Diesel Crankcase Venting

The recent diesel mechanics’ forum (Feb 1) reminded me of a question I have been trying to get answered. Perhaps you can help.

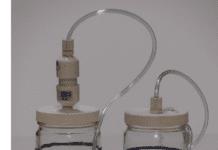

My boat has a 1985 Universal 40 engine. The crankcase breather hose runs down below the engine, venting into the bilge. Although there is not much of a discharge I would prefer that all vapors are directed back into the engine. I have noticed more recent designs connect this hose to the air intake. To accomplish this I have welded a small tube near the inlet end of the air cleaner. I would assume that at that point the negative pressure is not too great.

My air filter is in a canister similar to those used on car engines in the ’60s and ’70s. I have yet to connect the hose to the inlet out of concern that there may be some difference between my engine and the later designs that I am not aware of. Would there be any harm done in venting the crankcase back to the engine air intake?

-Jim Phillips

Via e-mail

We put your question to our diesel answer-man, Mike Muessel of Oldport Marine in Newport, Rhode Island (and of Mailport fame, but possibly not fortune). His response:

I see no problem with venting the crankcase into the air inlet as long as the fitting you added is at right angles to the incoming air flow, allowing natural venting. Any other angle could cause a venturi effect and create a vacuum in the engine base, resulting in excessive oil consumption.

Hopefully the engine is in good condition. High base pressure is caused by worn piston rings, and no amount of venting is going to cure that problem!

———-

Diesel Additives

I was in my local Walmart today when I saw a diesel fuel additive made byPower Service. The claim was that it prevented gelling, cleaned injectors,lubricated pumps and dispersed water. How do you think my Westerbeke would like it?

-Eugene C. Deci

Suttons Bay, MI

Again we defer to Capt. Mike:

There are many types of diesel additives designed to accomplish a variety of chores. First, there is the type that prevents gelling in cold weather. Diesel begins to gel when the weather gets very cold, as my friend the ski-lift mechanic knows all too well: When his ski area lost power on a cold day and the emergency diesel engine refused to start because of fuel gelling, he and his crew were forced to evacuate the lift using bosuns’ chairs.

Another type of additive raises the fuel’s cetane rating. The cetane rating in diesel is similar to the octane rating in gasoline. My marine mechanic buddy in Maine insists on mixing a “cocktail” for many of his clients’ smoky engines. And it works.

A third type helps replace the lubricity lost when sulfur levels were reduced by the government a few years back.

And then we have the water-eating additive to help your engine digest small amounts of moisture.

It sounds like you have an additive that combines all of the above properties into one mixture. Don’t expect any of the above potions to perform miracles like overhauling your worn-out engine-but when they’re used judiciously, they can be very helpful.

———-

Flexible Shaft Couplings

Have you ever done a test on flexible shaft couplings? Are they beneficial and worthwhile? I am considering one for my Beneteau 361. The boat has a 27-hp diesel and an Autoprop. What impact will there be on electrolysis and zinc usage? Does the coupling electrically isolate the shaft from the engine? Is this a good thing? The Autoprop has a small zinc which needs frequent changing even though I’m at a mooring.

-Gary Garson

Via e-mail

No, we haven’t tested flexible shaft couplings, but are familiar with them. Probably the best-known flexible coupling is the Drive Saver, made by Globe Marine Products, a division of Globe Rubber Works in Rockland, Massachusetts (781/871-3700; www.globerubberworks.com).

The purpose of such a coupling is twofold: to reduce vibrations caused by slight misalignment between the engine transmission and propeller shaft coupling, and to electrically isolate the engine from other underwater metals.

The decision whether to electrically isolate the engine is tied in with the concept of bonding, discussed in PS Advisor in the January 15, 2002 issue. Bonding is when all underwater metal parts, such as through-hulls, are connected by wire or other conductor so that their voltage potential (in the electrolyte of seawater) is the same. When no part is more noble or anodic than others, and you’ve installed a few zinc anodes in the right places, like the prop shaft, no wasting of metal material due to corrosion should occur-theoretically.

The other approach is not to bond, but to electrically isolate all under- water parts and put a zinc on each one. (Unfortunately, this is difficult on some parts, such as metal through-hulls, which is one good reason to bond in the first place.)

The Drive Saver electrically isolates the engine and prop shaft from other underwater metals.

