Ever since my own brush with a breezy day that turned an afternoon dinghy sail into an arduous struggle to get back to shore, I’ve kept my dinghy stocked with a few essentials.

• Legal requirements. PFDs and a sound making device. Obvious, but also smart. My daughter once ran out of fuel in the dinghy about a mile from the mother ship. I couldn’t hear the whistle, but I heard the dogs barking in reaction to the whistle’s high pitch and was able to pick her up. Also carry the required lights after dark and a flashlight.

• Oars. Test these out so that you fully understand just how poorly inflatables row, how bad the folding oars are, and whether the oarlocks work at all. If there are two of you, one person paddling on each side often works best. If alone, row from the front with a pulling motion, or scull if you know how.

• Anchor and rode. The rode can be thin, but it should function up to the maximum depth the main boat is likely to anchor in, allowing at least 5:1 scope. This can be a lifesaver if you have engine trouble.

• Radio. A handheld VHF is sufficient, since you should be within range of the mother ship and other sailors. A cell phone in a dry box is also smart.

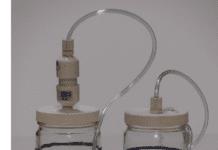

• Tools and spares. A good minimum is a copy of paperwork, shear pins, screw driver, gas filter, locking pliers, and a spark plug with wrench. Keep these in a small dry box or drybag.

• Drinking water. At least a 1-liter bottle per person.

REMOTE AREAS

Launching a tender should not be taken lightly. If the motor sputters or fails, stay close to shore until reaching a place where the course to the mother ship is downwind and down-current, or nearly so. If it’s not going well, anchor before it gets worse. That buys you time to think, rest, and summon help.

• Spare gas. At the very least, check the tank every time and go no farther than the distance you are sure you have fuel for. It’s easy to go far on 1/3 tank, only to realize that the return trip will require more fuel, bashing into waves on the uphill leg. Never assume there is plenty left after the last trip.

• Long anchor rode and anchor. A pivoting fluke-type will work, but a small version of an anchor you would use on your boat, such as a Mantus Dinghy Anchor or 4-pound Lewmar Claw are better. It needs to be able to catch the bottom. The first 50 feet of the rode should be a durable working diameter of at least 5/16-inch, but the next 100 feet or more can be polyester bull line or something else light. Keep it on a spool or well-coiled in a figure 8 or over-under coil, ready to go.

• Ditch bag. Take this with you anytime missing the main boat could be dire.

– Water. Several bottles each.

– PLB or EPIRB

– Signaling gear. Electronic flare or bright flashlight. Smoke.

– More tools. But realistically, there’s not that much you are likely to fix in a dinghy.

• Clothing. Cold water kills, even in the summer. If crossing open water, dress for the water temperature, not the air temperature. A dry suit makes sense in some climates. You’ll also need protection against sun.

Stranding in a human propelled craft such as a kayak is less likely, but be realistic about your paddling limits. Practice with your dinghy or kayak in a safe location, and never push new limits in open water. A short trip can quickly get complicated. Be ready if it does.