REDUCING CHAIN TWIST

With regards to responses to your Inside PS blog post on chain twist “How Well Do Swivels Reduce Chain Twist?” as with most aspect of anchoring there is never one right answer. What works for you, or me, does not necessarily work for someone else.

As an example, when an anchor is deployed and tension applied to the rode, the anchor then meets the seabed and, we hope, the anchor engages with the seabed and then sets. Simple stuff. But as a modern anchor engages with the bottom, the toe starts to dig in then the shackle end of the shank also begins to dig in. The toe and the shackle bury roughly at the same rate. This is one reason why most modern anchors feature thin, but strong shanks, because a beefy shank (common in older designs) resists bottom penetration. If you add a swivel to the rode on a modern anchor, it will be the biggest component in the rode, even ‘fatter’ than the anchor shank —and this swivel will detract from anchor performance.

Adding a swivel needs to be considered in combination with the rest of the rode, the chain, anchor, shackle and windlass, not considered in isolation. The best way to remove twists in the chain is to retrieve the anchor until the anchor hangs vertically. Torque in the chain will remove virtually all twists. However, whether your chain is hanging dry in the air or is still in water, the friction between the links will be sufficient to leave at least half a twist in the chain. This half twist may never untwist and your anchor may arrive at the bow roller upside down. This will happen no matter how good your swivel is since the swivel also suffers from friction. Fortunately, the way modern anchors are designed, if one arrives upside down it will often re-orient itself to fit the bow roller. So why have a swivel?

Our Maxwell windlass retrieves quickly, so quickly that there isn’t enough time for the anchor to self-right, and we either need a device that automatically self rights the anchor, or we stop the windlass before the anchor reaches the bow roller and manually right the anchor.

One redeeming feature to twists in the anchor rode—they will not pass through the chain wheel/gypsy.

Jonathan Neeves

Josefina, Lightwave Catamaran

Australia

USCG LEADERSHIP 44

Your review of the U.S. Coast Guard’s Leadership 44 was very nice, but this is the taxpayers’ money and personally, I see no justification for a $1.2M expense over a high quality semi-customized production boat of $400-500K (see “Leadership 44 is Strong, Stiff, and Lightweight,” PS August 2012). A Catalina 440, for example, could meet the specs really well and if not, the builder could add/customize anything necessary.

Nitzan Sneh

GDY-Kids, Contest 43

Boston, MA

KUDOS TO REINCKE MARINE

Regarding your blog post on DIY boatyards (see “The Disappearing Do-it-Yourself Boatyard,” Inside PS), I would like to recommend Reincke Marine Fabrication in Fields Landing, California

(www.rmfhumboldtbay.com). This is a large facility in Humboldt Bay near Eureka. Its big 150-ton lift is a favorite of the local fishermen and used by the Coast Guard. The Reincke crew are definitely welcoming of do-it-yourself sailors folks who have a decent plan—even for long term projects. We’re in the middle of a long project ourselves and are appreciating how super friendly this yard is. Lots of competent help available if you need it—engine work, welding, painting, fiberglass, etc. Awlgrip topsides are a specialty. And, of course, the prices are much more reasonable than the Bay Area.

Max Allen

via PS Online

STERN-TO STORM ANCHORING?

Regarding your recent report on storm anchoring (see “Anchoring Tactics for Sudden Storms,” Practical Sailor, December 2010) what about a discussion or investigation on anchoring from the stern in major storms? I have been creating a Jordan Series Drogue for my ketch for at sea storm survival. The drogue attaches via a very stout rope bridle to two points on the stern and has a very good track record going stern to in hurricane force winds. It’s called “the sailor’s airbag.”

Dan Jordan the aeronautical engineer who developed the Jordan Series Drogue also investigated anchoring from the stern in hurricane and high wind type events. Dan Jordan has posted a very good article on it this topic at his site (www.jordanseriesdrogue.com).

I have not tried it yet, but will be experimenting with my Jordan Drogue attachments points for stern anchoring. The concept is to use a dedicated “boat length” long rope drogue bridle attached at the stern. This bridle and line becomes a long “anchor snubber.” Shackle this long snubber to the anchor chain or anchor rope at the bow and then let out another 2-plus boat lengths of chain and the boat will swing 180 degrees and be stern-to the wind. This lets you use the traditional bow windlass and primary anchors for both the bow and stern.

