-dimensional vector your paddlewheel and compass provide the MFD. That difference represents the forces from wind and water acting on your boat. If you don’t start off having the paddlewheel and compass precisely calibrated, the MFD will calculate a force that isn’t there, and then draw lines and arrows for those forces and display lay lines incorrectly.

For example, if your STW is off by ½ knot, it could go harmlessly unnoticed on an instrument display showing boat speed in one dimension, but allow the MFD to calculate the direction of the water under your boat in two dimensions, and it could very well appear that water is improbably coming from a landmass and your lay lines could be off by as much, or more, than 45 degrees.

HOW WE TESTED

We took the SCX20 for a test drive on Strider, a J/109 sailboat configured for racing and cruising. The existing Precision 9 B&G compass is tucked below the V-berth 2 feet ahead of the mast, in a near-optimal location away from magnets and power wires. Unlike the Precision 9 and most compasses that need to be 3 meters/9 feet from any magnetic source, including DC power wires that carry unshielded DC electric current, the SCX20 has no problem on a cabinet in the forward stateroom just below the ceiling and 5 inches from a stereo speaker.

Unlike most satellite compasses, this compass works just fine with a fiberglass deck above, a carbon fiber spinnaker sprit next to it, and an aluminum mast three feet away. Quantum racing sails sweep back and forth overhead, as do people and an occasional ocean wave.

While this position would not work in an aluminum or carbon fiber hulled boat, in most fiberglass boats you are simply looking for an easy place to install it near the center of the boat. The SCX20 was designed to overcome reflected signals from components nearby, a problem with older generation satellite compasses that cannot handle satellite signals being reflected and arriving at the sensor multiple times.

Strider has two other compasses, including a Maretron solid-state compass dedicated to the autopilot and an inexpensive solid-state compass— similar to the compass in your smartphone— built into her main GPS, a B&G ZG100.

ACCURACY

Eric Steinberg, President of Farollon Electronics, and past electronics expert for America’s Cup yachts, shared that currently he sells the Thrane LT- 500 compass to clients demanding the best in compass performance. With 11 sensors the LT-500 can obtain 1.5 degrees of dynamic accuracy. However, if crew brings aboard any magnetic objects, that is not achievable.

Comparatively the less expensive Furuno SCX20 is 3 times better at 0.5 degrees. According to Furuno: “because the SCX20 uses four multisystem GNSS transceivers, it is more accurate than any known sensor from any competitor that they have tested. That same accuracy can be obtained from Galileo and Glonast as well as U.S. GPS satellites”.

RACING

Racing sailors benefit from a highly accurate compass because they can use it to better calibrate their wind instrument at various wind speeds, which in turn allows their racing computers to offer up a better measurement of lifts and headers as the wind changes direction. When racing upwind, knowing you entered a header is a key consideration in choosing when to tack in the pursuit of a faster time to your next mark (see adjacent images).

A more accurate compass, like the Thrane and now the SCX20, also makes it less frustrating to perform the exercise of tacking back and forth in the wind while capturing correction values for the computer that applies corrections to your wind instrument. Obtaining this ‘true wind’ correction is less of a chore with a great compass.

HOW THE SCX20 WORKS

The SCX20 compares slight timing differences of the GPS signal arriving at each GPS sensor. By measuring these differences, the SCX20 can determine how far off-center any two GPS sensors are from being perpendicular to any given satellite. The SCX20 then determines the boat’s compass bearing, providing a reading like a magnetic compass rather than a reading like a GPS course over the ground.

This compass heading is continuously recalculated and sent over the NMEA-2000 network as if it was a magnetic compass. The compass requires very little power drawn from your NMEA-2000 network, about half the equivalent of a 45 lumen LED navigation light bulb, something well within most boats’ power budget.

SCX20 INSTALLATION

Unlike the placement of a typical magnetic compass for which a location needs to be 3 meters from unshielded DC power wires and anything magnetic (including personal items your crew might carry aboard), the placement of the SCX20 is limited only by personal aesthetics and by materials that block GPS signal across a wide area above it. There is a slight advantage to getting close to the center of the boat.