The choice is not a simple one, as much depends on the individual boat and its surrounding environment. In some cases, bonding may minimize electrolytic corrosion, and in other cases promote it.

If you think you have a problem, you might consult the American Boat & Yacht Council (ABYC) standards on the subject (E-1), or perhaps discuss it with Yacht Corrosion Consultants/Professional Mariner in Rye, New Hampshire at 603/433-4440; www.pmariner.com.

As for the small zinc on the Autoprop, that’s to protect the prop because it’s made of more than one type of metal-bronze and stainless steel, which have different voltage potentials. The more anodic bronze could start to disappear if the zinc isn’t in place.

Some loss of zinc is to be expected, but if you think it’s disappearing faster than normal, you should check with Autoprop USA in Newport, RI, 401/847-7960.

———-

Twin Forestays

I have a 1986 30-foot Carter fitted with twin forestays and I’ve thought about converting it to a single forestay with roller furling and running the other forestay to a reinforced attachment point on the deck a few feet aft, on which I could hoist a small storm jib. But I don’t think I’ve ever seen a rig where the inner forestay was attached at the masthead-they’re always rigged so that the forestays run parallel. This usually then requires fitting running backstays from the attachment point part way down the mast. Why are the forestays parallel in these rigs? Is it an aesthetic issue or is there some aerodynamic reason?

I haven’t been able to discern any pattern to the spacing between forestays in cutter rigs-sometimes they are very close together, at other times far apart, on similar sized vessels. If spacing is not crucial, it shouldn’t matter if the sail luffs are closer at the head than the foot. I expect Bernoulli is involved here in some fashion. Any observations on this?

-Stan Heshka

New York, New York

We gather from your description of your rig that the two forestays both lead from the masthead to the stem, probably side by side rather than fore and aft of one another. This is a solid cruising rig that enables you to more easily fly two headsails when sailing downwind, and provides a safety backup in case one stay should fail. It does, of course, prevent you from having roller furling unless the two stays are quite far apart and thereby well off centerline.

You could lead one stay to an attachment on deck aft of the stem and leave it attached to the masthead, but you wouldn’t be able to tack the jib or genoa through the slot very easily… and maybe not at all because there probably wont be enough room at the top. Also, if its attachment point at the masthead is off center, loads on it will not be in line with the backstay or other forestay. Thats why an inner forestay usually attaches to the mast, on centerline, at some point below the masthead.

The two stays don’t have to be parallel, and aren’t on all boats, but we guess that parallel stays look better. If you change the angle of a stay you’ll have to have the sail recut, of course.

A boat with a forestay that leads to the stem and also has an inner forestay a few feet aft is called a double-headsail sloop. Generally, only one sail is set at a time. The forestay carries a large genoa for light air. When it’s overpowered, it’s furled and a smaller staysail on the inner forestay is unfurled or hoisted. This, we think, is generally what you’re getting at with your idea for setting up a storm jib, and we see no reason it wouldn’t work, given a couple of requirements: First, make sure the attachment point for the inner forestay on deck is well reinforced belowdecks. It won’t do to simply bolt a padeye or other fitting in the middle of things without a good backing plate. Even then, make sure the deck in that area will be able to take the strain of a tight halyard and a strong wind. Second, you’ll probably want to be able to remove that inner forestay by means of a Highfield (Hifield) lever or other arrangement, so that you can take it aft and stow it on the mast when you don’t need it.

On a cutter the mast is usually located a bit farther aft, more toward the center of the boat, and the forestay may lead to the end of a bowsprit forward of the stem. This provides more separation between the jib and staysail, and certainly a bigger slot through which to tack the jib. With a cutter, both sails are set together in normal conditions; when the wind increases uncomfortably, the jib is struck, the mainsail reefed, and the staysail left in place.

Twin headsails provide a lot of built-in options that make sail handling simpler and safer. But if you want forestays located fore and aft of one another, we’d suggest planning a sufficient slot through which the jib/genoa can be tacked. Walking it through is a pain. The exception would be if the forestay has a large light-air sail and the inner forestay has just a working headsail for most conditions. In this case, the light-air sail can be furled for tacking. You’ll lose a little time, but this set-up would mostly be for offshore sailing anyway, where you might stay on the same tack for days on end.

Good luck with the project.