With this method there is a loop of chain hanging under the boat that might get caught on the bottom in shallow anchorages so additional rigging might be needed to hold the chain under the boat up off the bottom. In very light winds this “long snubber” method is also used to hold the boat at any required angle to the sun to make better use of solar panels. Even my full keel ketch with the mizzen sail up swings on anchor in serious winds and I could see how chaff and stress would be an issue in a big storm. Anchoring from the stern might calm it right down.

Grant Calverly

via PS Online

We did investigate stern-anchoring in high wind conditions and concluded that although stern anchoring damps yawing, there are many downsides to this approach (see “The Science of Stern Anchors,” Practical Sailor April 2023). Bridle lengths for drogues and Jordan Series Drogues are typically 2-3 times the beam of the boat they are attached to. Greater rope lengths lead to single-leg loading and rapid fatigue of the bridle (ropes do not like repeated on-off cycling). Long legs can also lead to tangles. Additionally, a nylon bridle is not recommended for Jordan Series Drogues. It is too chafe-prone and the shock absorption does not help.

When deploying a Jordan Series Drogue, the bridle should be either polyester double-braid, or preferably, Dyneema. Our later experiments, carried out with Dan Jordan’s approval showed this.

We also found that Dyneema can be a good choice for both the chafe leader (covered) and for snubber

bridles for nylon rodes, since Dyneema is more durable and because elasticity is not necessarily desirable in these applications (see “High Tech Anchor Rode,” PS August 2018). For anchoring with all-chain rode, of course, you will want a nylon bridle.

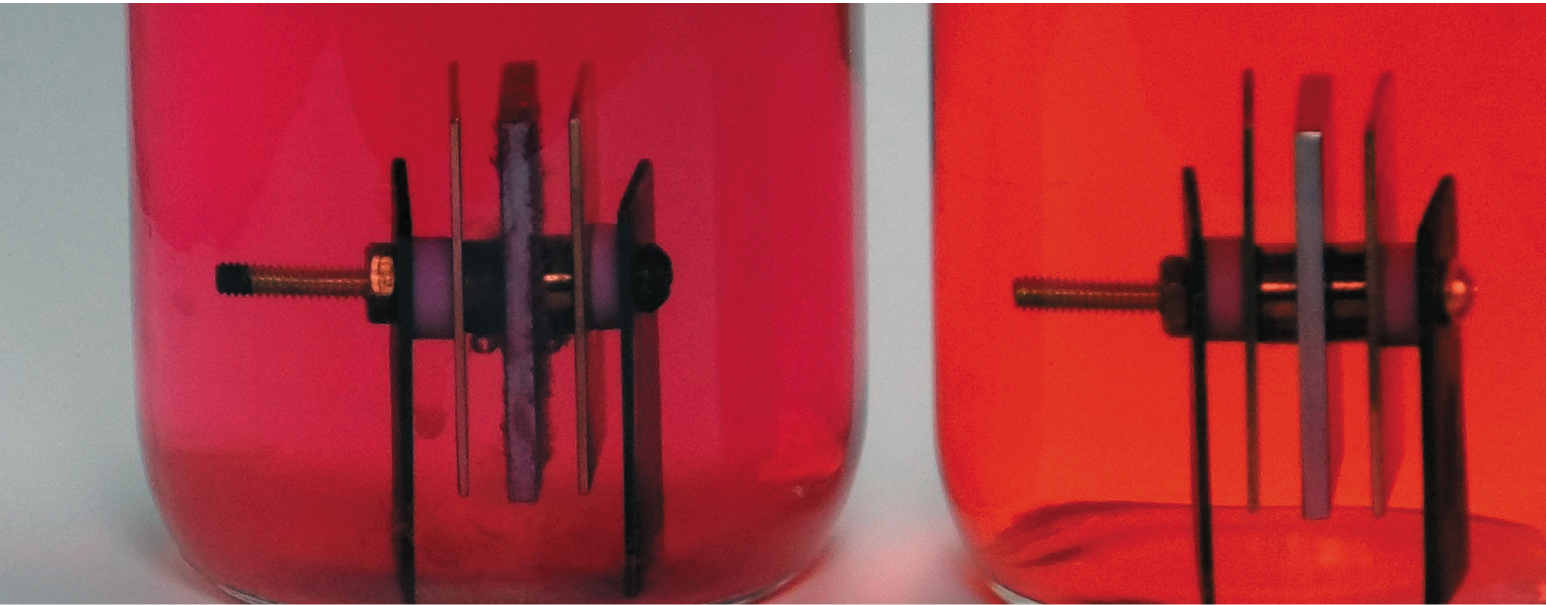

PASTY COOLANT?