In choosing an installation location, there are multiple mounting accessories available from Furuno that allow the SCX20 to be mounted flush with the deck, or on a rail mount. If your boat isn’t constructed of carbon fiber, metal, or other materials that entirely block GPS signals, you can consider installing inside your boat.

The SCX20 is pretty immune to signal blockage from objects and people. The quad antenna design of the SCX utilizes an “all-in-view,” six-baseline multipath correction algorithm. If signal blockage occurs in one direction, it is instantly corrected by using another baseline. This unique and revolutionary design, as opposed to a single baseline calculation on all other satellite systems on the market (including other Furuno products), allows it to be mounted almost anywhere. The Furuno design team even developed the top surface of the antenna with sufficient thickness and support so that a person could stand upon it without damage.

In addition to the cost of the SCX20, you need a Furuno instrument to configure the compass, providing input such as the physical distance of the sensor from the center line of the boat, height above water, etc. During operation any vendors instrument or MFD will do. On our test boat, we used a Zeus 3 (see PS December 2017, testing the B&G Zeus 3).

Without the need for magnetic fields, there is no comparable setup step to driving the boat in circles. Never do that again.

Senior Product Manager Eric Kunz of Furuno said developers found that the SCX20’s four multi-system GNSS (global navigation satellite system) transceivers make it nearly immune to placement problems that can hinder other satellite compasses.

OBSERVING ACCURACY

Before describing the test results on Strider, let’s describe the expected effects of having a more accurate compass.

The accuracy of the SCX20 shines when the user wants better two-dimensional situational awareness in the areas of set (magnitude of current) & drift (bearing of current’s flow) and wind direction. Also, as with all precision sensors that quickly report changes in heading, the radar images of other boats and the shoreline are free of the typical noise induced when a compass cannot keep up with the boat’s motion.

SET & DRIFT

Our boat’s MFD can measure (A) the motion of the water between the boat and the water with a paddlewheel and compass, and (B) the motion between the boat and the ground with the GPS. The modern MFD can then subtract (A) from (B) to calculate the motion between the water and the ground and display a directional arrow pointed towards the boat showing the calculated force from the water.

For a powerboat, this would be the force of the current. In a sailboat, things are a little more complicated, as the water offers an additional counter force against keels in opposition to the force of the wind on the sails. Some MFDs, like those from B&G, will allow the user to enter a maximum value for leeway and use it with apparent wind direction in calculating lay lines and an approach to the start.

Tiny errors in boat speed and compass measurement will make this impossible, as small paddlewheel and compass errors become substantial errors in calculating the motion of the water.

TRUE WIND / GROUND WIND

Many sailors claim that the apparent wind is all they care about, and that suffices when it comes to setting sails. But to be fully aware of sailboat performance or how the wind is changing, knowing the direction of the true wind as accurately as possible is critical.

As our boats cannot measure the true wind without being anchored to the ground, a calculation relative to the bow is done by our boat instruments using speed through water. From this useful calculation, we can understand the boat’s performance. Small errors in the paddlewheel cause small errors here, hardly noticeable compared to apparent wind angle measurement errors.

The calculation to translate into a compass direction, relative to the water on which the boat is traveling, requires good paddlewheel and compass sensors, since small errors in either become very large calculation errors.

High-end systems like the B&G H5000 offer a calculation relative to the ground that is even more sensitive to paddlewheel and compass errors. This sensitivity is because the calculation is made after first calculating set & drift and applying a variety of additional calibration adjustments, themselves derived from previous paddlewheel and compass-aided observations.

COMPASS BEARING OBSERVATIONS

When Strider’s B&G Precision 9 satellite compass was compared head-to-head with the Furuno SCX20, the two compared very favorably in reporting compass bearing, no matter how much the boat was tossed about, steered quickly, or otherwise. A user would have to go out of their way to find any difference in raw accuracy. However, there was a noticeable exception the day a crew member had moved the dehumidifier into the forward cabin. It was enough to change the heading 10 degrees on the Precision 9, whereas the SCX20 faithfully showed the correct bearing.