I referenced your report on coolants when choosing coolant for my lightly-used Beta 16 diesel engine (see “Coolants Fight Corrosion,” Practical Sailor October 2014). I had some difficulty finding Final Charge NOAT, so I switched to Final Charge Global. I recently removed my thermostat and found thick pink paste. I am wondering if this resulted from unintentionally mixing Final Charge NOAT and Final Charge Global.

Do you know if mixing these two products could result in the pink sludge in my engine?

Bill Grube

via PS Online

It is possible that the silicate level in the Final Charge NOAT was higher than in Final Charge Global. When mixed, the excess silicate precipitated, forming the goo you found. The small amount you found was harmless and the problem should not recur. In general, coolant should be changed every 2 years because of the risk of chloride (salt) contamination from tiny leaks. Check the pH of the coolant. If it is lower than 7, that indicates a problem. Also check chloride while you are at it. A chloride reading over 100 ppm suggests a saltwater leak, another possible cause.

OPEN TRANSOM INSIGHT

Your report on open transom designs (see “Open Transom Pros and Cons,” Practical Sailor May 2023) offered some sensible solutions. I personally don’t care for the open transom. Three offshore round trip voyages to the Virgin Islands from North Carolina. There were no horrible conditions, but some big seas occasionally. I was never pooped. But with an open transom? Maybe.

But another thing not often mentioned is while an open transom can make it easier to get off and on a dinghy, it also makes it easier for unwanted visitors to get on the boat. Over the years, I have read and talked to a couple people who have had intruders swim out to their boats and climb aboard over their open transoms. It’s not a big thing in the scheme of life but something to be aware of. Open transoms can also make installing a self-steering windvane problematic. Choices. Compromises.

John Stone

Far Reach, Cape Dory 36

Beaufort, North Carolina

WORM GEAR STEERING

Regarding your recent discussion about steering (see “Steady at the Helm,” Practical Sailor March 2020), it appears you left out my Edson worm-gear steering system. My problem with the system is that when I am in reverse and get a head of steam going, the force on my large rudder kind of makes it really hard to turn the wheel. I have a Roberts steel 36-footer.

Thomas Reynolds

via PS Online

Worm gear steering systems are rare on recreational sailboats these days and that’s probably why we missed the boat. The design has fallen out of favor because it offers very little feedback to the helmsperson, and compared to other systems, it has a lot of friction. Internal friction caused by years (decades?) of wear, is probably one of the factors affecting your ability to steer in reverse. On the good side, a well-maintained worm gear steering system has very few failure points, making it sluggish, but reliable.

SWAGING INSIGHT

Thanks for the article on the entirely too obscure subject of marine terminal swaging, see (“Swaged Rigging Terminal Failures Raise Concern,” Practical Sailor December 2019). I recently bought all new standing rigging for my boat and during the process had occasion to see two swages with some curvature in the shank. This left me unsettled as to why and whether it foreshadowed problems. So I went off on a tear researching online and was surprised to find the subject poorly covered by the sailing community.

There is plenty written about inspecting old rigging—examining rust spots, cracks, etc.,—and how-to articles on assembling mechanical terminals, but a good discussion on possible defects in new swaging, such as modest variations in swage form (lines, ring patterns, etc.) were rare to say the least. Basically, the average sailor buys these things from their rigger on good faith and the assurance those “very expensive” swaging machines do the magical thing and we should not worry. If in fact you know of some good sources on this topic please spread the word, I’d love to be better educated!

Christopher Codrington

via PS Online

The world recently lost one of the great resources on topics such as this when master rigger Brion Toss, the author of that report, died in 2020. Practical Sailor still has a network of rigging professionals we can count on for guidance and will be following up with them on this and other related topics.