A stereo boom box could have the same effect, and as we experienced on a Beneteau 393, the manufacturer’s placement of the magnetic compass near DC power cables resulted in 5 degrees of error on some points of sail, when the refrigerator cycled on.

All in all, in one dimension without installation issues, the B&G Precision 9 was unbeaten.

SET & DRIFT OBSERVATIONS

The SCX20 outshined the B&G Precision 9 when the instruments calculated set & drift. In light wind, or anchored, the SCX20 outshined the Precision 9, in that it enabled the Zeus 3 to more accurately represent the direction and speed of the water. “More accurate” was variable with the intensity of the current, the direction of the current, and the speed of the boat. The 3x precision of the SCX20 roughly provided 3x to 10x increase in calculations here.

However, we took note that the variation in set & drift rapidly disappeared as the wind speed shot past 10 knots.

DIAGNOSTICS

Diving deep into the NMEA-2000 diagnostics screens, we noticed that the SCX20 had considerably less noise when our J/109 was stationed at the dock. The Precisions 9 rate sensors were showing the boat moving back and forth, where as the SCX20 showed a rock-solid heading. Comparing the SCX20 to the compass included with our ZG100 GPS, we could see that the ZG100’s rate-of-change sensors showed tremendous noise.

The SCX20 stands out in another way when paired with a Furuno instrument display. The instrument display shows off its abilities to detect slight differences in the direction and speed of moment at the bow vs. the middle vs. the stern of a vessel. Although a cruiser doesn’t need this level of accuracy, it could be helpful when using bow thrusters to keep a boat precisely oriented relative to a slip when docking. We wonder if there is an untapped potential to determine a sailboat’s leeway under each point of sail, and from that, even more accurately determine set and drift, or to possibly display the amount of leeway to the crew, possibly alerting them to sail trim errors.

A couple of obstacles to doing this include:

• How well the user can align the SCX20 to the boat. As the B&G doesn’t show fractions of a degree in GPS COG or Compass Heading, the user is challenged to get the compass aligned with the hull any better than +/- 0.5 degrees, except to go to a known source of current direction.

• Although, the SCX20 can be finely adjusted when pole mounted, if mounted on the deck both the B&G and Furuno instruments restrict calibration values to whole numbers of degrees, so the failure to mount the compass perfectly on a curved deck, can’t be compensated except in whole numbers.

CONCLUSIONS

If you have a modern MFD, the Furuno’s SCX20 will help it better calculate the forces of wind and water on your boat, and share it with you in an intuitive two-dimensional manner with arrows going to or away from your displayed sailboat icon rather than pointing in a useless manner.

In addition, advanced features like the detection of lifts and headers, an approach to a race start, and the overlayed display of lay lines on electronic charts are no longer subject to compass error. That just leaves you the paddlewheel to keep clean and calibrated, the reward for which is better mastery of your boat in all kinds of wind and water.

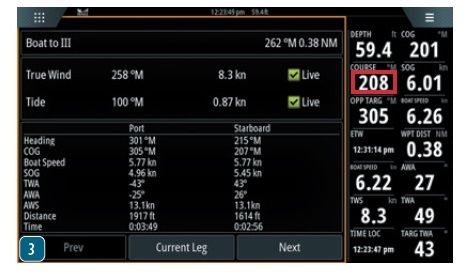

These image pairs (labeled 1 & 2) are from a B&G Zeus 3 MFD with input from the Furuno SCX20 compass. Each pair represents nearly the same moment in a race in different views.

1. The Sailsteer view (left) shows Strider heading 283M degrees on port tack, a .69-knot current (blue arrow), and the need to tack in less than 3 minutes (red box upper right). The chart view (right, enlarged for detail) shows the race mark flag and the boat perpendicular to the next layline (green line).

2. This pair of images, recorded after tacking over to port tack (202 degrees), shows the full chart view, along with the adjacent databoxes.

3. This page view, with boat heading 208 degrees (red box), shows several functions illustrated in the pairs above, but strictly in numerical format.