DEHUMIDIFIERS IN CAROLINAS

Regarding your recent blog post on monitoring humidity on board (see “Understanding Dew Point to Prevent Boat Mildew,” Inside PS) it looks like if we have a dehumidifier on board that keeps the interior at about 45 percent humidity, we should be good to go. We purchased a new-to-us boat and there are a few areas with slight surface mildew. We are in North Carolina and it never gets really cold, but a good dehumidifier kept any additional growth in check. Of course once we are away from shore power, the advice noted in your post will be very helpful. Thanks.

Scott Sauve

via PS Online

See this month’s PS Advisor for tips on how you can still use a dehumidifier when you are no longer plugged into shore power.

IMPROVISED ‘CRASH’ PUMP

Regarding your recently republished blog post “Bilge Pump Installation and Maintenance Tips,” I agree that conventional bilge pumps are likely unable to cope with a major hull breach, or even a dropped shaft. If the water ingress cannot be slowed at the source, a life raft might be the best backup if offshore. For power boats, there is yet another emergency option. I have installed commercially made diverter valves at the raw water strainers, with large diameter hoses positioned to pull engine cooling water directly from the bilge. Heaven forbid that I ever need to test the capacity of this arrangement, but I have no doubt that twin 315 hp diesel pumps will beat my three electric bilge pumps.

Mark Laurnen

via PS Online

Enlisting the help of other pumps on board, including the engine’s cooling pump, to clear water in an emergency is a frequently cited strategy. On sailboats, however, the limited flow through the engine’s raw water system is unlikely to save a sinking boat. The highest capacity “emergency pumps” that we’ve tested are belt-driven impeller types from Jabsco that connect to the engine and irrigation pumps that connect to the drive shaft (see “Fast Flow Pump, the Name Says it All,” Practical Sailor August 2010).

CARE WITH BUTYL TAPE

Regarding your report on marine sealants (see “Marine Sealant Adhesion Test,” Practical Sailor December 2016), remember that when discussing butyl you should mention that it shouldn’t be used where it might be exposed to any petroleum product. I’m thinking chain plates where diesel fuel might be stored on deck in jerry cans.

Thomas McCoy

via PS Online

BUILDING A FASTER RUDDER

Do you have any articles on the ideal cross section shape for an outboard rudder mounted 50 mm from the transom vertically? My yacht is a 26-foot trailer sailer that weighs 2.5 tons.

Scott Meyers

via PS Online

The most common choice would be a rudder with NACA 0012 profile (see www.airfoiltools.com/airfoil/details?airfoil=n0012-il). There are many ways to build a rudder, including laminated solid rot-resistant wood and fiber glass covered foam with a metal armature core. For a DIY project, laminated wood is probably the most practical construction.

CORRECTIONS

When wind speed is doubled, the force on the sails goes up by a factor of four. Other information appeared in the print version of our report April 2017 report “Multihull Madness.”

In the June 2023 issue, our sample equation for measuring output gave an obviously erroneous sum in one of the steps. The online version of the report as well as the downloadable PDF for the June 2023 issue of Practical Sailor corrects the error.

You’ve earned some well-deserved fun time on the water, but you want to be safe. To make it easy for you, we’ve gathered some of our most important research and packaged them into ebooks that makes you an instant expert on almost any sailing topic.

SAFETY AT SEA

Our decades of experience testing tethers and harnesses helped guide ground-breaking research into the failure of a safety tether clip during the 2017 Ocean Clipper Round the World Race that lead to the death of crewmember Simon Speirs (at top right). As a result of our findings, the offending tether clip design has been gradually taken off the market. Learn about the ill-fated tether clip and other important findings regarding onboard safety in two ebooks dealing with safety at sea: “Survival at Sea,” and “MOB Prevention and Recovery,” both of which have been recently updated.

STORM READY

You don’t have to live in hurricane-prone area to benefit from our detailed four-volume Hurricane Preparedness Guide (www.practical-sailor.com/product/hurricane-preparedness-guide-complete-series), which describes the gear and techniques that can help you ensure that your anchored, docked, or moored boat is in the best position to survive an extreme weather event.

GALLEY OUTFITTING

For those who need quick-fix dinners that can basically cook themselves while you’re on watch, you’ll find our pressure cooker tests in the December 2010, issue. We looked at energy-saving “slow-food” thermal cookers in the May 2016 and September 2012 issues. Our July 2007 issue is still a great guide for anyone shopping for a galley stove. Two other items we consider cruising-galley staples are the coffeemaker (January 2014) and nesting cookware (April 2009).