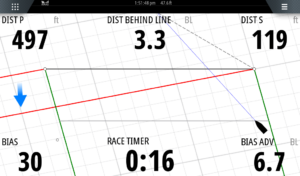

1. In this screen grab, the sailor is pacing to arrive at the start line in 16 seconds. The boat’s sensors aid the MFD in accurately portraying a tidal current (blue arrow), and to help determine that the right side of the line is favored by 6.7-boat-lengths (blue box, lower right). Mark Chisnell details the other features shown in this image (see www.bandg.com/blog/racepanel-series-with-mark-chisnell-part-5-sailsteer/).

2. Four sensitive GPS antenna spaced within inches of each other inside the Furuno compass housing enable it to sense the boat’s heading, just as a compass would, even if the boat is not moving.

3. If your boat isn’t constructed of carbon fiber, metal, or other materials that entirely block GPS signals, you can consider installing the antenna inside your boat. On Strider, the Furuno SCX20 was installed in the V-berth using the rail mount option. The single NMEA-2000 cable runs through the mount.

Don,

As a fellow contributor, I wanted to compliment you on a great article. I always like reading about the “latest and greatest”. My question/concern is about the SCX20’s ‘digital delay’.

Newbies and seasoned sailors are both subject to what aviators call spatial disorientation. We have both been there- no moon, 100% cloud cover and the only thing keeping you orientated is the card on the compass. With the classic compass, there is no delay- you turn the wheel, it spins. Also with a conventional magnetic heading sensor, there is no delay.

However, if one relies on COG calculated through the MFD, or worse a tablet, the delay can result in 360 turns. What is your opinion regarding the delay on the SCX20?

Yes prudent mariners will always have a classic compass at the helm. But some of the new boats are actually deleting the compass.

thanks

Bill

Hi, Thank you Bill for the compliment. When answering let me be careful to differentiate between choosing to display Compass vs. COG on my mast mounted B&G Displays, the B&G H5000 Graphic.

When displaying compass direction, set to zero damping, I experience no delay with either the Precision 9 or the SCX20 as the compass source. They seem to be identically responsive, and far better than my six-inch mechanical ship’s compass.

When displaying COG, set to zero damping, I experience a ton of delay with either my primary GPS the B&G ZG100 and the borrowed SCX20 as the source. They are not identical, the delay is less with the SCX20.

I don’t have any insight why there is a difference.

I agree that the delay in COG can affect the helmsman steering, although not in a circle. I have enough displays where I can put both values up. When a crew chooses to steer by the COG rather than compass, they will frequently oversteer, back and forth before settling on the course they want.

Happy Holidays!

Thank you for a really interesting article. Its great to see a bit under the hood of these new systems

I have a steel ketch with an (old) Raymarine ST autopilot. This does a great job at correcting for compass errors- except for heeling error to which it is blind and is fairly significant when there is 30 tonnes of steel swinging below the mast-mounted sensor. I have tried various sensor positions but the end I always have about a degree of compass error each degree of heel. So, two questions:

1. it looks like the SCX 20 could solve my problem ( assuming it can handle heel without an error), if it integrate into Raymarine’s Sea-Talk. Any thoughts on this?

2. Raymarine offer what seems to be a comparable product in their EV sensor. Can you comment on the comparison between these?

Purchased a B&G Triton 2 system 2 year’s ago. It is the worst piece of marine equipment I’ve ever purchased in my 65+ years of sailing. Multiple tech support calls (8) and the replacement of 4 defective new component’s. Additionally, hold times to tech support varied from 20 minutes (best) to 1 hour and 45 minutes (worst). Plus the varying knowledge of tech support.

Just my experience.

The Triton 2 displays on my boat have been great. I will say that B&G’s support is quite comically ill prepared after the battery died in my WS320 wind instrument they couldn’t sell the battery at all and had to replace the whole unit under warranty to get me a new battery. Hopefully its less abysmal now as that was 2020. I do wish that the chart plotter could update the Triton 2’s over NMEA but thankfully on my install plugging USB into the back isn’t too bad. The displays are great and easy to read in the sun for me.

So it sounds like this might be a good tool for swinging a magnetic compass…

It’s getting harder to find good compass adjusters.